The food atopy patch (APT) test has been used in previous studies to help the diagnosis of non-IgE mediated food allergies (FA). The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of different cow's milk APT preparations to predict oral tolerance in children with previous non-IgE-mediated cow's milk allergy (CMA) diagnosis.

MethodsThirty-two patients non-IgE-mediated CMA diagnosed by oral food challenge (OFC) were enrolled to perform APT with three different cow's milk preparations (fresh, 2% in saline solution, 2% in petrolatum) and comparing with a new OFC after at least three months of diet exclusion.

ResultsOnly six (18.7%) subjects presented positive OFC to cow's milk. No differences in gender, onset symptoms age, OFC age, Z-score, and exclusion period were found between positive and negative OFC patients. Preparations using fresh milk and powdered milk in petrolatum presented sensitivity equal to zero and specificity 92.3% and 96.1%. The preparation using powdered milk in saline solution showed sensitivity and specificity of 33.3% and 96.1%. Two patients presented typical IgE symptoms after OFC.

ConclusionCow's milk APT presented a low efficacy to predict tolerance in patients with previous non-IgE-mediated CMA and should not be used in clinical routine. The presence of typical IgE reactions after OFC hallmark the necessity of previous IgE-mediated investigation for this patient group.

Food allergy (FA) is an adverse immune response that occurs reproducibly on exposure to a given food.1,2 FA may be classified according to the immunological mechanism involved: IgE mediated in which the reaction generally occurs in the first two hours after food exposure and is mediated by Immunoglobulin E (IgE); non-IgE mediated with symptoms that usually occur hours or days after food exposure and is associated with a cellular response; and mixed that involves both mechanisms.1–4

Non-IgE-mediated gastrointestinal food allergies are responsible for an unknown proportion of FA and include food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES) and food protein-induced allergic proctocolitis (FPIAP). Another manifestation less common is food protein-induced enteropathy (FPE).1,2,5–8 The most prominent clinical characteristics of FPIES are repetitive emesis, pallor, and lethargy; chronic FPIES can result in failure to thrive. FPIAP presents with bloody stools in well-appearing young breast-fed or formula-fed infants. Features of FPE are diarrhoea, malabsorption, protein-losing enteropathy, hypoalbuminaemia, and failure to thrive.1,2,5–8

Cow's milk allergy (CMA) is the food most implicated with non-IgE FA in infants as seen in IgE-mediated disease. Non-IgE FA have a favourable prognosis; the majority tolerate the food reintroduction by one year in patients with FPIAP and a little late in FPIES patients.1,2 While the use of specific IgE and the skin-prick test to foods are used for IgE-mediated FA, there is no consensus around laboratorial evaluation for non-IgE-mediated FA.3,4,9,10 The food atopy patch test (APT) has been used by many researchers as a tool to help the diagnosis of non-IgE-mediated food allergies but controversial results have been found in previous studies credited to different standardisation protocols.1,2,11,12

Even considering the favourable prognosis, the existence of one diagnose tool could improve the diagnosis and support the best moment to reintroduce the involved food in the diet.1,2 The aim of this study was to evaluate the accuracy of cow's milk APT using different preparations for patients previously diagnosed non-IgE-mediated gastrointestinal cow's milk allergy to predict tolerance to this food.

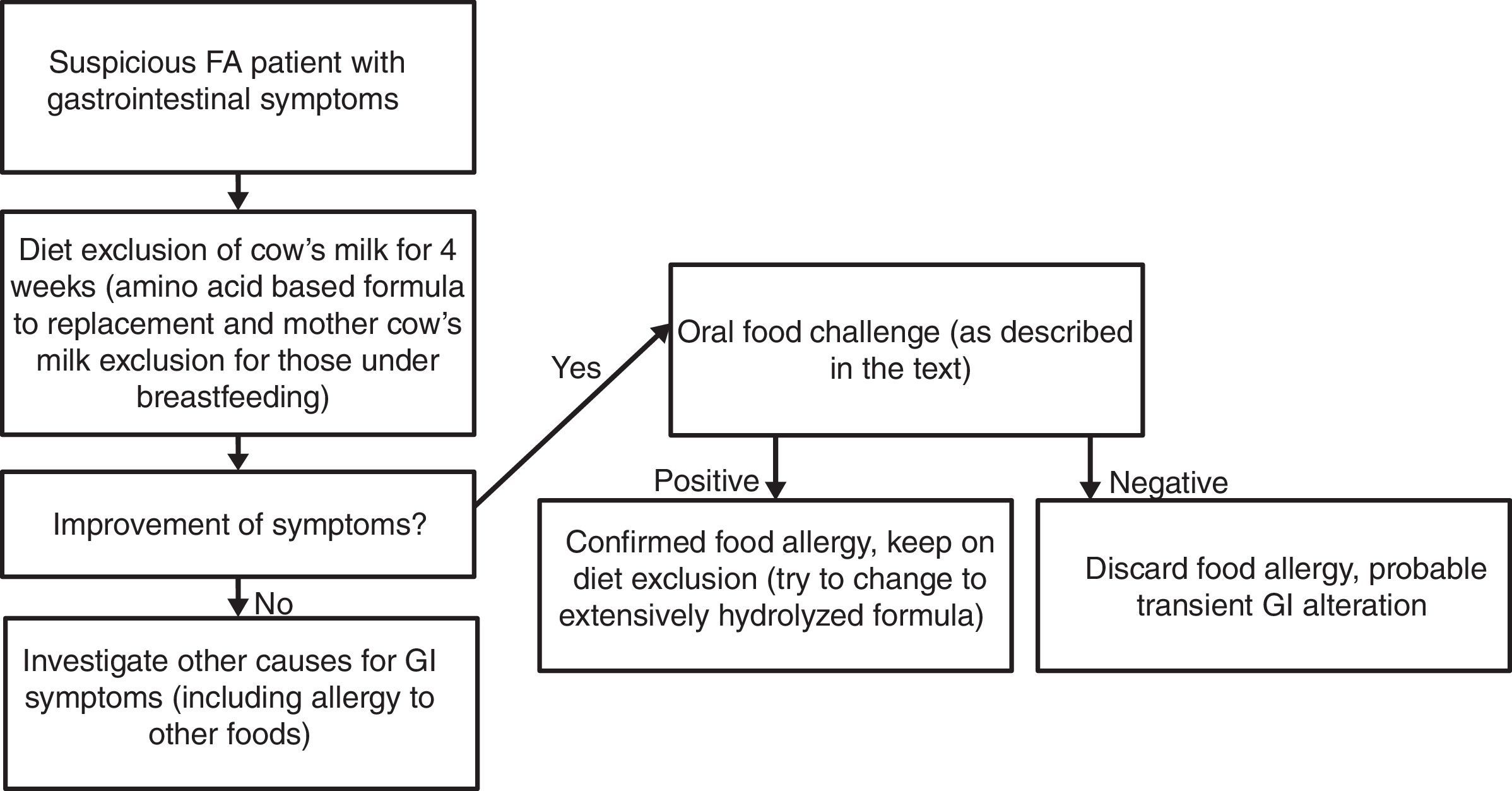

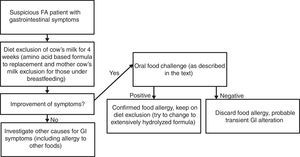

Materials and methodsPatient selectionSubjects were recruited from the Food Allergic Outpatient Clinic at Clinical Hospital of Universidade Federal de Uberlândia (Uberlandia, Brazil). All children enrolled in the study presented non-IgE-mediated CMA diagnosis classified as food protein-induced allergic proctocolitis and/or food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES) performed previously using the cow's milk oral food challenge (OFC) to confirm as shown in Fig. 1. We excluded patients with non-IgE-mediated CMA diagnosis without previous confirmatory OFC. All subjects had been on cow's milk diet exclusion for at least three months at the moment of participation in the study.

The main symptoms presented at diagnosis were bloody stools in 21 (65.6%), abdominal pain/excessive cramps in 19 (59.4%), diarrhoea in 18 (56.2%), and vomits in 18 (56.2%). FPIAP were diagnosed in 9 (28.1%) while 12 (37.6%) were diagnosed as chronic FPIES. Another 11 (34.3%) subjects initially presented features of FPIAP but later presented other characteristics and received the FPIES diagnosis.

Study protocolThe protocol was carried out at the Day Unit, under the direct supervision of the medical staff with all the equipment and material required for the treatment of possible allergic reactions that could occur during the procedure. The cow's milk APT was performed using fresh cow's milk, 2g of powdered skimmed cow's milk with 2g of petrolatum vehicle, and 2g of powdered skimmed cow's milk with 2mL of isotonic saline solution vehicle.12,13 These preparations were attached to 8-mm Finn chambers, which were adhered to the upper region of the patient's back and removed after 48h, and the reading was performed 24h after. The same researcher performed and read all APTs following the technique described previously.13

In-patient OFCs were performed by administering increasing doses of cow's milk based infant formula (10mL, 20mL, 30mL, and 40mL) every 20min for all patients and were observed in hospital per four hours. After discharge, one patient was receiving exclusively breastfeeding from mother under cow's milk diet exclusion and we only returned the cow's milk to the mother's diet; all other patients received cow's milk based formula as a replacement to extensively hydrolysed or amino-acid based formula. Patients’ parents were instructed to contact the research staff if symptoms started and were evaluated at the allergy unit. Those patients without complaints were evaluated at the allergy unit twice after OFC (1 and 4 weeks after OFC) to be sure that symptoms did not return. The OFC was considered positive if the patient restarted sustained gastrointestinal symptoms in the period. If the patient presented with no clinical manifestation of food allergy, the OFC result was considered negative.12

Ethics statementAll human procedures were performed with written consent from the next of relatives, caretakers, or guardians on behalf of the children involved in the study. The Bioethics Committees from Universidade Federal de Uberlandia (Uberlandia, Brazil) approved all procedures.

Statistical analysisThe Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to determine whether variables were normally distributed. For continuous variables, groups were compared using the unpaired t test. The Fisher exact tests were used for categorical variables. The level of significance for all statistical tests was two-sided, P<0.05. Sensitivity, specificity, negative predictive value (NPV), positive predictive values (PPV) were calculated considering OFC as the gold standard. All analyses were conducted using Graph Pad Prism 5.0 (La Jolla, CA, USA).

ResultsThirty-two subjects were enrolled, the mean age was 229.7 days (SD: 135.37) and 21 (65.6%) were males. The mean onset symptoms age was 71.1 days (SD: 64.74), the mean z-score height per age was −0.16 (SD: 1.21), and the mean cow's milk exclusion was 143.7 days (SD: 55.47).

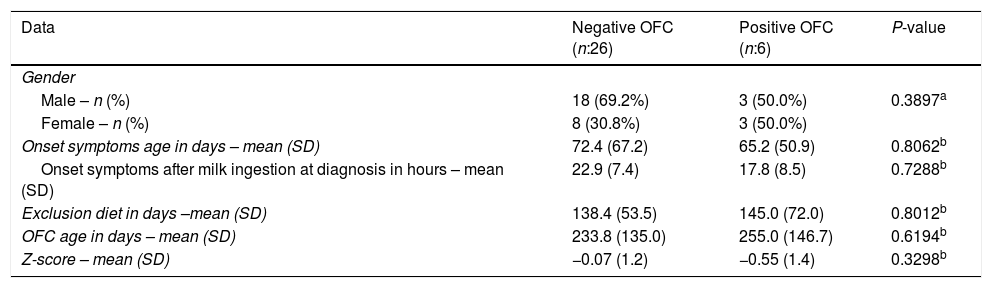

From 32 patients, only six (18.7%) presented positive OFC for cow's milk. Two of them presented urticarial hives following the OFC. There were no significant differences regarding onset age of symptoms, Z-score, OFC performance age or cow's milk exclusion between OFC negative and OFC positive group (Table 1). The data from all subjects with positive TPO are shown in Table 2.

Clinical features of patients with positive and negative cow's milk oral food challenge (OFC).

| Data | Negative OFC (n:26) | Positive OFC (n:6) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male – n (%) | 18 (69.2%) | 3 (50.0%) | 0.3897a |

| Female – n (%) | 8 (30.8%) | 3 (50.0%) | |

| Onset symptoms age in days – mean (SD) | 72.4 (67.2) | 65.2 (50.9) | 0.8062b |

| Onset symptoms after milk ingestion at diagnosis in hours – mean (SD) | 22.9 (7.4) | 17.8 (8.5) | 0.7288b |

| Exclusion diet in days –mean (SD) | 138.4 (53.5) | 145.0 (72.0) | 0.8012b |

| OFC age in days – mean (SD) | 233.8 (135.0) | 255.0 (146.7) | 0.6194b |

| Z-score – mean (SD) | −0.07 (1.2) | −0.55 (1.4) | 0.3298b |

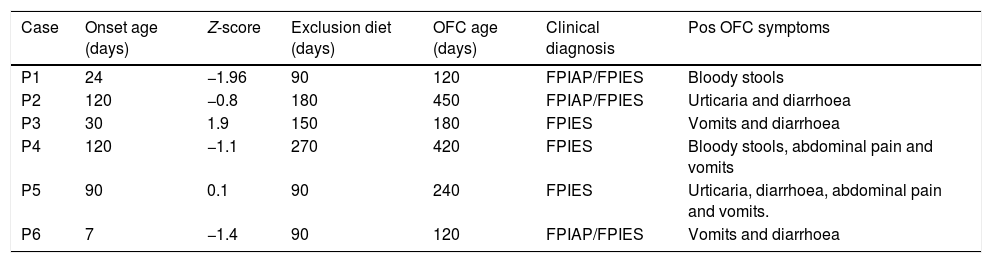

Oral food challenge (OFC) positive challenge patients features.

| Case | Onset age (days) | Z-score | Exclusion diet (days) | OFC age (days) | Clinical diagnosis | Pos OFC symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 24 | −1.96 | 90 | 120 | FPIAP/FPIES | Bloody stools |

| P2 | 120 | −0.8 | 180 | 450 | FPIAP/FPIES | Urticaria and diarrhoea |

| P3 | 30 | 1.9 | 150 | 180 | FPIES | Vomits and diarrhoea |

| P4 | 120 | −1.1 | 270 | 420 | FPIES | Bloody stools, abdominal pain and vomits |

| P5 | 90 | 0.1 | 90 | 240 | FPIES | Urticaria, diarrhoea, abdominal pain and vomits. |

| P6 | 7 | −1.4 | 90 | 120 | FPIAP/FPIES | Vomits and diarrhoea |

FPIAP: food protein-induced allergic proctocolitis.

FPIES: food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES).

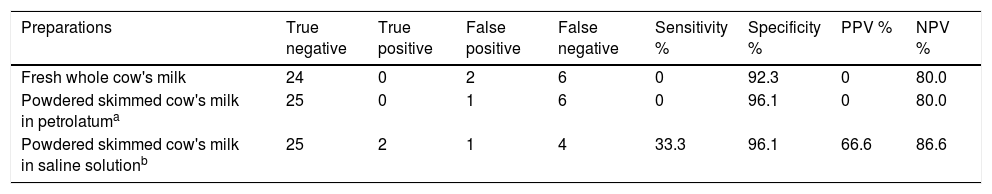

Table 3 shows sensitivity, specificity, NPV, and PPV. The preparations using powdered skimmed cow's milk in petrolatum vehicle and fresh cow's milk were not able to detect patients with positive OFC, resulting in sensitivity zero. The same preparations presented one and two false positives resulting in specificities of 96.1% and 92.3%, respectively. Both preparations resulted in PPV values equal zero and NPV 80.0%.

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV) of cow's milk atopy patch test compared with oral food challenge.

The APT preparation using powdered skimmed cow's milk in isotonic saline solution vehicle presented two true positive tests resulting in sensitivity 33.3% and one false positive test with subsequent specificity 96.1%, with 66% of PPV and 86.2% of NPV.

DiscussionFood APT is a relatively new diagnostic tool used to identify FA, however, most studies evaluate its helpfulness for FA diagnosis on atopic dermatitis patients.13–17 Few studies have been published evaluating the role of APT for foods on patients with gastrointestinal manifestations associated with non-IgE-mediated FA as FPIAP and FPIES.12,18–25

In 2006, an initial study on the use of food APT in FPIES using milk, egg, soy, rice and oat showed 100% of sensitivity and 71% of specificity, placing APT as a promising tool for non-IgE-mediated FA.18 One year late, another study evaluating APT to milk, egg and soy found a lower sensitivity (64.5%) and an increased specificity (95.8%) on patients with gastrointestinal non-IgE-mediated FA.19 In contrast, one 2012 study after performing APTs paralleling with 102 OFC for FPIES patients with different foods (milk, soy, rice and oat) showed totally different results, demonstrating 11.8% of specificity and 85.7% of sensitivity.20

Cudowska et al. studied the use of APT exclusively on patients with non-IgE-mediated CMA with gastrointestinal manifestations and showed 77% sensitivity and 73% specificity.21 Also studying APT and non-IgE-mediated CMA on Italy, Canani et al. found sensitivity of 53.8% and specificity of 97.8%.22 In the same study, they also calculated the sensitivity and specificity using only erythema with slight infiltration and/or few papules as positive (equivalent to ++ by European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis) and found an increment in sensitivity to 66.7% and a reduction in specificity to 84.1%.22 In our study, we did not find differences using ++ or +++ as a positive result for APT.

Other paper studied the APT efficacy to verify tolerance for non-IgE-mediated CMA patients performed by the same group in Italy found sensitivity of 67.9% and specificity of 88.3%.23 However, two other recent publications with larger number of patients showed similar efficacy to our study, both with sensitivity of 21% and with specificity of 73% and 91%.24,25 In a previous study of our group with FPIAP suspicious children, no patients presented positive APT resulting in a sensitivity zero and 100% of specificity.12 The large variation in APT results for non-IgE-mediated demonstrated by numerous studies could be credited to methodological differences, mainly the different preparations of food used inside the chambers and the reading techniques.3,7,13

In our study, in order to solve the problem created by different APT methods in the previous studies and produce more reliable results, we utilised three different cow's milk preparations previously used in other studies.18–25 We also included the medical visits to guarantee that symptoms were really related to the OFC and not the consequence of other medical issues such as viral diseases, common at our patients’ age. The execution of all APT readings by the same researcher may have contributed to the matching data.3,11

The OFC on patients with non-IgE-mediated CMA in the present cohort found two patients with urticarial manifestation. The finding of specific IgE on patients with FPIES was described previously, varying from 4% to 30% of patients and could be a marker for persistent disease.1 Although the majority of the children who have food-specific IgE antibodies keep the FPIES phenotype; up to 35% of such children with cow's milk FPIES could experience IgE-mediated food allergy symptoms to the food that previously induced an FPIES reaction.26,27

The potential limitation in the present study is probably the number of positive OFC at the moment of performing the food APT. However, it is important to remember that all patients had a previous positive OFC to confirm the food allergy and that is the natural history of non-IgE-mediated FA with a favourable prognosis.3

The controversial results from different studies show the necessity to improve the understanding of non-IgE-mediated FA and food APT pathophysiological mechanisms.3 The high perception of food allergy in children among parents is associated with unnecessary diet exclusion, which could result in a negative impact in the childhood development, increasing the costs to buy alternative and more expensive foods, and reducing the quality of life and social family relations associated with restrictive measures adopted by families to avoid the contact with food implicated with allergy.1–8 These associated factors require further studies in an attempt to find a laboratory marker for non-IgE-mediated FA.

In conclusion, according to our data, the preparation using 2g of powdered skimmed cow's milk with 2mL of isotonic saline solution vehicle was slightly superior than others tested. However, even this preparation failed to identify 66.7% of patients with positive OFC and consequently, the use of APT for non-IgE-mediated CMA in the clinical routine remains not recommended. The OFC should be used in this regard for diagnosis and for tolerance acquisition. The evaluation of IgE by skin-prick test or by specific IgE measure prior to the OFC performance for tolerance, especially in FPIES, could be useful to identify those children with elevated risk to present typical IgE-mediated FA symptoms.

Ethical disclosuresConfidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

FundingCoordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (Capes) and Brazilian Agency and Fundação de Apoio a Pesquisa de Minas Gerais (Fapemig).

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.