Sustainable development is a priority to the United Nations. Moreover, investment managers consider environmental, social and governance score as an important variable in portfolios selection. The fifth goal in the 2030 Agenda is gender equality. Besides, European countries have established gender quotas on corporate boards to reduce the gender gap. Empirical studies about the influence of women directors on the company's corporate social responsibility (CSR) presented mixed results, especially in developing countries. This article compares the influence of gender diversity on corporate boards on CSR performance in developed and emerging European markets. We apply a panel data methodology with fixed effects to examine the companies listed in the MSCI Europe and MSCI EM Europe indices from 2010 to 2019. The results show that gender diversity on the board of directors influences CSR performance positively, and this influence is greater in developed countries. Consequently, legislation should promote gender policies.

On 25 September 2015, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the 2030 Agenda, a set of 17 Sustainable Development Goals to achieve within the next 15 years, aiming to eradicate poverty, protect the planet and ensure prosperity for all. It is an opportunity for countries and their societies to embark on a new path to improve the lives of all citizens around the world. The goals range from eliminating poverty, education, and gender equality to the fight against climate change, environmental care, or our cities' design. To accomplish these targets, everyone must work together: Governments, the private sector and civil society.

The interest of companies in social and environmental problems has been growing since the 1990s when a series of international financial, environmental and social scandals occurred as a measure to control the reputational risk (Valls Martínez, 2019; Velte, 2017b). In this sense, it is usual that companies publish corporate social responsibility reports along with the financial statements as a way of being accountable for their environmental, social and governance (ESG) practices (Fernández-Gago et al., 2018; Sial et al., 2018).

Nowadays, CSR reporting has become a duty to meet the goals of Agenda 2030 (ElAlfy et al., 2020; Tsalis et al., 2020; Wichaisri & Sopadang, 2018) and to gain the confidence of the capital markets (Qu & Leung, 2006). In effect, the investment managers value positively high scores in ESG criteria. There are many sustainable market indices, such as the FTSE4Good index or the Dow Jones Sustainability Index (DJSI).

The board of directors is the main body of corporate governance and establishes the company's strategies (Pletzer et al., 2015). The relationship between the configuration of the firm board and the management strategies is currently an important issue of research. Especially, gender diversity is one of the main drivers or corporate policy (Amorelli & García-Sánchez, 2021; Terjesen et al., 2016). The importance of CSR is parallel in many countries with the legal regulation that states a gender quota on company boards. The percentage of women is crucial to the effectiveness of the board and the increase of sustainable strategies (Velte, 2017a).

Moreover, the fifth sustainable development goal is “Gender Equality”. Target 5.5 is: “Ensure women's full and effective participation and equal leadership opportunities at all levels of decision making in political, economic and public life”. In this sense, the European Commission proposed that member countries enacted laws to achieve equitable representation of both sexes on board of directors in the companies listed in the European stock exchanges (Isidro & Sobral, 2015). In effect, most countries have developed such guidelines, and the female presence has been growing during the last years (Valls Martínez & Cruz Rambaud, 2019; Valls Martínez et al., 2019). However, there is still an underestimation of women's ability to hold senior management positions (Mateos del Cabo et al., 2010), which translates into a gap in the gender composition on the board of directors since men continue to be the majority group.

Literature has analysed the relationship between the presence of women on corporate boards and the practices of CSR. Most studies found a positive influence of female directors on CSR performance (Dawar & Singh, 2016; Rao & Tilt, 2016; Velte, 2017a, 2017b). Only a reduced number of empirical works showed a negative or no relationship (Fauzi & Locke, 2012; Jhunjhunwala & Mishra, 2012; Kılıç & Kuzey, 2019; Stanwick & Stanwick, 1998). However, in the latter cases, the study was done years ago. Therefore, it is not reviewed or the sample corresponded to developing countries; so, the presence of women was deficient and, consequently, it was difficult for their influence to be significant. Furthermore, some studies determine a non-linear relationship and consider that a minimum number of women, usually three, is required to exert a positive influence on CSR performance, being the relationship between the two variables U-shaped (Bernardi & Threadgill, 2010; Fernandez-Feijoo et al., 2014; Liao et al., 2018).

However, some recent studies, which has been focused on European and American banks, from 2001 to 2016 (Birindelli et al., 2018), listed non-financial Spanish companies, from 2004 to 2014 (Pucheta-Martínez et al., 2019), and companies include in the S&P 500 and Euro Stoxx 300 indices (Valls Martínez et al., 2020), from 2015 to 2019, have concluded that the relationship is inverted U-shaped. Namely, the presence of women on corporate boards positively links to CSR performance to a limit beyond which their influence is negative. Accordingly, gender parity is the ideal situation.

On the other hand, there is a virtual absence of empirical studies on the similarities or differences between developed and developing countries regarding the impact that the recruitment of women on company boards of directors has on CSR. Namely, there is a gap in joint and comparative analysis.

The main objective of this study is to examine the effect of women on corporate boards on CSR performance in the developed and emerging European markets, considering ten years (2010-2019) and using the same methodology to obtain comparable results. Specifically, we use regression models with lagged dependent variable and panel data with fixed effects.

The present research contributes to the subsequent advances in the literature. First, it provides empirical evidence that gender diversity on the board of directors increases CSR performance in developed and emerging European markets. To do this, we consider a recent broad sample period (from 2010 to 2019), while previous studies use distant and, sometimes, shorter periods. Second, we compare the behaviour in developed and emerging markets, while previous studies consider individual or only developed countries. Since we use the same methodology, variables and period, our results show a consistent comparison. Third, we study the existence of a reasonable limit to women on company boards.

So far, previous studies have focused on demonstrating how the increased presence of women in management positions increases CSR. It is true that traditionally the number of women has been merely testimonial and, in general, reduced. Authors have thus claimed for the effective incorporation of women on boards of directors. However, as it has been made, this statement implies that companies should increase the number of women as much as possible, which would lead to a situation opposite to the traditional one, i.e. a weak presence of men. In this article, however, maximum diversity is evident, which leads to the search for parity between the two sexes. Accordingly, this article does not contrast a linear relationship but a quadratic relationship in the form of an inverted U-shape. Moreover, this work evidenced that in developing countries, gender diversity on corporate boards achieves maximum effectiveness at lower values.

The remainder of this article is as follows. Section 2 sets out the key aspects of the relationship between gender diversity on company boards and CSR performance, does a literature review and describes the theoretical framework to establish the research hypotheses. Section 3 describes the sample, variables and methodology used. In Section 4, we present the results. Finally, in Section 5, we discuss the results and raise the main conclusions from this research.

2Literature review and theoretical frameworkThe board of directors defines corporative governance strategies. Thus, the composition of the company's board is decisive in the establishment of CSR activities (Mason & Simmons, 2014). That is, the percentage of women directors can influence the social and environmental policies of companies. In effect, heterogeneous groups have broader perspectives and, therefore, are more effective in identifying problems and generating alternatives and innovative solutions, which result in competitive advantage (Bassett-Jones, 2005; Watson et al., 1993). In general, women have dissimilar ethical backgrounds to men (Fernández-Gago et al., 2018). Namely, both genders have different skills and experiences (Sial et al., 2018). In this sense, women are more risk-averse (Charness & Gneezy, 2012; Croson & Gneezy, 2009; Jianakoplos & Bernasek, 1998) and propose less aggressive investment strategies (Campbell & Mínguez-Vera, 2008).

Women exhibit higher emotional intelligence (Barrientos Báez et al., 2018), they value social aspects more and are more participatory, democratic and inclined to the welfare of others, as well as more philanthropic (Dawar & Singh, 2016; Francoeur et al., 2019; Gennari, 2018). Even previous literature states that women have upper moral scores than men and, therefore, they are more compliant with accounting, financial, social and environmentally ethical standards (Kyaw et al., 2017; Rao & Tilt, 2016; Sial et al., 2018). To sum up, women on the board of directors reduce corruption risk and promote more robust corporate governance procedures which consider a more comprehensive range of stakeholders (Bernardi & Threadgill, 2010). Accordingly, women are more oriented towards CSR (Cuadrado Ballesteros et al., 2015; Dawar & Singh, 2016).

Abundant theories have been alleged to justify the beneficial presence of women on corporate boards. All of them can be considered reasonable and realistic. It is usual to consider a multi-theoretical framework approach (Nicholson & Kiel, 2007) for comparative and integrative purposes (Valls Martínez & Cruz Rambaud, 2019).

Stakeholder agency theory (Hill & Jones, 1992) combines two traditional theories in management: agency theory and stakeholder theory. Agency theory (Jensen & Meckling, 1976) correlates corporate governance with transparency and accountability to prevent that managers act contrarily to the interest of shareholders. When there are more women on boards, female directors are more likely to increase audits and the company's responsibilities (Adams & Ferreira, 2009). Therefore, they can influence CSR performance (Liao et al., 2018). Stakeholder theory considers that the long-term survival of the companies depends on its ability to meet the expectations not only of shareholders but also of other stakeholders (customers, investors, employees, public authorities and the public in general) (Brown & Forster, 2013), both in economic and non-financial aspects (Freeman, 1984; Valls Martínez, 2019). In this sense, the women's characteristics and skills enhance CSR and the satisfaction of different stakeholders more than their male counterparts (Ibrahim & Angelidis, 1994). Therefore, since women on the board of directors are usually independent members (Francoeur et al., 2008), their presence decreases information asymmetry (Lofgren et al., 2002) and, therefore, the conflicts of interest between managers and stakeholders (Shankman, 1999). Additionally, their presence increases CSR and sustainable strategies, leading to an improvement in the company's reputation.

According to resource dependence theory (Hillman et al., 2000; Pfeffer, 1972), more sundry boards expand the possibilities of having wider connexions with lenders and investors. Thus, the company's capability to obtain the necessary resources to fulfil its social and environmental responsibility is higher.

As the literature shows, if we accept that men and women have different characteristics, we can also allude to human capital theory, which we can identify with upper echelons theory. According to this scheme, diverse boards benefit companies due to each member's individual and personal human capital (Isidro & Sobral, 2015). Effectively, managers differ in their knowledge, personal characteristics, habits, culture, emotions and beliefs, differentiating their decisions (Hambrick, 2007; Hambrick & Mason, 1984). Since women are more prone to social and environmental problems, gender diversity on the company's board promotes CSR performance.

We consider that the above theories explain sufficiently the positive relationship between women on corporate boards and CSR performance. Nevertheless, we believe that the two following theories are even more suitable to understand such a connection. In compliance with social role theory, also called self-schema theory (Konrad et al., 2000) or feminist caring theory (Liao et al., 2019), women and men are different by their education. They are gender roles deeply rooted that lead individuals to act according to the established expectations (Eagly, 2009; Gutek & Morasch, 1982; Mateos del Cabo et al., 2010). As states above, women are more sensitive to social problems and behave more altruistically than men because of their scales values (Bernardi & Threadgill, 2010; Eagly et al., 2003). They behave more ethically and are more willing to address stakeholders issues and implement CSR measures (Francoeur et al., 2019; Gennari, 2018).

Finally, legitimacy theory points out that a company's CSR actions reflect its moral legitimacy and, considering such kind of actions, stakeholders accept the company as a moral entity (Scherer & Palazzo, 2007). Therefore, companies can deliberately determine the extent of gender diverse composition of their board of directors by increasing their legitimacy or acceptance in the market. A mixed board, where men and women are equally considered, determines a company offering equal gender opportunities, which legitimizes the company (Gennari, 2018).

All of the above theories make a strong case for increasing the presence of women on boards of directors to reverse the traditional situation of an overwhelming majority of men. In management positions, statistics have demonstrated a real "glass ceiling" for women (World Economic Forum, 2019). However, people should not expect the reverse situation, i.e., a composition in which men are a bare minority. In such a case, although this has not been necessary so far since the actual situation is still unfavourable for women, some of the above theories could be argued for a greater male presence. In addition, the literature has shown that heterogeneous groups bring a broader set of skills, knowledge and experience, allowing for a broader analysis of problems (Francoeur et al., 2008). Thus, by proposing a wider variety of possible alternatives, the final decisions are more efficient and innovative (Pletzer et al., 2015; Rose, 2007). More complex problems are solved more effectively. Therefore, the company, the market and all stakeholders benefit from gender-diverse boards of directors.

On the other hand, some authors (Ali et al., 2014; Pucheta-Martínez et al., 2019) have alleged the social identity theory to counteract the positive effects of the increased presence of women on boards. According to this theory, male and female directors would divide the board into two categorical groups. Members of each group (in-group) would communicate with and support each other but would oppose the other group members (out-group) and would have a breakaway position with them. In this way, there would be a decrease in communication and an increase in conflicts between the two groups, resulting in a worsening of the CSR.

Literature has shown a wide array of empirical works that positively link women directors' higher presence with CSR performance. Table 1 shows 45 journal articles corresponding to the period 2013-2021, which can be considered a representative sample of the research conducted in this field. For each article, its authors, year of publication, main result related to gender and CSR, the methodology used and the journal in which it was published are described. Although some of these studies cover an international area (Kyaw et al., 2017; Valls Martínez et al., 2020), most of the empirical analyses refer to a single country, such as the United States (Boulouta, 2013; G Giannarakis, 2014; Giannarakis et al., 2014; Lu & Herremans, 2019), the United Kingdom (Al-Qahtani & Elgharbawy, 2020; Tingbani et al., 2020), Spain (Pucheta-Martínez et al., 2019; Ramon-Llorens et al., 2021; Valls Martínez et al., 2019), Italy (Furlotti et al., 2019; Harjoto & Rossi, 2019), Australia (Aslam et al., 2018; Hollindale et al., 2019), Germany (Dienes & Velte, 2016) or China (Liao et al., 2018; Liao et al., 2019).

Summary of research.

| Authors | Main results related to gender and CSR | Methodology | Journal |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Ramon-Llorens et al., 2021) | Women exert a positive influence on CSR when they join the board as expert advisors, but not when they do so as a continuation of their political career. | Generalized method of moments regressions | Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal |

| (Al-Qahtani & Elgharbawy, 2020) | Women on boardroom positively influence disclosure and management of greenhouse gas | Logistic regression | Journal of Enterprise Information Management |

| (Amorelli & García-Sánchez, 2020) | Companies with al least three women on the board positively influence CSR disclosure | Panel data regression | Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management |

| (Atif et al., 2020) | The proportion of female directors increases company sustainable investment | Two-stage least squares (Instrumental Variables) | Journal of Corporate Finance |

| (Beji et al., 2020) | Women on corporate boards is positively linked to human rights and corporate governance | Generalized method of moments regressions | Journal of Business Ethics |

| (García-Sánchez et al., 2020) | The influence of female directors on CSR is higher in companys located in stakeholder oriented countries | Logistic regression | Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management |

| (Orazalin & Baydauletov, 2020) | Female members on corporate board influence positively social and environmental performance | Fixed effects panel regression | Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management |

| (Pucheta-Martínez et al., 2020) | Women on board of directors improve CSR except if they represent banks or inssurance companies | Tobit regression | Sustainable Development |

| (Tingbani et al., 2020) | There is a positive relationship between women on boardroom and greenghouse gas voluntary disclosure | Fixed effects panel regression | Business Strategy and the Environment |

| (Uyar et al., 2020) | Female directors on the boardroom improve CSR | Fixed effects panel regression | Toursim Management Perspectives |

| (Valls Martínez et al., 2020) | Female directors positively influence CSR performance | OLS regression and fixed-effects analysis | Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management |

| (Zahid et al., 2020) | Women directors improve corporate sustainability disclosure | Ordinary Least Square regression | Journal of Cleaner Production |

| (Birindelli et al., 2018) | Gender balanced corporate boards influence positively on CSR performance | Fixed effects panel regression | Sustainability |

| (Campopiano et al., 2019) | Women on boardroom increases CSR engagement if they are not members of the controlling family | OLS regression | Journal of Cleaner Production |

| (Charumathi & Rahman, 2019) | The proportion of women on board of directors is positively related to climate change disclosure concerning to the carbon disclosure project | Multiple regression model | Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal |

| (Cruz et al., 2019) | Women directors increase corporate social performance | Random effects panel regression | Entrepreneurship. Theory and Practice |

| (Fernandez et al., 2019) | Women on corporate board influences more positively CSR in contexts that value their communal orientation | Two-stage least squares and random effects regression | Management Decision |

| (Francoeur et al., 2019) | Women on board of directors improve CSR dimensions related to less powerful stakeholders (environment, contractors and the community) | Fixed effects panel regression | Journal of Business Ethics |

| (Furlotti et al., 2019) | The implementation and disclosure of gender policies is improved by female chairperson but not by female CEO | Probit models | Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management |

| (García-Sánchez et al., 2019) | Women on boardroom disclose more balanced, comparable and reliable information on CSR | Generalized method of moments regressions | International Business Review |

| (Gulzar et al., 2019) | Women on boards of directors strengthens company's CSR commitment | OLS regression | Sustainability |

| (Harjoto & Rossi, 2019) | There is a positive relationship between female directors and CSR | Two-stage least squares (Instrumental Variables) | Journal of Business Research |

| (Hollindale et al., 2019) | Women directors favour higher quality of greenhouse gas emission disclosure | Tobit regression | Accounting and Finance |

| (Liao et al., 2019) | Women directors enhance companies' environmental innovation | OLS regression | Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management |

| (Lu & Herremans, 2019) | Female members on corporate boards enhance environmental performance scores initially in sensitive industries | Random effects panel regresion | Business Strategy and the Environment |

| (Pucheta-Martínez & Gallego-Álvarez, 2019) | The higher proportion of women on company boards enhance CSR disclosure | Tobit regression | Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management |

| (Pucheta-Martínez et al., 2019) | There is a positive relationship between women on corporate boards and CSR disclosure | Fixed effects panel regression | Sustainable Development |

| (Pucheta-Martínez et al., 2019) | Independent and institutional female directors increases CSR reporting up to a tipping point from which influences negatively | Fixed effects panel regression | Business Ethics: A European Review |

| (Valls Martínez et al., 2019) | Women on company board are positively related to CSR performance | Probit models with endogeneous regressors | Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management |

| (Yaseen et al., 2019) | There is a positive relathionship between the presence of women on boardroom and CSR | Fixed effects panel regression | Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal |

| (Aslam et al., 2018) | The number of female directors is positively associated with CSR disclosure | Multiple regression model | Journal of Managerial Sciences |

| (Liao et al., 2018) | Female members of company boards influence positively CSR assurance | Logistic regression | Journal of Business Ethics |

| (Ben-Amar et al., 2017) | The proportion of women on board of directors is positively linked to the voluntary climate change disclosure | Probit model with continuous endogenous regressors | Journal of Business Ethics |

| (Hossain et al., 2017) | There is a positive relathionship between women on boardroom and carbon disclosure information | Fixed effects panel regression | Social Responsibility Journal |

| (Kyaw et al., 2017) | Female members of corporate boards influence positively CSR and this influence is higher in emerging marckets | Fixed effects panel regression and instrumental variables | Corporate Governance |

| (Dienes & Velte, 2016) | Women on company board increases CSR reporting intensity | OLS regression | Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal |

| (Cuadrado Ballesteros et al., 2015) | Women directors lead to a higher social, economic and environmental responsibility | Tobit regression | Spanish Accounting Review |

| (Isidro & Sobral, 2015) | Women on board of directors positively influence the compliance with ethical and social rules | Simultaneous equation model | Journal of Business Ethics |

| (Martínez-Ferrero et al., 2015) | Women on corporate boards influence positively CSR | Tobit regression | Investigaciones Europeas de Dirección y Economía de la Empresa |

| (Setó-Pamies, 2015) | Women on boardroom have a positive influence on CSR | OLS regression | Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management |

| (Fernandez-Feijoo et al., 2014) | Companies with al least three women on the board have higher levels of CSR reporting | Hofstede's model | Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management |

| (Grigoris Giannarakis, 2014) | Women on board of directors have a positive effect on CSR disclosure | OLS regression | Social Responsibility Journal |

| (Giannarakis et al., 2014) | The proportion of female members on boardroom positively influence CSR disclosure | Fixed effects panel regression | Management Decision |

| (Boulouta, 2013) | Women on corporate board reinforce the positive practices of CSR and reduce the negatives ones | Generalized method of moments regressions and two-step system | Journal of Business Ethics |

| (Zhang et al., 2013) | The percentage of women on corporate board enhance CSR performance | Logistic regression | Journal of Business Ethics |

Indeed, a scarce number of works found a negative relationship. For example, studies performed in New Zealand (Fauzi & Locke, 2012), Malaysia (Darus et al., 2015), Turkey (Colakoglu et al., 2020) or Pakistan (Majeed et al., 2015; Naseem et al., 2017). It has to be taking into account that these cases correspond with developing countries, and we can find other studies with opposite results, i.e. where the relationship has been positive, as in Malaysia (Sundarasen et al., 2016), Turkey (Kılıç & Kuzey, 2019) and Pakistan (Khan et al., 2019). Finally, some works found no relationship (Glass et al., 2016; Manita et al., 2018; Post et al., 2011; Walls et al., 2012). Hence, since this analysis is not yet conclusive, we can affirm that it is necessary to implement more empirical analysis, especially in developing countries. Moreover, if we want to get homogeneous and comparable results with developed countries, the variables and methodology must be similar in both studies.

Based on the former arguments, we predict that higher gender diversity on the board of directors will improve the company's CSR performance. Hitherto, literature related the higher female presence on board of directors and CSR performance positively. In this case, the maximum percentage of women directors would impact the company's better responsible behaviour. However, we believe that an overwhelming majority of men is just as harmful as a large majority of women. Hence, the desirable situation would be a parity situation or, in other words, reaching a maximum gender diversity level. It is important to note that "gender diversity" on the board of directors has been interpreted in the literature as synonymous with a higher percentage of women. However, this meaning is not correct. Maximum diversity implies an equal share of men and women.

Accordingly, the relationship between the percentage of women in boardroom and CSR performance will be quadratic, with an inverted U-shape. The following research hypotheses have been constructed to contrast this theory:

Hypothesis 1 (H1)

In developed countries, gender diversity on the board of directors is positively related to company CSR performance.

Hypothesis 2 (H2)

In emerging markets, gender diversity on the board of directors is positively related to company CSR performance.

3Method3.1The datasetThis study considers the European companies included in the MSCI Europe (MSCI) and the MSCI Emerging Markets Europe (MSCI EM) indices, during the period of 10 years, from 2010 to 2019. We aim to compare the possible differences between developed and emerging countries in the European context to establish specific characteristics or similitudes. Europe is a geographical area of interest, broad and cohesive, because of its history, tradition and present. Both indices capture large and mid-cap companies, covering around 85% of the free-float market capitalization in the considered countries. MSCI Europe index has 436 constituents, and the MSCI Emerging Markets Europe index includes 62 constituents. The dataset was collected from the Bloomberg database, excluding those firms with missing data to assure the reliability of the research (Liao et al., 2019). The final sample included 8,535 observations in the MSCI index analysis and 646 in de MSCI EM index.

Table 2 describes the sample composition on a country basis, the percentage of women on the board of directors and the score assigned to each country by the Global Gender Gap Report (World Economic Forum, 2019). It can be observed that the United Kingdom is the country with a higher weight in the MSCI sample since it has the 25.73% of companies, followed by Germany and France, with 12.14% and 11.41%, respectively. However, in the MSCI EM sample, Turkey has 29.41% of the total composition, followed by Poland and Russia, both of them with 25.88%. According to the Global Gender Gap Report 2020, developed countries are better ranked than developing countries. Effectively, the average ranking is 0.774 in developed countries and 0.694 in developing countries (it is essential to notice that the value ranges from 0 to 1). This fact is reflected in the percentage of women on company boards, since the average in developed countries is 27.93%, while in developing countries, it is only 13.47%. Thus, developed countries hire, on average, a higher percentage of women on board of directors than developing countries.

Sample composition by countries.

| Index | Country of Headquarters | Distribution of companies | Global Gender Gap Report 2020 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ranking | Score | % women on boards | |||

| MSCI Europe index | Austria | 1.76 % | 34 | 0.744 | 19.20 |

| Belgium | 2.80 % | 27 | 0.750 | 30.70 | |

| Denmark | 3.22 % | 14 | 0.782 | 30.30 | |

| Finland | 2.80 % | 3 | 0.832 | 32.80 | |

| France | 11.41 % | 15 | 0.781 | 43.40 | |

| Germany | 12.14 % | 10 | 0.787 | 31.90 | |

| Republic of Ireland | 1.97 % | 7 | 0.798 | 17.60 | |

| Italy | 5.81 % | 76 | 0.707 | 34.00 | |

| Luxembourg | 1.24 % | 51 | 0.725 | 12.00 | |

| Netherlands | 5.08 % | 38 | 0.736 | 29.50 | |

| Norway | 3.22 % | 2 | 0.842 | 42.10 | |

| Portugal | 0.83 % | 35 | 0.744 | 16.20 | |

| Spain | 5.29 % | 8 | 0.795 | 22.00 | |

| Sweden | 6.95 % | 4 | 0.820 | 36.30 | |

| Switzerland | 8.40 % | 18 | 0.779 | 21.30 | |

| United Kingdom | 25.73 % | 21 | 0.767 | 27.20 | |

| Others* | 1.35 % | - | - | - | |

| MSCI EM Europe index | Czech Republic | 4.71% | 78 | 0.706 | 14.50 |

| Greece | 10.59 % | 84 | 0.701 | 11.30 | |

| Hungary | 3.53 % | 105 | 0.677 | 14.50 | |

| Poland | 25.88 % | 40 | 0.736 | 20.10 | |

| Russia | 25.88 % | 81 | 0.706 | 7.00 | |

| Turkey | 29.41 % | 130 | 0.635 | 13.40 | |

Table 3 shows the percentage of companies and women on boards of directors by sectors in the considered time horizon. We observe that the percentage of women on the board of directors is similarly distributed in developed countries, ranging from 29.69% in the cyclical consumer sector to 27.84% in the energy sector. On the contrary, the dispersion is more remarkable in developing countries and, notably, its values are lower, since it ranges from 13.03% in the healthcare sector to 8.32% in the telecommunications sector.

Percentage of companies and women on boards by sector.

| MSCI Europe index | MSCI EM Europe index | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % companies | % women | % companies | % women | |

| Basic materials | 8.92 | 28.88 | 12.94 | 9.79 |

| Consumer cyclical | 15.25 | 29.69 | 11.76 | 9.71 |

| Consumer non-cyclical | 7.26 | 28.86 | 5.88 | 10.36 |

| Energy | 4.67 | 27.84 | 16.47 | 11.11 |

| Financials | 22.41 | 28.98 | 31.76 | 9.44 |

| Healthcare | 7.37 | 28.45 | 1.18 | 13.06 |

| Industrials | 20.75 | 28.49 | 4.71 | 8.96 |

| Technology | 6.22 | 28.82 | - | - |

| Telecommunications | 3.53 | 29.49 | 9.41 | 8.32 |

| Utilities | 3.63 | 28.91 | 5.88 | 9.76 |

Table 4 summarizes the variables used in this research and presents their definitions. The dependent variable is the ESG score index assigned by Bloomberg to each company, which ranges from 0.1 to 1 and jointly evaluates its environmental, social and governance performance. Investment managers consider this score an important indicator to decide the final composition of the portfolios, both particular and mutual funds. The Bloomberg database is used not only in real investment but also in market research. The ESG score is considered in previous literature as a proxy for measure the company's corporate social performance (Charumathi & Rahman, 2019; Giannarakis et al., 2014; Grigoris Giannarakis, 2014; Hossain et al., 2017; Manita et al., 2018; Miralles-Quirós et al., 2019; Valls Martínez et al., 2020).

Variables description.

| Abbreviation | Variable | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| ESGScore | ESG Score | ESG score assigned in Bloomberg database |

| PWomen | Women on board of directors | Percentage of women on board of directors |

| TobinQ | Tobin's Q | Stock price/replacement value |

| LnAssets | Company size | Logarithm of total assets |

| Indebted | Indebtedness | Total debt to total equity, percent |

| LnCO2Emis | LnCO2Emission | Logarithm of estimated total CO2 and CO2 equivalents emission in tonnes |

| PolEnergy | Policy Energy | Dummy variable, which takes the value 1 if the company apply policy energy efficiency and 0, otherwise |

| CrisisSystem | Crisis Management Systems | Dummy variable, which takes the value 1 if the company reports on crisis management systems or reputation disaster recovery plans to reduce or minimize the effects of reputation disasters and 0, otherwise |

| CSRAwards | Corporate Social Responsibility Awards | Dummy variable, which takes the value 1 if the company has received an award for its social, ethical, community or environmental activities or performance and 0, otherwise |

| CSRCommit | Corporate Social Responsibility Committee | Dummy variable, which takes the value 1 if the company has a CSR committee or team and 0, otherwise |

| Industry profile | Industry dummies | The considered sectors are: Basic Materials, Consumer Cyclical, Consumer non-Cyclical, Energy, Financials, Healthcare, Industrials, Technology, Telecommunications Services, Utilities |

The independent variable is the percentage of women on the board of directors (PWomen), defined as the number of women on the company board divided by the total number of board members. It reflects the gender diversity policy of each company at the level of managerial positions. Until now, most studies have been conducted on developed countries. The results show, in general, a positive and significant relationship between the female presence on the board of directors and the CSP. In this sense, we can mention some of them, in France (Yaseen et al., 2019), Germany (Dienes & Velte, 2016), Europe (Isidro & Sobral, 2015; Kyaw et al., 2017; Valls Martínez et al., 2020), Australia (Aslam et al., 2018), Canada (Ben-Amar et al., 2017), US (Boulouta, 2013; Francoeur et al., 2019) and China (Liao et al., 2019). However, the number of researches focusing on merging markets is scarce, and the results have not been entirely conclusive. For example, studies in India (Charumathi & Rahman, 2019), Pakistan (Khan et al., 2019) and Malaysia (Sundarasen et al., 2016) found a positive influence of women directors on CSP, but other works performed in Pakistan (Naseem et al., 2017) and Turkey (Colakoglu et al., 2020) found no relationship.

The control variables have been grouped as follows. There are three continuous financial variables: financial market performance, company size and indebtedness.

Financial performance can be identified with accounting or market measures. The first ones, ROE (return on equity) or ROA (return on assets), for instance, represent short-term financial performance since they are based on past events (Gentry & Shen, 2010). Moreover, their figures can be altered by companies, and we question their reliability in all cases. On the contrary, the second ones show the long-term value attributed by investors to the company based on their current situation and prospects (Haslam et al., 2010; Post & Byron, 2015). Specifically, we use Tobin's Q (TobinQ), which is the market-to-book value ratio (Huselid, 1995; Valls Martínez & Cruz Rambaud, 2019; Wiggins & Ruefli, 2002). It is an external value (Pletzer et al., 2015) not subject to the influence of taxes or accounting rules (Montgomery & Wernerfelt, 1988). Some studies find a positive influence of this variable on CSP (Ben-Amar et al., 2017; Hossain et al., 2017; Valls Martínez et al., 2019), but in other cases, there is a lack of relationship between the two variables (Francoeur et al., 2019).

The natural logarithm of the total assets (LnAssets) at the end of each considered year represents the company size. Bigger companies influence CSP positively for two reasons. These firms are more exposed to publish scrutiny and, consequently, disclose more information about their corporate responsibility initiatives. On the other hand, they dispose of more resources to invest in CSR practices (Grigoris Giannarakis, 2014). In this sense, a good number of previous research found a positive link between size and CSP (Aslam et al., 2018; Ben-Amar et al., 2017; Grigoris Giannarakis, 2014; Kyaw et al., 2017; Liao et al., 2019; Sial et al., 2018). Only a few research found a negative relationship (Dienes & Velte, 2016; Hou, 2019). Finally, there are even some articles where the results are mixed, depending on the considered model (Francoeur et al., 2019; Valls Martínez et al., 2020).

The total debt to total equity is the indebtedness ratio (Indebted). The implementation and disclosure of CSR practices require investment, i.e. funds. Theoretically, the relationship between indebtedness and CSP will be negative, such as is confirmed in previous literature, but not always significantly (Aslam et al., 2018; Ben-Amar et al., 2017; Dienes & Velte, 2016; Giannarakis et al., 2014; Grigoris Giannarakis, 2014; Hou, 2019; Sial et al., 2018). Namely, if the company has a high indebtedness, it will have few resources to invest in CSR (Andrikopoulos & Kriklani, 2013). Similarly, if the indebtedness is low, companies will be able to spend more money on social and environmental practices (Brammer & Pavelin, 2008). Nevertheless, there exist a large number of empirical researches where this kind of relationship is negative or positive, according to the model used (Boulouta, 2013; Kyaw et al., 2017; Prado-Lorenzo et al., 2012; Valls Martínez et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2013).

Moreover, we use five variables indicative of corporate social responsibility: the CO2 emissions, a continuous variable, and four dummy variables, which represent, respectively, the existence of policy energy, crisis management systems, corporate social responsibility awards and corporate social responsibility committee.

The logarithm of the estimated emission of carbon dioxide (CO2), methane and nitrous oxide in tonnes (LnCO2Emis) has been used in previous studies (Giannarakis et al., 2014; Valls Martínez et al., 2020) as an important measure of the air pollution due to the company's activities. After the sign of the Kyoto Protocol in 2005, most developed countries committed themselves to reduce the environmental impact of their industry by taking the necessary measures and policies to ensure that companies counteract the harmful effects of their emissions. Therefore, according to legitimacy theory, when such actions are indeed implemented, it is expected a positive relationship between the CO2 emissions and the CSP (Charumathi & Rahman, 2019; Dragomir, 2010; Gonzalez-Gonzalez & Zamora Ramírez, 2016). If this relationship were inverse, companies would not be complying with their CSR (Delmas & Blass, 2010; Freedman & Jaggi, 2011).

We also consider as a key indicator if the company has an efficient energy policy (PolEnergy); the company reports on crisis management systems or reputation disaster recovery plans to reduce or minimize the effects of reputation disasters (CrisisSystem); the company has received an award for its social, ethical, community or environmental activities or performance (CSRAwards); and, finally, if the company has a CSR committee or team (CSRCommit) (Isidro & Sobral, 2015; Valls Martínez et al., 2020).

In the end, dummies variables have been used to control the ten different industry profiles since social pressures and legal rules force industries more environmentally sensitive to carry out responsible policies to mitigate the damage caused by their activities (Galani et al., 2012; Grigoris Giannarakis & Litinas, 2011; Valls Martínez & Cruz Rambaud, 2019).

3.3MethodologyWe applied four econometric models in the two empirical studies developed: MSCI Europe index (a) and MSCI EM Europe index (b). First, Models 1a and 1b represent an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression by including the independent and control variables to explain the dependent variable, in line with previous literature (Bear et al., 2010; Bernardi & Threadgill, 2010; Martínez-Ferrero et al., 2015; Reverte, 2009).

Second, Models 2a and 2b added the quadratic term of the independent variable to investigate if the relationship between CSP and the percentage of women on the board of directors was nonlinear. Until now, we had found several studies that affirm a U-shaped relationship, which implies that there is a critical mass, namely, a minimum percentage of women necessary to influence positively on CSP (Amorelli & García-Sánchez, 2020; Fernandez-Feijoo et al., 2014). However, we wanted to check if the existence of a majority number of women is as undesirable as a majority of male representation, in which case the curve would be inverted U-shaped (Valls Martínez et al., 2020).

Third, Models 3a and 3b added the lagged dependent variable (1 lag) as an independent variable to control possible endogeneity and reverse causality problems since CSP and the percentage of female directors might influence each other (Francoeur et al., 2019; Valls Martínez et al., 2020).

Fourth, in Models 4a and 4b, we applied panel data methodology to monitor omitted variables and overcome unobservable heterogeneity in the empirical analysis (Boulouta, 2013; Miralles-Quiros, Miralles-Quiros & Guia Arraiano, 2017, 2017b). Hausman test was implemented to check if the model of fixed effects estimation, appropriate when the unobservable heterogeneity between the individuals is correlated with the regressors, represented the most consistent estimators or, otherwise, the model of random effects estimation should be applied (Campbell & Mínguez-Vera, 2008). Moreover, the Lagrange multiplier test was used to determine if the fixed effects model provided better results than the pooled linear regression (Breusch & Pagan, 1980). The methodology used is sufficiently contrasted in empirical studies in this line of research, as shown in Table 1.

Moreover, we compared all the models with the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC). In both criteria, the smaller value shows the better model. Furthermore, as usual, we tested the goodness of fit for each model with the F-statistic, a measure of the joint significance of regressors, and the adjusted R2, which indicates the proportion of variation of the dependent variable explained by the explanatory variables.

Finally, in Models 5a and 5b, and with a purely exploratory intention, since there is no previous evidence, we tested the interaction effects of both company size and CO2 emission with gender, applying OLS regression with quadratic effect and lagged variable. Similarly, in Models 6a and 6b with panel data methodology.

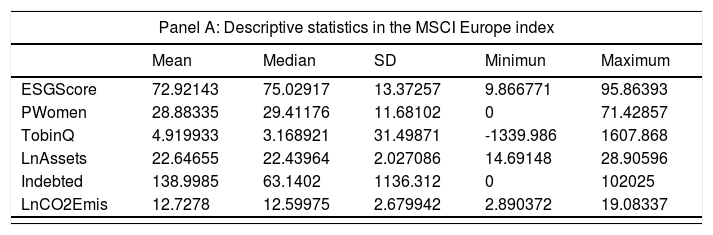

4Results4.1Descriptive statistics and correlationsTable 5 shows the main descriptive statistics for continuous variables in the sample period for the MSCI Europe index (Panel A) and the MSCI EM Europe index (Panel B). We can observe that the mean of the ESG Score is noticeably higher in developing countries than in emerging markets, while the standard deviation is below. That is, developed countries implement more practices of CSR than emerging markets. Besides that, the mean percentage of women on corporate boards is over three times in developing countries than in emerging markets. Likewise, the median is over four times. These figures are in line with the Global Gender Gap Report 2020 (World Economic Forum, 2019), which we reflected in Table 2 and commented on in Section 3.1 of this article. Tobin's Q value difference between the two samples is striking, indicating how developed countries value companies far above their book value while emerging markets value them below. Likewise, indebtedness is almost 44% higher in developed countries.

Continuous variables: Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations.

| Panel A: Descriptive statistics in the MSCI Europe index | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | SD | Minimun | Maximum | |

| ESGScore | 72.92143 | 75.02917 | 13.37257 | 9.866771 | 95.86393 |

| PWomen | 28.88335 | 29.41176 | 11.68102 | 0 | 71.42857 |

| TobinQ | 4.919933 | 3.168921 | 31.49871 | -1339.986 | 1607.868 |

| LnAssets | 22.64655 | 22.43964 | 2.027086 | 14.69148 | 28.90596 |

| Indebted | 138.9985 | 63.1402 | 1136.312 | 0 | 102025 |

| LnCO2Emis | 12.7278 | 12.59975 | 2.679942 | 2.890372 | 19.08337 |

| Panel B: Descriptive statistics in the MSCI EM Europe index | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | SD | Minimun | Maximum | |

| ESGScore | 58.96837 | 61.07487 | 15.43498 | 12.50594 | 90.45249 |

| PWomen | 9.791891 | 7.692308 | 11.46108 | 0 | 44.44444 |

| TobinQ | 0.908597 | 0.645068 | 1.008806 | 0.002403 | 8.625501 |

| LnAssets | 25.03994 | 24.84373 | 2.434566 | 20.12747 | 31.07136 |

| Indebted | 96.77562 | 56.29021 | 244.4143 | 0 | 5291.243 |

| LnCO2Emis | 13.52283 | 13.52835 | 2.995749 | 0.693147 | 18.74692 |

| Panel C: Pearson correlations in the MSCI Europe index | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESGScore | PWomen | TobinQ | LnAssets | Indebted | |

| ESGScore | 1.000 | ||||

| PWomen | 0.1896⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | 1.0000 | |||

| TobinQ | 0.0007(0.9450) | 0.0049(0.6487) | 1.0000 | ||

| LnAssets | 0.2137⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | 0.0576⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | -0.1137⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | 1.0000 | |

| Indebted | 0.0189⁎⁎(0.0815) | 0.0034(0.7560) | 0.3358⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | 0.1967⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | 1.0000 |

| LnCO2Emis | 0.3522⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | -0.0579⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | -0.0051(0.6347) | 0.1737⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | 0.0229⁎⁎(0.0347) |

| Panel D: Pearson correlations in the MSCI EM Europe index | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESGScore | PWomen | TobinQ | LnAssets | Indebted | |

| ESGScore | 1.000 | ||||

| PWomen | 0.0626(0.1119) | 1.0000 | |||

| TobinQ | -0.0334(0.3966) | -0.0119(0.7618) | 1.0000 | ||

| LnAssets | 0.0605(0.1248) | -0.0199(0.6133) | -0.5683⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | 1.0000 | |

| Indebted | 0.0402(0.3071) | −0.0042(0.9161) | -0.0342(0.3861) | 0.0985⁎⁎(0.0122) | 1.0000 |

| LnCO2Emis | 0.0071(0.8562) | −0.2258⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | -0.0437(0.2676) | 0.2290⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | -0.0221(0.5756) |

⁎⁎⁎, ⁎⁎ and * indicate less than 1% significance level, less than 5% and less than 10%, respectively.

Number of observations = 8,535 in the MSCI index and 646 in the MSCI EM index.

Panels C and D present the correlation analysis in the MSCI Europe index and MSCI EM Europe index, respectively. Both of them show a positive relationship between the dependent and independent variables, but in the developed countries is at the highest level of significance, while in emerging markets is not significant. Since we want to test not a linear but a quadratic relationship, it is plausible that the correlation is not significant, and the relationship, however, is verified. Analogously, company size, indebtedness and CO2 emissions show a positive correlation with ESG Score, very significantly in developed countries and not significant in emerging markets. However, Tobin's Q shows a different sign in the two samples, i.e. it is positively correlated in the MSC Europe index and negatively in the emerging countries. It is not significant in both markets.

Table 6 shows the t-test of the difference of means and the analysis of variance (ANOVA) performed to test the significance of the dummy control variables on the dependent variable. All variables are significant at the highest level. From its part, Panel A indicates that in the sample of the MSCI Europe index, the existence of a CSR committee is the most influential variable, while in the sample of MSCI EM Europe index is CSR awards. In both markets, the least influential variable is the existence of crisis management systems.

Dummy variables: Differences of means in the value of the explanatory variables and ANOVA test.

| Panel A: MSCI Europe index | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference of means test (t-test) | ANOVA test | ||||

| Variables | Mean group 0 | Mean group 1 | Difference(+) | F(+) | Adjust R2 |

| PolEnergy | 52.67042 | 74.13479 | -21.46437⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | 1489.89⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | 0.1371 |

| CrisisSystem | 66.68807 | 74.95365 | -8.265577⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | 713.67⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | 0.0707 |

| CSRAwards | 66.43188 | 77.49060 | -11.05872⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | 1859.14⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | 0.1656 |

| CSRCommit | 57.53902 | 75.27809 | -17.73907⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | 2379.74⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | 0.2025 |

| Panel B: MSCI EM Europe index | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference of means test (t-test) | ANOVA test | ||||

| Variables | Mean group 0 | Mean group 1 | Difference(+) | F(+) | Adjust R2 |

| PolEnergy | 32.34093 | 62.35729 | -30.01635⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | 475.22⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | 0.1147 |

| CrisisSystem | 50.8835 | 66.65661 | -15.77311⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | 238.85⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | 0.0285 |

| CSRAwards | 49.94138 | 61.39498 | -11.4536⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | 76.69⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | 0.1568 |

| CSRCommit | 51.24941 | 64.76409 | -13.51468⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | 159.20⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | 0.0887 |

Tables 7 and 8 show the results of the four applied models for the MSCI Europe index (Models a) and the MSCI EM Europe index (Models b).

Regressions in the MSCI Europe index.

| Variable | OLS RegressionModel 1a | OLS RegressionModel 2a | OLS RegressionModel 3a | FERegressionModel 4a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 15.61455⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 13.72603⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 8.806163⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 159.2251⁎⁎⁎(0.000) |

| ESGScore (1lag) | 0.1158756⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | -0.0328267⁎⁎⁎(0.001) | ||

| PWomen | 0.1806813⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 0.368749⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 0.3814648⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 0.3667906⁎⁎⁎(0.000) |

| PWomen2 | -0.0033429⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | -0.0034478⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | -0.0033369⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | |

| TobinQ | 0.0103232⁎⁎(0.0030) | 0.0103834⁎⁎(0.029) | 0.0101002⁎⁎(0.035) | -0.0086192(0.205) |

| LnAssets | 0.8382105⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 0.8353607⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 0.7642018⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | -5.195122⁎⁎⁎(0.000) |

| Indebted | -0.0011554⁎⁎(0.027) | -0.0011487⁎⁎(0.027) | -0.001435⁎⁎⁎(0.010) | 0.0002153(0.793) |

| PolEnergy | 8.815335⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 8.735851⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 8.58084⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 8.185782⁎⁎⁎(0.000) |

| LnCO2Emis | 0.7642301⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 0.7597481⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 0.642392⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 0.449099⁎⁎⁎(0.000) |

| CrisisSystem | 2.427077⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 2.2376778⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 2.262122⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 1.686418⁎⁎⁎(0.000) |

| CSRAwards | 7.482084⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 7.453579⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 7.349961⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 6.999983⁎⁎⁎(0.000) |

| CSRCommit | 10.3471⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 10.2595⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 9.520561⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 9.211814⁎⁎⁎(0.000) |

| Industry dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.4198 | 0.4218 | 0.4297 | 0.5501 |

| F-statistic | 343.97⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | 328.68⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | 287.36⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | 319.35⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) |

| Breusch-Pagan test | 1.58⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | |||

| Hausman test | 3,593.66⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | |||

| Number of observations | 8,535 | 8,535 | 7,602 | 7,602 |

| AIC | 63,931.30 | 63,901.93 | 56,847.37 | 55,293.43 |

| BIC | 64,065.29 | 64,042.97 | 56,993.03 | 55,376.67 |

***, ** and * indicate a significance of less than 1 %, less than 5% and less than 10%, respectively.

AIC and BIC: smaller is better.

Regressions in the MSCI EM Europe index.

| Variable | OLS RegressionModel 1b | OLS RegressionModel 2b | OLS RegressionModel 3b | FERegressionModel 4b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 28.40439⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 29.17561⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 25.18989⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 18.96203(0.595) |

| ESGScore (1lag) | 0.1532635⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 0.1110352⁎⁎⁎(0.001) | ||

| PWomen | 0.2155394⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 0.6158479⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 0.6655296⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 0.736466⁎⁎⁎(0.000) |

| PWomen2 | -0.0117011⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | -0.0145564⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | -0.0146648⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | |

| TobinQ | -0.1071906(0.850) | -0.0840131(0.881) | 0.2798806(0.659) | -0.0599791(0.960) |

| LnAssets | -0.1238272(0.617) | -0.1920469(0.433) | -0.2839977(0.291) | 0.1605331(0.910) |

| Indebted | 0.0006361(0.703) | 0.0004355(0.791) | -0.0005052(0.764) | -0.0001019(0.958) |

| PolEnergy | 22.28605⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 21.6457⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 20.73485⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 22.1738⁎⁎⁎(0.000) |

| LnCO2Emis | -0.0537274(0.718) | -0.0097033(0.947) | -0.1583998(0.322) | -0.1981179(0.263) |

| CrisisSystem | 9.003982⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 8.901034⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 9.030383(0.000) | 9.089376⁎⁎⁎(0.000) |

| CSRAwards | 3.786627⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 4.009257⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 3.923335⁎⁎⁎(0.001) | 3.407336⁎⁎⁎(0.006) |

| CSRCommit | 5.852971⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 4.777914⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 4.739763⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 3.570833⁎⁎⁎(0.002) |

| Industry dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.5732 | 0.5850 | 0.5981 | 0.6077 |

| F-statistic | 51.95⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | 51.51⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | 41.03⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | 62.65⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) |

| Breusch-Pagan test | 1.27*(0.0673) | |||

| Hausman test | 42.54⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | |||

| Number of observations | 646 | 646 | 512 | 512 |

| AIC | 4,864.778 | 4,847.627 | 3,825.031 | 3,712.036 |

| BIC | 4,945.253 | 4,932.573 | 3,909.798 | 3,762.896 |

***, ** and * indicate a significance of less than 1 %, less than 5% and less than 10%, respectively.

AIC and BIC: smaller is better.

Firstly, Models 1a and 1b applied OLS regression and verified a positive and significant relationship between the percentage of women on the board of directors and CSR performance in both of the samples studied. Second, Models 2a and 2b included the quadratic term of the independent variable to check if the relationship between CSR performance and the percentage of female members on the company's board was linear or non-linear. In the two samples, the coefficient of PWomen was positive and significant at the highest level (p-value lower than 0.01 in both cases), and the coefficient of PWomen2 was negative and with maximum significance (p-value is also lower than 0.01 in both cases). Therefore, the sign of the coefficients of PWomen and PWomen2 confirmed that the relationship between the independent and dependent variables was inverted U-shaped in both developed and emerging European markets.

Consequently, we included the lagged dependent variable (1 lag) as an explanatory variable in Models 3a and 3b. The results were in line with the precedent models, confirming an inverted U-shaped relationship. To conclude, we combined time-series and cross-sectional data in panel data with fixed effects in Models 4a and 4b since the Hausman test presented a p-value smaller than 0.05, so the fixed effects option was preferred to random effects.

To select the best of the four models in each study, we applied, on the one hand, the Breusch-Pagan test, which indicated that panel data models were, in both indices, better than pooled models by considering the same variables. Namely, Model 4a was better than Model 3a and, analogously, Model 4b was better than Model 3b. On the other hand, the AIC and BIC criteria determined that Model 4a > 3a > 2a > 1a, where > indicates “more preferred than”. Analogously, Model 4b > 3b > 2b > 1b. Finally, when we observed the adjusted R2, the gradation of selected models was the same. The proportion of variance explained in the study of the MSCI Europe index was 55.01% and in the study of the MSCI EM Europe index was 60.77%.

In conclusion, Model 4a was the best in the sample of the MSCI Europe index and Model 4b in the sample of the MSCI EM Europe index. Accordingly, we can affirm that the percentage of women on the board of directors influenced CSR performance positively up to a specific limit. Beyond this, influence turned negative, both in developed and emerging European markets. Therefore, our hypotheses H1 and H2 were confirmed since gender diversity on the board of directors was positively related to company CSR performance, both in the sample of the MSCI Europe index and in the MSCI EM Europe index sample.

Next, we determined the turning point in the relation between gender diversity and CSR performance. We performed a regression considering only the percentage of female directors as an explanatory variable and including the quadratic term. Results revealed that the maximum for the MSCI Europe index barely exceeded 42%. For the MSCI EM Europe index, the value was almost 20%. Figure 1 and 2 depicts the scatter graphics for the two indices.

We want to highlight the difference between the two samples for company size and CO2 emissions for the remaining control variables. Company size is negatively related to CSR performance significantly in developed countries, while its coefficient is positive and no significant in emerging markets. Thus, the largest companies have less CSR performance in developed countries, but the size is not influential in social and environmental rating in developing markets. A similar situation, but with the opposite sign, occurs with CO2 emissions. Companies in developed European countries with higher CO2 emissions also have higher ESG scores, while companies located in emerging European markets have lower ESG scores.

In the results reported, we do not include the coefficients and their significance for the industry dummies variables in OLS regressions (obviously, in fixed effects, the industry dummies variables have not to sense). In this regard, we would like to point out that there are two significant sectors. In Model 3a, financials companies presented a negative and significant relationship with ESG score, while in Model 3b, the relationship was positive. However, the healthcare sector showed a positive and significant relationship in developed and emerging markets.

Table 9 shows the results of including the interaction effects of size and CO2 emissions with gender. In developed and developing markets, fixed effects models (Models 6a and 6b) outperform OLS regression models (Models 5a and 5b). However, looking at the R2 coefficient and the AIC and BIC criteria, these models do not improve validity but remain at similar levels to those shown by Models 4a and 4b.

Moderating effects.

| Variable | MSCI Europe index | MSCI EM Europe index | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OLS RegressionModel 5a | FERegressionModel 6a | OLS RegressionModel 5b | FERegressionModel 6b | |

| Intercept | 13.3264⁎⁎⁎(0.001) | 156.2351⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 16.72922⁎⁎(0.030) | 16.21849(0.647) |

| ESGScore (1lag) | 0.1162109⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | -0.031859⁎⁎⁎(0.002) | 0.1448101⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 0.1055623⁎⁎⁎(0.001) |

| PWomen | 0.2540861⁎⁎(0.041) | 0.4307462⁎⁎⁎(0.001) | 1.82515⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 1.329165⁎⁎(0.014) |

| PWomen2 | -0.0038168⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | -0.003593⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | -0.0184862⁎⁎(0.000) | -0.018418⁎⁎⁎(0.000) |

| TobinQ | 0.0100955⁎⁎(0.035) | -0.0081729(0.229) | 0.165159(0.792) | -0.1403601(0.905) |

| LnAssets | 0.2612068(0.130) | -5.306079⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | -0.2731385(0.375) | 0.0116957(0.993) |

| PWomen x LnAssets | 0.0167749⁎⁎⁎(0.002) | 0.0059985(0.281) | -0.0042789(0.808) | 0.0110717(0.585) |

| Indebted | -0.0014618⁎⁎⁎(0.009) | 0.0002156(0.793) | -0.0004093(0.804) | -0.0001409(0.941) |

| PolEnergy | 8.381315⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 8.017078⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 21.79089⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 22.60909⁎⁎⁎(0.000) |

| LnCO2Emis | 1.174638⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 0.8761223⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 0.3693637*(0.070) | 0.2236068(0.324) |

| PWomen x LnCO2Emis | -0.0186642⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | -0.014939⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | -0.0731143⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | -0.059185⁎⁎⁎(0.003) |

| CrisisSystem | 2.336798⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 7.739875⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 9.635431⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 9.607239⁎⁎⁎(0.000) |

| CSRAwards | 7.264523⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 6.934434⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 4.334775⁎⁎⁎(0.001) | 3.802962⁎⁎⁎(0.002) |

| CSRCommit | 9.647796⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 9.310146⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 4.548951⁎⁎⁎(0.000) | 3.421014⁎⁎⁎(0.003) |

| Industry dummies | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.4319 | 0.4686 | 0.6113 | 0.6077 |

| F-statistic | 263.66⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | 302.40⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | 39.27⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | 62.65⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) |

| Hausman test | 3288,54⁎⁎⁎(0.0000) | 31.90⁎⁎⁎(0.0025) | ||

| Number of observations | 7,602 | 7,602 | 512 | 512 |

| AIC | 56,820.13 | 55,279.39 | 3,809.88 | 3,705.37 |

| BIC | 56,979.66 | 55,376.49 | 3,903.12 | 3,764.71 |

***, ** and * indicate a significance of less than 1 %, less than 5% and less than 10%, respectively.

AIC and BIC: smaller is better.

The interaction term is not significant for firm size, except in Model 5a, where a pure moderation effect does appear. However, there is a significant interaction with CO2 emissions, which can be called competitive due to its negative sign (Nitzl et al., 2016).

To better understand how this effect works, each sample was divided into two subsamples, depending on whether CO2 emissions were lower or higher than the median of their distribution. Then the function relating the percentage of women on the board of directors to the ESG score was adjusted in both cases, showing striking differences as shown in Figs. 3 and 4.

For developed countries, maximum gender diversity benefits CSR when CO2 emissions are lower, but most women are more beneficial when emissions are higher. Similarly, when companies produce higher CO2 emissions in developing countries, greater diversity is required to achieve better CSR performance.

5Discussion and conclusionsThe fifth sustainable development goal in the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda is gender equality, including equal presence at the management positions. Likewise, countries have required gender quotas on company boards, mainly in public companies and listed companies in the exchange markets. European countries are at the forefront of establishing legal quotas (Valls Martínez & Cruz Rambaud, 2019; Valls Martínez et al., 2019). However, this fact is not without its criticism. On the one hand, many people think that women should be hired by their education and experience, not because of their sex. On the other hand, private companies are not instruments of social change, especially in a free market, but entities require benefits to survive. They must have the freedom to hire directors according to their criteria and needs. Even if women are hired based on the legal quota, they are likely to be discriminated against by their male counterparts and their opinions are not considered (Gennari, 2018). Namely, companies would implement gender diversity only if they have additional economic benefits (Bernardi & Threadgill, 2010).

2030 Agenda has strengthened the importance of CSR performance, and companies are, at this moment, more involved in the implementation of activities aimed at social and environmental issues (Williams et al., 2019). Companies have to be more accountable than ever to mitigate the adverse effects caused by economic development. From a social role perspective, women are more sensitive to the environment and empathetic to social problems. Therefore, a higher percentage of women on the board of directors will increase the CSR performance of a company (Boulouta, 2013). Furthermore, from a legitimacy theory, gender equality in management positions will improve the company's image and increase its moral legitimacy in society (Zhang et al., 2013). Currently, investors require socially responsible investment. They search for companies with gender diversity, and the bigger demand in the market will imply a higher price (Gallego-Álvarez et al., 2010; Reguera-Alvarado et al., 2017). Diversity is a signal to markets that gives the company a greater degree of legitimacy and enhances its reputation. Thus, from a theoretical point of view, there are solid reasons to support gender diversity on the board of directors, and empirical studies are also necessary to build compelling arguments on which to base political theories.

The purpose of this article is to examine the impact of gender diversity on board of directors on CSR performance, both in developed and developing European markets. By comparing both types of countries in the same European context, using similar methodology, variables and analysis period (from 2010 to 2019), the results allow for consistent comparison, and it is possible to analyse whether the behaviour is similar or, conversely, whether there is any noticeable difference. Our results, in line with previous research, show that women in the boardroom increase CSR performance (Bear et al., 2010; Ben-Amar et al., 2017; Bernardi & Threadgill, 2010; Cuadrado Ballesteros et al., 2015; Dienes & Velte, 2016; Francoeur et al., 2019; Grigoris Giannarakis, 2014; Hossain et al., 2017; Khan et al., 2019; Kyaw et al., 2017; Manita et al., 2018; Sundarasen et al., 2016; Valls Martínez et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2013). However, we find a quadratic relationship between the percentage of women directors and the extent of the company's CSR, a U-shaped inverted curve. Therefore, the ideal frame is to increase gender diversity since a low percentage of women on the board of directors is not appropriate to the company's performance. Likewise, if the percentage of men is low, the company's performance will be damaged, which has been hardly acknowledged so far (Birindelli et al., 2019; Pucheta-Martínez et al., 2019; Valls Martínez et al., 2020).

However, when distinguishing between companies with higher and lower CO2 emission levels, it is concluded that gender diversity indeed reinforces CSR performance when companies are less polluting. However, in companies with higher emissions, the majority presence of women contributes positively to implementing sustainability measures, especially in developed countries. In emerging countries, there is also an increase in the proportion of women leading to maximum CSR. Indeed, from an empirical point of view, the theories mentioned above showing the greater corporate, social and environmental sensitivity of women are confirmed.

In our empirical dataset, the average ESG score is 23.65% higher in developed countries than in emerging markets (72.92 and 58.97, respectively), indicating greater compliance of environmental, social and governance measures in companies located in developed countries.

Analogously, the average percentage of women is 195% higher in developed countries than in emerging markets (28.88 and 9.79, respectively). These patterns are in line with the general gender gap in both clusters of countries, such as we exposed in Table 2, and with the empirical turning point of women shows in Figs. 1 and 2, which is noticeably lower in emerging markets. We could infer that in developed markets the female education is higher. However, the female/male ratio in tertiary education is greater than 1 in all countries, both developed and developing, and it presents similar values (World Economic Forum, 2019). Therefore, we can affirm that the level of education is higher in women than in men in all cases.

Nevertheless, women hold management positions at a much lower rate than men, especially in emerging markets. Why are men preferred, even though diversity is beneficial to the company? Why are women's skills undervalued? (Mateos del Cabo et al., 2010)

We consider that the low percentage of women on the company board can be resolved in the medium and long-term with measures such as the following. First, making companies aware of the economic benefits they would gain from gender diversity. Empirical studies, as the present, contribute to the knowledge and diffusion of this social need. Second, proactive policies to balance work and family life are necessary. In this sense, it is appealing that the mean age of women at the birth of the first child is below 30 years old in emerging markets and about this age in developed countries (World Economic Forum, 2019). Third, gender quota policies in the board of directors are effective since European countries with these policies have increased the female presence significantly in management positions (Valls Martínez & Cruz Rambaud, 2019; Valls Martínez et al., 2019).

We want to mention that companies located in developed countries with higher CO2 emissions carry out activities to control the harmful environmental effects. In this way, they improve their ESG scores. Conversely, this is not the case in emerging markets, where mitigating measures for their polluting effects should be implemented. Moreover, it is remarkable that the healthcare sector is positively related to the ESG scores in both samples, the most sensitive sector in social and environmental issues.

To conclude, we can point out two reasons to enact legal measures to increase gender diversity on the board of directors. The first one, social justice. In effect, equal opportunity is a fundamental right, and women must hold management positions in the same proportion as men. Besides, companies with more female directors use to hire more women in the workforce (Bernardi & Threadgill, 2010). The second one, business enhancement. A higher female presence on board improves the company CSR performance, as was stated above. Gender diversity legitimizes companies and increases their reputation, which leads investors to select these shares in their portfolios, increasing the stock prices (Gallego-Álvarez et al., 2010; Reguera-Alvarado et al., 2017). In effect, the McKinsey Global Institute established that global incomes would increase more than 25% in the gender parity scenario (Gennari, 2018).

Finally, we believe that the positive and robust relationship found in most studies between women and CSR performance is reinforced by the fact that women are relegated to soft management positions, as CSR areas, human resources, auditing committees or marketing, but is not usual find women as CEO or chief in the financial department. Thus, even in direction, there is discrimination against women (Furlotti et al., 2019; R. J. Williams, 2003). Suppose the most polluting companies have to make a significant effort to comply with legal regulations and legitimize themselves in the eyes of markets and society. In that case, it is logical to think that they are the ones with the most developed CSR committees. If women are assigned to this type of committee, among others, in a particular way, perhaps part of the positive relations between women on boards of directors and CSR that empirical research is finding is nothing more than a consequence of the discrimination that women still suffer today. We believe that, in the future, research along these lines should be carried out.

The findings of this empirical study have useful implications for investors and practitioners. For investors since a higher female presence on the board of directors enhances the company's performance. For policymakers since gender diversity in management positions lead to a more sustainable world. Thus, we can conclude that gender equality law is a valuable instrument to reduce the gender gap and foster the enhancement of CSR scores in companies. Therefore, legal gender quotas contribute to building a more sustainable world in the sense of the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda. Nevertheless, we have not forgotten that such legal quotas must be accompanied by other rules that help to balance work and family life.

Finally, we acknowledge the limitations of our study. First, the sample of the MSCI indices could be extended to small and medium companies. Second, it would be interesting to study other markets, in addition to the European market.

Conflict of InterestThere is no conflict of interest.

María del Carmen Valls Martínez gratefully acknowledges Grupo Unicaja and Unicorp Patrimonio corporations for their collaboration.