To investigate the impact of an authentic leader on employees’ psychological capital (PsyCap), job satisfaction, job insecurity, and intentions to quit the organisation, mediation analyses, as well as a conditional process analyses, were conducted using data collected from an offshore organisation. Findings showed that employees who perceived their leader as being authentic reported more job satisfaction and less job insecurity and intentions to quit the organisations. Moreover, results also showed an indirect effect of authentic leadership through PsyCap. Finally, the influence of the captains’ authenticity did not vary depending on whether or not the captain was the employees’ immediate superior. Results from this study suggest that efforts should be made to focus on the components of an authentic leader during recruitment, training, or intervention. Conclusively, employees working in the marine/offshore sector are faced with persistent fluctuations and uncertainties, and having an authentic leader will promote job satisfaction, while reducing both job insecurities and turnover intentions among employees.

Con objeto de investigar la influencia del líder auténtico en el capital psicológico de los trabajadores (cap-psi), la satisfacción en el trabajo, la inseguridad laboral y la intención de abandonar la empresa, se llevaron a cabo análisis de mediación y de procesos condicionales con datos sacados de una empresa offshore. Los resultados muestran que los trabajadores que percibían a su jefe como auténtico estaban más satisfechos y con menor inseguridad laboral e intención de abandonar la empresa. También había un efecto indirecto del liderazgo auténtico a través del capital psicológico. Por último, la influencia de la autenticidad de los jefes no variaba por que el jefe fuera el inmediato superior. Estos resultados indican que habría que hacer hincapié en los componentes del líder auténtico durante el reclutamiento, la formación y la intervención. Como conclusión, los trabajadores del sector marino/offshore se enfrentan a continuas fluctuaciones e incertidumbre, por lo que la existencia de un liderazgo auténtico aumentaría la satisfacción a la par que disminuirían tanto la inseguridad laboral de los trabajadores como su intención de abandono.

John C. Maxwell, a critically acclaimed American expert on leadership once said that “everything rises and falls on leadership” (Maxwell, 2007, p. 267). Taken literally, this means that simple organisational variables like a successful psychosocial work environment, employees’ satisfaction, absenteeism, and presentism, job insecurity, and intentions to quit the organisation, to name a few, could be appropriated to the leadership's efforts or lack thereof. The present study was conducted among workers in the offshore oil and gas shipping re-supply industry. Workers in this particular field have been purported to epitomize safety critical organisations (SCOs). Seafaring as a profession has been regarded as a very demanding endeavour usually occurring within a dangerous environment (Hystad, Saus, Sætrevik, & Eid, 2013). According to Bergheim, Nielsen, Mearns, and Eid (2015), the working environment in the maritime sector appears to expose its workers to high rates of hazards, accidents, and catastrophes. Furthermore, the researchers maintain that “happy ship” is a very common expression among these workers, meaning that “job satisfaction and individual motivation are considered crucial elements in maritime organisations” (Bergheim et al., 2015, p. 27). Additionally, job insecurity and turnover intentions are among the ills of the maritime sector, potentially leading concerned employees to the violation of safety procedures, under-reporting of accidents, as well as decreased organisational citizen behaviour and commitment (Beecroft, Dorey, & Wenten, 2008; Cole & Bruch, 2006; Coyne & Ong, 2007; Probst, Barbaranelli, & Pettita, 2013; Probst & Ekore, 2010). In relation to the above, what can a leader do to increase job satisfaction while simultaneously reducing job insecurities and turnover intentions among employees? Concretely, can a leader influence employees’ perception of job insecurity, turnover intentions and job insecurity?

Today, we witness an upsurge in various types of leadership theories (Antonakis, 2003; Avolio & Bass, 2002; Gardner, Avolio, Luthans, May, & Walumbwa, 2005; Skogstad, Einarsen, Torsheim, Aasland, & Hetland, 2007; Yukl, 2008). One of such theories is the authentic leadership style with its origin from the domain of positive psychology and positive organisational behaviour (Luthans & Avolio, 2003). As its name implies, it is described as the sense of personal ownership to one's “experiences, be they thoughts, emotions, needs, preferences, or beliefs, processes captured by the injunction to oneself” as well as behaviours that are consistent with the true self (Harter, 2005, p. 382).

The definition of authentic leadership style as a construct is built upon many underlying dimensions (Walumbwa, Avolio, Gardner, Wernsing, & Peterson, 2008). Luthans and Avolio (2003, p. 243) were first out to define authentic leadership as the “process that draws from both positive psychological capacities and a highly developed organisational context, which results in both greater self-awareness and self-regulated positive behaviours on the part of leaders and associates, fostering self-development”. So, an authentic leader not only feeds on psychological abilities in order to reach positive results, she also has a highly developed organisational contexts, all of which results into self-development both for the leader and her associates. The authentic leader's positive influence on her subordinates has made this construct attractive to scholars. This probably explains why many studies (e.g., Borgersen, Hystad, Larsson, & Eid, 2014; Rego, Sousa, Marques, & Cunha, 2012) have investigated the authentic leaders’ role in organisational variables like job satisfaction, employees’ performance, employees’ creativity, and safety perceptions, among other things.

In the current study, we will build upon earlier studies and investigate if authentic leadership style plays any role in tangible organisational variables like employees’ job satisfaction, whether or not employees feel secured in their positions, and lastly, employees’ intentions to quit the organisation. We propose that authentic leadership exerts an influence not only directly, but also indirectly through a set of psychological qualities known as “psychological capital” (PsyCap) (Luthans, Youssef, & Avolio, 2007). In what follows, we will briefly expand our discussion of authentic leadership and why it may influence follower PsyCap. In the final part of the introduction, we will give an overview of the current study and present our hypotheses. This part will also contain a brief discussion of our organisational outcomes variables.

Authentic Leadership and Psychological CapitalApart from the definition of authentic leadership given above, there have been attempts by several other researchers to give their own definition of authentic leadership style. For instance, Avolio, Walumbwa, and Weber (2009, p. 424) described authentic leadership style as a sequence “of transparent and ethical leader behaviour that encourages openness in sharing information needed to make decisions while accepting input from those who follow”. Through this definition, it is apparent that the actions of an authentic leader influence her subordinates. Avolio, Luthans, and Walumbwa (2004, as cited in Avolio, Gardner, Walumbwa, Luthans, & May, 2004) also give a more comprehensive definition of authentic leaders in their work on authentic leadership. These researchers define authentic leaders as: Those who are deeply aware of how they think and behave and are perceived by others as being aware of their own and others’ values/moral perspectives, knowledge, and strengths; aware of the context in which they operate; and who are confident, hopeful, optimistic, resilient, and of high moral character (p. 4, as cited in Avolio et al., 2004).

In conjunction with the above, there has been an increase in studies implicating PsyCap as a mediator in the relationship between authentic leadership style and several organisational variables (Rego et al., 2012; Spence Laschinger & Fida, 2014; Wang, Sui, Luthans, Wang, & Wu, 2014). According to Luthans et al. (2007, p. 3), PsyCap can be described as: An individual's positive psychological state of development and is characterized by: (1) having confidence (self-efficacy) to take on and put in the necessary effort to succeed at challenging tasks; (2) making a positive attribution (optimism) about succeeding now and in the future; (3) persevering toward goals and, when necessary, redirecting path to goals (hope) in order to succeed; and (4) when beset by problems and adversity, sustaining and bouncing back and even beyond (resiliency) to attain success.

The significance of PsyCap in organisations has been demonstrated in several recent studies.

For example, Avey, Luthans, and Youssef (2010) investigated the value of PsyCap in predicting work attitudes and behaviours among employees selected from a spectrum of organisations and jobs. The results from this study showed that PsyCap was positively related to organisational citizenship behaviours and negatively related to organisational cynicism, counterproductive work behaviours, and intentions to quit the organisation. A plethora of additional studies corroborate the importance of PsyCap, demonstrating favourable impact of PsyCap on entrepreneurs (e.g., Jensen & Luthans, 2006), on mental health and substance abuse (Krasikova, Lester, & Harms, 2015), job satisfaction and safety perceptions (Bergheim et al., 2015), as well as on employees’ attitudes, behaviours, and performance (Avey, Reichard, Luthans, & Mhatre, 2011; Luthans, Avolio, Walumbwa, & Li, 2005).

Authentic leadership style has previously been found to have a positive effect on employees’ PsyCap (Hystad, Bartone, & Eid, 2014; Rego et al., 2012). For instance, in a study conducted among workers in the offshore oil and gas industry, Hystad et al. (2014) showed that part of the association between authentic leadership and a positive safety climate was mediated through the effect that authentic leadership had on the subordinates’ PsyCap. There are sound theoretical reasons for expecting authentic leadership to have a positive influence on employees PsyCap. For example, an authentic leader's balanced processing of information, relational transparency, and ability to practice what she preaches may serve to enhance self-efficacy and resilience in workers. In line with Bandura's (1997) theory of social modelling, an authentic leader's self-awareness and moral perspective could further provide a model for workers, inspiring them to believe in positive work outcomes (optimism) and future work accomplishments (hope). From this line of reasoning, we suggest that authentic leadership not only influences employee job satisfaction,–insecurity, and intentions to quit directly, but also indirectly through the impact that it has on the PsyCap of employees.

Overview of the Current StudyTo reiterate, the present study seeks to investigate not only the direct relationship between authentic leadership and intentions to quit the job, job satisfaction and -insecurity, but also the indirect relationship through PsyCap. Below, we briefly present and discuss our organisational outcome variables.

According to Arnold, Randall, and Patterson (2010), the concept of job satisfaction has been viewed to be important for two reasons. The first is that it is perceived to be an indicator of an employee's psychological well-being or mental health. Added to this, there are reasons to believe that an unhappy worker is more often than not an unhappy person. Secondly, the view that attitudes affect behaviour instigates the assumption that job satisfaction often motivates employees and, as a result, influences performance positively (Matthiesen, 2005; Pratkanis & Turner, 1996; Spector, 1997).

Job insecurity is closely related to job satisfaction, in as much that the two are consistently found to co-occur (e.g., Ashford, Lee, & Bobko, 1989; Sverke & Hellgren, 2002). Modern day working life brings with it a high dose of strain and intricacies. Changes as a result of incessant rise in the level of dependency between countries, rapidly fluctuating consumer markets, and the heightened demands for flexibility has impelled organisations into either (1) employing strategies for accumulating more gains or (2) reducing cost, for example, through cutbacks and downsizing (Dekker & Schaufeli, 1995; Sverke, 2004; Sverke & Hellgren, 2000; Sverke, Hellgren, & Naswall, 2002). While the literature on job insecurity started with lots of focus on its influence on employees’ well-being (e.g., Greenhalgh & Rosenblatt, 1984; Sverke et al., 2002), it appears that scholars are also extending the area of research to safety of employees (Probst, Brubaker, & Barsotti, 2008). Probst (2011), for instance, have suggested that job insecurity could affect employees’ safety in three ways; (1) through negative influence on employees’ cognitive resources and thus deterioration in their attentional capacity towards safety, (2) through propelling employees to focus their attention on production, believing that increased production rate might secure their jobs, and (3) through perceptions of a reduced organisational emphasis on safety, which in turn results in a reduced levels of safety compliance.

Finally, turnover intentions have received considerable attention in the literature, perhaps because it has often been regarded as a probable antecedent to actual turnover (e.g., Crossley, Bennett, Jex, & Burnfield, 2007; Griffeth, Hom, & Gaertner, 2000; Oluwafemi, 2013; Steel & Ovalle, 1984; Tett & Meyer, 1993). Apart from the relationship with actual turnover, intentions to quit/turnover intentions have also been found to be related to several other work environment variables. For instance, turnover intentions have been found to be negatively related to organisational citizenship behaviour (Coyne & Ong, 2007), organisational identification and job satisfaction (Van Dick et al., 2004), person-organisation fit (Liu, Liu, & Hu, 2010), public service motivation (Bright, 2008), and organisational commitment (Beecroft et al., 2008; Cole & Bruch, 2006).

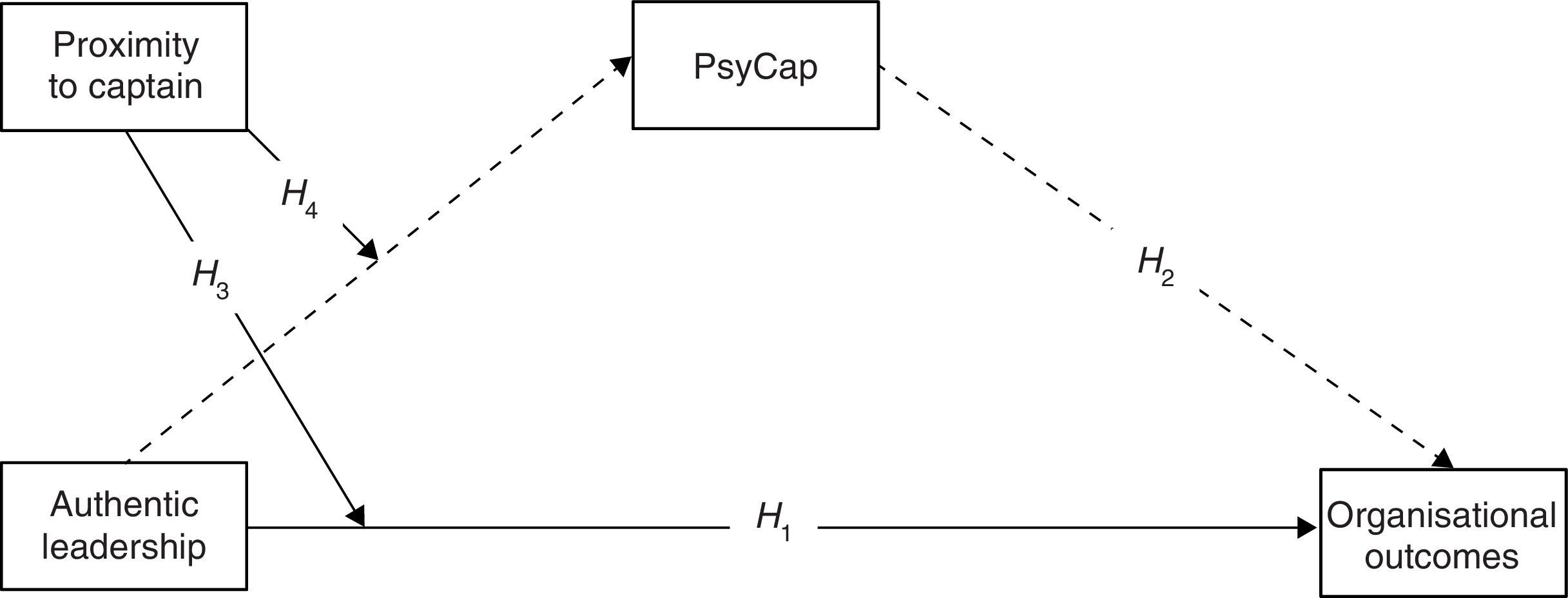

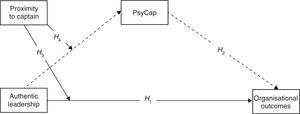

Based on the discussion presented so far, this study will focus on the following hypotheses:

H1. There will be a direct effect of authentic leadership on job satisfaction, intentions to quit, and job insecurity.

H2. There will be an indirect effect of authentic leadership on job satisfaction, intentions to quit, and job insecurity through psychological capital.

The company in the present study operates with several distinct work departments, as do many organisations. Although the captain is the supreme leader on the ship, employees on the ships are grouped under section leaders and not all the crew work in close proximity to the captain. Instead, many crewmembers work in closer contact with their immediate supervisor (for example first officer, chief engineer, or steward) than they do with the captain. Since the captain works more closely with some staff members than others, it is plausible to argue that the captains’ leadership style will rub off to a larger degree on those who works in close proximity to the captain. This line of thought has led to the two hypotheses below:

H3. The direct effect of the captain‘s leadership is expected to be stronger for those who have the captain as their immediate supervisor.

H4. The indirect effect of the captain's leadership through PsyCap is expected to be stronger for those who have the captain as their immediate supervisor.

Figure 1 summarises our hypotheses and shows the presumed relations between authentic leadership, PsyCap, and organisational outcomes.

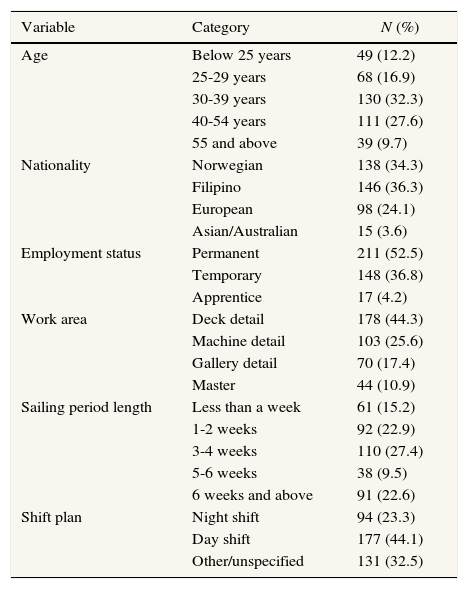

MethodParticipantsOur sample consists of 402 seafarers working in the offshore oil and gas shipping re-supply industry. Of the total sample, 49 (12.2%) of the workers were 24 years old or younger, 130 (32.3%) were between 30 and 39 years old, 111 (27.6%) were between 40 and 54 years old, and 39 (9.7%) were 55 years or older. The number of women eligible for the present study was so low that the decision was reached not to record sex in order to protect the anonymity of all participants. Regarding nationality, the sample consists mainly of Norwegians (n=38, 34.2%) and Filipinos (n=146, 36.3%). Other nationalities include Europeans (n=98, 24.1%) and Asian/Australian (n=15, 3.6%). Other demographical variables, including participants’ employment status and years of experience, are presented in Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of the Participants.

| Variable | Category | N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Below 25 years | 49 (12.2) |

| 25-29 years | 68 (16.9) | |

| 30-39 years | 130 (32.3) | |

| 40-54 years | 111 (27.6) | |

| 55 and above | 39 (9.7) | |

| Nationality | Norwegian | 138 (34.3) |

| Filipino | 146 (36.3) | |

| European | 98 (24.1) | |

| Asian/Australian | 15 (3.6) | |

| Employment status | Permanent | 211 (52.5) |

| Temporary | 148 (36.8) | |

| Apprentice | 17 (4.2) | |

| Work area | Deck detail | 178 (44.3) |

| Machine detail | 103 (25.6) | |

| Gallery detail | 70 (17.4) | |

| Master | 44 (10.9) | |

| Sailing period length | Less than a week | 61 (15.2) |

| 1-2 weeks | 92 (22.9) | |

| 3-4 weeks | 110 (27.4) | |

| 5-6 weeks | 38 (9.5) | |

| 6 weeks and above | 91 (22.6) | |

| Shift plan | Night shift | 94 (23.3) |

| Day shift | 177 (44.1) | |

| Other/unspecified | 131 (32.5) |

The data for the project was collected in the fall of 2013. Questionnaires were sent out to 926 crew members working on 22 different vessels with operations mainly in the North Sea and Southeast Asia. The shipping company's onshore shipping and forwarding agent took charge of the distribution and administration of the questionnaires through mailing the questionnaires to potential respondents. Subsequently, the respondents themselves were asked to return the filled questionnaires in pre-paid, unmarked, and sealed envelopes to the main researcher in order to safeguard anonymity. Respondents were informed that it was a voluntary exercise to participate, and that participants could, whenever they so wish, withdraw from the study without any given reason for such decision. Furthermore, participants were also informed of the high degree of confidentiality involved in the study, making them aware that their responses could never be traced back to them.

MeasuresAuthentic leadership. Authentic leadership was measured using the Authentic Leadership Questionnaire (ALQ; Walumbwa et al., 2008). The ALQ contains 16 items where participants are asked to rate their experiences of leadership behaviours at work. The ALQ is made up of questions that try to check if the leadership encourages workers to speak their minds, admits mistakes, and focuses on core values and ethical conducts among other things. Concretely, the scale is further sub-divided into four different dimensions: the leadership's relational transparency, balanced processing, internalised moral perspective, and self-awareness. The total score of all the items was used in the present study. Sample questions from the scale are “My master analyzes relevant data before coming to a decision” and “My master shows he understands how specific actions impact others”. “Master” in this case refers to the captain of the ship. Respondents were asked to rate these questions from 1=not at all to 5=frequently if not always. A high score is a pointer to a high prevalence of authentic leadership style and a low score means a low existence of the authentic leadership style. Cronbach's alpha was found to be .95 for authentic leadership in the present study.

Psychological capital. PsyCap was measured using an abridged 12-item psychological capital questionnaire that is drawn from the original 24-items scale developed by Luthans et al. (2007). Even though the 12-item version used in the present study was a short version of the original 24-items scale, it still contains the four major components of the original scale. Sample items are: “I feel confident in contributing to discussions about long-term work organisation and work schedules on board” (efficacy); “I can think of many ways to reach my current work goals” (hope); “I usually take stressful things at work in stride” (resilience); and “With regard to my job, I am optimistic about my future” (optimism). All items were measured on a six-point scale that range from 1=strongly disagree to 6=strongly agree. The Cronbach's alpha for psychological capital in the present study was .91.

Job satisfaction. Job satisfaction was measured using the Brayfield and Rothe (1951) job satisfaction scale as suggested by some researchers (Hauge, Skogstad, & Einarsen, 2010; Hetland, Hetland, Mykletun, Aarø, & Matthiesen, 2008; Judge, Parker, Colbert, Heller, & Ilies, 2001; Nielsen, Bergheim, & Eid, 2013). The original scale contains 18 items measuring employees’ level of job satisfaction. Judge et al. (2001) and a host of other scholars (Hauge et al., 2010; Hetland et al., 2008) have found a short version of this scale to be a reliable indicator of job satisfaction. Sample items are “I feel fairly satisfied with my present job” and “Most days I am enthusiastic about my work”. The scale was measured on a five-point scale (1=completely disagree to 5=completely agree). For a better internal consistency, the present study does not include the item “Each day at work seems like it will never end” as some other studies have done (Hetland et al., 2008; Judge et al., 2001). The job satisfaction scale as used in the present study thus consists of four items in total. The internal consistency for the job satisfaction scale was found to be satisfactory (Cronbach's alpha=.64). Although somewhat low, this is still acceptable given the brevity of the scale (four items) and the reliability estimates found in other studies (e.g., Tavakol & Dennick, 2011).

Intentions to quit. Intention to quit was measured using a scale suggested by Nielsen et al. (2013). Although the original scale had only three items “I often think of leaving the shipping company”, “It is very possible that I will look for a new job within the next 12 months”, and “I wish to move to an onshore job within the next 12 months”, one more item was added to the scale in the present study: “If I were able to choose again, I would have chosen to work for the same organisation”. The internal consistency for the scale was also found to be good (Cronbach's alpha=.74).

Job insecurity. Job insecurity was measured using one out of the two dimensions of job insecurity developed by Isaksson, Hellgren, and Pettersson (1998, as cited in Hellgren, Sverke, & Isaksson, 1999). According to these researchers, the two dimensions were based on two classifications: firstly, job insecurity arising from seeming threats regarding continuity of the job, and secondly, those matters pertaining to threats to the continuity of the vital parts of the job features. These two perceived threats followed the path laid down by Greenhalgh and Rosenblatt (1984, as cited in Hellgren et al., 1999). The present study only focused on the first dimension, that is, job insecurity that arises from perceived threats to employees’ job continuity. The scale as used in the present consisted of three items. Sample items are “I worry I may have to leave my job before I planned” and “There is a chance that I will have to leave my job during the next year”. Respondents could give their responses on a five-point scale (1=completely disagree to 5=completely agree). The internal consistency for the scale was also found to be satisfactory (Cronbach's alpha=.75).

Proximity to the captain. Respondents were also asked to indicate who they regarded as their immediate supervisor. Respondents could choose between six possible options: “Master”, “First officer”, “Chief engineer”, “Steward”, “Foreman”, and “Other”. Responses to this question were dichotomised such that participants indicating “Master” constituted one category and all the rest constituted another category.

Statistical AnalysisTraditionally, tests of mediation have followed the “3-step” approach outlined in Baron and Kenny's (1986) seminal paper. Although still widely used, this approach is now recognised as problematic on multiple grounds (see, e.g., Hayes, 2013; MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002). In order to test our Hypotheses 1 and 2, we therefore used the “PROCESS” macro script developed by Hayes (2013) as a supplement program to SPSS instead. This choice was made because of the flexibility of the program, as well as its ability to provide tests of statistical inference of the actual indirect effect.

To test our Hypotheses 3 and 4, we performed what is known as moderated mediation or conditional process analysis (Edwards & Lambert, 2007; Hayes, 2013; Preacher, Rucker, & Hayes, 2007). Moderated mediation occurs when two independent variables (in this case the authentic leadership construct and the “proximity to captain” variable) jointly influence a proposed mediator (PsyCap), which in turn affects a dependent variable (job satisfaction, job insecurity, and intentions to quit) (Hayes, 2013; Morgan-Lopez & MacKinnon, 2006). Hayes (2013, p. 3) has argued that a mediation process can be said to be moderated if the “proposed moderator variable has a nonzero weight in the function linking the indirect effect of X on Y through M to the moderator”, and proceeds to name this weight the index of moderated mediation. An important feature of this index is that a test of statistical significance does not require evidence of a statistically significant interaction between the presumed moderator and any of the variables in the mediation chain. That is, a significant interaction between the “proximity to captain” variable and authentic leadership is not a requirement of establishing moderation of the indirect effect of authentic leadership through PsyCap. Rather, the statistical significance rests upon whether the weight–the index of moderated mediation–itself is different from zero.

There are several ways to proceed to test the null hypotheses that the corresponding population values of the indirect effect or the index of moderated mediation are zero, such as computing standard errors for the weights and performing Sobel-type tests (Sobel, 1982, 1986). Because of the known distributional problems with products of regression weights (i.e., they are not normal), Hayes (2013) recommends using bootstrap confidence intervals. Among some of the advantages of the procedure described by Hayes (2013) is the ability to provide bootstrap confidence intervals for the indirect effects and the index of moderated mediation.

To summarise, in order to test Hypotheses 1 and 2, we computed three different models, corresponding to our three organisational outcome variables of job satisfaction, job insecurity, and intention to leave. To test our Hypotheses 3 and 4 we performed what is known as moderated mediation or conditional process analysis. For each of the three models, 1,000 bootstrap resamples were used to estimate the confidence intervals.

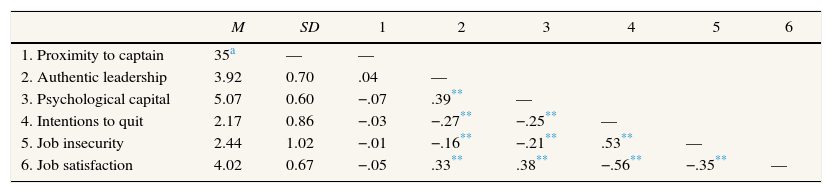

ResultsDescriptive characteristics of the participants included in this study are presented in Table 1 below, while correlations, means, and standard deviations of the variables included in this study are presented in Table 2.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Inter-correlations (Pearson r) between Variables.

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Proximity to captain | 35a | — | — | |||||

| 2. Authentic leadership | 3.92 | 0.70 | .04 | — | ||||

| 3. Psychological capital | 5.07 | 0.60 | −.07 | .39** | — | |||

| 4. Intentions to quit | 2.17 | 0.86 | −.03 | −.27** | −.25** | — | ||

| 5. Job insecurity | 2.44 | 1.02 | −.01 | −.16** | −.21** | .53** | — | |

| 6. Job satisfaction | 4.02 | 0.67 | −.05 | .33** | .38** | −.56** | −.35** | — |

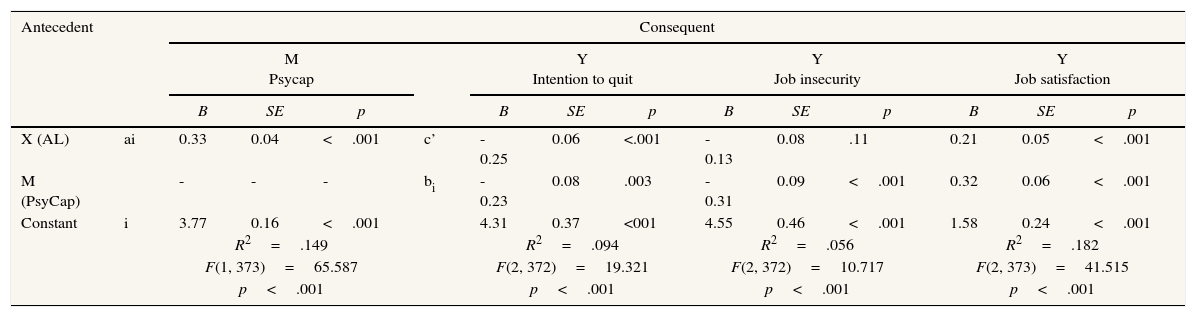

Table 3 presents results from the three models testing the direct and indirect effects of authentic leadership on employee job satisfaction, job insecurity, and intentions to quit the organisation. The direct effect of authentic leadership, controlling for the effect of PsyCap, was statistically significant for intentions to quit (B=-.25, p<.001) and job satisfaction (B=.21, p<.001), but not for job security (B=-.13, p=.11).

Mediation Analyses of Authentic Leadership on Intention to Quit, Job Insecurity, and Job Satisfaction via Psychological Capital.

| Antecedent | Consequent | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M Psycap | Y Intention to quit | Y Job insecurity | Y Job satisfaction | |||||||||||

| B | SE | p | B | SE | p | B | SE | p | B | SE | p | |||

| X (AL) | ai | 0.33 | 0.04 | <.001 | c’ | -0.25 | 0.06 | <.001 | -0.13 | 0.08 | .11 | 0.21 | 0.05 | <.001 |

| M (PsyCap) | - | - | - | bi | -0.23 | 0.08 | .003 | -0.31 | 0.09 | <.001 | 0.32 | 0.06 | <.001 | |

| Constant | i | 3.77 | 0.16 | <.001 | 4.31 | 0.37 | <001 | 4.55 | 0.46 | <.001 | 1.58 | 0.24 | <.001 | |

| R2=.149 | R2=.094 | R2=.056 | R2=.182 | |||||||||||

| F(1, 373)=65.587 | F(2, 372)=19.321 | F(2, 372)=10.717 | F(2, 373)=41.515 | |||||||||||

| p<.001 | p<.001 | p<.001 | p<.001 | |||||||||||

Note. AL=authentic leadership; PsyCap=psychological capital.

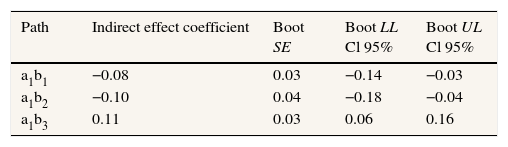

The results from the mediation analyses further showed that there were indirect relationships between authentic leadership and all three organisational outcome variables via PsyCap. Table 4 presents the indirect regression weights for all three models. The indirect regression weights are simply the products of the a and b weights in Table 3. As noted in the method section, bootstrap confidence intervals were used as statistical inference. These intervals are presented alongside the indirect effects in Table 4. As none of these bootstrap confidence intervals include zero in their boundary, we can conclude that the results support indirect effects of authentic leadership on employee job satisfaction, job insecurity, and intentions to quit through PsyCap.

Indirect Effects for Authentic Leadership on Intention to Quit, Job Insecurity, and Job Satisfaction.

| Path | Indirect effect coefficient | Boot SE | Boot LL Cl 95% | Boot UL Cl 95% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a1b1 | −0.08 | 0.03 | −0.14 | −0.03 |

| a1b2 | −0.10 | 0.04 | −0.18 | −0.04 |

| a1b3 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.16 |

Note. Boot SE=Bootstrap standard error; Boot LL=lower limit Bootstrap 95% confidence interval; Boot UL=upper limit Bootstrap 95% confidence interval.

a1b1: Authentic leadership → PsyCap → Intention to quit

a1b2: Authentic leadership → PsyCap → Uncertainty

a1b3: Authentic leadership → PsyCap → Job satisfaction

Next, conditional process analyses were conducted to investigate the effect of having the captain as an immediate supervisor. Results from these analyses showed that the interaction terms between authentic leadership and the “proximity to captain” variable did not predict any of the three outcome variables. Our Hypothesis 3 was therefore not supported. Furthermore, the indices of moderated mediation showed that the indirect effects of authentic leadership on the three outcomes did not differ between the group who had the captain as the immediate leader and the group who did not have the captain as the immediate leader. Specifically, the index of moderated mediation for the analysis involving intentions to quit was .015, with an accompanying bootstrap confidence interval between -.047 and .06; for the analysis involving job insecurity it was .02 (bootstrap CI=-.04–.09); and for the analysis involving job satisfaction it was -.02 (bootstrap CI=.-10–.05). All confidence intervals included zero within their boundary and our Hypothesis 4 was therefore not supported.

DiscussionThe aim of this paper was to investigate the direct relationships between an authentic leadership style and job satisfaction, job insecurity, and intentions to quit (Hypothesis 1). A second aim was to examine any indirect relationship between authentic leadership and the three outcome variables through PsyCap (Hypothesis 2). We also assumed that those employees working directly under the captain would be more influenced by his authenticity. In effect, we expected stronger direct (Hypothesis 3) and indirect effects (Hypothesis 4) of authentic leadership style among those employees working closely with the captain.

Our results are mostly in line with Hypothesis 1. Authentic leadership predicted intentions to quit and job satisfaction, but not job insecurity. As a whole, our results point towards the importance of having a leader that is regarded as authentic. As previously mentioned, intentions to quit are often related to actual turnover (e.g., Crossley et al., 2007; Tett & Meyer, 1993). Turnover is recognised to be costly for the organisation. When an employee leaves an organisation (whether voluntarily or involuntarily), the organisation will have to go through the process of looking for a replacement of this employee. This process entails designing descriptive job characteristics for the position, advertising, recruiting/hiring, as well as training and development in some cases. All of these steps can cause cutbacks in performance, and might even have a negative impact on the safety procedures and regulations at work (Ready, 2007). In fact, a recent meta-analysis of turnover and organisational performance showed that the relation between employee turnover and organisational performance was strongest when performance was operationalised in terms of safety metrics (Hancock, Allen, Bosco, McDaniel, & Pierce, 2013). Turnover is recognised as real problem in the maritime industry (North Sea Offshore Authorities Forum, 2009), the setting in which the current study took place, and our finding that authentic leadership is related to less turnover intentions could therefore be of real value.

Our finding that authentic leadership influences employee job satisfaction is interesting on multiple grounds. First, an unhappy worker is more often than not an unhappy person. The ability of authentic leaders to increase workers’ job satisfaction is therefore important from the perspective of the wellbeing of the employees. Second, employee job satisfaction could be essential for safety. A safe workplace is obviously a prerequisite for employees to be happy and satisfied (e.g., Nielsen, Mearns, Matthiesen, & Eid, 2011). There is, however, also evidence that employee job satisfaction is related to accident involvement and perceptions of a positive safety climate (Ayim Gyekye, 2005; Barling, Kelloway, & Iverson, 2003), as well as the tendencies to violate company's safety procedures (Gyekye, 2006). A likely explanation is that job satisfaction acts like a motivational force that affects behaviour (Matthiesen, 2005; Pratkanis & Turner, 1996).

Although authentic leadership did not have direct relation with job insecurity, it did have an influence via PsyCap. This is important because job insecurity has been linked to employee behaviour in several ways. Constantly worrying about their jobs may negatively influence the cognitive capacity of employees and limit the amount of attention available for safety issues. Job insecurity may further drive employees to focus on production at the cost of safety, believing that an increased production rate might secure their jobs (Probst, 2011). As is the case with job satisfaction, job insecurity probably also works like a motivational force, except in the opposite direction. Probst and Brubaker (2001), for instance, found that employees who reported high perceptions of job insecurity also reported lower safety motivation and compliance with safety regulations, which in turn were related to higher frequencies of workplace injuries and accidents. Similar results were reported in a meta-analysis conducted by Sverke et al. (2002). Among other things, they found that the experience of job insecurity was associated with negative organisational attitudes and negative job attitudes.

In addition to job insecurity, authentic leadership also had indirect effects via PsyCap on job satisfaction and intentions to quit. Our Hypothesis 2 was therefore supported. As such, our findings are in line with past studies on authentic leadership and employees’ PsyCap (Hystad et al., 2014; Jensen & Luthans, 2006). This does not come as a surprise judging by for instance Cloninger's (1996) definition of authenticity. According to Cloninger (1996), an authentic leader is someone with the ability to perceive both emotional cues and different facets of the social environment she finds herself without any form of distortion. Cloninger (1996, p. 258) maintains that an authentic leader is able to incorporate all of the aspects “of experience and comes to an inner sense of what is right for him or her. This sense is trustworthy, it is not necessary to depend on outside authorities to say what is right”. Given these qualities of an authentic leader and the positive influence on PsyCap demonstrated in the present study and elsewhere (e.g., Youssef & Luthans, 2007), the impact and contribution of an authentic leader cannot be overemphasised.

PsyCap has emerged as an important construct and has been linked to a number of organisational outcomes. A recent meta-analysis has for instance revealed positive associations between PsyCap and employee well-being, as well as negative associations between PsyCap and job stress and anxiety (Avey, Reichard et al., 2011). Importantly, PsyCap is usually considered a malleable and open-to-development personal characteristic (Luthans et al., 2007). While there still is limited knowledge about how PsyCap is formed and relatively few studies address this issue, emerging research suggest that leadership perhaps plays an important role (Avey, Avolio, Luthans, 2011). As such, this study joins previous empirical research (e.g., Hystad et al., 2014) in demonstrating that authentic leaders possess the positive qualities needed to boost follower PsyCap.

Although the third and fourth hypotheses of the present study were not supported, our findings nevertheless paint a picture of a leader whose influence is not restricted to those working closely with her, but transcends to everyone at the workplace. Since the organisation is regarded as one entity, the leader's influence ought to be perceived likewise by every employee for that influence to be meaningful, productive, and effective. Having a leader that is perceived by some as more authentic and the rest as less authentic could create a sort of disparity in the degree of the leader's influence of the employees. Since more and more studies are supporting the notion that the authentic leader possesses the necessary qualities that could abate the effect of negative organisational variables like job insecurity and intentions to quit the organisation, it is therefore encouraging to find that such leaders’ influence (as discovered from the present study) is invariably perceived by the employees in the organisation as a whole.

Implications and LimitationsFindings from the present study support the model of authentic leadership (Avolio & Gardner, 2005; Avolio et al., 2004), and as purported by previous research, the notion that a leadership style like the authentic leadership is able to inspire positive behaviour among the employees (Hystad et al., 2014; Moriano, Molero, Lévy-Mangin, 2011; Walumbwa et al., 2008). This realisation calls for action on the part of consultants and drivers of change in organisations. Specifically, organisations should invest adequate mechanisms in ensuring that leaders internalised moral perspectives, relational transparency, as well as the other essential components of the authentic leadership construct. Furthermore, the characteristics of an authentic leader ought to be thoroughly considered during selection, training, and promotion. Scholars maintain that this will stimulate efficacy and a healthy and efficient work environment (Avolio & Gardner, 2005).

It is no longer new within social research that respondents are influenced by social desirability while responding to questions from a questionnaire (Donaldson & Grant-Vallone, 2002). Although participants in the present study were informed about their anonymity, it is still possible that some of the participants answered the questions with some amount of skepticism. Additionally, as it is endemic in social research, it is difficult to steer clear of self-serving bias, given the fact that our findings are based on employees’ assessment of their leader. Including other data collection methods (e.g., observation) would have provided us with more windows of opportunities to investigate the relationship between the authentic leader and the employees. But then again, the whole idea of the study was to probe employees’ perceptions of their leader.

Finally, the current study was conducted in a male dominated working environment, so this could have influenced the findings in the present paper. Additionally, the R-squared values for the variables are low but satisfactory, especially for the ‘job insecurity’ variable. Moreover, the fact that the present study was based on cross-sectional data makes it a difficult venture to draw causal claims. Since the data for this study was only collected at one time point, the associations between authentic leadership, job satisfaction, job insecurity, and intentions to quit (as well as the indirect relationship through PsyCap) might all be the results of the current situation at that particular time. The causal chain could for example be reversed, that is, employees who are already happy with their work might rate the captain higher. In relation to this, Antonakis and Day (2012) maintain that most leadership instruments suffer the problem of endogeneity. When employees are aware of leader outcome (an example is ‘how well the organisation has performed’, a question often associated with leadership effectiveness), asking these employees to rate their leader will often lead to them being biased in their ratings.

Future studies should endeavor to differentiate the specific role of an authentic leader from that of other positive leadership styles like transformational leadership, charismatic, transactional, and ethical leadership styles. This differentiation should also be extended to other types of leadership like the destructive and the laissez-faire leadership styles. This is important so as to differentiate an authentic leader from the rest of the existing leadership styles. More so, efforts could be centered on defining those leadership qualities found in other leadership styles that could easily coexist (or be incompatible) with authentic leadership style in the same leader.

ConclusionLeadership as a construct has had its fair share of focus and attention by scholars/researchers in recent years. Our results show–in line with previous research–that having a leader that is perceived as authentic is essential. Authentic leadership is not only important for the employees’ well-being, but also in developing employees’ PsyCap. Put together, these findings support Maxwell's (2007) assertion that how employees perceive their leader is pivotal for an organisation.

Conflict of InterestThe authors of this article declare no conflict of interest.

Financial SupportThis research was supported by the Norwegian Research Council's PETROMAKS (Grant No. 189521) and TRANSIKK (Grant No. 210494) programs.