The objective of this study is to analyse the effect of four export barrier groups – human capital, cultural, administrative, and financial – on the product export barrier. The study participants constitute a statistically significant sample of 318 exporting companies in Brazil. The research model is tested using structural equation modelling, specifically the partial least squares (PLS-SEM) technique, and SmartPLS version 3.2.9. The results confirm that there is a significant effect of three export barriers – human capital, cultural, and financial – on the product export barrier. The effect of the administrative barrier on the product barrier is not verified. Besides, the effects of the human capital barrier on the cultural barrier and the administrative barrier on the financial barrier are verified. The mutual interaction between export barriers makes it advisable to manage each type of barrier.

In the global business environment, companies are increasingly seeking to internationalize their markets (Bagheri et al., 2019; Jafari-Sadeghi et al., 2020). Exporting is an essential strategy for internationalization (Cano-Rubio et al., 2017; Jean & Kim, 2020). Firms benefit from exporting due to economies of scale, the opportunity to increase their performance while reducing their risk, and improvements in production efficiency as well as becoming more attractive to shareholders and employees, among other reasons (Sinkovics et al., 2018). However, achieving these benefits has often proven to be problematic due to a series of barriers that impede the export process (Leonidou, 1995a). Therefore, export barriers have been a key research topic in the international business discipline in recent decades (Leonidou et al., 2010).

In the export process, barriers pose a significant challenge for exporting companies (Alon et al., 2019; Kahiya & Dean, 2016), making it difficult for them to distribute products and services to foreign markets (Nam et al., 2018; Tan et al., 2018). The barriers have been distinguished into different typologies (Ramaswami & Yang, 1990), for example internal and external barriers, which affect different countries. In particular, it has been pointed out that internal barriers could affect emerging economies with human capital problems more deeply (Uner et al., 2013).

An added problem of export barriers is that they interact with one another (Mendy & Rahman, 2019). In other words, there are negative interactions between export barriers. For instance, the problem of human capital – insufficient employee skills and knowledge of the export process – affects the marketing and sale of products abroad. However, it can also influence the knowledge of the culture of the country to which the exports are directed, increasing the difficulty of the export process. This is the research gap that previous studies have ignored and the present study aims to fill.

This study is structured around one research question: are there negative interactions between export barriers? Thus, this work has one objective: to analyse the impact of four export barriers – human capital, cultural, administrative, and financial – on the product export barrier. The product export barrier is related to the problems of production and marketing of products for exporting (Tesfom & Lutz, 2006). The issue here is to fit the product to the level of demand and the enforceability required by importers. This is a difficulty that Brazilian exporters face and could be considered to be a barrier in the final stages of the export process (Li et al., 2010).

Therefore, this work makes important contributions to both the management of exporting companies and the literature on internationalization. With reference to management, analysing the negative interactions between the export barriers and the intervention of the size of the exporting firm in the relationships between barriers can assist exporting companies in implementing strategies that help to mitigate their effects, considering that Latin American companies face more significant difficulties in internationalization than their European counterparts (Vendrell-Herrero et al., 2017).

With respect to the literature, this work contributes to the knowledge of the internationalization phenomenon in Latin America, especially in Brazil (Cahen & Mendes Borini, 2020), where less research has been conducted on internationalization processes than in the emerging Asian Pacific countries (Da Rocha et al., 2012). This research helps to provide knowledge about the behaviour of export barriers in emerging countries, where, as Kahiya (2018) pointed out, there is a significant gap in research on export barriers. More specifically, in Brazil, no research has addressed the problem of export barriers throughout the country. Furthermore, this work proposes a classification of export barriers and strategies to reduce their impact.

This work is organized in four sections. In the first section, an examination of the export barriers is presented and the possible relationships between them are explored. In the second section, the research methodology is described; the empirical work is carried out with a statistically significant sample of 318 exporting companies in Brazil, the largest country in South America (Azzi da Silva & da Rocha, 2001). In the third section, the analysis of the results is presented. The fourth section contains the discussion and proposes strategies to reduce the impact of export barriers.

2Theoretical framework2.1Concept and types of export barriersThe term “export barriers” refers to all the limitations that hinder the ability of companies to initiate, develop, or maintain commercial operations in foreign markets (Leonidou, 2000). These obstacles to accessing these types of markets can limit companies’ potential to exploit opportunities in foreign markets (Santos-Álvarez & García-Merino, 2016), weaken their financial performance, delay their internationalization progress, and even cause the complete abandonment of their foreign trade operations (Gou et al., 2016).

The obstacles, difficulties, or barriers to exports are numerous and are perceived in different ways and with different degrees of intensity by companies (Leonidou, 2004). The literature has proposed different types of barriers to exports. Morgan and Katsikeas (1997) identified three groups of export barriers: (1) strategic barriers, (2) operational barriers, and (3) informational barriers. Cavusgil (1984), Leonidou (1995a, 2000), and Tesfom et al. (2006) differentiated between internal barriers and external barriers. Arteaga-Ortiz and Fernández-Ortiz (2010) and Suárez-Ortega (2003) grouped export barriers into four generic categories: (1) knowledge, (2) resources, (3) procedures, and (4) exogenous. Altintas et al. (2007) adopted a wide classification and recognized 20 types of export barriers. Mendy et al. (2020) described three categories of export barriers: social barriers, political barriers, and economic barriers.

Based on a review of the literature, especially the classic authors on internationalization by exporting (see Table 1), we propose a typology that identifies five generic categories of export barriers: (1) human capital, (2) culture, (3) product, (4) administrative (bureaucratic and tariff), and (5) financial. This classification of export barriers has been constructed according to the similarities between export barriers (Mataveli, 2014), aiming to simplify the number of barrier groups to facilitate further theoretical studies or empirical analysis. Besides, this classification follows Kahiya's (2013) suggestion that export barriers cover a wide range of impediments that are related to the attitudes and behaviour of the agents who intervene in the exports and to the structures of the organizations and the institutional relationships that, individually or jointly, can discourage firms from engaging in international expansion.

Typology of export barriers.

| Type of Export Barriers | Authors |

|---|---|

| Human Capital Barriers.■ Lack of qualification of the management teams to export.■ Lack of specialized personnel in the company to export.■ Lack of knowledge of potential markets for the product.■ Lack of distribution channels.■ Unawareness of the steps to export. | Barker and Kaynak (1992)Hutchinson et al. (2006)Julian and Ahmed (2005)Kedia and Chokar (1986)Leonidou (1995b, 2004)Yang et al. (1992) |

| Cultural Barriers■ Customs differences of exporting countries.■ Cultural differences of export countries.■ Linguistic differences of export countries. | Brouthers and Brouthers (2001)Evans and Mavondo, (2002)Ghemawat (2001, 2007)Sousa and Bradley (2005) |

| Product Barriers■ Lack of production capacity.■ Problems of technological capabilities of the company with its competitors.■ Problems adapting your product to external markets.■ Obtaining distributor of your product. | Cavusgil and Zou (1994)Hutchinson et al. (2007)Katsikeas and Morgan (1994)Lages and Montgomery (2004)Leonidou (1995a, 2004) |

| Financial Barriers■ Financial costs in foreign trade and Exchange operations.■ Lack of obtaining bank guarantees.■ Problems of limited of credit■ Problems in obtaining credit lines.■ Shortage of financial resources.■ Credit insurance problems. | Julian and Ahmed (2005)Katsikeas and Morgan (1994)Leonidou (2004)Silva and Rocha (2001) |

| Administrative Barriers (customs and non-customs)■ Customs barriers.■ Documentation and bureaucracy to the export activity.■ Obtaining documents and licenses.■ Customs taxes.■ Sanitary, phytosanitary and quantity barriers. | Barker and Kaynak (1992)Cavusgil (1984)Leonidou (1995b)Leonidou (2004)Rabino (1980)Ramaswami and Yang (1990)Silva and da Rocha (2001) |

Notes: own elaboration

In this section, the concept of product export barriers is explained and hypotheses about the relationships between export barriers are proposed.

Product barriers can be identified as the difficulties faced by firms in developing their products, making them suitable for satisfying the needs of international markets, and marketing them abroad. There are some adaptation prerequisites to be met, for instance the quality characteristics required in the country to which the product is being sold or commercialization and adaptation to aspects of the foreign market related to the product to be exported, such as packaging or labelling (Leonidou, 2000, 2004; Silva & Rocha, 2001). It has been proven that the ease of manufacturing for exports encourages the internationalization process (Johnston et al., 2019).

In addition, the commercial promotion abroad and the after-sales service and/or technical assistance constitute important difficulties that companies face in their foreign trade activity. In this sense, some studies (Silva & Rocha, 2001; Tseng & Balabanis, 2011) have pointed out the specific difficulties that Brazilian companies face in adapting their products to the foreign market.

Human capital plays a vital role in companies, especially in the case of exports due to the particular characteristics of the export process because the foreign market is significantly different from the national market (Brenes et al., 2014). Managers’ lack of preparation for foreign trade is a substantial barrier to exports (Tesfom et al., 2006). Considering this point of view, if a company does not have managers who engage in international activities or specialized personnel who have been trained in them, human capital will act as an essential barrier to exports (Barker & Kaynak, 1992). Mury (2016) pointed out that one reason for Brazilian companies not putting greater emphasis on exports is their managers’ lack of motivation concerning internalization.

Meanwhile, the problem of human capital could lead to a lack of knowledge about the export process and its advantages. Several authors (Fu et al., 2018; Vissak et al., 2020) have already stated that the barriers related to knowledge problems are the most important in international trade, considering that foreign trade activity is largely based on knowledge about the export process; in fact, an important rationale for internationalization is to access advanced knowledge. Disregarding the needs and the exigencies of different markets, assistance programmes for exports and, above all, the export potential are barriers that prevent companies from carrying out efficient export processes (Ramaswami & Yang, 1990). For all these reasons, we suggest the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Human capital barriers are positively associated with product barriers.

Other types of barriers to exports include cultural barriers or cultural distance (Freire & Rocha, 2003); these involve the culture of countries (Li et al., 2019) and are a product of differences in cultural values between different regions or countries (Beugelsdijk & Mudambi, 2013). In this sense, the cultural values, ways of life, or aesthetics of different cultures should be considered while planning an internationalization process. These cultural barriers have a close relationship to the so-called “psychic distance”, which sometimes acts as an export barrier (Assadinia et al., 2019). The psychic distance refers to the differences in people's language and values between countries (Bello & Gilliland, 1997).

An additional consideration in this regard is the theory of culture (Hofstede, 1980), which implies that internationalization requires a company to understand the different cultures at play in these markets and consider the effect that they might have on the company's product or service and the typical market. The more significant the cultural difference, the greater the uncertainty for a manager and the more significant the potential competitive disadvantage for the company relative to companies that already serve those international markets. The extent to which national, regional, or local cultures have an impact on international entrepreneurship is not clear (Perks & Hughes, 2008). Studies and theories from cognitive psychology and sociology suggest that intercultural factors can influence entrepreneurs’ decision making and therefore justify their consideration (Zahra et al., 2005).

In general, cultural barriers restrain the performance of international trade operations (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977), although cultural distance does not always affect the different stages of internationalization equally. Thus, the study by Beugelsdijk et al. (2018) confirmed that cultural distance is more significant at the stage of export integration or transfer than, for example, the choice of location. Thus, the lack of consideration of specific cultural issues can lead to the failure of commercial enterprises that cross national borders (Voldnes & Gronhaug, 2015). For all the above reasons, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Cultural barriers are positively associated with product barriers.

It could be appropriate to think that cultural barriers are intensified by a lack of knowledge about the culture of the country to which the goods are being exported. In this case, ignorance of different cultures could hinder the development of international trade – for instance through mistakes in the language, even if the same language is spoken, as there might be idiomatic differences. Then, companies that seek to reduce the impact of cultural barriers to exports must invest in the development of human capital (Wagner et al., 2019). Therefore, a lack of knowledge about cultural behaviours can become a significant barrier to exports (Swift, 1999). In this sense, to succeed in today's global business market, it is vital to understand and manage cultural differences (Voldnes & Gronhaug, 2015). Thus, we suggest the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: Human capital barriers are positively associated with cultural barriers.

Another essential type of generic barrier to exports is administrative barriers, which include bureaucratic and customs barriers. Bureaucratic barriers profoundly affect export decisions in companies and can frequently inhibit their export activities and sometimes completely discourage them. Respected authors have indicated that bureaucracy is one of the most significant barriers to exports (Ramaswami & Yang, 1990). The excess paperwork and documentation required for operations, in addition to the complicated and lengthy customs procedure, can become a strong impediment to exports (Okpara & Kabongo, 2010), added to the inadequate management of banks and customs at borders 24 hours a day, which causes delays in the release of the merchandise (Silva & Rocha, 2001). In addition to customs procedures are other types of barriers, such as sanitary and phytosanitary regulations, which significantly reduce the export opportunities of developing countries and their compliance with specific quality standards (Ehrich & Mangelsdorf, 2018). Tariff barriers, which are understood as the official tariffs that are set and charged to importers and exporters in a country's customs for the entry and exit of merchandise, become a significant barrier to exports (Magee et al., 2019). One purpose of this type of legal barrier is to inhibit the entry of specific merchandise and services into a country through the establishment of import duties. In addition, it should be considered that inappropriate legislation regarding exports, for example numerous administrative requirements, could make it difficult to export products. Nevertheless, it has been pointed out that variables such as bureaucracy affect the provision of products to export. Some products, such as perishable, cyclical, and high-benefit products, seem to be more sensitive to this type of barrier (Zaki, 2015). Considering all of the above, we present the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4: Administrative barriers are positively associated with product barriers.

Following the typology of barriers to exports, the last group of barriers proposed is financial barriers. Financial barriers are fundamentally barriers to credit access as well as other problems related to credit, such as a shortage of financial resources in particular types of companies, or more specific aspects, such as the high financial costs of foreign trade. A shortage of credit for foreign trade is a significant export barrier (Ramaswami & Yang, 1990). Exporting companies need credit either for the pre-shipment (production) or for the post-shipment period because credit allows the financing of sales and the realization of market analysis (Leonidou, 2004). Therefore, the literature has shown the significant negative impact that a lack of credit exerts on exporting companies (Berman & Hericourt, 2010). In contrast, a country's financial development significantly facilitates exports (Linh et al., 2019).

On the other hand, Ramaswami and Yang (1990) pointed out, as barriers related to credit, the lack of interest on the part of banks in financing small businesses and the lack of financing for market research. Leonidou (2000, 2004) stated that emphasis is placed on this problem of high costs as well as other problems, such as the scarcity of transport subsidies or the delay in the collection of external payments (Silva & Rocha, 2001). Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5: Financial barriers are positively associated with product barriers.

In general, the relationship between the institutional environment of the country of origin and the export behaviour of companies has been highlighted. In this sense, works such as that by Tsukanova (2019) have empirically proven how fiscal and financial barriers define small and medium-sized businesses’ propensity to export. As stated previously in relation to problems with access to export financing, it could be correct to think that administrative bureaucracy is connected to this export problem because it means a greater need for credit to finance taxes or to deal with the requirement for particular adaptations of products to foreign trade (Thompson, 2018). Therefore, we present the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 6: Administrative barriers are positively associated with financial barriers.

In this work, one control variable is considered. Company size is a variable that has an impact on internationalization and the export process (Cos et al., 2019; Gaur et al., 2019; Suárez-Porto & Guisado-González, 2014). It has been pointed out that, generally, large companies face fewer difficulties than small enterprises in export business (Silva et al., 2016). Works such as the study by Adu-Gyamfi and Korneliussen (2013) have found that the size of a firm is related to internal barriers, for instance a lack of competent personnel to administer exporting activities. Generally, access to credit is influenced by the firm size (Oktaviani et al., 2019); in the same way, the company size affects bureaucratic problems in international trade (Verwaal & Donkers, 2003).

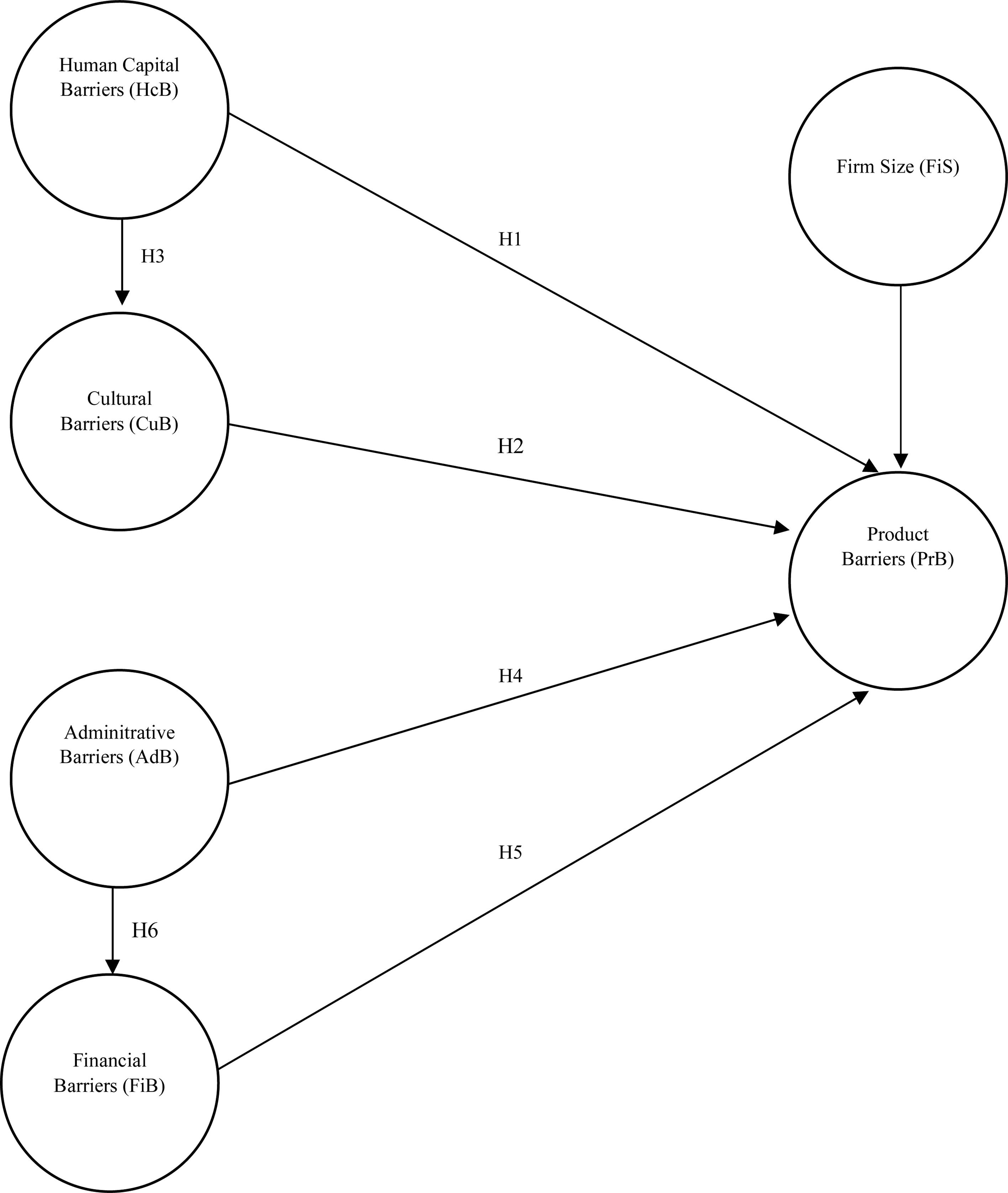

Given all of the above, we propose a joint analysis model (see Figure 1).

3Methodology3.1Sample and data collectionTo obtain the sample, we started with the database contained in the Catalog of Brazilian Exporters (CEB) (IEB, 2014), which provides information on exports extracted from the official records of the Secretariat of Foreign Trade (SECEX), the agency of the Ministry of Development, Industry and Foreign Trade (MDIC). The population consisted of 21,950 exporting companies from all sectors of the economy. Invitations were sent to the total population, and 318 valid questionnaires were collected. The sampling error was ± 4.6%, and the confidence level was 95%.

Table 2 shows the characteristics of the sample in relation to the variables that are controlled in this study, the size of the companies, and their exporting experience as indicated by the number of years for which the company has been operating with exports.

Sample characteristics of companies, and comparison between the composition of the sample and the exporting companies of Brazil.

Notes: Sources: FIESP (2012) and MDIC (2019)

Regarding the size of the companies, there is a similarity between the sample and the population of companies in Brazil. In the sample, 30.8% of companies are medium-sized exporting companies, 24.9% are small firms, 22.6% are microenterprises, and 21.7% are large companies. To identify the size of a company, the criteria of Mercosur, which considers the number of employees and the export value as variables, were adopted. Concerning the sample's economic activity sector, 23.9% of companies are agricultural exporting companies, 59.7% are industrial companies, and 16.4% are service companies.

The data were collected through a questionnaire that was carried out “ad hoc” and gathered information about Brazilian companies’ process of internalization. The questionnaire was designed on an 11-point Likert scale, where zero corresponds to total disagreement and 10 to total agreement. The questionnaire was sent to individuals who were responsible for the export area of companies, this being considered to be the most direct way to obtain the data necessary for this study.

3.2MeasuresIn relation to the nature of the constructs, the study differentiates between behavioural constructs and design constructs (“artefacts”) (Henseler, 2015). In this research, the type of construct – export barriers – resembles “artefacts”, which can be conceived as a product of a thought that, following a constructivist epistemology, is theoretically justified (Felipe et al., 2020).

This study considers 23 types of export barriers divided into five groups – human capital, cultural, product, financial, and administrative. The 23 export barriers and the five groups of barriers result from an in-depth analysis of the literature (see Table 1). The human capital group consists of five barriers, which refer mainly to the knowledge and skills problems of managers and employees regarding exports. The culture group contains three barriers, which concern the cultural and linguistic differences between countries. The product group consists of four barriers, which correspond to problems in the adaptation and distribution of products for exporting. The finance group encompasses six barriers concerning credit problems related to financial export and exchange costs. The administrative group comprises five barriers linked to customs documentation and sanitary requirements.

3.3Data analysisThe research model is tested with structural equation modelling through the partial least squares (PLS-SEM) technique and the SMARTPLS software, version 3.2.9 (Ringle et al., 2015). As Henseler (2016) pointed out, partial least squares modelling (PLS) is a multivariate statistical technique that is frequently used in various disciplines of business research (Henseler et al., 2009). PLS-SEM is chosen because it is considered to be a suitable technique for analysing the artefact type constructs (Henseler, 2017). In our case, the constructs are modelled as composite Mode A. Besides, PLS-SEM is considered to be appropriate for analysing models with direct relationships between variables (Roldán & Sánchez-Franco, 2012).

4Results4.1Measurement modelThe analysis of the measurement model involves four stages: (1) the individual reliability of the indicators, (2) the reliability of the constructs, (3) convergent validity, and (4) discriminant validity. First, the reliability of the indexes must be analysed through their loads. In this case, the factorial loads prove to be higher than 0.7 for most of the items, and they are never lower than 0.4, the limit that was indicated by Hair et al. (2011). Therefore, a group of scales with 23 items remains in the proposed model (see Table 3).

Measurement model – reliability, and convergent validity.

Notes: HcB: Human capital Barriers; CuB: Culture Barriers; PrB: Product Barriers; FiB: Financial Barriers; AdB: Administrative Barriers. CR: Composite Reliability; AVE: Analysis of the extracted variance

Second, the reliability of the construct is examined with Cronbach's alpha and the composite reliability index. Third, the existence of convergent validity is confirmed by means of the average variance extracted. The results show a composite reliability value that exceeds the critical value of 0.8 for all the variables (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994), and the average variance value extracted is above 0.5 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981), so the reliability and convergent validity are verified (see Table 3).

Finally, the analysis of the measurement model consists of the verification of the existence of discriminant validity. To confirm the discriminant validity of the study's constructs, first, we use the criterion of Fornell and Larcker (1981), which requires the square root of the AVE to be higher than the correlation between constructs. Second, we use the heterotrait–monotrait correlation ratio (HTMT – 90) approach (Henseler et al., 2015), and the inference tests show that none of the confidence intervals contain the value one; this result suggests that all the variables are empirically different. For both approaches, our scales meet the requirements, thereby indicating their discriminant validity (Table 4).

Discriminant validity.

| Construct | AdB | CuB | FiB | HcB | PrB | FiS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fornell and Larcker's (1981) Criteria | ||||||

| Administrative Barriers | 0.807 | |||||

| Cultural Barriers | 0.609 | 0.869 | ||||

| Financial Barriers | 0.526 | 0.608 | 0.828 | |||

| Human Capital Barriers | 0.487 | 0.660 | 0.510 | 0.832 | ||

| Product Barriers | 0.507 | 0.740 | 0.616 | 0.839 | 0.790 | |

| Firm Size | 0.086 | 0.053 | 0.017 | -0.107 | -0.150 | 1.000 |

| Heterotrait-monotrait ratio HTMT | ||||||

| Administrative Barriers | ||||||

| Cultural Barriers | 0.713 | |||||

| Financial Barriers | 0.568 | 0.689 | ||||

| Human Capital Barriers | 0.555 | 0.756 | 0.566 | |||

| Product Barriers | 0.594 | 0.888 | 0.717 | 0.902 | ||

| Firm Size | 0.090 | 0.105 | 0.079 | 0.113 | 0.167 |

Notes: BBu: Bureaucracy Barriers; CaB: Capital Barriers; CuB: Cultural Barriers; ExE: Experience; FiB: Financial Barriers; PrB: Product Barriers; FiS: Firm Size.

To determine the statistical significance of the “path” coefficients, the bootstrapping technique is utilized with 5,000 subsamples (Hair et al., 2011). Besides, the effect size (f²) is reported for the relationships in our structural model following the recommendation of Hair et al. (2014).

As shown in Table 5 and Figure 2, our results contrast with H1, indicating the impact of the human capital barrier on the product barrier (0.566***). H2, showing the impact of the culture barrier on the product barrier (0.282***), is contrasted. Furthermore, H3, indicating the impact of the human capital barrier on the culture barrier (0.660***), is contrasted. On the contrary, H4 (0.020) is not contrasted, and administrative barriers do not affect product barriers. Contrasting with H5, the impact of the financial barrier on the product barrier is shown (0.168***). In addition, contrasting with H6, indicating the impact of the administrative barrier on the financial barrier (0.526***). Furthermore, the firm size result is statistically significant (-0.105***).

Result of the structural model.

Notes: HcB: Human capital Barriers; PrB: Product Barriers; CuB: Cultural Barriers; AdB: Administrative Barriers; FiB. Financial Barriers; FiS: Firm Size; ns = not significant, (based on t(4999), one-tailed test) t(0.05;4999) = 1.645; t(0.01, 4999) = 2.327; t(0.001, 4999) = 3.092; (based on t(4999), two-tailed test); t(0.05, 4999) = 1.960, t(0.01, 4999) = 2.577; t(0.001, 4999) = 3.292; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Following Cohen (1988), regarding the size of the substantive effect, H1, H3, and H6 show significant effects, while H2, H4, and H5, the relationships related to the control variables, are not significant. Especially significant is the relationship between the knowledge barrier and the product barrier (f² = 0.803) and that between the knowledge barrier and the cultural barrier (f² = 0.771).

The use of the importance-performance map analysis (IPMA) has been recommended to identify the constructs in the structural model that are relatively important and/or have a relatively higher yield (Hair et al., 2014). This type of analysis is valuable because it broadens the findings of the PLS-SEM analysis, which offers direct, indirect, and total relationships, and enables the inclusion of another dimension that shows the real performance of each construct (Alkali & Mansor, 2017).

The results in Table 6 show the importance–performance map of the indicators, indicating that administrative barriers have the highest performance (73.166) and a relatively low total effect (0.069). This barrier is followed by the financial barrier, with 65.067for performance and 0.282 for importance; the human capital barrier, with 56.736 for performance and 0.752 for importance; the cultural barrier, with 53.745 for performance and 0.282 for importance; and, finally, export experience, with 50.524 for performance and – 0.105 for importance.

5DiscussionThe objective of this work was to verify the effect of four export barriers – human capital, cultural, administrative, and financial – on product barriers. Except for the hypothesis concerning the relationship between administrative and product barriers, the rest of the hypotheses were positively contrasted. In addition, the other relationships between the proposed barriers were determined to be significant. These results enable us to answer the research question. It is apparent that export barriers have mutual influences. In this sense, negative interactions are generated between export barriers. Although there is little literature in this regard, these results indicate that a barrier not only has a prompt impact on an export problem but also generates problems in the rest of the export barriers and, with them, in an entrepreneurial company's propensity to export. In this sense, export barriers behave in the opposite direction to export facilitators, for instance international cooperation or the creation of joint research projects between countries (Sansavini, 2006).

Then, we focused on the more concrete relationships between export barriers’ results. The results of the analysis of the proposed model showed that the human capital barrier had the most significant impact on the model as a whole, which demonstrates the lack of knowledge about the process and the benefits of exports. The reasons for the magnitude of this barrier were highlighted in the studies that were conducted. It has a very high, statistically significant effect on both the product barrier and the culture barrier (see Figure 2). Likewise, the size effect on the product and culture barriers is very strong (see Table 5), and, lastly, both the importance and the performance are high (see Table 6). Therefore, companies must make special consideration of these barriers. Authors such as Leonidou (2000) have pointed out that this type of barrier has the most significant influence on the export process, and other works have indicated the importance of human capital in the export process. Companies that seek to reduce the impact of export barriers should invest in the development of their human capital. In this sense, training is an instrument that improves the knowledge of the export process (López-Rodríguez et al., 2018). It facilitates the work of entrepreneurship that is proposed in the export markets (Julian & Ahmed, 2012). It has also been proven that cultural differences are a vital export barrier. To minimize this type of barrier, it is necessary to acquire in-depth knowledge of other countries’ business cultures in relation to exports and the characteristics of their languages and habits (Olabode et al., 2018). Moreover, both public and private economic institutions can produce follow-ups to reduce this barrier as they have a more significant infrastructure and knowledge of local export realities. For their part, Wu et al. (2007) proposed three governance mechanisms for manufacturers to overcome cultural barriers: trust, knowledge sharing, and a relationship based on contracts. Of these three mechanisms, trust is the most effective way to reduce the opportunism of the distributor.

As the literature has pointed out (Evans & Mavondo, 2002), the cultural barrier has a significant impact on the product barrier. Besides, the effect size and the performance and importance are large. Therefore, companies should try to reduce this barrier fundamentally by generating knowledge among their managers and employees, as has been demonstrated in relation to the impact of the knowledge barrier on the culture barrier.

Contrary to what had been proposed and the literature has pointed out (Ramaswami & Yang, 1990; Robyn & Duhamel, 2008), the administrative barrier does not have a significant effect on the product barrier. However, it does have a significant effect on the financial barrier, which indicates that administrative barriers, for example customs taxes, generate financial problems. Furthermore, this barrier has high performance but low importance, meaning that companies must also pay attention to it because of the high level of performance that it allows (Phadermrod et al., 2019). In Brazil, the vast majority of companies, mainly SMEs, need help with intellectual capital to enter and remain in a foreign market as an exporter. Accordingly, they exploit the knowledge that banks, mainly official banks, give them. To a lesser extent, although statistically significant, financial barriers affect the product barrier. The product must be manufactured and marketed abroad. All these actions, in most cases, must be financed. Any financing difficulty is a problem for the production and sale of products abroad.

This work also considered the size of the company as a variable control (Cos et al., 2019). This variable was negatively significant, indicating that the larger the company, the smaller the effect of the barriers to exporting. In other words, export barriers affect small companies more than large companies. This result is consistent with the literature that has stated that large companies with a more significant number of employees have higher human capital, which minimizes knowledge problems (Ying et al., 2016). In this sense, large companies have traditionally been more internationalized since it is more expensive for small and medium-sized companies to reach international markets (Alon et al., 2019).

5.1Practical implicationsAlthough there is no consensus on the perception of export barriers due to the different methodologies used for their analysis (Da Rocha et al., 2008), there is more significant agreement on their negative impact on the export process (Uner et al., 2013). Therefore, knowing the perception of the barriers among exporting companies’ managers is especially important in the decision-making process as it can condition companies’ exporting behaviour. Our research underlines that managers see human capital as the set of knowledge, skills, talent, and experience used to add value to the company (Fletcher, 2004), and, as a crucial obstacle in the export process, overcoming this barrier implies increasing not only the direct managers’ knowledge but also their skills and initiative regarding the exploration of international markets, as highlighted by influential authors (Azzi da Silva & da Rocha, 2001). Even considering the size and potential of the Brazilian domestic market and the federal government's sometimes inadequate support for exporting (Da Rocha et al., 2009), public policy support remains essential. In this sense, it would be appropriate for managers to know the advantages that internationalization offers for the growth and development of the company, which could be an incentive to enter international markets. It is also necessary to manage the psychic distance as a cultural barrier that affects the ability to communicate because, as a consequence of this barrier, market agents could receive inaccurate information that hinders international transactions (Sachdev & Bello, 2014). Finally, it should be noted that the export process requires significant financing. Therefore, the search for adequate funding and the support of Brazilian banks’ expertise in internationalization will help companies to succeed in the export process.

In summary, managers must have a complete and conscious view of the export barriers, adequately address all of them instead of concentrating on improving their performance in relation to just one, and take the initiative to export goods.

5.2Limitations and suggestionsThe first limitation of the present work is that, although we have analysed the effects among export barriers, we have not considered an output related to export performance, as is the case for sales or export benefits. Therefore, future investigations should analyse the impact of barriers on an export indicator, such as the level of exports of the company. In this sense, research should take into consideration that Brazil is an economy that is currently undergoing a process of internationalization.

The second limitation of the present paper is that, to avoid making the study model too complicated, we did not take into account all the possible relationships between barriers. For instance, a confrontation of the barrier of human capital and the administrative barrier could have had an essential impact on the study. In subsequent investigations, this type of relationship between barriers could be addressed.

The size of the company was significant. Therefore, the company size could be analysed as a moderating variable. Furthermore, since the internationalization process is not always sequential (Osarenkhoe, 2009), other moderating variables could be considered. For instance, the effects of moderation could be analysed according to the specific internationalization strategy of a company, that is, whether the internationalization is taking place gradually or whether the company has been international since its incorporation (Uner et al., 2013). Following this line of research, one could address the extent to which human capital barriers, for instance, mediate the relationships between cultural barriers and product barriers and between administrative barriers and product barriers. Besides, other types of barriers, such as the accountability of local governments and an inadequate legal system, could be considered (Kumar et al., 2019). In addition, a more significant number of control variables could be added to the analysis model, for example the age of the company or its export experience. Finally, considering that Brazil is traditionally an exporter of commodities (Selwyn, 2013), it could be revealing to determine whether the export barriers are conditioned by the economic sector of the exporting company.

6ConclusionsThe determinants of and barriers to exporting are critical aspects analysed by the literature on firm internationalization (Krammer et al., 2018) as they largely decide the success or failure of internationalization. This paper has analysed the relationships between export barriers in an emerging economy country, Brazil, and has highlighted the interrelationships between barriers. In addition, it has verified the significant impact of the human capital barrier on the model. This leads us to conclude that, in emerging economies, as in developed economies (Pinho & Martins, 2010), export barriers interact by accumulating export obstacles. Therefore, overcoming the barriers, particularly the human capital barrier, would pave the way to exporting.