The school must be a safe space that guarantees the inclusion of sexual diversity. Teachers, as well as other possible educational sources, play a key role in this issue. The present study aims to explore the role of the school and other educational agents in the well-being of trans children and adolescents. To this end, 22 life stories written by mothers and fathers of girls and boys who had undergone social transition have been collected and a qualitative analysis has been carried out using MAXQDA software as a tool. For this purpose, three key periods have been considered in the stories: before, during and after having made the transition. Among other aspects, the stories include and value the support that is given to the children by the school, highlighting the role that the families attribute to the teachers as guarantors of their children's wellbeing at school and as facilitators of the transition. The lack of knowledge of child and adolescent transsexuality and the lack of teacher training in this regard, emerge as the main difficulties that these families encounter in the school environment. The role of the peer group and other non-formal contexts such as extracurricular activities are also highlighted as spaces of safety, support and acceptance being cases of rejection and bullying, an exception. The stories show that when the social transition takes place at an earlier age, the rejection and distress at school is lower.

La escuela debe ser un espacio seguro que garantice la inclusión de la diversidad sexual. El profesorado, así como otros posibles agentes educativos, tiene un papel clave en esta cuestión. El presente estudio tiene por objetivo explorar el papel de la escuela y otros agentes educativos en el bienestar del alumnado transexual. A tal fin se han recabado 22 relatos de vida escritos por madres y padres de chicas y chicos que habían realizado el tránsito social, de los que se ha llevado a cabo un análisis cualitativo usando como herramienta el software MAXQDA. Para ello, se han considerado tres periodos clave en los relatos: antes, durante y después de haber realizado el tránsito. Entre otros aspectos, los relatos recogen y valoran el acompañamiento que, desde la institución escolar se da a los menores, destacando el papel que las familias atribuyen al profesorado como garante del bienestar en la escuela de sus hijas e hijos y como agente facilitador del tránsito. El desconocimiento de la transexualidad infantil y juvenil y la falta de formación del profesorado al respecto, emergen como las principales dificultades con las que estas familias se encuentran en el ámbito escolar. Se destaca también el papel del grupo de iguales y otros contextos no formales como las actividades extraescolares que aportan, en la mayoría de casos, seguridad, apoyo y aceptación, y de forma excepcional rechazo y acoso. Los relatos muestran que, cuando el tránsito social se realiza en edades tempranas, el rechazo y sufrimiento es menor.

Transsexuality is a phenomenon present in all cultures and historical moments. However, until a few years ago, it seemed to be something that emerged in adult life without anyone asking what happened during childhood. Of course, it is not that there was no transgender childhood, but that there was no capacity to think about it (Mayor, 2018). In Spain, it will not be until 2013, with the appearance of the first associations of families of transgender minors, when this reality begins to be known and made visible, which opens the possibility of it being observed and studied (Gavilán, 2018). However, although knowledge about transsexuality has increased exponentially in recent years, its study remains scarce (Etxebarria-Perez-de-Nanclares et al., 2023; Fernández et al., 2018), making it necessary to advance in the understanding of these realities in order to, among other issues, be able to accompany them.

Many and varied facts of diversity are currently emerging and becoming visible around the experience and expression of one's sexual identity, both when the sexual identity does not coincide with the sex assigned at birth and when the sexual expression, also called gender expression, does not fit in with the expectations and impositions of gender; these experiences can also lead to a questioning of the dominant gender paradigm and a political positioning. From different theoretical frameworks, from activist positions and from the protagonists of these experiences, different ways of naming these realities are being proposed: transsexuality, transgender, gender nonconformity, gender diverse, gender fluid, non-binary, queer… The formula trans or trans* has been proposed as an umbrella term to encompass all of them (Coll-Planas & Missé, 2015) and thus be able to make a common front against the marginalization and harassment they face, and in defense of their rights. It is therefore of crucial importance to understand the specificities of the different realities being referred to, as their needs may be different.

This study uses the term transsexuality to refer to the condition whereby the sexual identity of a person does not correspond to the sex assigned at birth according to their genitals (Landarroitajauregui, 2018), and focuses on the experiences and needs of those girls and boys who at some point in their life process categorically state "I am a boy" or "I am a girl", not being the sex assigned at birth, and who have made the social transition to live according to their sexual identity. In this way, the girls, boys and young people who are the object of this research are distinguished from those who show non-normative gender behaviors, consider themselves non-binary or manifest other facts of sexual diversity, in order to be able to observe and know the particularities of this population.

Currently, there are two approaches from which to address child transsexuality. The first recommends watchful waiting during childhood (López, 2018), based on the supposedly high rate of desistance that occurs at puberty, and referring to percentages of between 80% and 95% (Esteva et al., 2015). The validity of these data has already been discarded (Ashley, 2022; Mayor & Beranuy, 2017), as confirmed by the first longitudinal study on minors who have made the transition, which shows that only 2.5% have detransitioned (Olson et al., 2022).

In the face of this approach, a model of accompaniment called the affirmative model emerges, which promotes that families listen to and affirm the sexual identity expressed by the child and attend to his or her needs, exploring and supporting a process of transition from living socially according to the sex assigned at birth to living according to one's own sexual identity, which may involve a change of name, pronouns, grammatical gender, manner of presentation, hairstyle, clothing, and the express recognition of their sexual identity by their environment (Ehrensaft et al., 2019; Rae et al., 2019). Such transit is a process that is mainly carried out by the environment and that is, above all, a transit in the gaze, in the perception that others have, and that entails ceasing to see the girl she was supposed to be to, progressively, move on to see the boy she expresses she is, or vice versa (Mayor, 2018).

Until just a decade ago, social transitions in childhood have not only been uncommon, but have rarely been understood, supported or studied, so the data we have on it are still scarce (Ehrensaft, 2017). However, there is already evidence based on clinical observations and accounts from mothers and fathers that point to an improvement in the quality of life of children who transition (Ehrensaft et al., 2019; Mayor, 2020; Sherer, 2016), and that show the positive consequences of acceptance and support from families on the mental health of transgender children (Kuvalanka et al., 2014; Travers et al., 2012). Specifically, in a study with a sample of 73 children aged 3 to 12 years who had made the transition, Olson et al. (2016) find that these children present normative levels of depression and only marginally elevated levels of anxiety, concluding that making the transition has a positive impact on their mental health.

The school should be a safe space where students can freely express their identity and where respect for sexual diversity is promoted (López et al., 2022). However, in the educational context there are constant signs of exclusion towards transgender boys and girls (Dugan et al., 2012) and such discrimination does not only come from the students, but the institution itself, teachers and families that make up the educational community contribute, directly or indirectly, in its perpetration (Aventín, 2015). According to the 2021 National School Climate Survey conducted in the United States on LGBTQ youth experiences by Kosciw et al. (2022), when LGBTQ students report harassment to school, 60.3% of the time they are told to ignore the situation. This persistent discrimination highlights the need to ensure that teachers and educational institutions pay adequate attention to sexual diversity in general and to the situation of transgender students in particular (Kattari et al., 2018). Similarly, in Spain, as indicated by the "2020 Report" of the State Federation of Lesbians, Gays, Trans and Bisexuals (FELGTB, 2020), despite the growing normative and regulatory development, institutions still present many limitations and obstacles to adequately address and accompany during the transition. These aspects could be improved thanks to the action strategies proposed by the European Commission (2022), among which the importance of the existence of a curriculum that includes inclusion and free gender expression is emphasized, as well as the need to have teachers with knowledge about LGBT + issues in each educational center.

In Spain, 70.6% of the autonomous communities include specific legislation on the transgender population and/or LGTBI legislation (FELGTB, 2020). In the educational field, this materializes concretely in the existence of protocols that establish measures to facilitate inclusion and support for transgender students and their families. This is the case of communities such as Navarra in which there is an “Educational protocol in cases of transsexuality” (Government of Navarra, 2016), or in the autonomous community of the Basque Country with the "Protocol for educational centers in the accompaniment of trans students or students with non-normative gender behavior and their families" (Basque Government, 2016).

The development of positive attitudes towards sexual diversity among teachers is considered a key aspect for the creation of a school environment in which transgender students can feel safe (Gegenfurtner, 2017; González-Mendiondo & Moyano, 2023). Studies referring to teacher attitudes point to the importance of specific training on sexual diversity (Gegenfurtner, 2021; Scandurra et al., 2017), highlighting that lack of knowledge about transsexuality represents an influential factor in the development of discriminatory attitudes (Rodríguez & García, 2022). When teachers are asked directly, one of their main demands is more specific training on attention to sexual diversity (Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2020). Thus, teacher training is a key tool for the prevention of transphobia in the school environment (Moyano & Sánchez-Fuentes, 2020).

Qualitative research on the experiences of parents of transgender children reveals the difficulties that families encounter in supporting their children's transition. Studies such as those by Horton (2022) in the United Kingdom and Lorusso and Albanesi (2021) in Italy, point out that lack of knowledge is one of the main barriers that families initially encounter and suggest that schools do not always know how to guide and accompany families. Likewise, the only recent study that specifically addresses the role of the elementary school, carried out by Horton (2023) in the United Kingdom, shows the importance of school support for the proper development of these children, as well as in reducing the discrimination they endure.

The present studyResearch conducted on transgender minors in the Infant and Primary educational stages is scarce (Etxebarria-Perez-de-Nanclares et al., 2023; Fernández et al., 2018), with most of them focusing on the Secondary stage (McBride, 2021). On the other hand, there are very few qualitative studies on the experiences of families of transgender girls and boys (Abreu et al., 2019; Ehrensaft et al., 2019; Horton, 2022, 2023; Lorusso & Albanesi, 2021; Peterson, 2018). Within the framework of a broader research on the experiences of families who have undergone transition, the objective of this study is to explore the role played by the school, considering the school as an institution, the teachers and tutors, the peer group, other families and extracurricular activities, in the experiences of transsexual children and adolescents, before, during and after the transition process. For this purpose, the information obtained in the form of life narratives written by their mothers and fathers is analyzed. We divide the analysis into three distinct periods: pre-transit, during transit and post-transit, in accordance with other studies on the experiences of families of transgender minors (Abreu et al., 2019). The transit period is considered as that which elapses from the first explicit disclosure made to the closest environment until it is publicly communicated to the entire social environment.

MethodParticipantsThe mothers and fathers collaborating in the study are members of the Association of families of transsexual minors Naizen (until 2019, its name was Chrysallis Euskal Herria), which brings together families from the Autonomous Community of Navarra and the autonomous community of the Basque Country (Spain). This association provides support and training to families of transsexual minors with the aim of making this reality visible. We examined 22 stories written by mothers and fathers (17 written by the mother, 3 by the father and 2 jointly by the father and mother) of transsexual minors aged between 4 and 18 years, 13 of whom were girls (assigned as boy at birth) and 9 boys (assigned as girl at birth). The ages at which they transitioned ranged from 3 to 16 years (14 were under 12 years old and 8 were adolescents at the time of transition). In most cases (16 of 22) the time elapsed between the transit and the writing of the account does not exceed two years. One of the boys had died by suicide at the time of writing the story. All the families are of Spanish nationality and no exclusion criteria are established. Moreover, all of them were heterosexual couples and, except in one case, they were living together at the time of the transit. In the two autonomous communities in which the participating families reside, protocols for the educational care of transgender students have been in place since 2016. In six of the cases analyzed, the transition took place prior to the activation of these protocols and in the remaining sixteen they were already in force.

InstrumentVolunteer families are asked to write their story, giving them the following instructions: Express through a detailed account the life process of their son or daughter in a transsexual situation and of the whole family, from birth to the present time. Before, during and after the transition. Include in this account the experiences at home, at school, in the neighborhood, at the health services, the experience with the Administrations, associations, other families, etc. If required, you can include literal expressions or even dialogues. Both the "beautiful" aspects and the "difficult" moments. The text should be approximately eight pages long (Times New Roman format, size 12, single-spaced).

Convenience sampling is used by means of an announcement to all the families of the NAIZEN Association to volunteer for this study. No compensation is provided and their anonymity and confidentiality is guaranteed, with pseudonymization of the stories by the researcher in charge of receiving them, before they are qualitatively analyzed by the rest of the research team. This study has been approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of the Basque Country.

Data analysisThe MAXQDA 22 program was used for data analysis. After independent and simultaneous coding by two researchers of the team, the inter-coder agreement at the code level for the activated codes is 79%. It should be noted that this percentage refers exclusively to the agreement between the two codings on the presence of these codes in each of the documents analyzed. The disagreements observed are mainly due to the fact that the first evaluator groups the content into broader segments that are assigned to more general codes. Thus, the first evaluator codes a total of 104 segments of information while the second evaluator takes into account 128 segments. The information is organized in a codebook based on three categories: (1) Pre-transit experiences: information about the family’s experiences from birth until the child's explicit disclosure of his or her sexual identity; (2) Transit experiences: information about the family's experiences from the explicit disclosure of sexual identity until social recognition of sexual identity; and, (3) Post-transit experiences: information about the family's experiences after social recognition of sexual identity and up to the present.

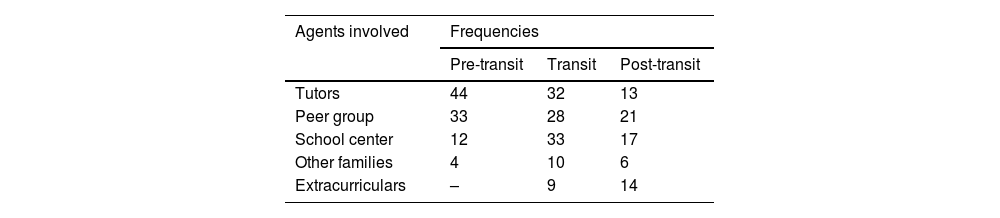

As can be seen in Table 1, for each of these categories, five agents interacting with the child and his or her family in the school context are distinguished, among which the following stand out: tutor, peer group, school center, other families and extracurricular activities. As can be observed, both in the pre-transit and during the transit process, most of the issues addressed by the participants allude to the role of the tutor, followed by the influence of the peer group, which becomes especially relevant in the post-transit.

When analyzing the data, we found two large thematic blocks transversal to the three moments indicated (pre-transit, transit and post-transit), and associated with the five different agents (tutors, peer group, school center, other families and extracurricular). The first, which has been called positive accompaniment, is made up of the facilities, acceptance and accompaniment experienced by the children and adolescents and their families, and the second, called difficulties, is made up of negative attitudes, lack of understanding and confusion with other realities such as non-normative gender behaviors.

ResultsTo illustrate the results, several fragments are shown that exemplify the various themes emerging from the analysis. After each fragment, and in order to contextualize it, the following is indicated in parentheses: pseudonym of the girl or boy protagonist of the story, sex (recognized after the transit), age at which the transit takes place, age at the time the story is written (this data does not appear in one of the cases, in which the minor committed suicide after the beginning of the transit) and authorship of the story: father (P), mother (M) or both (P/M). As an example: "Our daughter responded with flying colors: she worked very well, related perfectly with others and showed a commitment and responsibility that provoked the admiration of her teachers knowing as they did what she had gone through in her life" (Irene, girl, 10, 12, P).

This fragment corresponds to the story that narrates the process of Irene (pseudonym), who is a girl (assigned as a boy at birth), who is 10 years old at the time she made the transit and 12 years old when the story is written; the story has been written by her father (P).

Before transitMost of the stories describe how, in the face of their own uncertainties and suspicions, the school shows little understanding, questioning what the family claims and considering the situation as unstable. "She'll get over it" is the most common response, present in 12 of the 22 stories analyzed. "The teacher told me that she would get over it, that she thought she was fine despite the fact that I went to her on several occasions to complain about the insults and insults she received and the lack of friends" (Euri, girl, 6, 7, M).

The main difficulties encountered by families at these times arise from the teacher's interpretation of the child’s behaviors as non-conformity with gender roles, even when the family is already convinced that it is not a question of behavior, but of identity: "Some teacher told us, relax, she's just a little girl, but we had already been there and we already had the conviction that what Paul was saying was what she was" (Paul, boy, 4, 8, M).

In 3 of the 22 cases analyzed, families are faced with discrepant responses from the different educational agents in the center, which makes the process even more difficult: "I was surprised that it was the guidance counselor at the center who was the one who was complaining. For example, the tutor commented that lately he had gone from being a reserved child to being a very happy child and the counselor said that maybe my son was happy because with all this history he felt he was the center of attention" (Martín, boy, 15, 17, M).

In relation to the peer group, the difficulties translate into rejection for not fitting in with either the boys or the girls, which generates discomfort and isolation: "He was lonely because he didn't want to play with the girls and because the boys wouldn't accept him to play with them" (Mael, boy, 7, 8, M). "In 4th grade, when he was 9 years old, he experienced a crisis when he began to be ignored by the boys he used to play with because they no longer looked for him so much to play (…) It was a hard moment because he was rejected by boys and girls, he felt bad, he didn't want to go to school" (Unax, boy, 16, 18, M).

They are often the object of ridicule and insults because of their tastes and manners, which in some cases reaches the point of harassment, with some families even filing complaints. These insults also extend to extracurricular activities. This rejection and harassment becomes more acute as they approach puberty, with girls being more often the object of it: "Pussy, faggot, whore baby, were just some of the things they said to her" (Irene, girl, 10, 12, P).

One of the stories points out how the lack of knowledge about child transsexuality on the part of other mothers and fathers influences the non-acceptance of their sons and daughters: "A boy at school had respectfully told her that she could not be a girl because she had a dick, because her mistress had told her so, that this was not possible" (Haize, girl, 7, 12, M).

There are stories that point to experiences of positive accompaniment by the center and the peer group. Those who meet a professional who understands and accompanies the situation from the beginning are especially grateful, referring in one case to the tutor as "an angel from heaven" (Maria, girl, 4, 7, M). The stories confirm that everything is easier when the teachers have previous knowledge about child transsexuality:

"In her family there was also a case of a little trans person. For my daughter it was her fairy godmother because it would make her life easier that year" (Euri, girl, 6, 7, M).

Regarding the peer group, in cases of rejection and harassment, most of them have the support of a few friends who accept them as they are and defend them from the aggressions they suffer: "She had several allies, a couple of 'best plus' friends who were her great support, who made the whole transit much more bearable" (Euri, girl, 6, 7, M).

In some cases, they have friends who already treated them according to their sex before the transition. When the situation is accompanied from early childhood and the family and school accept the tastes and expressions without hindrance, the acceptance of the peer group also seems to be greater. Especially at younger ages, as shown in the following fragment in which the reaction of the classmates of a girl who, before the transition, when the others still consider her to be a boy, goes to school wearing a dress, is recounted: "The teachers told me that they had never seen him as happy as he was that day, his classmates welcomed him naturally" (Ane, girl, 4, 5, M).

Once the family decides to initiate the transition, the established school protocols are usually activated and a school approach is carried out, which translates into training sessions with the teachers, informative meetings with the rest of the families and interventions in the classroom. In all the reports, these interventions are valued as very positive: "I remember it as a very, very emotional day. We cried a lot at the sexologist's talk with the parents, many fathers and mothers cried too. We received a lot of warmth, support and respect from the parents" (Mael, boy, 7, 8, M).

Only one of the 22 reports states that the school continues to make the process difficult even when the school protocol has been activated: "There were teachers at the high school who told him that until he had his new name on his ID card they were not going to call him by his chosen name" (Unax, boy, 16, 18, M).

In the rest, once the educational teams already have information and external advice, it is reported how, in the end, they end up counting on the support and accompaniment of the center: "The process has been intense, but quite favorable with respect to the school, and the families of his classmates, I am very grateful for the respect and affection towards my son" (Paul, boy, 4, 8, M).

The day on which the transition is shared with the rest of the students appears, in all the stories, as a key moment, with "happy" being the adjective most used to describe the feelings of the boy or girl (present in 20 of the 22 stories). The tutor is usually in charge of informing the rest of the students that who they previously thought was a girl turns out to be a boy, or vice versa; and they announce, if it is the case, the change of name (in two of the stories analyzed, the minor decides to keep his or her name). In some cases, it is the child herself who explains her situation to the rest of the class: "And Eric at 4 years old had the courage to stand up in front of everyone and tell them he was a girl and not to get confused" (Eric, girl, 4, 6, P/M).

In some cases, teachers create their own materials to address the issue with students, showing special sensitivity: "To the teacher, it occurred to her to make a story to explain to Iker's classmates the transit we were going to live, she invented a very nice story" (Ikerne, girl, 5, 10, M).

When the transit begins in childhood, the accounts coincide in affirming that classmates take it very naturally: "Children fortunately do not have prejudices that we older people sometimes have and this facilitates respect" (Eric, girl, 4, 6, P/M).

When the transition occurs in adolescence, after the first moments of astonishment, in many cases peers show their support and even admiration: "We asked him why he was crying and he showed us his cell phone…all the messages were supportive: how brave you are, we support you to the fullest, we are with you… that's why he was emotional crying" (Aiur, boy, 16, ---, M).

Also in the out-of-school environment, the reports speak of positive accompaniment, indicating that they find support and acceptance: "The next step was to go to music school and I found there the support and understanding that I had not known in my environment until that moment, except in my family, of course" (Martin, boy, 15, 17, M).

And, when there are difficulties, they are usually related to the use of spaces such as showers or changing rooms: "In the summer activities I met a teacher who knew her and she didn't have time to tell me that, of course, if Euri went to the girls' bathroom, the mothers might complain" (Euri, girl, 6, 7, M).

The space dedicated in the stories to the experiences at school once the sexual identity is socially recognized is little in comparison with the previous moments. 19 reports indicate that, after the transition, the child manifests greater well-being in the school environment, which translates into higher performance and greater integration with the peer group: "After this transition in school, this same tutor told us that she saw her much better, that she had awakened more interest in all the activities and especially in drawing" (June, girl, 3, 4, P). "As an anecdote, it should be noted that on one of her first days of school she came home delighted because she had been named class subdelegate. Here we had a little proof that our daughter was doing very well on her own" (Julene, girl, 11, 17, M).

In those stories in which situations of harassment were experienced prior to transit, harassment seems to be reduced once the transit has taken place: "She thought she was going to be the center of attention and that people were going to pick on her again (…) But fortunately none of that happened, and a few days later she started going to class. As she knew some friends from the previous year, she gradually adapted to the new school and the new teachers and classmates, and peace returned to her being and to our home" (Irene, girl, 10, 12, P).

The main difficulties that teachers seem to encounter in adapting to the new situation are related to the way in which content on the human body and sex education is taught. Several accounts mention the support provided by associations with information and teaching resources: "Recently in class they dealt with the human body again and made them write the parts of the body in the didactic material of the association Chrysallis Euskal Herria. She came out of class happy to show us the two girls, one with a vulva and the other with a penis, that she had painted and to whom she had pointed out parts of the body" (Eric, girl, 4, 6, P/M).

After the transition, many of these children have experienced some important changes, such as moving to high school, attending summer camps or starting a new extracurricular activity. Regarding the new extracurricular activities, the most common decision is not to mention the transsexuality situation, being the use of common showers and changing rooms the only reason to do so: "Mael is a boy and no one needs to know what he has or doesn't have in his crotch. It is not relevant to treat and teach my son an activity or a sport" (Mael, boy, 7, 8, M).

The same happens with the transition to high school, as stated in one of the stories: "he is not going to come out of the closet every time there is a new group" (Irati, girl, 14, 16, M).

Although, in several stories, this change appears as a cause for concern for both the boy or girl and their families, and they choose to talk to the new center and work on the situation with the teachers and students.

DiscussionThe aim of this study was to explore the experiences of transsexual children and adolescents in the educational setting, before, during and after the social transition, based on the accounts of their mothers and fathers. The stories analyzed describe the process experienced at school in a similar way in all cases: a first moment of incomprehension and denial (difficulties) which, once the transition begins, is transformed into understanding and support (positive accompaniment) and which leads these boys and girls to an experience of greater well-being.

In relation to pre-transition experiences, most accounts report difficulties, skepticism and lack of knowledge and understanding on the part of teachers, who confuse what is happening with other realities such as non-normative gender behaviors, or who consider that what is expressed by these girls and boys is a transitory issue. However, scientific evidence indicates that girls and boys are aware of their sexual identity from very early ages (Ehrensaft, 2017; Moral-Martos et al., 2022), often between 2 and 4 years of age (Gómez-Gil et al., 2006). The role of teachers, especially their beliefs, is key, as these can result in the consolidation of moralistic and risky models (Reyes & Dreibelbis, 2020) with a restricted view of sexuality (Díaz de Greñu & Martínez, 2017). Therefore, it is necessary to highlight the importance of teacher training for the correct school approach to transsexuality (Gegenfurtner, 2017; Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2020; Scandurra et al., 2017). On the other hand, regarding the role of the peer group, there are different experiences ranging from bullying to accompaniment. In this sense, adult accompaniment is crucial since the lack of social support can generate discomfort, lack of security, suicidal attempts, drug addiction and loss of self-esteem (Factor & Rothblum, 2007).

During the transition process, there is a better accompaniment and use of didactic resources by teachers, and a majority support from the peer group, who tend to accept this step easily. The acceptance and validation of their identity by the school environment is a turning point for transgender students and generates feelings of happiness, reduction of distress and stress (Horton, 2022), as well as the development of better relationships and better academic results (Kuvalanka et al., 2014; Snapp et al., 2015).

As transgender girls and boys who have not yet transitioned approach puberty, they express significantly higher levels of distress and suffering, encounter more difficulties, obstacles and harassment, and their transition processes are much more complex and painful. This observation confirms that carrying out social transit later, far from being a sign of prudence, could lead to negative effects on their mental health such as anxiety, depression and even suicidal ideation (Horton, 2023; Landarroitajauregui, 2018; Olson et al., 2016).

The analyzed accounts show that waiting is not innocuous, but can produce negative sequelae in their psychosocial development, while the accompaniment and acceptance of their sexual identity since childhood can favor the construction of a secure bond and the development of greater resilience, as stated by Rafferty et al. (2018), which decreases the risk of internalized psychopathologies, reducing the levels of depression and anxiety (Olson et al., 2016).

After social transit, all accounts reflect positive consequences for the psychosocial and academic development of these girls and boys, so that accompanying transit seems to be an effective way to prevent discomfort (Horton, 2023; Olson et al., 2016; Rafferty et al., 2018). In accounts that capture situations of harassment prior to transit, these disappear after transit. Our findings, contrast with previous studies that indicate greater difficulties, such as the one conducted by Kosciw et al. (2015), in which it is indicated that, in LGBT students in Secondary School, disclosure is related to greater victimization, although at the same time they experience higher self-esteem and lower levels of depression. It is likely that, in our sample, whose ages at the time of transit were lower, the adaptation of the environment was easier, reducing the level of victimization and harassment, more characteristic of secondary school (Moyano & Sánchez-Fuentes, 2020).

Among the limitations of the present study, it should be noted that the participating families are members of the same association of families of transsexual minors, in the territorial scope of two autonomous communities, which probably leads them to have a shared vision of transsexuality. It would be convenient to extend the study to families from other autonomous communities, to families from other associations and to families that do not belong to any association, in order to have other experiences and perspectives. On the other hand, more mothers than fathers participated, an imbalance that undoubtedly conditions the accounts of the experiences lived. Since it is based on retrospective information, there may be some recall bias, given the great emotional charge of the experiences being recounted, so it would be advisable to carry out other studies using other instruments that allow recording specific behaviors and/or situations on a day-to-day basis.

This is one of the first qualitative studies carried out in Spain that provides experiences related to the educational environment of families in relation to the transit process in their sons and daughters during childhood and, to our knowledge, it is the first to talk specifically about transsexual minors, differentiating this reality from others close to it such as non-normative gender behaviors or non-binarism. All of them share some elements, especially stigma and exclusion, and, therefore, must be addressed from the school. However, as they are different realities, it is essential to know the specific experiences and needs of each one of them in order to be able to adapt the responses and actions, thus enabling a better accompaniment of them.

Future studies should deepen the analysis of the quality of life and mental health of transsexual students, as well as their families, during the transition process and afterwards, providing indicators to improve care and counseling by education professionals. On the other hand, it will be necessary to address this issue through longitudinal designs, which will allow a follow-up from childhood to adolescence or youth, thus providing a broader and more dynamic view of these transition processes. It would also be of interest to analyze the differences that occur in the transition processes between cases before and after the entry into force of the educational protocols for transsexual students. Finally, there is a need for research focused on the role of teachers to deepen their capacity and preparation to address aspects related to the sexual identity of students and the different facts of sexual diversity, this being a key issue, increasingly necessary, so that teachers can carry out an adequate accompaniment in collaboration with families.

FinancingThis study is not externally funded.