It is a patient with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia and a personal history of acute myocardial infarction, which is referred to our lipid unit for hypocholesterolemic treatment adjustment. Since he does not reach therapeutic goals with oral medication, he starts a treatment with fortnightly sessions of LDL-apheresis, which he keeps for 8 years. With the introduction and availability of PCSK9 inhibitors, a new treatment option is possible for this patient.

Se trata de un paciente con hipercolesterolemia familiar heterocigota y antecedentes de infarto agudo de miocardio, que es remitido a la unidad de lípidos de nuestro centro para ajuste del tratamiento hipocolesterolemiante. Dado que no alcanza los objetivos terapéuticos con tratamiento oral, comienza tratamiento con sesiones quincenales de aféresis de colesterol LDL, que mantiene durante 8 años. Con la introducción y disponibilidad de los inhibidores de la PCSK9, se presenta una nueva opción de tratamiento para este paciente.

We now have sufficient evidence to assert that lowering LDL cholesterol reduces the incidence of cardiovascular episodes.1 Until the appearance of PCSK9 inhibitors, many patients found it difficult to achieve therapeutic targets with the available pharmacological treatment, especially those with familial hypercholesterolaemia. In some of these, LDL apheresis was an effective alternative, although as a therapy it requires a high degree of availability on the part of the patient. Below, we present the case of a patient with familial hypercholesterolaemia in whom treatment with a PCSK9 inhibitor was found to be an adequate alternative to LDL apheresis.

Case reportThe case is that of a 50-year-old male patient with a history of familial hypercholesterolaemia being followed up in primary care and treated with atorvastatin 40mg/1 tablet per day. His medical history of interest also includes type 2 diabetes mellitus of seven years’ evolution (on treatment with metformin+sitagliptin 50/1000mg/12h, well controlled, with his latest HbA1c being 6.9%) and habitual alcohol consumption with an episode of delirium tremens in 2007. With regard to family history, his father died aged 71 of an acute myocardial infarction and he has a 56-year-old brother with dyslipidaemia of unknown origin and acute coronary syndrome.

In October 2007, the patient presented with an acute anteroseptal myocardial infarction and, following this episode, was referred for external consultations at the lipid clinic in our centre's endocrinology department for control of familial hypercholesterolaemia. The physical examination revealed arcus senilis, grade I obesity (BMI: 31.44kg/m2), weight 103kg, height 181cm and blood pressure 130/80mmHg.

In terms of complementary tests, a genetic diagnosis was carried out, finding that the patient had LDL receptor mutations compatible with p.Q92E and c.313+1G>C compound heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia. In the baseline analysis prior to starting cholesterol-lowering treatment with atorvastatin, he had the following lipid profile values: total cholesterol 513mg/dl, triglycerides 160mg/dl, HDL cholesterol 47mg/dl and LDL cholesterol 433mg/dl. In the latest available analysis, he had the following figures: total cholesterol 429mg/dl, triglycerides 119mg/dl, HDL cholesterol 40mg/dl and LDL cholesterol 365mg/dl.

Initially, ezetimibe 10mg per day and colesevelam 625mg/2 tablets/12h were added. The dose of atorvastatin was not increased as the patient reported myalgia with doses above 40mg/day. He also reported myalgia with other statins tried previously, including rosuvastatin.

Nevertheless, before the following visit the patient presented with a new episode of acute myocardial infarction. This posed the problem of a patient in secondary prevention with a need for significant LDL cholesterol reduction in order to achieve therapeutic targets. For this reason, the haematology department was contacted and, together with them, LDL apheresis sessions were scheduled every 14 days.

With this therapy, the patient maintained pre-apheresis LDL cholesterol figures around 127–165mg/dl and post-apheresis figures around 45–53mg/dl. This regimen was continued together with the oral treatment as before (atorvastatin, ezetimibe and colesevelam) for eight years, with good evolution and no new cardiovascular events.

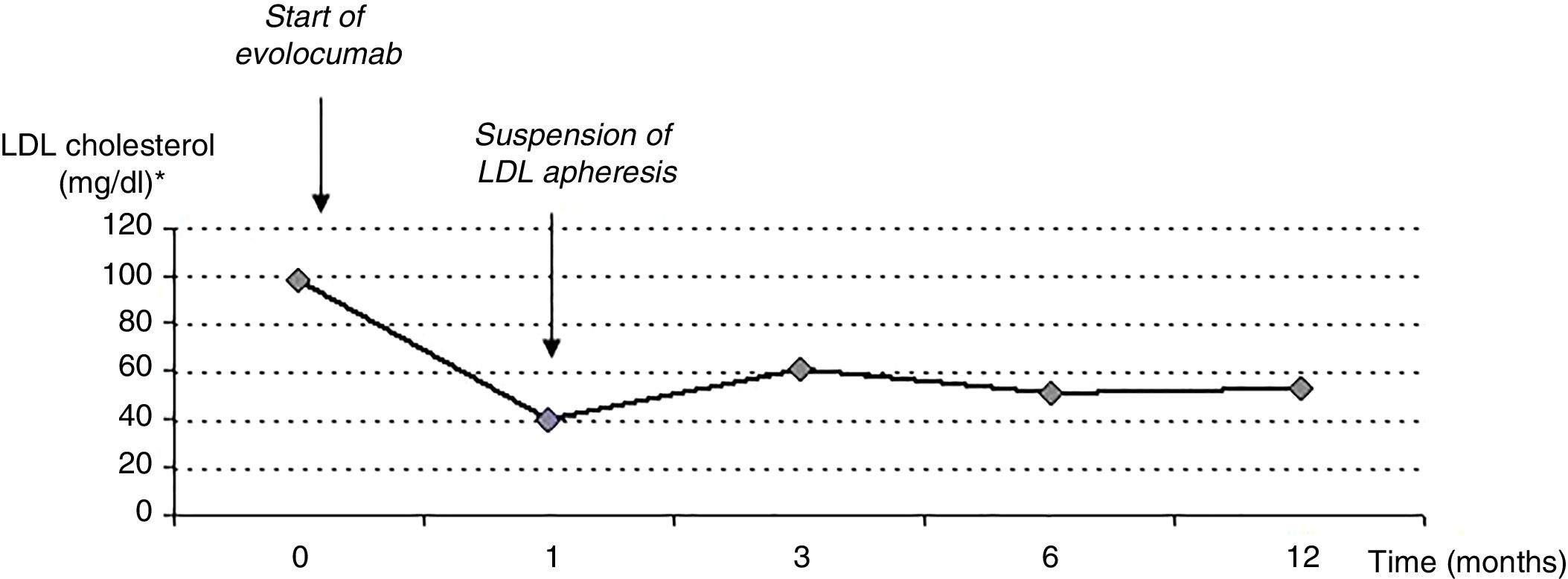

In December 2016, PCSK9 inhibitors had become available as a cholesterol-lowering treatment, and he was prescribed evolocumab 140mg every two weeks. His LDL cholesterol figures reduced with this treatment, and one month later his LDL cholesterol figures were 47mg/dl pre-apheresis and 26mg/dl post-apheresis. Given the good evolution, the decision was made to suspend the LDL apheresis sessions.

Thus, the patient continued treatment with: evolocumab 140mg every two weeks, atorvastatin 40mg/day, ezetimibe 10mg/day and colesevelam 625mg/2 tablets/12h.

Over the subsequent months the lower LDL cholesterol figures were maintained, with values between 51 and 61mg/dl, within the desirable therapeutic targets for the patient. This is maintained at one year from the start of treatment with the PCSK9 inhibitor, with total cholesterol levels of 101mg/dl, LDL cholesterol 51mg/dl, HDL cholesterol 51mg/dl and triglycerides 53mg/dl. The evolution of the LDL cholesterol levels is shown in Fig. 1.

The patient is clinically well with no adverse reactions to the treatment and no new cardiovascular episodes. Moreover, he subjectively reports being very satisfied with the treatment and that his quality of life has improved through not having to make fortnightly visits to the hospital for LDL apheresis, which allows him to more easily fit the treatment around his work and personal life. The remaining cardiovascular risk factors are also well-controlled, maintaining an HbA1c of 6.4% and blood pressure within normal limits.

DiscussionThe relationship between cardiovascular disease and high LDL cholesterol figures is clearly established. Some patients, especially those with familial hypercholesterolaemia, do not achieve the desirable therapeutic targets for LDL cholesterol with the oral treatment available, either due to intolerance to it or insufficient efficacy.2

LDL apheresis allows LDL cholesterol to be reduced by at least 60% and is therefore an efficacious therapeutic alternative in these patients.3,4 However, LDL apheresis treatment requires a high degree of availability on the part of the patient, as each apheresis session lasts 3–5h and they must take place every 7–14 days.5 Moreover, it can only be performed in certain specialised centres.4

We now have available new treatments, PCSK9 inhibitors (alirocumab or evolocumab), that when combined with statins have demonstrated LDL cholesterol reductions similar to those achieved with LDL apheresis.6 Moreover, treatment with PCSK9 inhibitors achieves a more constant reduction in LDL cholesterol, as the effect of apheresis is cyclical between sessions.7 This treatment also offers a better quality of life for the patient, avoiding numerous hospital visits. It is a well-tolerated and safe treatment, for which, as yet, few side effects have been described, and none of them severe.

For all of these reasons, the introduction of treatment with PCSK9 inhibitors could successfully reduce the frequency of LDL apheresis sessions or even be an alternative to apheresis sessions in many patients,2,7,8 as has occurred in our patient's case.

ConclusionTo conclude, we can affirm that treatment with PCSK9 inhibitors is efficacious, well-tolerated, safe and offers a good quality of life for patients. They represent an important advance in the treatment of hypercholesterolaemia, as they allow apheresis sessions to be reduced or replaced entirely in patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia, alone or in combination with other oral treatments.

Conflicts of interestThe author declares that she has no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Perelló Camacho E. Inhibidores de la PCSK9: una nueva mejora para la salud. Clin Investig Arterioscler. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arteri.2018.11.001