Based on Schwartz's (1992, 1994) Human Values Theory and the Conservation of Resources Theory (Hobfoll, 1988, 1998, 2001), the present research sought to advance the understanding of Work-Family Balance antecedents by examining personal values and work engagement as predictors of Work-Family Conflict via their associations with perceived organizational climate and work burnout. The results of two studies supported the hypotheses, and indicated that perceived organizational climate mediated the relations between values of hedonism, self-direction, power, and achievement and Work-Family Conflict, and that work burnout mediated the relations between work engagement and Work-Family Conflict. Theoretical and practical implications regarding individual differences and experiences of Work-Family Balance are discussed.

Siguiendo la Teoría de los Valores Humanos (Schwartz, 1992, 1994) y la de la Conservación de Recursos (Hobfoll, 1988, 1998, 2001), este trabajo pretende avanzar en el conocimiento de los antecedentes del equilibrio trabajo-familia mediante el análisis de los valores personales y la implicación en el trabajo como predictores del conflicto trabajo-familia a través de su asociación con la percepción del clima organizacional y el agotamiento emocional en el trabajo. Los resultados de dos estudios respaldan las hipótesis, indicando que la percepción del clima organizacional mediatiza la relación entre valores de hedonismo, autodirección, poder y logro y conflicto trabajo-familia y que el agotamiento emocional en el trabajo mediatiza la relación entre implicación laboral y conflicto trabajo-familia. Se comentan las implicaciones teóricas y prácticas relativas a las diferencias individuales y experiencias del equilibrio trabajo-familia.

Past research has shown that work may interfere with the family and that the family may interfere with work (e.g., Amstad, Meier, Fasel, Elfring, & Semmer, 2011; Frone, 2000; Judge, Ilies, & Scott, 2006). The present paper purports to make several contributions to advancing the understanding of Work-Family Balance (WFB) antecedents by clarifying the relationships between employees’ values and work engagement, and Work-Family Conflict (WFC). First, we assessed the way personal values predict WFC, while examining whether values affect the favorableness of employees’ perceptions of organizational climate and subsequent experiences of WFC. Second, we explored the contribution of employees’ work engagement via its influences on work burnout (for the overall research model see Figure 1).

Work-Family Conflict (WFC) refers to an employee's experience that his or her work pressures or efforts to optimize job requirements interfere with the ability to meet family demands (Frone, 2000; Judge et al., 2006), also addressed as work interference with family (WIF) and family interference with work (FIW) (Amstad et al., 2011). Work-Family Conflict is the term most commonly used in the literature to describe this phenomenon, although the trend today is to focus the discourse on Work-Family Balance rather than Conflict.

Recent meta-analyses of WFC pointed to several workplace and personal variables as its antecedent sources such as task variety, job autonomy, family-friendly organizational climate/policies, role conflict and ambiguity, role overload, time demands, job involvement, work centrality, organizational support, family-(un)supportive supervision, coworker support, individual internal locus of control, negative affect and neuroticism, family centrality, family social support, and family climate (Michel, Kotrba, Mitchelson, Clark, & Baltes, 2011). Moreover, gender differences were found, indicating that workplace factors such as shift work, job insecurity, and conflicts with coworkers or supervisor on the one hand and responsibility for housekeeping or caring for family members on the other hand were significant factors contributing to WFC among men. For women, physical demands, overtime work, commuting time to work, and having dependent children were main WFC engendering factors (Jansen, Kant, Kristensen, & Nijhuis, 2003).

Past research has recognized WFC as an important factor that affects not only employees’ well-being but also their employers’ (Kossek, Baltes, & Matthews, 2011; Lapierre et al., 2008), and has been demonstrated to have detrimental impact on diverse work-related outcomes such as burnout, fatigue, and need for recovery from work (Bacharach, Bamberger, & Conley, 1991; Kinnunen & Mauno, 1998), productivity, work performance, risk of accidents, interpersonal conflicts at work, turnover rates, marital satisfaction, and physical and mental health conditions (Allen, Herst, Bruck, & Sutton, 2000; Barnett, Raudenbush, Brennan, Pleck, & Marshall, 1995; Frone, 2000; Jansen et al., 2006; Judge et al., 2006). On the other hand, when WFC is reduced, employees exhibit greater job satisfaction, affective organizational commitment, less turnover intentions (Butts, Caspar, & Yang, 2013), and report greater family satisfaction as well as overall life satisfaction (Lapierre et al., 2008). Specifically relevant to the present work is the role of individual dispositions as predictors of work-family conflict. Examples of such personal factors are internal locus of control, negative affect, and neuroticism (Allen et al., 2012).

Following this line of research, the present investigation sought to shed further light on the role of individual psychological orientations in WFC, borrowing the personal values perspective along with the notion of work engagement. In other words, we aimed to examine whether employees’ values and work engagement may explain individual differences in the experiences of conflict and balance between workplace requirements and family pressures.

Personal ValuesA widely acknowledged theory of individual variables which has inspired a considerable number of studies is Schwartz's (1992, 1994) theory of ten basic human values: “openness to change” values (hedonism, stimulation, and self-direction), “conservation” values (conformity, tradition, and security), “self-transcendence” values (universalism and benevolence), and “self-enhancement” values (achievement and power). The basic values explain individual decision-making, attitudes, and behavior, defined as beliefs charged with affect, and reflect desirable goals unspecified to certain contexts or actions, function as personal standards, and are ordered by importance relative to one another (Schwartz, 2012). According to Schwartz, the ten values are universal values, and yet individuals and groups may differ in the relative importance they attribute to them. Furthermore, given the different psychological meaning of the ten values, some of them conflict with one another (e.g., benevolence and power), whereas others are compatible (e.g., conformity and security) (Schwartz, 1992, 2006, 2012). Schwartz's values were found to have implications on various organizational factors such as citizenship behaviors directed toward individuals (OCB-I) and toward the group (OCB-O) (Arthaud-Day, Rode, & Turnley, 2012; Seppälä, Lipponen, Bardi, & Pirttilä-Backman, 2012), preferences for transformational and transactional leadership behaviors (Fein, Vasiliu, & Tziner, 2011), perceptions of relational-type contracts (Cohen, 2012), and workplace commitment (Cohen, 2011). Past research has indicated that values should be considered when examining experienced work-family conflict (Carlson & Kacmar, 2000; Smelser, 1998), as they may explain why certain individuals are more prone to experience WFC while others, in similar circumstances, are not. For example, materialistic values were found to be related to higher work-family conflict (Promislo, Deckop, Giacalone, & Jurkiewicz, 2010), and high WFC was found among employees characterized by “obsessive passion” towards work (Caudroit, Boiche, Stephan, Le Scanff, & Trouilloud, 2011).

In the present research, we referred to Schwartz's (1992, 1994) basic human values. We addressed these values as psychological pre-dispositions that may increase the potential to experience work-family conflict. Specifically, we predicted that given the psychological meaning embedded in the different values, personal values which are egocentric and indicative of willingness to achieve-openness to change and self-enhancement values (i.e., hedonism, stimulation, self-direction, power, and achievement) would be especially relevant to WFC, as such values may be expressed in willingness to excel and remain in control of both work and family demands. Specifically, following past research on positive relations between materialistic values and increased passion towards work and WFC (e.g., Caudroit et al., 2011; Promislo et al., 2010), we expected that these values would positively predict WFC. Accordingly, we hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 1. There will be a significant positive relation between personal egocentric values and WFC: employees characterized by high levels of hedonism, stimulation, self-direction, power, and achievement personal values will express higher level of WFC relatively to those characterized by low levels of these values. Values of conformity, tradition, security, universalism, and benevolence will be less related to WFC.

Organizational ClimateIt is reasonable to assume that personal values do not affect work-family balance in isolation of organizational perceptions. Recent meta-analyses indicated that organizational variables indicative of the support given to the employees, such as managerial support and perceived organizational work-family support, have clear relations with work-family conflict. The reports of WFC are lower when the employees perceive that their organization cares about reducing work-family conflicts and supports the ability to balance work and family demands (Kossek, Pichler, Bodner, & Hammer, 2011). Similarly, additional characteristic that we considered relevant to employees’ experience of work-family balance is the overall organizational environment or “organizational climate”. Organizational climate concerns employees’ perceptions of the social climate in a workplace, relevant to its policies, practices, and procedures (Schneider, 2000; Schulte, Ostroff, & Kinicki, 2006), and therefore a multidimensional impression the employees form of their workplace which reflects their impressions of the behaviors that are expected and rewarded (Armstrong, 2003; Zohar and Luria, 2005). Specifically, Litwin and Stringer (1968) differentiated between nine dimensions of organizational climate: (1) structure - employees’ feelings about the organizational constraints, amount of rules, regulations, and procedures; (2) responsibility - employees’ feelings such as “being your own boss” and not having to double-check personal decisions; (3) reward - employees’ feelings that the organization emphasizes positive rewards rather than punishments, and the perceived fairness of promotion policies; (4) risk - employees’ feelings about riskiness or challenge in the job/organization; (5) warmth - feelings of general good fellowship at the workplace, and the prevalence of friendly and informal social groups; (6) support - the perceived helpfulness of managers and other employees, and emphasis on mutual support; (7) standards - the perceived importance of implicit and explicit goals, and performance standards; (8) conflict - the feeling that managers and other workers are open to different opinions, and emphasis is placed on getting problems out in the open rather than ignoring them; and (9) identity - employees’ feelings that they belong to the organization and that they are valuable members of a working team.

Each of these dimensions, as well as an overall impression of organizational climate, may have immediate influence on employees’ experiences of the ability to balance between work and family requirements. For example, organizational climate perceptions were found to affect employees’ levels of stress, job satisfaction, commitment, and performance, which, in turn, have implications for productivity (Ostroff, Kinicki, & Tamkins, 2003; Schulte et al., 2006). The “support” dimension, i.e., supervisor support and organization support, were found to be related to work-to-family conflict (Carlson & Perrewé, 1999; Kossek, Pichler et al., 2011; Van Der Pompe & Heus, 1993), and relations were found between employees’ shared perceptions of an organization's value and work-family support and diminished WFC (Major, Fletcher, Davis, & Germano, 2008). Following this line of findings, in the present research we drew on the assumption that negative organizational climate perceptions reflected in lower job satisfaction, lower productivity, and lower perceptions of organizational support may raise employees’ dissatisfaction with their functioning at work, increasing the tension between work and family, as they strive to fulfill both work and family demands. Therefore, in the present research we predicted that perceived organizational climate would be associated with employees’ experiences of work-family conflict and/or balance.

Hypothesis 2. There will be a negative relation between the favorability of perceived organizational climate and WFC: employees characterized by unfavorable perceptions of organizational climate will express higher level of WFC relatively to those characterized by favorable organizational climate perceptions.

Moreover, we assumed that perceptions of organizational climate would be initially affected by employees’ personal values. As employees’ values were found to affect their perceptions of different organizational factors (e.g., perceptions of relational-type contracts and workplace commitment; Cohen, 2011, 2012) we expected to find that the values would also affect overall perceptions of organizational climate. Specifically, we assumed that organizational climate components – constraints, rules, regulations, procedures, challenges, and goals, as well as rewards, relations with co-workers, and feelings of belonging to the organization, might be affected by a high level of egocentric personal values emphasizing ambition and personal good. We predicted that this influence would be negative, supposing that such values may increase the employee's criticism of organizational practices and environment. In sum, in the present research, personal values categorized in Schwartz's (1992, 1994, 2012) conceptualization as “openness to change” and “self-enhancement” values were predicted to be indirectly related to work-family conflict via perceived organizational climate:

Hypothesis 3. There will be a negative relation between personal egocentric values and the favorability of perceived organizational climate: high levels of hedonism, stimulation, self-direction, power, and achievement will be associated with unfavorable perceptions of organizational climate.

Hypothesis 4. Perceptions of organizational climate will mediate the relations between the level of personal values and WFC.

Work EngagementAs mentioned earlier, along with predispositions derived from personal values and perceived organizational climate, in the present research we were also interested in exploring the influences of daily workplace experiences relevant to employees’ functioning, specifically the degree of investment in the workplace (i.e., “work engagement”), and whether these influences on WFC are mediated by burnout (see Figure 1).

Work or job engagement may be defined as “a positive, fulfilling, work related state of mind that is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption” (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004, pp. 295). In other words, work engagement reflects the willingness to invest effort in work and to persist in spite of difficulties (addressed as “vigor”); a sense of significance, enthusiasm, inspiration, pride, and challenge (“dedication”); and concentration and engrossment in work (“absorption”) (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004). Employees characterized by high work engagement are said to identify with their work, and to perceive their work as meaningful, inspirational, and challenging (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007). Past research has shown that “engaged employees” tend to experience high personal initiative, active approach, and motivation to acquire knowledge (Schaufeli & Salanova, 2007; Sonnentag, 2003), and that this engagement may amplify employees’ performance and organizational success in general (Bates, 2004; Baumruk, 2004; Demerouti & Cropanzano, 2010; Richman, 2006).

However, work engagement was also found to have negative consequences. Especially relevant to the present study are its effects on WFB – high work engagement was found to be associated with higher levels of work-family conflict due to the increased resources that engaged employees invest in their work, such as organizational citizenship behaviors (Halbesleben, Harvey, & Bolino, 2009). Drawing on the same rationale and theoretical background, in the present research we also predicted a negative effect of work engagement on WFC. Yet, we hypothesized different indirect influence of work engagement, namely, via excessive workplace burnout. We should note that there may be other possible variables which affect employees’ high job involvement, for example workaholism. Yet, workaholism has a different conceptual meaning as it is defined as “… the compulsion or the uncontrollable need to work incessantly” (Oates, 1971, p. 11), or an irresistible inner drive to work (McMillan, O’Driscoll, & Burke, 2003). Such definitions are said to exclude considering workaholism as a positive state (e.g., Schaufeli, Taris, & van Rhenen, 2008; Scott, Moore, & Miceli, 1997). Moreover, workaholism may initially imply that the balance between work and family does not exist or is interrupted as the balance is skewed towards work.

In the present research, we sought to look at allegedly “healthy” work involvement phenomena (i.e., work engagement) that similarly to personal values may also have negative implications for WFC. The theoretical background for the prediction of negative relations between work engagement, burnout, and WFC was the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, 1988, 1998, 2001). COR theory emphasizes people's willingness to acquire and protect resources (psychological, social, and material), while acquired resources are invested to obtain additional resources. The striving to obtain and protect resources is so important that psychological stress occurs when those are lost, threatened with loss, or if individuals cannot replenish resources after significant investment. Employees characterized by high work engagement are supposed to be preoccupied with reinvesting their resources in the workplace (knowledge, skills, energy, etc.). However, work demands threaten employees’ resources, and continued exposure to such demands leads to emotional exhaustion (Hobfoll & Freedy, 1993), especially as resource loss is disproportionately more salient than resource gain (Hobfoll, 2001). Eventually, such a state of affairs limits employees’ competence to meet family requirements, and therefore gives rise to experiences of work-family interference (see Halbesleben et al., 2009). Accordingly, we expected that though work engagement may lead to positive organizational consequences, it could also contribute to work family conflict.

Hypothesis 5. There will be a positive relation between work engagement and WFC: employees characterized by high levels of work engagement will express higher WFC relatively to those characterized by low levels of work engagement.

BurnoutThe experiences of psychological stress and emotional exhaustion following high and continued work engagement, consistent with the definition of “work burnout”. Work burnout is described along three dimensions: emotional exhaustion, experienced distance from others, and diminished personal accomplishment (Maslach, 1982). Burnout was addressed as the “dark side” of work engagement, leading employees to inferior job performance and sacrificing different aspects of personal life (Maslach, 2011). Work burnout has different negative outcomes for employees, such as absenteeism (Ahola et al., 2008), chronic work disability (Ahola, Toppinen-Tanner, Huuhtanan, Koskinen, & Väänänen, 2009), turnover (Shimizu, Feng, & Nagata, 2005), poorer job performance (Taris, 2006), working safety (Nahrgang, Morgeson, & Hofmann, 2011), and even depressive symptoms and decreased life dissatisfaction (Hakanen & Schaufeli, 2012). In the context of work-family balance, we expected that burnout would increase the perceived interference between work and family, particularly given its characteristic of emotional exhaustion (Johnson & Spector, 2007). Following COR theory, emotional exhaustion signals that the employee is deprived of his or her resources, and therefore may experience increased tension in an attempt to meet both work and family requirements. Accordingly, we predicted negative relations between work burnout and WFC. Finally, we hypothesized that as burnout may constitute the negative consequence of high work engagement, it should be assessed in the present research model as a mediator of the relations between work engagement and work-family conflict. In sum, our next hypotheses were as following:

Hypothesis 6. There will be a positive relation between burnout and WFC: the higher the experienced work burnout, the higher the reports of WFC will be.

Hypothesis 7. There will be a positive relation between work engagement and burnout: high work engagement will be associated with higher reports of work burnout.

Hypothesis 8. Work burnout will mediate the relations between work engagement and WFC.

The Present ResearchIn the present research, we aimed to examine two psychological paths to experiences of work-family conflict. First, we assessed the “I believe” path, i.e., the way personal values predict WFC, while exploring whether values affect employees’ perceptions of organizational climate and subsequently WFC (Study 1). Past research has highlighted the need to consider the factor of values in relation to work-family balance (e.g., Carlson & Kacmar, 2000; Promislo et al., 2010; Smelser, 1998), yet there is relatively little research on the association between personal values and WFC. Specifically, as far as we know, no previous research has examined the role of basic human values in predicting proneness to experience work-family conflict via their implications on employees’ perceptions of their workplace organizational climate. Second, we examined the “I invest” path, i.e., the influences of employees’ work engagement on WFC via its associations with work burnout (Study 2)1. Although past research has found that work engagement may be associated with high reports of WFC (Halbesleben et al., 2009), most of the studies tend to focus on the positive implications of work engagement. In the present research we intended to further explore work engagement associations with work-family conflict, while invoking the Conservation of Resources theory perspective as the rationale of our prediction that work burnout would mediate the relations between the two variables.

Study 1In this study, we aimed to explore the relations between personal values, perceived organizational climate and reports of WFC.

MethodParticipantsThe participants, who volunteered to take part in the study, were 242 employees of two company centers (one is more central as it includes the company's headquarters, the other is a big center) of a large cellular provider (129 women and 104 men, 9 participants did not indicate their gender; mean age=35.50, SD=1.07). The company provides services of wireless communications, owns and controls the elements necessary to sell, and deliver services to the end user including wireless network infrastructure, billing, customer care, marketing, and repair. Fifty-seven percent of the participants were single, 39% were married, and 4% were divorced. Forty-two percent of the participants stated that they were employed at the company's headquarters, 26% worked in the sales department, and 32% in the customer service department. Seventy-nine percent of them had a low occupational level, 17% were employed in intermediate management positions, and 4% indicated high managerial positions. As for level of education, 45% of the employees had a BA degree, 27% had a post-secondary education, 17% had a secondary education, and 11% indicated an MA degree.

Procedure and Measures2The participants signed up for a study examining, “issues regarding workplaces”. An experimenter explained that the study would involve answering questionnaires, and that the participants were expected to give honest answers representing their actual feelings and thoughts. All the participants took part in the study voluntarily, they were assured of complete anonymity (the participants did not provide any personal information), and were given the possibility to withdraw from filling the questionnaire at any time. The questionnaires took approximately 15minutes to complete. After completing the measures, all participants were debriefed. As we intended to assess the independent variables indicative of participants’ personal values and perceptions of organizational climate before addressing the dependent variable (i.e., experiences of work-family conflict), we first measured employees’ values and perceptions of organizational climate, and then the WFC measure was introduced.

Personal values. To assess their personal values, the participants were asked to complete a 57-item questionnaire representing 10 motivationally distinct value constructs on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (opposed to my values) to 9 (of supreme importance) (Schwartz, 1992): self-direction, 5 items, for example: “Think up new ideas and be creative” (Cronbach's alpha=.77, M=7.17, SD=1.13); stimulation, 5 items, for example: “Look for adventures and like to take risks” (Cronbach's alpha=.78, M=6.78, SD=1.23); hedonism, 6 items, for example: “Seek every chance I can to have fun” (Cronbach's alpha=.80, M=7.29, SD=1.16); conformity, 4 items, for example: “It is important to me always to behave properly” (Cronbach's alpha=.73, M=6.98, SD=1.36); security, 7 items, for example: “It is important to me to live in secure surroundings” (Cronbach's alpha=.70, M=6.57, SD=1.29); universalism, 8 items, for example: “It is important to me to listen to people who are different from me” (Cronbach's alpha=.80, M=7.16, SD=1.19); benevolence, 8 items, for example: “It is important to me to be loyal to my friends” (Cronbach's alpha=.85, M=7.15, SD=1.16); tradition, 5 items, for example: “Tradition is important to me” (Cronbach's alpha=.73, M=6.98, SD=1.36); power, 4 items, for example: “It is important to me to be in charge and tell others what to do” (Cronbach's alpha=.67, M=6.51, SD=1.31); and achievement, 5 items, for example: “Being very successful is important to me” (Cronbach's alpha=.85, M=7.53, SD=1.16).

Perceptions of organizational climate. We followed Vardi's (2001) implementation of a 38-item questionnaire based on the Organizational Climate Questionnaire (OCQ) (Litwin & Stringer, 1968), assessing nine dimensions of organizational climate. Responses were given on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree): structure, 5 items, for example: “The policies and organizational structure of the organization are clearly explained” (Cronbach's alpha=.76, M=4.36, SD=0.80); responsibility, 4 items, for example: “Our organizational philosophy emphasizes that people should solve their problems by themselves” (Cronbach's alpha=.68, M=2.76, SD=1.01); reward, 4 items, for example: “We have a promotion system here that helps the best man to rise to the top” (Cronbach's alpha=.74, M=3.709, SD=0.99); risk, 7 items, for example: “The philosophy of our management is that in the long run we get ahead fastest by playing it slow, safe, and sure” (Cronbach's alpha=.53, M=3.99, SD=0.73); warmth, 3 items, for example: “A friendly atmosphere prevails among the people in this organization” (Cronbach's alpha=.67, M=3.96, SD=1.06); support, 3 items, for example: “When I am on a difficult assignment I can usually count on getting assistance from my boss and co-workers” (Cronbach's alpha=.70, M=2.78, SD=1.18); standards, 4 items, for example: “In this organization we set very high standards for performance” (Cronbach's alpha=.58, M=4.38, SD=0.77); conflict, 4 items, for example: “Decisions in management meetings are made quickly and without any difficulty” (Cronbach's alpha=.38, M=3.82, SD=0.80); and identity, 4 items, for example: “People are proud to belong to this organization” (Cronbach's alpha=.59, M=3.25, SD=0.65).

Because of relatively low reliability coefficients of four dimensions (risk, standards, conflict, and identity), the items included in these dimensions were analyzed separately. In addition, according to the hypotheses, an overall measure of perceived organizational climate was computed (Cronbach's alpha=.74, M=2.98, SD=0.56).

Work-family conflict. Work-family conflict was measured with a scale developed by Netemeyer, Boles, and McMurrian (1996), consisting of 10 items to which participants responded on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Five items assessed work-family interference (e.g., “The demands of my work interfere with my home and family life”) and five items assessed family-work interference (e.g., “The demands of my family or spouse/partner interfere with work-related activities”). A recent meta-analysis has indicated that WIF and FIW are consistently related to the same types of outcomes while assessing both directions of the conflict (Amstad et al., 2011). Accordingly, as we aimed to assess the experience of a conflict in a sense of imbalance between work and family demands, an overall measure of WFC was computed (Cronbach's alpha=.89, M=2.80, SD=0.96).

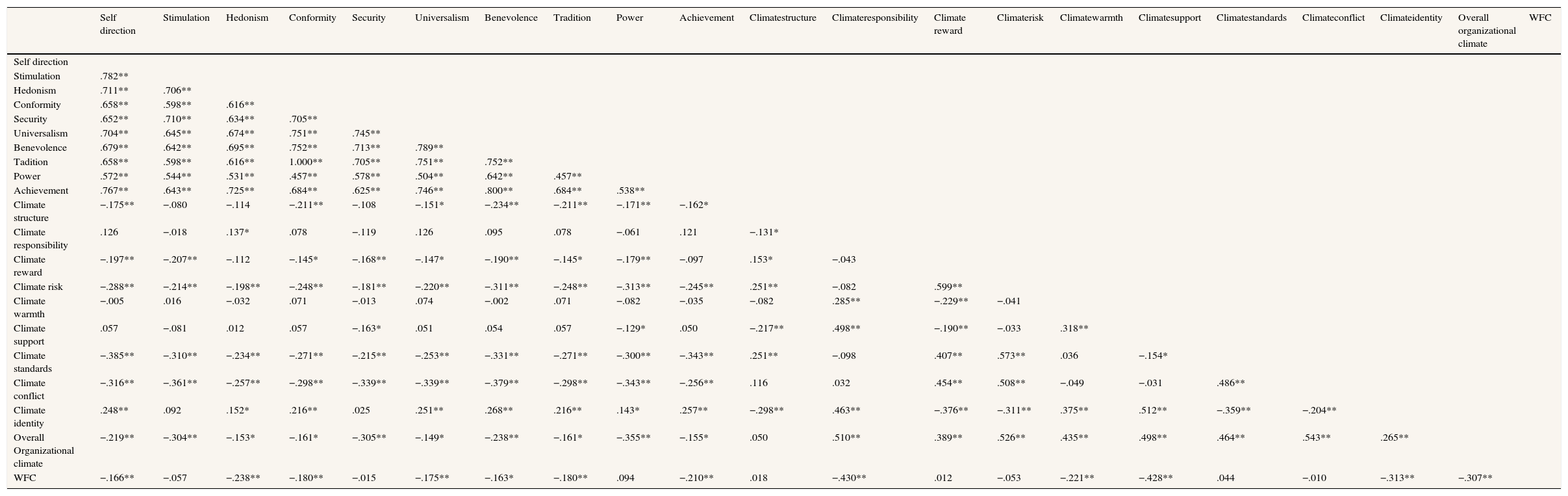

Results3In order to access the predicted mediated relationships between the variables, we followed Baron and Kenny, (1986) procedure for examining mediation4. The analyses lend support to Hypotheses 1-4, as follows (see Figure 2):

- (1)

WFC regressed on hedonism (the independent variable) and the overall measure of perceived organizational climate (the supposed mediator): hedonism appeared as a significant predictor of work-family conflict, β=.18, t(240)=2.79, p<.01; hedonism significantly predicted the perceived organizational climate, β=-.17, t(240)=-2.77, p<.01; and perceived organizational climate significantly predicted WFC while controlling for hedonism, β=-.43, t(239)=-7.66, R2=.22, p<.001. The Sobel test (see Soper, 2014) indicated that perceived organizational climate significantly mediated between hedonism and WFC (z=2.59, p<.01). Since the omission of perceived organizational climate from the model reduced but did not eliminate the influence of hedonism on WFC, the results represent a partial mediation effect.

- (2)

WFC regressed on achievement and the overall measure of perceived organizational climate: achievement appeared as a significant predictor of work-family conflict, β=.18, t(240)=2.91, p<.01; achievement significantly predicted the perceived organizational climate, β=-.16, t(240)=-2.47, p<.05; and perceived organizational climate significantly predicted WFC while controlling for achievement, β=-.42, t(239)=-7.60, R2=.22, p<.001. The Sobel test indicated that perceived organizational climate significantly mediated between achievement and WFC (z=2.35, p<.05). The omission of the mediator from the model pointed to partial mediation.

- (3)

WFC regressed on self-direction and the overall measure of perceived organizational climate: self-direction was a significant predictor of work-family conflict, β=.13, t(240)=1.87, p<.05; self-direction also significantly predicted the perceived organizational climate, β=-.21, t(240)=-3.28, p<.01; and perceived organizational climate significantly predicted WFC while controlling for self-direction, β=-.43, t(239)=-7.50, R2=.20, p<.001. The Sobel test indicated that perceived organizational climate significantly mediated between self-direction and WFC (z=2.90, p<.05). The omission of perceived organizational climate from the model indicated partial mediation.

- (4)

WFC regressed on power and the overall measure of perceived organizational climate: the results indicated close to significance effect of power on work-family conflict, β=.11, t(240)=1.80, p=.07; power significantly predicted the perceived organizational climate, β=-.36, t(240)=-6.01, p<.001; and perceived organizational climate significantly predicted WFC while controlling for power, β=-.40, t(239)=-6.47, R2=.16, p<.001. The Sobel test indicated that perceived organizational climate significantly mediated between power and WFC (z=4.36, p<.001). The omission of perceived organizational climate from the model indicated full mediation, as the effect of power on WFC was eliminated.

Additional analyses were performed in order to access mediation with specific dimensions and specific items (see Method section) of perceived organizational climate. WFC regressed on personal values, dimensions of structure, responsibility, reward, warmth, support, and items representing the dimensions of conflict, standards, risk, and identity. Significant relations appeared with values of self-direction and achievement, and the following: perceived organizational dimension of “structure”, organizational “standard” item (“There is much personal criticism in this organization”), and organizational “identity” item (“I feel little loyalty to this organization”).

As the regression coefficients between the mentioned personal values and WFC have already been presented, we turn to a short report of the coefficients between the IVs and the mediators, and between the mediators and the dependent variable:

- (5)

WFC regression on self-direction and the item of perceived criticism at the workplace: self-direction significantly predicted perceived criticism, β=.20, t(239)=3.21, p<.05; and perceived criticism significantly predicted WFC while controlling for self-direction, β=-.23, t(238)=-3.93, R2=.07, p<.001. The Sobel test indicated that perceived criticism significantly mediated between self-direction and WFC (z=2.30, p<.05). The omission of the mediator from the model indicated partial mediation.

- (6)

WFC regression on self-direction and the loyalty item: self-direction significantly predicted loyalty, β=.23, t(239)=3.64, p<.001; and loyalty significantly predicted WFC while controlling for self-direction, β=-.31, t(238)=-4.96, R2=.11, p<.001. The Sobel test indicated that loyalty significantly mediated between self-direction and WFC (z=2.96, p<.01). The omission of loyalty from the model indicated full mediation, as the effect of self-direction on WFC was eliminated.

- (7)

WFC regression on achievement and the loyalty item: achievement significantly predicted loyalty, β=.22, t(239)=3.56, p<.001; and loyalty significantly predicted WFC while controlling for achievement, β=-.30, t(238)=-4.75, R2=.12, p<.001. The Sobel test indicated that loyalty significantly mediated between achievement and WFC (z=2.92, p<.01). The omission of loyalty from the model indicated full mediation, as the effect of achievement on WFC was eliminated (Table 1).

Table 1.Study 1: Inter-correlational Matrix

Self direction Stimulation Hedonism Conformity Security Universalism Benevolence Tradition Power Achievement Climatestructure Climateresponsibility Climate reward Climaterisk Climatewarmth Climatesupport Climatestandards Climateconflict Climateidentity Overall organizational climate WFC Self direction Stimulation .782** Hedonism .711** .706** Conformity .658** .598** .616** Security .652** .710** .634** .705** Universalism .704** .645** .674** .751** .745** Benevolence .679** .642** .695** .752** .713** .789** Tadition .658** .598** .616** 1.000** .705** .751** .752** Power .572** .544** .531** .457** .578** .504** .642** .457** Achievement .767** .643** .725** .684** .625** .746** .800** .684** .538** Climate structure −.175** −.080 −.114 −.211** −.108 −.151* −.234** −.211** −.171** −.162* Climate responsibility .126 −.018 .137* .078 −.119 .126 .095 .078 −.061 .121 −.131* Climate reward −.197** −.207** −.112 −.145* −.168** −.147* −.190** −.145* −.179** −.097 .153* −.043 Climate risk −.288** −.214** −.198** −.248** −.181** −.220** −.311** −.248** −.313** −.245** .251** −.082 .599** Climate warmth −.005 .016 −.032 .071 −.013 .074 −.002 .071 −.082 −.035 −.082 .285** −.229** −.041 Climate support .057 −.081 .012 .057 −.163* .051 .054 .057 −.129* .050 −.217** .498** −.190** −.033 .318** Climate standards −.385** −.310** −.234** −.271** −.215** −.253** −.331** −.271** −.300** −.343** .251** −.098 .407** .573** .036 −.154* Climate conflict −.316** −.361** −.257** −.298** −.339** −.339** −.379** −.298** −.343** −.256** .116 .032 .454** .508** −.049 −.031 .486** Climate identity .248** .092 .152* .216** .025 .251** .268** .216** .143* .257** −.298** .463** −.376** −.311** .375** .512** −.359** −.204** Overall Organizational climate −.219** −.304** −.153* −.161* −.305** −.149* −.238** −.161* −.355** −.155* .050 .510** .389** .526** .435** .498** .464** .543** .265** WFC −.166** −.057 −.238** −.180** −.015 −.175** −.163* −.180** .094 −.210** .018 −.430** .012 −.053 −.221** −.428** .044 −.010 −.313** −.307** * p<.05, ** p<.01, *** p<.001.

We referred to the relationship of personal values and perceived organizational climate assessed in Study 1 as the “I believe” of WFC, i.e., psychological predispositions and perceptions of workplace environment that predict employees’ experiences of work-family conflict. After assessing these influences, Study 2 aimed to explore the “I invest” of WFC, which is the predictive potential of employees’ levels of work engagement and burnout.

MethodParticipantsThe participants, who volunteered to take part in the study, were 240 employees from two high-tech companies and one communications company (126 women, 114 men, mean age=34.68, SD=7.34). The high-tech companies specialize in the development of cutting-edge technologies and incorporate advanced computer electronics. The communication company provides customers with diverse technology-driven communication solutions, including long distance calls for fixed and mobile lines and Internet infrastructure. Twenty-five percent of the participants were single, and 75% were married. Seventy-eight percent of the employees were employed at non-managerial positions and 22% indicated managerial position. As for level of education, 56% of the employees had a BA degree, 22% indicated an MA degree, 19% had a post-secondary education, and 3% had a secondary education.

Procedure and MeasuresThe participants signed up for a study examining, “issues regarding workplaces”. An experimenter explained that the study would involve answering questionnaires, and that the participants were expected to give honest answers representing their actual feelings and thoughts. All the participants took part in the study voluntarily, they were assured of complete anonymity (the participants did not provide any personal information), and were given the possibility to withdraw from filling the questionnaire at any time. The questionnaires took approximately 10minutes to complete. After completing the measures, all participants were debriefed. We first measured employees’ work engagement and burnout, and then the WFC measure was introduced.

Work engagement. To assess work engagement, the participants were asked to complete a 9-item questionnaire (the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale - UWES; Schaufeli, Bakker, & Salanova, 2006). Responses were given on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree) reflecting three dimensions: dedication, 3 items, for example: “I am enthusiastic about my job” (Cronbach's alpha=.77, M=4.34, SD=1.45); vigor, 3 items, for example: “When I get up in the morning, I feel like going to work” (Cronbach's alpha=.81, M=4.72, SD=1.05); absorption, 3 items, for example: “I am immersed in my job” (Cronbach's alpha=.89, M=4.78, SD=0.96). As it is recommended to use the overall scale as a measure of work engagement (Schaufeli et al., 2006) and according to the present hypotheses, the overall UWES measure was used in the present study (Cronbach's alpha=.71, M=4.68, SD=0.94).

Burnout. Employees’ experiences of burnout were assessed by a 16-item questionnaire (Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Scale, MBI-GS; Schaufeli, Leiter, Maslach, & Jackson, 1996), that the participants answered on a 1 (never) to 6 (daily) Likert scale. The MBI-GS measures three dimensions of burnout: 5 items assessing exhaustion, e.g., “I feel used up at the end of the workday” (Cronbach's alpha=.85, M=4.51, SD=0.36); 5 items assessing cynicism, e.g., “I have become less enthusiastic about my work” (Cronbach's alpha=.75, M=4.68, SD=0.45); and 6 items assessing professional efficacy, e.g., “In my opinion, I am good at my job”, a reverse coded item (Cronbach's alpha=.67, M=4.64, SD=0.29). Burnout is reflected in higher scores on exhaustion and cynicism, and lower scores on efficacy. According to the hypotheses, an overall measure was computed (Cronbach's alpha=.88, M=4.62, SD=0.65).

Work-family conflict. Work-family conflict was measured with the same scale as in Study 1 (Netemeyer et al., 1996), 10 items to which participants responded on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Five items assessed work-family interference and five items assessed family-work interference. An overall measure was computed (Cronbach's alpha=.90, M=4.58, SD=0.84).

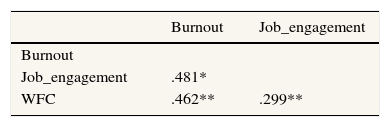

Results5In order to access the indirect influence of job engagement on WFC via experienced burnout, we followed Baron and Kenny, (1986) steps for assessing mediation. The results lend support to Hypotheses 5 - 8 (see Figure 3).

- (1)

WFC regression on job engagement (the independent variable) and burnout (the supposed mediator) indicated that job engagement was a significant predictor of work-family conflict, β=.17, t(238)=2.09, p<.01, so that high job engagement was associated with high WFC.

- (2)

Job engagement significantly predicted burnout, β=.48, t(238)=8.38, p<.001.

- (3)

Burnout significantly predicted WFC while controlling for job engagement, β=.44, t(237)=2.50, R2=.04, p<.001. The Sobel test revealed that burnout significantly mediated between job engagement and WFC (z=5.48, p<.001). The omission of burnout from the model indicated full mediation, as the effect of job engagement on WFC was eliminated. (Table 2).

The present research aimed to understand work-family balance antecedents by examining the indirect relations between employees’ values and work engagement, and WFC.

Study 1 explored the relations between employees’ personal values and perceived organizational climate, and their experiences of work-family conflict. We predicted that employees characterized by high levels of “openness to change” and “self-enhancement” values would express higher WFC than those characterized by low levels of these values, while values of conformity, tradition, security, universalism, and benevolence would be less related to WFC. This prediction was generally supported. Employees high in hedonism, self-direction, power, and achievement expressed high WFC. Contrary to the predicted influence of stimulation (one of the “openness to change” values), it did not predict WFC. The results also lend support to the indirect effect of personal values, as perceived organizational climate was found to mediate between personal values and WFC. High levels of hedonism, self-direction, power, and achievement were associated with low levels of perceived overall organizational climate, i.e., relatively unfavorable perceptions, and consequently high WFC. In addition, perceived criticism at the workplace and employee's organizational loyalty items appeared as mediators between values of self-direction and achievement, and WFC. Self-direction was positively associated with perceived criticism at the workplace and eventually high WFC. However, self-direction and achievement values were also positively related to organizational loyalty, whereas loyalty negatively predicted WFC.

Overall, the results point to associations between personal values and perceived organizational climate, and experiences of work-family conflict. First, it seems that high egocentric values relate to unfavorable climate perceptions. This may be due to increased criticism toward the work environment vis-à-vis personal aspirations. In other words, when high personal aspirations embedded in hedonism, self-direction, power, and achievement values are not met, the employee may perceive the existing organizational climate more negatively compared to one characterized by lower levels of these values. Study 1 did not indicate similar results with the “stimulation” value. This may be due to its specific psychological meaning and influence, since, although egocentric, this value deals with excitement and challenge, while other egocentric values emphasize prestige, control, independence, success, and pleasure (Schwartz, 1992, 1994). Therefore, the latter values have a greater potential to clash with organizational constraints and norms than “stimulation”.

Second, the results indicated that an unfavorably perceived organizational climate clearly relates to higher reports of work-family conflict. This influence may be due to the overall perception that one's organizational environment is less supportive than preferred, and therefore the conflict, namely, imbalance between work and family demands, is amplified. Interestingly, values of self-direction and achievement were positively related to organizational loyalty. This finding seems to contradict the hypothesized link between egocentric values and unfavorable organizational perceptions. It may be that employees’ perceptions of organizational loyalty are independent of other climate dimensions in the context of values’ implications; however, more research is required to clarify these relations. Yet, the consequential association between loyalty and WFC was in line with our predictions, as the negative relation between these variables indicates that lower loyalty (i.e., “unfavorable” perceptions) is associated with higher WFC.

Study 2 explored the second part of the proposed model (see Figure 1) by examining the relations between employees’ work engagement and burnout, and their experiences of work-family conflict. We hypothesized and found that employees who were highly engaged in their work expressed higher WFC. Moreover, the results supported the indirect influence of work engagement via work burnout – work engagement was positively associated with burnout that in turn positively predicted WFC. Overall, the results of Study 2 point to the detrimental effect of seemingly positive phenomena (i.e., employees’ effort). High levels of work investment may lead to burnout, and this state of emotional (and in some cases physical) exhaustion may amplify employees’ capability to balance work pressures and family demands.

The present research has several implications, both theoretical and practical. First, from a theoretical point of view, the two studies indicate that to understand work-family balance better, we should address important individual differences in psychological predispositions. Such predispositions are reflected in values, which form personal standards and affect attitudes and behavior. Past research has indicated that values may explain why certain individuals are more prone to experience WFC than others are (Carlson & Kacmar, 2000; Smelser, 1998). The present work followed this reasoning by assessing the effect of personal values via their associations with perceived organizational climate. While recent research has found relations between materialistic values and high work-family conflict (Promislo et al., 2010), the present results indicate the role of basic personal values, particularly egocentric values conceptualized by Schwartz as part of “self-enhancement” and “openness to change” orientations. High levels of these values (i.e., hedonism, achievement, self-direction, and power) may be associated with positive organizational outcomes. However, as the present research reveals, they may also lead to relatively negative perceptions of organizational climate. We suggested that the latter may be due to increased criticism toward the work environment that such values, indicative of willingness to excel and control, may encourage. However, future research is needed in order to clarify the psychological mechanism behind this association. Eventually, and in line with past research propositions (e.g., Carlson & Perrewé, 1999; Kossek, Baltes et al., 2011; Major et al., 2008; Van Der Pompe & Heus, 1993), perceived organizational climate projects on WFC, so that negative climate perceptions predict high experiences of work-family interference.

Other important individual differences are reflected in the degrees of work engagement and burnout. We followed the theoretical framework of COR theory to explain the influences of these variables on WFC. Recent research has already found high WFC among employees characterized by so-called “obsessive passion” towards work (Caudroit et al., 2011). The present research takes a further step in clarifying the negative side of work engagement by showing that initially positive organizational behavior may incur personal costs reflected in increased burnout and subsequently work-family conflict. A possible explanation of burnout influences lies in employees’ depleted resources (Taris, Schreurs, & Van Iersel-Van Silfhout, 2001; Wright & Cropanzano, 1998). The depletion of resources makes it difficult to meet both work and family demands, making the employee vulnerable to WFC experiences.

On the practical level, the present findings have several implications for organizational practitioners and leaders. (1) Although organizations value traits of self-direction and achievement, the present findings indicate that these traits may also relate to high experiences of work-family conflict. Therefore, it is important to raise leaders’ awareness and sensitivity to expressions of work-family balance, especially among ambitious employees. (2) Perceived organizational climate, perceived criticism at the workplace, and employee's organizational loyalty were found to mediate between personal values and WFC. Accordingly, organizations should be encouraged to take steps to strengthen positive impressions of the workplace among highly ambitious employees. (3) Although work engagement is another highly valued employee's characteristic, work engagement positively associates with burnout that in turn predicts higher experiences of work-family conflict. Organizations should be aware of the detrimental effect of employees’ efforts that may eventually amplify their incapability to balance between work pressures and family demands.

Limitations and Future DirectionsThere are some limitations to the present research. One of them are the mean levels of work engagement and burnout in Study 2 that were relatively high (4.68 and 4.62 on a 1-6 scale). This may be due to the organizational context of this study – the participants were mainly employees of high-tech companies. The high-tech sector is considered to be very demanding (Snir, Harpaz, & Ben-Baruch, 2009), and high-tech employees were found to extend their work hours (Sharone, 2004). Therefore, it is reasonable to expect reports of high work engagement and burnout. We do assume that the present findings are not unique to workplaces characterized by heavy investment of resources. However, future research should address the organizational context as an additional factor, by examining whether it may moderate the relations between work engagement, burnout, and WFC.

Another more general limitation of the present research is the correlative nature of the two studies. We implemented regression analyses to examine the proposed hypotheses, specifically in order to access mediation. This approach enabled us to examine the indirect influences of personal values and work engagement. Yet, it is important to recall that the correlative nature of the present studies does not allow for causal inferences.

In sum, the findings of the two studies show that work-family balance is, indeed, closely related to personal values and work engagement, and that these effects are accounted by their associations with perceived organizational climate and work burnout. Future research should clarify the psychological process by which values of hedonism, achievement, self-direction, and power impact perceived organizational climate, and why stimulation, although related along with hedonism and self-direction to the “openness to change” values, does not have similar influence. Finally, the organizational context (Tziner & Sharoni, 2014) is an additional variable that can be examined in future research as a possible moderator of relations between work engagement, burnout, and WFC.

Conflict of InterestThe authors of this article declare no conflict of interest.

The data for the present studies were collected during the years 2013-2014 in a large cellular provider company, two high-tech companies, and a communication company, as described in Study 1 & Study 2 Method sections.

As the present two studies explored personal beliefs indicated by individual values, perceptions of the workplace, and experiences of work-family conflict, the most suitable way to collect the data was employees’ self-reports. Past work addressed self-reports as clearly appropriate for accessing employees’ psychological variables since individuals are the ones who are aware of their perceptions. In addition, we used widely cited and thoroughly researched measures while deliberately assessing their reliability also in the present studies (also see Conway and Lance, 2010 for discussion on the self-report method).

Employees’ gender was assessed in the initial analysis. Neither main effects nor interactions with gender were found. Therefore, the results are presented for both female and male employees.

Concurrent with Hypothesis 1, values of security, benevolence, conformity, universalism, and tradition were not significantly associated with WFC, and therefore were not included in mediation analyses.

Employees’ gender was assessed in the initial analysis. Neither main effects nor interactions with gender were found. Therefore the results are presented for both female and male employees.