Candida can be implicated in the pathology of chronic periodontitis.

AimsTo analyze the oral Candida carriage in patients suffering from chronic periodontitis (CP) and its correlation with the severity of this condition.

MethodsMicrobiological samples were taken from 155 patients using the oral rinse (OR) technique and by using paper points in the periodontal pockets (GPP). These patients were divided into 3 groups: 89 patients without CP (control), 47 with moderate CP, and 19 with severe CP. Samples were cultured in a Candida chromogenic agar for Candida. Species were identified by microbiological and molecular methods.

ResultsCandida was isolated in the OR of 45 (50.6%), 21 (44.7%), and 11 (57.9%) patients, respectively, and in the GPP of 32 (36%), 14 (29.2%), and 10 (42.6%) patients from the control, moderate CP and severe CP groups, respectively. Candida was isolated more frequently and in a greater burden in OR than in GPP (p<0.01). Candida albicans was the most prevalent species. GPP of patients with CP had poor fungal biodiversity (p<0.01).

ConclusionsColonization by Candida was present in the samples of patients without CP, and with both moderate and severe CP. Nonetheless, patients with severe CP had a higher rate of Candida colonization, especially by C. albicans.

Candida puede estar implicada en la patogenia de la enfermedad periodontal crónica.

ObjetivosAnalizar la colonización oral por Candida en pacientes con enfermedad periodontal (EP) crónica y su asociación con la gravedad de esta entidad clínica.

MétodosSe tomaron muestras microbiológicas de 155 pacientes mediante enjuagues orales e introduciendo una punta de papel estéril en la bolsa periodontal. Se dividieron los pacientes en tres grupos: 89 pacientes sin EP (control), 47 con EP moderada y 19 con EP grave. Las muestras se cultivaron en un agar cromógeno para Candida y las especies se identificaron mediante métodos microbiológicos tradicionales y moleculares.

ResultadosSe aisló Candida en los enjuagues de 45 (50,6%), 21 (44,7%) y 11 (57,9%) pacientes y en las puntas de papel de 32 (36%), 14 (29,2%) y 10 (42,6%) pacientes de los grupos control, con EP moderada y con EP grave, respectivamente. Candida se aisló con mayor frecuencia y mayor carga fúngica en las muestras de los enjuagues que en las de las puntas de papel (p < 0,01). Candida albicans fue la especie más prevalente. Las muestras de la bolsa periodontal de los pacientes con EP presentaron una baja biodiversidad fúngica (p¿0,01).

ConclusionesHubo colonización por Candida en las muestras de pacientes sin EP y con EP tanto moderada como leve. No obstante, los pacientes con EP grave presentaron una mayor colonización por Candida, especialmente por C. albicans.

Chronic periodontitis (CP) is a frequent inflammatory process of the periodontal connective tissue associated with an insertion loss of the periodontal ligament and the reabsorption of the alveolar bone.22,42 CP is diagnosed clinically by assessing the clinical attachment loss (CAL) and the presence of periodontal pockets.1 CP can lead to tooth loss and is a risk factor for the development of systemic diseases.14 CP may be localized or generalized and is more common in adults.16 In Spain, severe CP is present in 31.5% of the people over 65 years of age.3 Although some key periodontopathogens have been identified, CP occurs due to a complex interaction between the subgingival microbiota (aerobic and anaerobic bacteria and yeasts), the host susceptibility and environmental factors.8,18,22

Candida is an opportunistic pathogen that can colonize and infect the oral cavity,41 especially in patients with facilitating local and systemic factors1,23,28,39 such as the presence of periodontal pockets in CP, oral niches that favour Candida colonization and multiplication.2,18

Sardi et al.11 suggest the potential implication of Candida in the inflammatory and destructive process in the CP. Oral Candida albicans has been isolated in 5–47% of the patients with CP, although its exact role in this disease is yet unknown.5,9,10,18,33,35,44

Considering that in Spain studies on the possible participation and association of Candida with the CP are lacking, the main objective of this study has been to analyze the oral Candida carriage in adult patients with CP in our environment and its correlation with the severity of this important oral disease.

Patients and methodsPatientsThis prospective observational analytical study randomly recruited 155 patients that attended a check-up or review appointment at the Dental Clinic Service of the University of the Basque Country (Spain). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the UPV/EHU (CEISH/23/2010). Study sample consisted of 70 females (45.2%) and 85 males (54.8%) with a mean age of 48.2 years (age range between 30 and 81 years). A minimum age of 30 years was required to be included in the study. Those patients undergoing treatment with antimicrobial agents, immunosuppressant drugs or chemotherapy during the previous month were excluded, as well as patients with loss of more than 10 teeth or presenting oral candidiasis or other oral soft tissue conditions, suffering from a chronic uncontrolled disease (diabetes, hypothyroidism, etc.), immunodeficiencies, or, in the case of the female patients, being pregnant. A medical history and a complete periodontal examination with a graded periodontal probe (PCP-UNC 15 Hu Friedy Mfg. Co., Frankfurt, Germany) were performed in all cases.

Patients were classified according to the diagnosis and severity of CP based on the clinical periodontal index for treatment needs (CPITN: community index for periodontal treatment needs) proposed by the World Health Organization and the CAL index (Clinical Attachment Loss, distance in mm from the cementoenamel junction to the bottom of the periodontal pocket, in 30% of the teeth) of the American Academy of Periodontology.16,39,42 Based on these indexes, the patients were classified in the following three groups:

A) Control group (CG) with 89 patients without CP, 43 females (48.3%) and 46 males (51.7%), a mean age of 43.9 years (range 30–78 years), and with a CPITN <3 and a CAL <1.

B) Moderate CP group (MCP) with 47 patients, 20 females (42.6%) and 27 males (57.4%), a mean age of 53.5 years (range 30–81 years), and a CPITN=3 and/or a CAL between 2 and 5.

C) Severe CP group (SCP) with 19 patients, 7 females (36.8%) and 12 males (63.2%), with a mean age of 55 years (range 33–77 years), and a CPITN of 4 and/or a CAL >5.

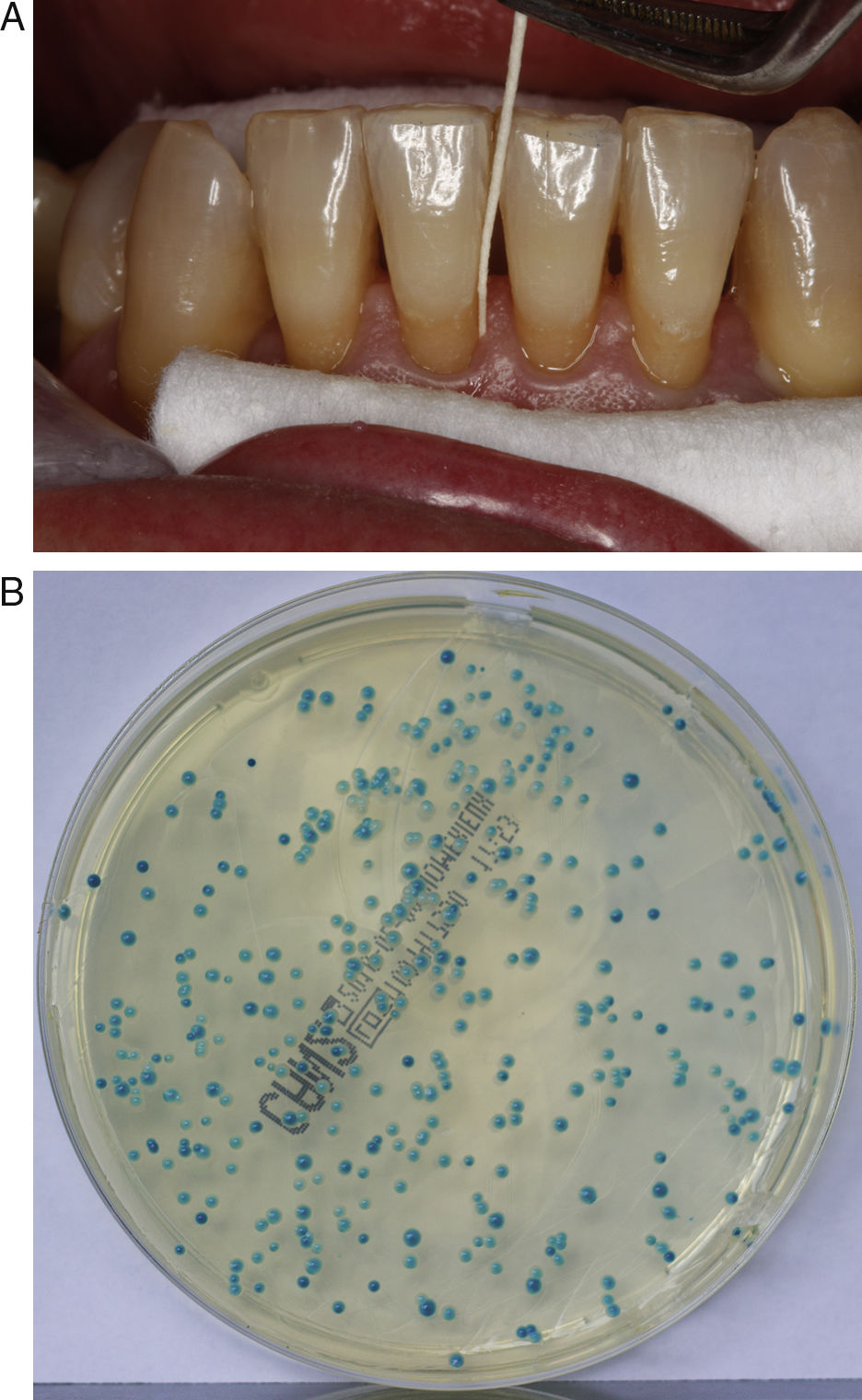

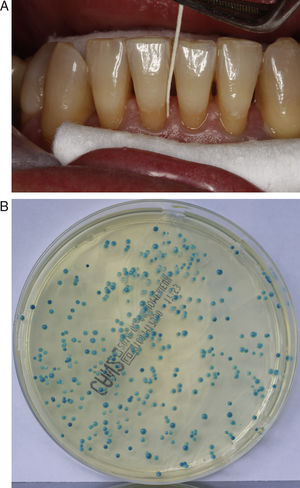

Clinical specimensTwo oral samples were gathered for the microbiological study, a general sample of the oral cavity obtained through a thorough oral rinse (OR) with 25ml of distilled and sterilized water for one minute and placed in 50ml polystyrene tubes,4,44,47 and a periodontal pocket sample (gingival paper point: GPP) obtained with a sterile paper point introduced in the gingival sulcus for ten seconds, after previously securing relative isolation and drying the tooth. The GPP was then deposited in a tube containing 2.5ml of sterile distilled water2,5,35,44 (Fig. 1A). GPPs were taken from the deepest probing depths of the first, third and fifth sextant.19

Culture, isolation and identification of CandidaAfter centrifugation at 4000rpm for 10min, 100μl of the sediment of the OR or 50μl of the GPP were cultured on ChromID Candida chromogenic agar plates (bioMérieux, Marcy L’Étoile, France) and incubated at 36±1 C. The growth after 24, 48 and 72h was recorded by counting the number of colony forming units (CFUs) and by studying the morphological characteristics of the colonies (colour, shape and texture) in order to give a presumptive identification of the species of Candida present4,13,32 (Fig. 1B). Negative growth was considered after ten days of incubation, when the cultures were discarded.

The yeasts were identified with the API ID 32C (bioMérieux) that performs the analysis by doing biochemical and physiological tests. The final differentiation between C. albicans and Candida dubliniensis, observed in ChromID Candida agar as blue colonies, was performed through a conventional multi-detection PCR by amplifying the hwp1 gene that differentiates C. albicans, C. dubliniensis and Candida africana.4,26,36

Statistical analysisThe data were analyzed with a statistical software (SPSS 15.0 for Windows, SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). For the continuous variables, the normal distribution was measured with the Kolmogórov–Smirnov test (all study variables had a non-normal distribution, p¿0.05). The mean differences were analyzed with the U Mann–Whitney (gender; colonization; PIP; sample type) and Kruskal–Wallis tests (groups; fungal species; CPITN index). The categorical variables were compared using the Fisher's exact test. Significance was considered when p<0.05. The biodiversity of the yeast species in the samples was calculated with the Simpson's diversity index.17,44

ResultsGender distribution showed no differences among the studied groups of patients; however, differences were observed in relation to the mean age, lower in the control group (p<0.01).

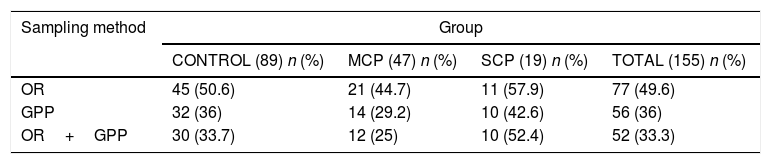

Candida was isolated in half of the samples obtained by OR and in one-third of those obtained by GPP (p<0.01) (Table 1). This was similar among the three groups, being slightly higher in patients from the SCP group (p=0.065) (Table 1).

Positive Candida colonization according to the groups and the sampling method.

| Sampling method | Group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CONTROL (89) n (%) | MCP (47) n (%) | SCP (19) n (%) | TOTAL (155) n (%) | |

| OR | 45 (50.6) | 21 (44.7) | 11 (57.9) | 77 (49.6) |

| GPP | 32 (36) | 14 (29.2) | 10 (42.6) | 56 (36) |

| OR+GPP | 30 (33.7) | 12 (25) | 10 (52.4) | 52 (33.3) |

MCP=moderate chronic periodontitis, SCP=severe chronic periodontitis, OR=oral rinse, GPP=gingival paper point.

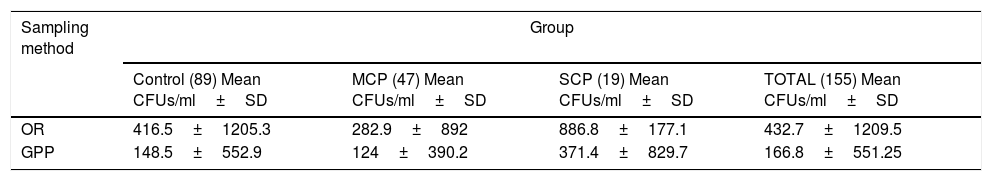

The mean CFU obtained with the OR was significantly higher than that with the GPP (p<0.01) (Table 2). The SCP group had a higher mean of Candida CFU, although statistically non-significant, than the other two groups of study (p=0.3) (Table 2).

Mean CFUs/ml for each group of study and sampling method.

| Sampling method | Group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (89) Mean CFUs/ml±SD | MCP (47) Mean CFUs/ml±SD | SCP (19) Mean CFUs/ml±SD | TOTAL (155) Mean CFUs/ml±SD | |

| OR | 416.5±1205.3 | 282.9±892 | 886.8±177.1 | 432.7±1209.5 |

| GPP | 148.5±552.9 | 124±390.2 | 371.4±829.7 | 166.8±551.25 |

MCP=moderate chronic periodontitis, SCP=severe chronic periodontitis, OR=oral rinse, GPP=gingival paper point.

C. albicans was isolated both in pure culture and in mixed cultures from the OR with Candida parapsilosis, Candida lipolytica, Candida glabrata, Candida krusei, Candida tropicalis and Candida colicullosa. Furthermore, other nine Candida species were isolated in pure cultures in the OR, the most significant being C. parapsilosis and C. dubliniensis. Other fungal genera were also isolated but in a lower frequency (Tables 3 and 4).

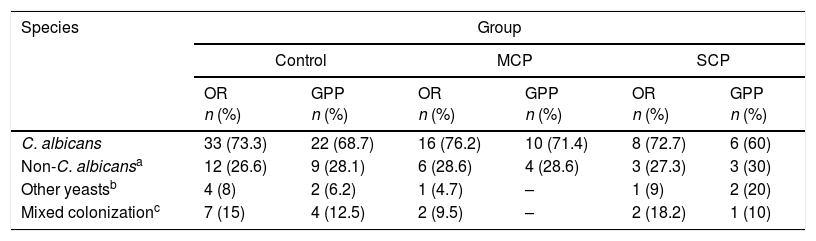

Fungal species according to patients’ group and sampling method.

| Species | Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | MCP | SCP | ||||

| OR n (%) | GPP n (%) | OR n (%) | GPP n (%) | OR n (%) | GPP n (%) | |

| C. albicans | 33 (73.3) | 22 (68.7) | 16 (76.2) | 10 (71.4) | 8 (72.7) | 6 (60) |

| Non-C. albicansa | 12 (26.6) | 9 (28.1) | 6 (28.6) | 4 (28.6) | 3 (27.3) | 3 (30) |

| Other yeastsb | 4 (8) | 2 (6.2) | 1 (4.7) | – | 1 (9) | 2 (20) |

| Mixed colonizationc | 7 (15) | 4 (12.5) | 2 (9.5) | – | 2 (18.2) | 1 (10) |

MCP=moderate chronic periodontitis, SCP=severe chronic periodontitis, OR=oral rinse, GPP=gingival paper point.

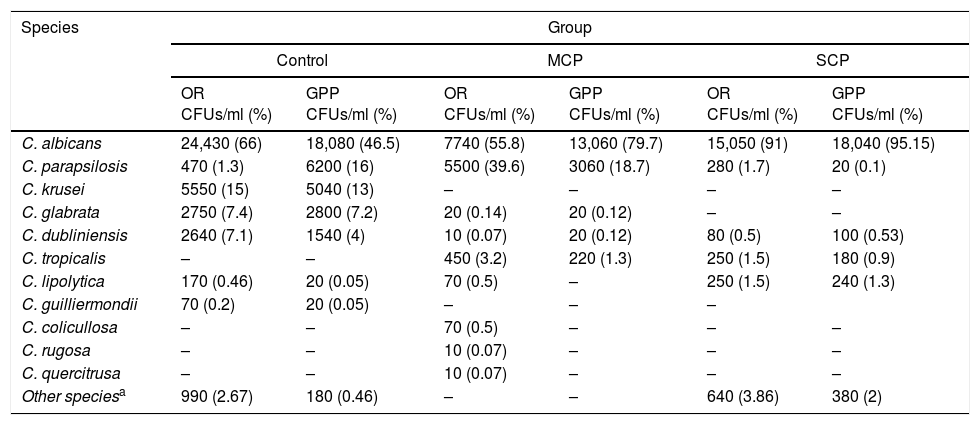

Number of CFUs/ml isolated according to species, patients’ group and sampling method.

| Species | Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | MCP | SCP | ||||

| OR CFUs/ml (%) | GPP CFUs/ml (%) | OR CFUs/ml (%) | GPP CFUs/ml (%) | OR CFUs/ml (%) | GPP CFUs/ml (%) | |

| C. albicans | 24,430 (66) | 18,080 (46.5) | 7740 (55.8) | 13,060 (79.7) | 15,050 (91) | 18,040 (95.15) |

| C. parapsilosis | 470 (1.3) | 6200 (16) | 5500 (39.6) | 3060 (18.7) | 280 (1.7) | 20 (0.1) |

| C. krusei | 5550 (15) | 5040 (13) | – | – | – | – |

| C. glabrata | 2750 (7.4) | 2800 (7.2) | 20 (0.14) | 20 (0.12) | – | – |

| C. dubliniensis | 2640 (7.1) | 1540 (4) | 10 (0.07) | 20 (0.12) | 80 (0.5) | 100 (0.53) |

| C. tropicalis | – | – | 450 (3.2) | 220 (1.3) | 250 (1.5) | 180 (0.9) |

| C. lipolytica | 170 (0.46) | 20 (0.05) | 70 (0.5) | – | 250 (1.5) | 240 (1.3) |

| C. guilliermondii | 70 (0.2) | 20 (0.05) | – | – | – | |

| C. colicullosa | – | – | 70 (0.5) | – | – | – |

| C. rugosa | – | – | 10 (0.07) | – | – | – |

| C. quercitrusa | – | – | 10 (0.07) | – | – | – |

| Other speciesa | 990 (2.67) | 180 (0.46) | – | – | 640 (3.86) | 380 (2) |

MCP=moderate chronic periodontitis, SCP=severe chronic periodontitis, OR=oral rinse, GPP=gingival paper point.

C. albicans was isolated from GPP in 67.8% of the patients with positive cultures, being 8.9% of the latter mixed cultures (Table 3). The species isolated with C. albicans were C. parapsilosis, C. lipolytica, C. glabrata, Candida famata and C. tropicalis. Also, seven other Candida species and six other fungal species were isolated from the GPP (Tables 3 and 4).

The Simpson's biodiversity index scored 0.53 for CG, 0.55 for MCP and 0.17 for SCP in OR samples and 0.72 for CG, 0.33 for MCP and 0.094 for SCP in GPP samples (p¿0.01).

DiscussionThe relationship between Candida colonization and CP is controversial, although a high burden of yeasts in the periodontal pockets is considered a factor that worsens the disease.24,29 In our study CP patients showed a higher Candida colonization than patients without CP. Colonization was observed in more than half of our patients with deep pockets (SCP), compared to the 26.4% of the patients reported by Barros et al.2 In addition, only the periodontal pockets were colonized in several patients, justifying taking general (OR) and specific (GPP) oral samples to assess the implication of Candida in CP.14,27 According to other studies,2,44Candida was more frequently isolated in OR than in GPP, differing from the observations of McManus et al.24 Moreover, the entire sample of our patients showed a higher colonization than Urzua et al.,44 with higher percentages of colonization in the SCP group although the differences were not significant, in contrast with the study of McManus et al.24 This might correlate with the different populations of the study, where control patients may show a lower colonization by Candida. Furthermore, the group distribution and the methodology are different, resulting in a complex comparative analysis. In the same line, we observed high percentages of colonization of the periodontal pockets, especially in the SCP group. Other studies2,5,12 have shown very variable percentages (3–47%) of colonization of the periodontal pockets in patients with SCP.

We were unable to confirm a statistically significant relation between the colonization of Candida and the severity of CP, described by Canabarro et al.,5 or its use as a predictor of the severity of CP. Nonetheless, based on the number of CFU, the severity of CP correlated with a heavier fungal burden and, as described by Urzua et al.,44 the number of CFU/ml in samples of patients with SCP was higher. However, the number of CFU in the periodontal pockets was lower than in the OR, in contrast with the results described by Barros et al.2 and McManus et al.24

In our study, 19 different fungal species were isolated, with a lower biodiversity in SCP group, in agreement with Urzua et al.,44 but disagreeing with Canabarro et al.5 that observed a higher variety of species in deep periodontal pockets. Nonetheless, other studies, such as those of Krom et al.21 and Cho et al.8 describe a decrease in the microbial diversity in the established disease. This lower diversity of fungal species in SCP might be due to selection and persistence of better adapted species to the oral niche such as C. albicans, a species that was isolated particularly in patients with CP, showing similar results to other studies.2,19 The non-C. albicans species of Candida most frequently isolated were C. parapsilosis and C. dubliniensis, corresponding to what has been described in other similar studies.19,44

Jewtuchowicz et al.19 and McManus et al.24 described C. dubliniensis in patients with CP. However, in our study, C. dubliniensis was more frequent in the CG than in CP group.

The presence of C. parapsilosis in the periodontal pockets of our patients with CP differs from a study performed in Argentina by Jewtuchowicz et al.19 We consider that these differences might be related to geographical differences, as the different aetiology of some fungal infections have been recognized according to the geographic location and the infectious niche.20,21 Furthermore, we consider of importance to emphasize on the isolation of C. glabrata and C. krusei in these patients as they are acknowledged emergent oral pathogens resistant to fluconazole and other antifungal drugs.20,30,31

Without a doubt, C. albicans is the species with the highest pathogenic potential due to its different properties and virulence factors that allow them to remain in periodontal pockets and to resist its elimination through hygiene.6,43,46 Several authors23,37,45 have observed hyphae on the border of the sulcular epithelium and in the subepithelial connective tissue which favour the adhesion and the tissue invasion, as well as the coaggregation with other microbial species and the progression of the CP. This coaggregation with some bacteria may act as a barrier and hinder the access of the antimicrobial molecules or even the immunoglobulins present in the oral cavity and might reduce or block the therapeutic action of the antibiotics.11,27 The ability of C. albicans to grow in aerobic and anaerobic environments enables its adaptation to the microenvironment of the periodontal pocket and the crevicular fluid.

The ability of C. albicans to coaggregate with bacteria forming mixed biofilms and enhancing adhesion,6,23,40,45,46 as occurs in supra and subgingival dental plaque,38–40 stands out among the characteristics that make C. albicans an active participant of the inflammatory and destructive process of chronic periodontal disease.39 Symbiosis, antagonism and commensalism among the different microorganisms of the dental plaque are phenomena observed in CP,15,25,28 particularly between Candida and some anaerobic bacteria (Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella intermedia and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans), crucial in the evolution of this disease.37

Candida has the ability to adapt to different niches of the oral cavity by expressing different phenotypes and virulence factors in relation to the pH, presence of oxygen or polysaccharides, etc.39,40Candida secretes different proteinases that release toxic or antigenic agents that can perpetuate tissue inflammation and activate the immunologic response,2,15,18,40 similarly to what happens with certain proteases of P. gingivalis considered crucial in the pathogenesis of CP.18Candida is also capable of secreting phospholipases that facilitate its adhesion to tissues and degrade cellular membranes enabling cytolysis.38–41

Scaling and root planning, together with a correct plaque control with good oral hygiene, is the standard treatment for CP.38,43 Nonetheless, some patients do not respond to this conventional treatment and must take more aggressive therapies, such as broad spectrum antibiotics, that can favour a superinfection by Candida, thus worsening the CP.38–41 This situation may be aggravated if there is a previous oral colonization by Candida. This circumstance may be an important reason to assess the presence of Candida in the mouth of patients diagnosed with CP, especially in those severe and/or recalcitrant-to-standard treatment cases, in order to include antifungal drugs in their therapeutic protocol of CP if there is an active yeast growth.38 Nowadays, there are several contributing therapies for CP such as laser and photodynamic application or toothpastes containing antifungal drugs that may eliminate Candida7,42–44 or probiotic therapies that prevent fungal overgrowth.34

ConclusionsHalf of our patients with CP were colonized by Candida, being more frequent and more numerous in the general oral colonization than in the periodontal pockets. Although we were unable to determine a direct relation between the presence of Candida and the severity of CP, our results indicate that the patients with severe disease show colonization by Candida more frequently and in a higher quantity. C. albicans is the most common species in these patients and is recognized as the most pathogenic, showing some properties and virulence factors that make it the candidate to play a role in pathogenesis, progression and maintenance of CP lesions. The frequent fungal colonization of the periodontal pockets justifies the need to consider it in the therapeutic protocol of these patients.

Conflict of interestIn the past 5 years, Elena Eraso has received grant support from Astellas Pharma, and Pfizer SLU. Guillermo Quindós has received grant support from Astellas Pharma, Gilead Sciences, Pfizer SLU, Merck Sharp and Dohme, and Scynexis. He has been an advisor/consultant to Merck Sharp and Dohme, and has been paid for talks on behalf of Abbvie, Astellas Pharma, Esteve Hospital, Gilead Sciences, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Pfizer SLU, and Scynexis. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Cristina Marcos-Arias is recipient of a grant from Fundación ONCE («Oportunidad al Talento»). Elena Eraso and Guillermo Quindós have received grant support from Consejería de Educación, Universidades e Investigación (GIC15 IT-990-16) of Gobierno Vasco-Eusko Jaurlaritza, Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (FIS PI11/00203), and UPV/EHU (UFI 11/25). Xabier Marichalar-Mendia, Amelia Acha-Sagredo and Jose Manuel Aguirre-Urizar are supported by a grant from Research Groups from the Government of the Basque Country (IT-809-13).