Background: The Emotional Intelligence theory has evolved from the respective definitions of intelligence and emotion. Emotional Intelligence is a fundamental competence for Nursing professionals because it allows developing effective therapeutic relationships, facilitates interaction with other professionals, acts as a significant predictor of conflict management, and is related to a reduction in stress due to overload and work schedules or avoidance behaviours that can affect Nursing care quality but their training is not sufficiently integrated into the training curricula of health professions son the study’s aim is to evaluate the change in Nursing students' perception regarding Emotional Intelligence after carrying out clinical practices in different care services.

Materials and methods: A longitudinal and observational study was carried out at differents Spain's universities. 149 students were included in the study, recruited through a accidental sampling in four Spanish universities. The study investigates the emotional change produced by clinical practices through the TMMS-24 questionnaire. Other sociodemographic and academic variables were collected and the Nursing students' stressors in clinical practices by KEZKAK questionnaire and the Nursing students' perceptions of the instructor's care by S-NSPIC, because they have demonstrated their influence in the process.

Results: The sample consisted of 88.5% were women (n=131) and 11.5% men (n=17) with a mean age of 23.36 ±4.69 years old. The perception of Emotional Intelligence obtained adequate ranges and it increases after clinical practices (p<0.001), a statistically significant change (p=0.031) is observed in Emotional Intelligence according to the type of service in which they carry out the practices. Highlighting the Operating Room as the unit in which the greatest change occurs (12.67±3.79) when compared to the special care units, where it is lower (0.50±7.44). Differences are also observed according to duration of the clinical practices, increasing when the periods of practices are longer.

Conclusions: Acquisition of Emotional Intelligence depends on the clinical service in which the students carry out their internships, their duration and the relationships they develop with the tutors. These criteria must be taken into account for the creation of study plans that favour both the increase in knowledge and social and emotional skills, guaranteeing the students' incorporation into the labour market with all possible tools.

Antecedentes: La teoría de la Inteligencia Emocional ha evolucionado a partir de las respectivas definiciones de inteligencia y emoción. La Inteligencia Emocional es una competencia fundamental para los profesionales de Enfermería porque permite desarrollar relaciones terapéuticas efectivas, facilita la interacción con otros profesionales, actúa como un predictor significativo de la gestión de conflictos y se relaciona con una reducción del estrés por sobrecarga y horarios de trabajo o conductas de evitación que pueden afectar la calidad de la atención de enfermería pero su formación no está suficientemente integrada en los planes de estudios de las profesiones sanitarias por lo que el objetivo del estudio es evaluar el cambio en la percepción de los estudiantes de Enfermería sobre la Inteligencia Emocional tras de la realización de prácticas clínicas en diferentes servicios de atención.

Material y métodos: Se realizó un estudio longitudinal y observacional en diferentes universidades españolas. Se incluyeron en el estudio 149 estudiantes, reclutados mediante muestreo accidental en cuatro universidades españolas. El estudio investiga el cambio emocional producido por las prácticas clínicas a través del cuestionario TMMS-24. Se recogieron variables sociodemográficas y académicas, los estresores en las prácticas clínicas mediante el cuestionario KEZKAK y las percepciones sobre el cuidado del instructor mediante el S-NSPIC ya que han demostrado su influencia en el proceso.

Resultados: La muestra estuvo compuesta por un 88,5% mujeres (n=131) y un 11,5% hombres (n=17) con una edad media de 23,36 (DE:4,69) años. La percepción de Inteligencia Emocional obtuvo rangos adecuados y aumenta después de las prácticas clínicas (p<0,001), se observa un cambio estadísticamente significativo (p=0,031) en Inteligencia Emocional según el tipo de servicio en el que se realizan las prácticas, destacando el Quirófano como la unidad en la que se produce el mayor cambio (12,67±3,79) en comparación con las unidades de cuidados especiales, donde es menor (0,50±7,44). También se observan diferencias según la duración de las prácticas clínicas, incrementándose cuanto más largos son los periodos de las prácticas.

Conclusiones: La adquisición de Inteligencia Emocional depende del servicio clínico en el que los estudiantes realizan sus prácticas, su duración y las relaciones que desarrollan con los tutores. Estos criterios deben tenerse en cuenta para la creación de planes de estudio que favorezcan tanto el incremento de conocimientos como de habilidades sociales y emocionales, garantizando la incorporación de los estudiantes al mercado laboral con todas las herramientas posibles.

Clinical internships are defined as undergraduate nursing students’ experiences in the clinical environment to learn practical skills, apply nursing knowledge, and experience the professional behaviors necessary to achieve the essential competencies of novice nurses.1 This definition does not include clinical simulation, which is used to prepare students through role-play and, although it can prepare students for the clinical context; there is no comparison to the learning that comes from managing patients in a real clinical context.2 In this sense, therefore, it is considered that experiences in clinical practices are not only important, but essential for the development of the nursing identity, the motivation to continue in the degree and the obtaining of successful results.3

In Spain, the Nursing Degree is regulated by the Resolution of February 14 (2008) which establishes, 4 courses that involve the acquisition of 240 credits from the European Transfer System (ECTS). The supervised internships comprise 84 ECTS and allow the integration of both basic and specific knowledge of the profession and the development of skills for carrying out nursing care.4

Emotions are essential for the exercise of the Nursing profession.5 Nursing professionals establish and maintain relationships within environments marked by significant emotional load, in which knowing how to manage them is essential for holistic patient care.6 Damasio was one of the first researchers to assert, and to empirically verify, that emotions are essential in any judgment and that they assist in the reasoning process, instead of disturbing it, as was the common belief.6

Management of emotions is carried out through Emotional Intelligence (EI), which is a psychological construct proposed to the scientific community at the end of the 20th century.7 It is a characteristic that facilitates interpersonal relationships because it allows people to be aware of their own emotions, understand them, manage them in themselves and in others, and use them for better reasoning so having EI would help students to be successful in their interpersonal relationships associated with learning, by favouring the processing of emotional information.6

The skill model promoted by Salovey and Mayer8 defines EI as “the ability to perceive, assess and express emotions, access and process emotional information, generate feelings, understand emotional knowledge and regulate emotions”; it states that having EI depends on the ability to process emotional information and use basic skills related to emotions. Therefore, EI can be learned, increases with age, and is predictive of how emotional processing contributes to success in life.

Although EI has been studied for years, Nursing studies are recent and scarce. From the published reviews,9,10 it seems that EI improves important aspects for the profession, such as those associated with inter- and intra-personal relationships, which are the basis of the interactions with patients, their families, colleagues, teamwork, professional satisfaction and self-care. These conclusions are supported by various authors11 who advocate that EI is a fundamental competence for Nursing professionals because it allows developing effective therapeutic relationships, facilitates interaction with other professionals, acts as a significant predictor of conflict management, and is related to a reduction in stress due to overload and work schedules, burnout, death anxiety or avoidance behaviours that can affect Nursing care quality. Despite these results, their training is not sufficiently integrated into the training curricula of health professions9 which causes an increase in insecurity, low self-esteem, irritability, depression, somatic disorders, sleep disorders and physical and mental exhaustion in students.9,12 This problem increases when the students, in their clinical internship, have to face emotionally difficult situations.6 Some examples are the Intensive Care Unit (ICU), due to the severity of the patients admitted to it; the emergency services, due to fast and stressful attention; and Oncology services, due to the emotional and family component it has and the proximity to death.13 During this learning, each student has a reference nurse-tutor who guides them in knowledge acquisition; this nurse-tutor should enhance their pupils' EI and teach them how to react to emotionally difficult situations, as aware Nursing students pay attention and regulate emotions moderately well and are better able to resist, cope with, and recover from stress.14

Given the above, this research intends to evaluate the change in Nursing students' perception regarding EI after carrying out clinical internship in different care services Furthermore, the aim is to study the factors that influence its modification such as sociodemographic variables, the stressors of clinical practices and the caring relationship expressed by the instructor. This paper provides information that is necessary to improve the training curricula and ensure that future Nursing professionals have the emotional management tools that allow reducing the burnout and dropout rates currently suffered by this group.

Material and methodsDesignA quasi experimental pre and post study was carried out at four Spanish Universities where the exposure factor was the clinical internship to which the students were exposed as part of their training curriculum during the 2021-2022 academic year. Information was collected before and after each round of clinical internship following the standards established in the 17th declaration of Strengthening the Reports of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE).

ParticipantsThe sample size required for a bilateral contrast of paired means was calculated using the GRANDMO v.7.2® calculator to detect a statistically significant difference equal to or greater than 2 units, accepting an alpha risk of 0.05 and a beta risk of 0.2 with a standard deviation (SD) of 7 units and a loss rate of 15%, resulting in 114 participants. However, in order to achieve an adequate representation of the care units, it was decided to increase the sample size to 149 students. Finally, there were no losses to follow-up, so the sample size was larger than calculated.

- •

Data collection procedures

The students who started their clinical internships were contacted through their institutional email, previously provided by the internship coordinators of each university. They informed that the participation was voluntary and would not influence the course’s qualification and informed consent were accepted. In order to reduce follow-up losses, the students were provided with a report of their previous EI perception (Annex 1) encrypted by means of a password that they obtained after answering the second questionnaire at the end of the clinical internship.

- •

Instruments

The study investigates the emotional change produced by clinical internship, this is achieved by evaluating EI in each student before and after clinical practices through the TMMS-24 questionnaire, which is the main variable. The Spanish version of TMMS was designed by Salovey and Mayer15 and translated into Spanish by Fernández-Berrocal et al.,16 which evaluates each person's knowledge about their own emotional skills. It contains 24 items that are answered using a five-point Likert scale and report on three factors: emotional perception (items 1 to 8), ability to feel and express one's own feelings adequately; emotional understanding (items 9-16), perceived ability to understand and discriminate feelings; and emotional regulation (items 17-24), perceived ability to properly regulate moods, repair negative states and prolong positive ones. For the evaluation, each of the items that comprise the factors is added up. This instrument shows adequate psychometric characteristics (Cronbach alpha=0.95) in Spanish samples.

Other independent and secondary variables were collected like age (calculated via date of birth and grouped later), gender (male and female), university centre (EUECR-UAM, UCM, EUECR-S and Private), course (2nd, 3rd, 4th) internship centre (Primary Care Centre and Concerted, private or public Hospital), internship shift (morning or afternoon), internship assistance service (Primary Care Centre, specialty, medical, surgical, paediatrics and operating room), evaluation system (reflective diaries (RDs)) and the combination of RDs with other types of work such as critical reading (CR), Nursing Care Process (NCP) and clinical cases (CCs) and turnover start and end date that allowed us to know the duration of the internship in the service. The Nursing students' stressors in clinical practices were studied by KEZKAK questionnaire17 that is composed of 41 items, answered through a 4-point Likert scale, rating how much the described situation worries them from 0 (‘Not at all’) to 3 (“A lot”), the total score of the questionnaire (123 points) reveals the extent to which students find clinical practice stressful in general, presenting an overall internal consistency (Cronbach’s Alpha) of 0.95. Finally, the Nursing students' perceptions of the instructor's care defined as those verbal and non-verbal caring actions based on the theory of caring, demonstrated by the clinical instructor and perceived by nursing students to facilitate student learning about the development of the professional role, a caring attitude, clinical confidence , clinical competence and interpersonal caring interactions. Instructor care is a fundamental facilitator of clinical education by S-NSPIC that has been translated and adapted into Spanish by Romero-Martin et al.18 and it consists of 29 items answered using a Likert scale from 1 to 6, with a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.95.

- •

Data analysis

In the data analysis, some variables were recoded to facilitate the analysis without losing relevant information. Relative and absolute frequencies were calculated for the qualitative variables, and central tendency and dispersion measures were calculated for the quantitative variables, with 95% confidence intervals. Normality of the variables was verified using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and a paired hypothesis contrast was performed using the corresponding statistical tests, recognizing a statistically significant relationship when p-value<0.05. Likewise, the size or magnitude of the effect has been calculated through Cohen's D, whose interpretation is made through the absolute value of the coefficient obtained, so that values below 0.2 are considered a small effect, around 0.5 a medium effect, and more than 0.8 a large effect. Finally, a correlation and multiple linear regression analysis was performed between the main variables of the study. Data analysis was performed with the SPSS 26v® statistical program.

- •

Ethical considerations

This study was conducted applying the latest revision of the Declaration of Helsinki.19 Data treatment was confidential in accordance with Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the on Data Protection Council of April 27th, 2016. Likewise, the project was approved by the ethics committees of the participating universities.

Results- •

Characteristics of the sample

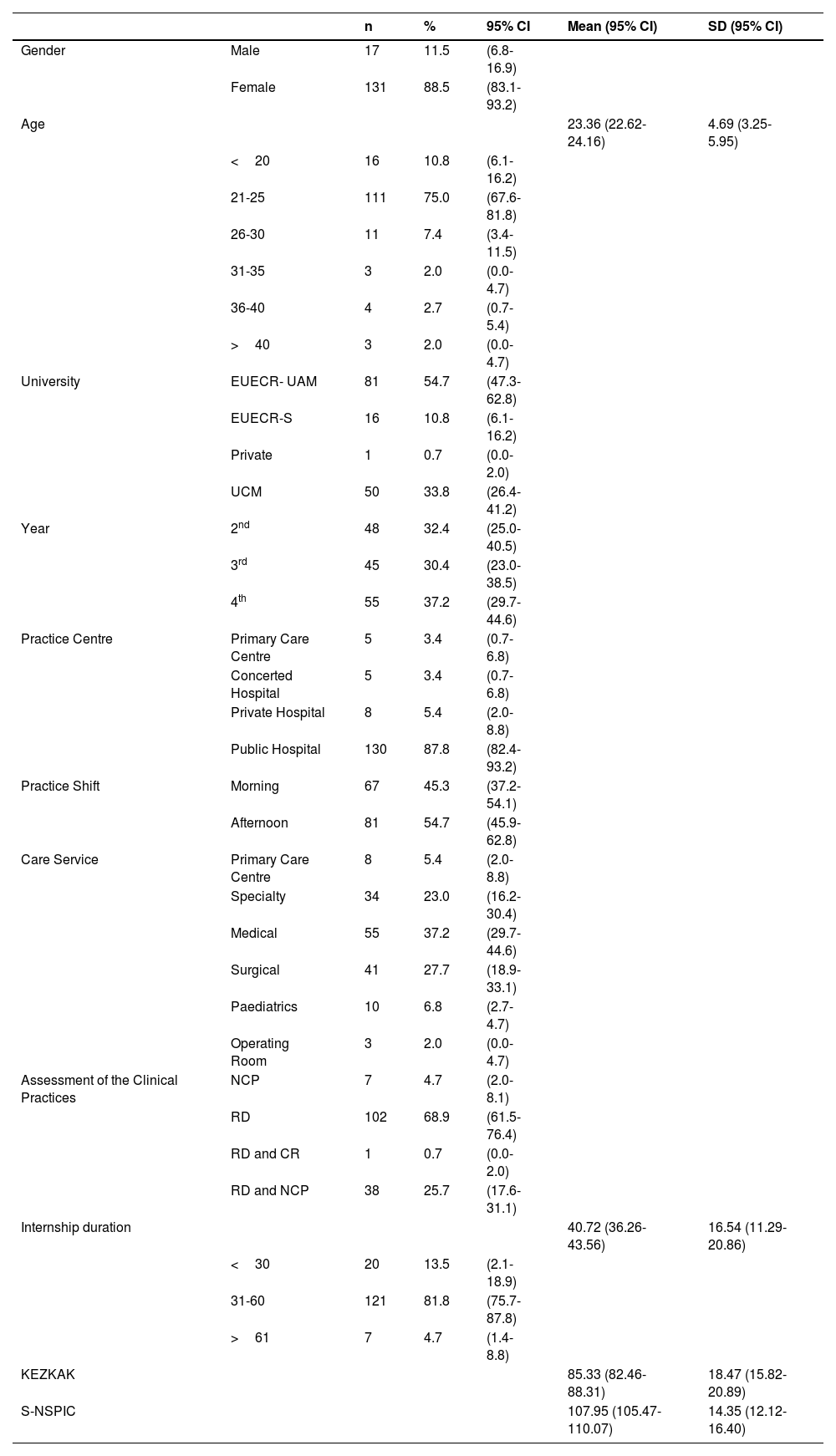

The sample consisted of 149 students attending the 2021-2022 academic year, of whom 88.5% were women (n=131) and 11.5% men (n=17) with a mean age of 23.36 ±4.69 years old (min. 20, max. 48), mostly from the EUECR-UAM which contributed 54.7% (n=81) of the students, followed from the UCM with 33.8% (n=50). The distribution by years was homogeneous with 32.4% (n=48) from 2nd year, 30.4% (n=45) from 3rd year and 37.2% (n=55) from 4th year, as was the case with the distribution by shift, where 45.3% (n= 67) attended classes in the morning and 54.7% (n=81) in the afternoon. Most of the students (87.8%; n=130) did their internships in public centres and in medical hospitalization services (37.2%; n=55) followed by surgical services (27.7%; n= 41), special services (23%; n=34), maternal and child services (6.8%; n=10) and Primary Care (5.4%; n=8). The students were mainly evaluated by means of reflective diaries (RDs) with 68.9% (n=102) and the combination of RDs with other types of work such as CR, NCP and CCs, with 0.7% (n=1), 24.3% (n=36) and 1.4% (n=2), respectively. The internship duration referred to was 40.72 ± 16.54 days (minimum of 10, maximum of 110), highlighting the high stress levels reported by the students at the beginning of the internship (85.3 ± 18.47) as well as an adequate relationship between students and clinical tutors (107.95 ± 14.35); further information can be found in Table 1.

- •

Change in EI after clinical practices

Demographic and academic characteristics of the sample.

| n | % | 95% CI | Mean (95% CI) | SD (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 17 | 11.5 | (6.8-16.9) | ||

| Female | 131 | 88.5 | (83.1-93.2) | |||

| Age | 23.36 (22.62-24.16) | 4.69 (3.25-5.95) | ||||

| <20 | 16 | 10.8 | (6.1-16.2) | |||

| 21-25 | 111 | 75.0 | (67.6-81.8) | |||

| 26-30 | 11 | 7.4 | (3.4-11.5) | |||

| 31-35 | 3 | 2.0 | (0.0-4.7) | |||

| 36-40 | 4 | 2.7 | (0.7-5.4) | |||

| >40 | 3 | 2.0 | (0.0-4.7) | |||

| University | EUECR- UAM | 81 | 54.7 | (47.3-62.8) | ||

| EUECR-S | 16 | 10.8 | (6.1-16.2) | |||

| Private | 1 | 0.7 | (0.0-2.0) | |||

| UCM | 50 | 33.8 | (26.4-41.2) | |||

| Year | 2nd | 48 | 32.4 | (25.0-40.5) | ||

| 3rd | 45 | 30.4 | (23.0-38.5) | |||

| 4th | 55 | 37.2 | (29.7-44.6) | |||

| Practice Centre | Primary Care Centre | 5 | 3.4 | (0.7-6.8) | ||

| Concerted Hospital | 5 | 3.4 | (0.7-6.8) | |||

| Private Hospital | 8 | 5.4 | (2.0-8.8) | |||

| Public Hospital | 130 | 87.8 | (82.4-93.2) | |||

| Practice Shift | Morning | 67 | 45.3 | (37.2-54.1) | ||

| Afternoon | 81 | 54.7 | (45.9-62.8) | |||

| Care Service | Primary Care Centre | 8 | 5.4 | (2.0-8.8) | ||

| Specialty | 34 | 23.0 | (16.2-30.4) | |||

| Medical | 55 | 37.2 | (29.7-44.6) | |||

| Surgical | 41 | 27.7 | (18.9-33.1) | |||

| Paediatrics | 10 | 6.8 | (2.7-4.7) | |||

| Operating Room | 3 | 2.0 | (0.0-4.7) | |||

| Assessment of the Clinical Practices | NCP | 7 | 4.7 | (2.0-8.1) | ||

| RD | 102 | 68.9 | (61.5-76.4) | |||

| RD and CR | 1 | 0.7 | (0.0-2.0) | |||

| RD and NCP | 38 | 25.7 | (17.6-31.1) | |||

| Internship duration | 40.72 (36.26-43.56) | 16.54 (11.29-20.86) | ||||

| <30 | 20 | 13.5 | (2.1-18.9) | |||

| 31-60 | 121 | 81.8 | (75.7-87.8) | |||

| >61 | 7 | 4.7 | (1.4-8.8) | |||

| KEZKAK | 85.33 (82.46-88.31) | 18.47 (15.82-20.89) | ||||

| S-NSPIC | 107.95 (105.47-110.07) | 14.35 (12.12-16.40) | ||||

EUECR- UAM: Red Cross Nursing School attached to Universidad Autónoma de Madrid.

EUECR-S: Red Cross Nursing School attached to Universidad de Sevilla.

UCM: Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

RD: reflective diaries.

NCP: nursing care processes.

KEZKAK: Stressors inherent to clinical practices.

S-NSPIC: Nursing students' perceptions about their instructor's caring behaviours.

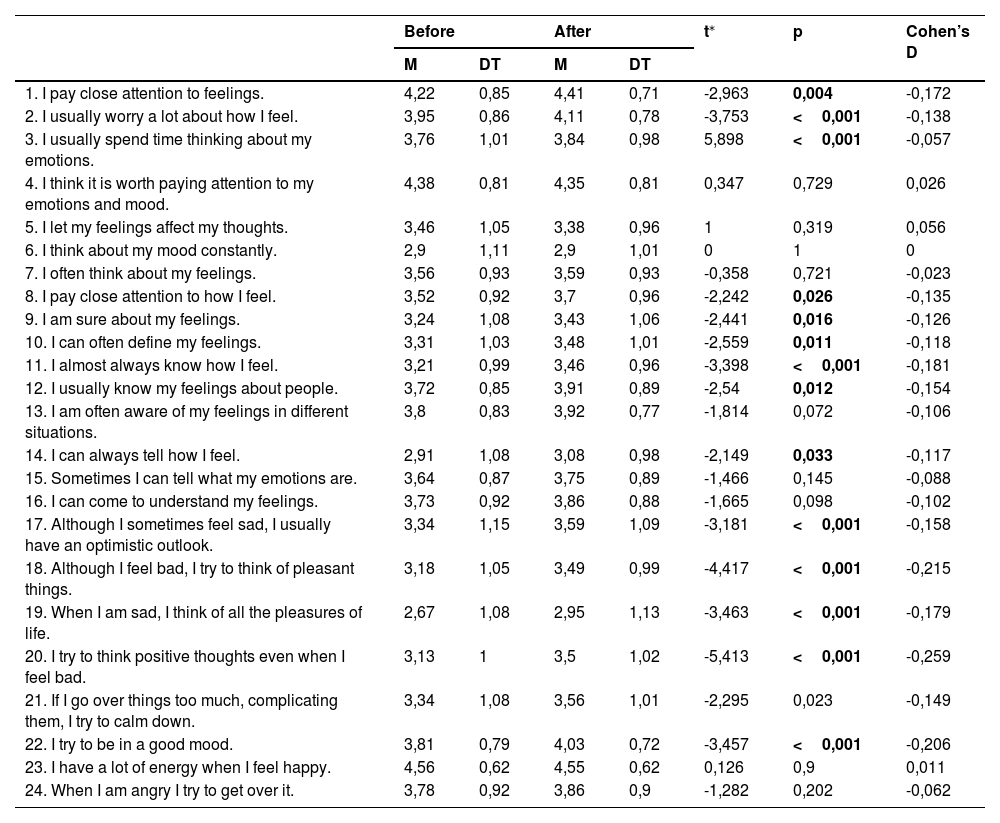

Table 2 shows the detailed analysis of TMMS-24, where an increase in scores is observed after the clinical practices with statistically significant differences in most items, except in item 6 (I think about my mood constantly), in which the mean score is maintained, and in items 4 (I think it is worth paying attention to my emotions and mood), 5 (I let my feelings affect my thoughts) and 23 (I have a lot of energy when I feel happy), in which it produces a reduction in its mean score after the practices. However, the magnitude of the effect found, measured through Cohen's D, shows small changes when it is below 0.2 in its absolute value.

Results of the TMMS-24 items before and after the clinical practices.

| Before | After | t⁎ | p | Cohen’s D | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | DT | M | DT | ||||

| 1. I pay close attention to feelings. | 4,22 | 0,85 | 4,41 | 0,71 | -2,963 | 0,004 | -0,172 |

| 2. I usually worry a lot about how I feel. | 3,95 | 0,86 | 4,11 | 0,78 | -3,753 | <0,001 | -0,138 |

| 3. I usually spend time thinking about my emotions. | 3,76 | 1,01 | 3,84 | 0,98 | 5,898 | <0,001 | -0,057 |

| 4. I think it is worth paying attention to my emotions and mood. | 4,38 | 0,81 | 4,35 | 0,81 | 0,347 | 0,729 | 0,026 |

| 5. I let my feelings affect my thoughts. | 3,46 | 1,05 | 3,38 | 0,96 | 1 | 0,319 | 0,056 |

| 6. I think about my mood constantly. | 2,9 | 1,11 | 2,9 | 1,01 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 7. I often think about my feelings. | 3,56 | 0,93 | 3,59 | 0,93 | -0,358 | 0,721 | -0,023 |

| 8. I pay close attention to how I feel. | 3,52 | 0,92 | 3,7 | 0,96 | -2,242 | 0,026 | -0,135 |

| 9. I am sure about my feelings. | 3,24 | 1,08 | 3,43 | 1,06 | -2,441 | 0,016 | -0,126 |

| 10. I can often define my feelings. | 3,31 | 1,03 | 3,48 | 1,01 | -2,559 | 0,011 | -0,118 |

| 11. I almost always know how I feel. | 3,21 | 0,99 | 3,46 | 0,96 | -3,398 | <0,001 | -0,181 |

| 12. I usually know my feelings about people. | 3,72 | 0,85 | 3,91 | 0,89 | -2,54 | 0,012 | -0,154 |

| 13. I am often aware of my feelings in different situations. | 3,8 | 0,83 | 3,92 | 0,77 | -1,814 | 0,072 | -0,106 |

| 14. I can always tell how I feel. | 2,91 | 1,08 | 3,08 | 0,98 | -2,149 | 0,033 | -0,117 |

| 15. Sometimes I can tell what my emotions are. | 3,64 | 0,87 | 3,75 | 0,89 | -1,466 | 0,145 | -0,088 |

| 16. I can come to understand my feelings. | 3,73 | 0,92 | 3,86 | 0,88 | -1,665 | 0,098 | -0,102 |

| 17. Although I sometimes feel sad, I usually have an optimistic outlook. | 3,34 | 1,15 | 3,59 | 1,09 | -3,181 | <0,001 | -0,158 |

| 18. Although I feel bad, I try to think of pleasant things. | 3,18 | 1,05 | 3,49 | 0,99 | -4,417 | <0,001 | -0,215 |

| 19. When I am sad, I think of all the pleasures of life. | 2,67 | 1,08 | 2,95 | 1,13 | -3,463 | <0,001 | -0,179 |

| 20. I try to think positive thoughts even when I feel bad. | 3,13 | 1 | 3,5 | 1,02 | -5,413 | <0,001 | -0,259 |

| 21. If I go over things too much, complicating them, I try to calm down. | 3,34 | 1,08 | 3,56 | 1,01 | -2,295 | 0,023 | -0,149 |

| 22. I try to be in a good mood. | 3,81 | 0,79 | 4,03 | 0,72 | -3,457 | <0,001 | -0,206 |

| 23. I have a lot of energy when I feel happy. | 4,56 | 0,62 | 4,55 | 0,62 | 0,126 | 0,9 | 0,011 |

| 24. When I am angry I try to get over it. | 3,78 | 0,92 | 3,86 | 0,9 | -1,282 | 0,202 | -0,062 |

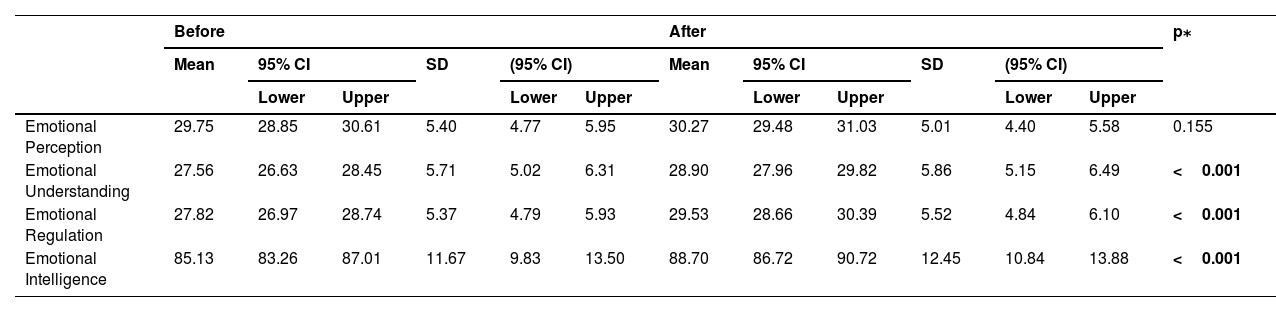

Table 3 shows the main hypothesis of our study since an increase in total EI and its factors is observed after the clinical practices (p<0.001).

TMMS-24 results and their factors before and after clinical practices.

| Before | After | p⁎ | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 95% CI | SD | (95% CI) | Mean | 95% CI | SD | (95% CI) | ||||||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Emotional Perception | 29.75 | 28.85 | 30.61 | 5.40 | 4.77 | 5.95 | 30.27 | 29.48 | 31.03 | 5.01 | 4.40 | 5.58 | 0.155 |

| Emotional Understanding | 27.56 | 26.63 | 28.45 | 5.71 | 5.02 | 6.31 | 28.90 | 27.96 | 29.82 | 5.86 | 5.15 | 6.49 | <0.001 |

| Emotional Regulation | 27.82 | 26.97 | 28.74 | 5.37 | 4.79 | 5.93 | 29.53 | 28.66 | 30.39 | 5.52 | 4.84 | 6.10 | <0.001 |

| Emotional Intelligence | 85.13 | 83.26 | 87.01 | 11.67 | 9.83 | 13.50 | 88.70 | 86.72 | 90.72 | 12.45 | 10.84 | 13.88 | <0.001 |

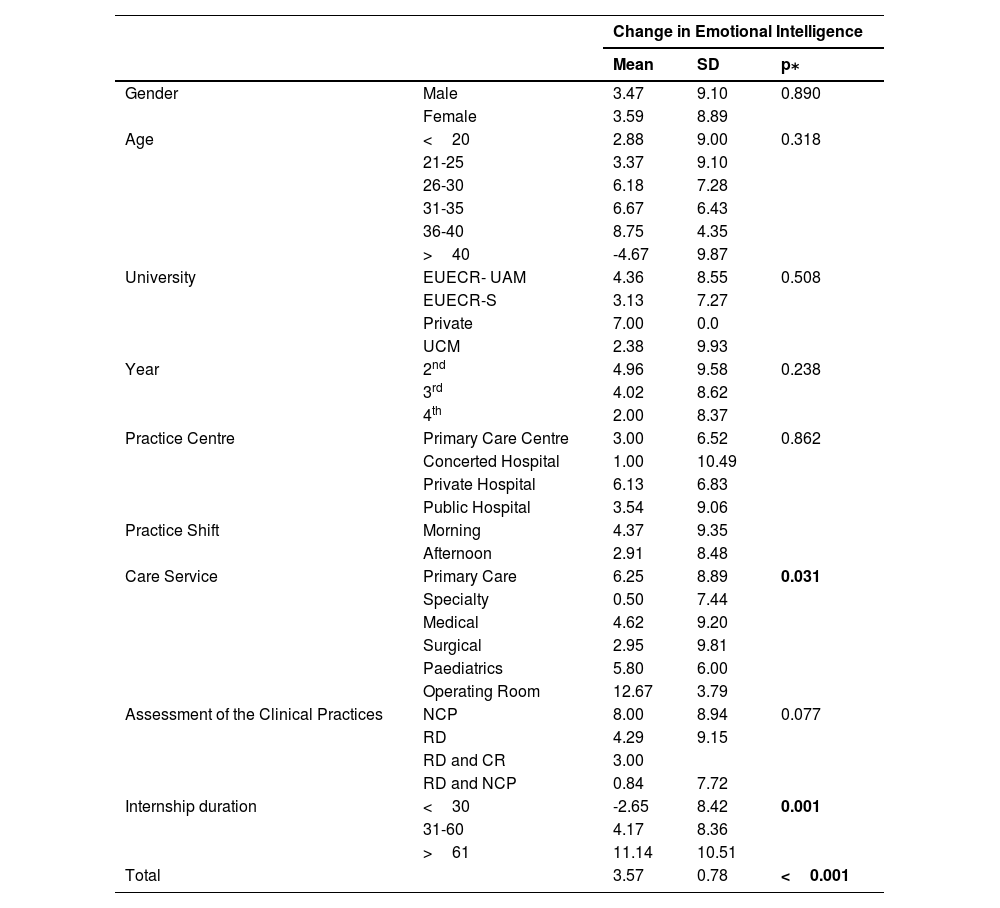

In the analysis according to the sociodemographic and academic characteristics carried out in Table 4, a statistically significant change (p=0.031) is observed in EI according to the type of service in which they carry out the practices, the main hypothesis of this paper, highlighting the Operating Room as the unit in which the greatest change occurs (12.67±3.79) when compared to the special care units, where it is lower (0.50±7.44). Likewise, differences are also observed according to duration of the clinical practices, increasing when the periods of practices are longer. This relationship is also observed in the change in EI dimensions such as emotional perception (p=0.001), emotional understanding (p=0.008) and emotional regulation (p=0.004).

Change in ei and its dimensions according to sociodemographic and academic variables.

| Change in Emotional Intelligence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | p⁎ | ||

| Gender | Male | 3.47 | 9.10 | 0.890 |

| Female | 3.59 | 8.89 | ||

| Age | <20 | 2.88 | 9.00 | 0.318 |

| 21-25 | 3.37 | 9.10 | ||

| 26-30 | 6.18 | 7.28 | ||

| 31-35 | 6.67 | 6.43 | ||

| 36-40 | 8.75 | 4.35 | ||

| >40 | -4.67 | 9.87 | ||

| University | EUECR- UAM | 4.36 | 8.55 | 0.508 |

| EUECR-S | 3.13 | 7.27 | ||

| Private | 7.00 | 0.0 | ||

| UCM | 2.38 | 9.93 | ||

| Year | 2nd | 4.96 | 9.58 | 0.238 |

| 3rd | 4.02 | 8.62 | ||

| 4th | 2.00 | 8.37 | ||

| Practice Centre | Primary Care Centre | 3.00 | 6.52 | 0.862 |

| Concerted Hospital | 1.00 | 10.49 | ||

| Private Hospital | 6.13 | 6.83 | ||

| Public Hospital | 3.54 | 9.06 | ||

| Practice Shift | Morning | 4.37 | 9.35 | |

| Afternoon | 2.91 | 8.48 | ||

| Care Service | Primary Care | 6.25 | 8.89 | 0.031 |

| Specialty | 0.50 | 7.44 | ||

| Medical | 4.62 | 9.20 | ||

| Surgical | 2.95 | 9.81 | ||

| Paediatrics | 5.80 | 6.00 | ||

| Operating Room | 12.67 | 3.79 | ||

| Assessment of the Clinical Practices | NCP | 8.00 | 8.94 | 0.077 |

| RD | 4.29 | 9.15 | ||

| RD and CR | 3.00 | |||

| RD and NCP | 0.84 | 7.72 | ||

| Internship duration | <30 | -2.65 | 8.42 | 0.001 |

| 31-60 | 4.17 | 8.36 | ||

| >61 | 11.14 | 10.51 | ||

| Total | 3.57 | 0.78 | <0.001 | |

EUECR- UAM: Red Cross Nursing School attached to Universidad Autónoma de Madrid.

EUECR-S: Red Cross Nursing School attached to Universidad de Sevilla.

UCM: Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

RD: reflective diaries.

NCP: nursing care processes.

KEZKAK: Stressors inherent to clinical practices.

S-NSPIC: Nursing students' perceptions about their instructor's caring behaviours.

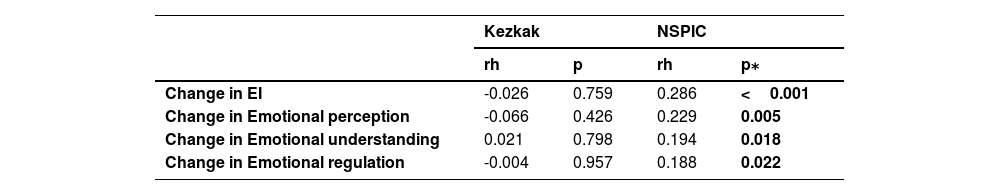

Table 5 shows the correlations between the change in EI and its factors with the score obtained in the KEZKAK and NSPIC questionnaires. An inversely proportional relationship is observed between stress and the change in EI and the emotional perception and emotional regulation factors, for which it could be asserted that the greater the stress, the less change in EI and its factors, although this relationship is not statistically significant. On the other hand, a weak but statistically significant direct relationship (rh<0.3) is observed between the change in EI and all its factors with respect to the relationship with the tutors, so that the better the relationship with the tutors, the greater the change in EI and its factors.

Correlations between the change in ei and its factors with the score obtained in the kezkak and nspic questionnaires.

| Kezkak | NSPIC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rh | p | rh | p⁎ | |

| Change in EI | -0.026 | 0.759 | 0.286 | <0.001 |

| Change in Emotional perception | -0.066 | 0.426 | 0.229 | 0.005 |

| Change in Emotional understanding | 0.021 | 0.798 | 0.194 | 0.018 |

| Change in Emotional regulation | -0.004 | 0.957 | 0.188 | 0.022 |

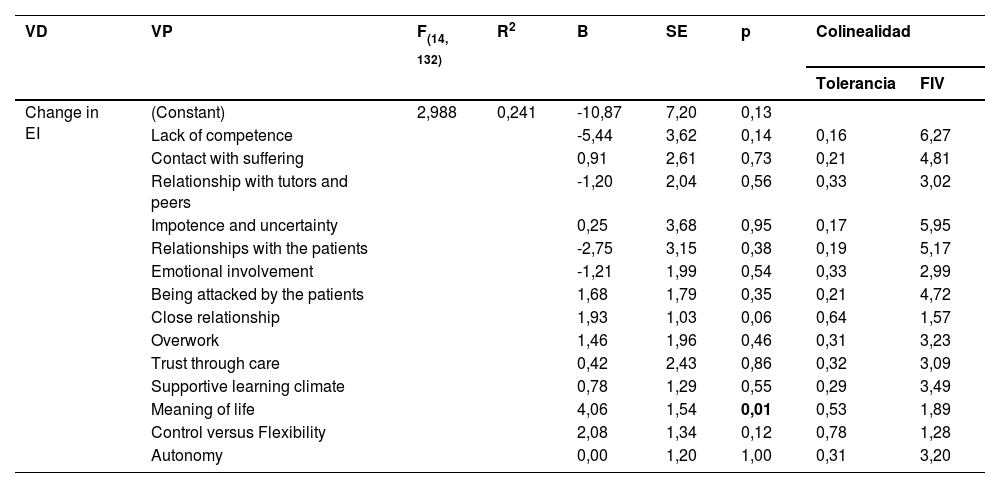

Finally, the multiple linear regression model with the forced entry method was studied to predict the change in the perception of EI based on the factors of perception of the instructor's care relationship and the stressors of previous clinical practices.

The best model evaluates the change in the perception of EI, the dimensions introduced would explain 24.1% (corrected R2=16%) of the variance of the perception of EI, this change being statistically significant (p=0.001). It is interesting to observe the coefficients shown in Table 6.

Multiple linear regression on the change in the perception of EI.

| VD | VP | F(14, 132) | R2 | B | SE | p | Colinealidad | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tolerancia | FIV | |||||||

| Change in EI | (Constant) | 2,988 | 0,241 | -10,87 | 7,20 | 0,13 | ||

| Lack of competence | -5,44 | 3,62 | 0,14 | 0,16 | 6,27 | |||

| Contact with suffering | 0,91 | 2,61 | 0,73 | 0,21 | 4,81 | |||

| Relationship with tutors and peers | -1,20 | 2,04 | 0,56 | 0,33 | 3,02 | |||

| Impotence and uncertainty | 0,25 | 3,68 | 0,95 | 0,17 | 5,95 | |||

| Relationships with the patients | -2,75 | 3,15 | 0,38 | 0,19 | 5,17 | |||

| Emotional involvement | -1,21 | 1,99 | 0,54 | 0,33 | 2,99 | |||

| Being attacked by the patients | 1,68 | 1,79 | 0,35 | 0,21 | 4,72 | |||

| Close relationship | 1,93 | 1,03 | 0,06 | 0,64 | 1,57 | |||

| Overwork | 1,46 | 1,96 | 0,46 | 0,31 | 3,23 | |||

| Trust through care | 0,42 | 2,43 | 0,86 | 0,32 | 3,09 | |||

| Supportive learning climate | 0,78 | 1,29 | 0,55 | 0,29 | 3,49 | |||

| Meaning of life | 4,06 | 1,54 | 0,01 | 0,53 | 1,89 | |||

| Control versus Flexibility | 2,08 | 1,34 | 0,12 | 0,78 | 1,28 | |||

| Autonomy | 0,00 | 1,20 | 1,00 | 0,31 | 3,20 | |||

There are countless studies on the best strategies to increase EI and its association with other variables, but the impact of the clinical environment on Nursing students has rarely been longitudinally analysed, as it has been studied in other professions.20 In addition, this paper is a pioneer in its field by contemplating and relating EI with other variables of interest such as stressors of the clinical practices and the relationships with the tutors. Our findings refute the results obtained in the studies by Lewis21 and by Larin et al.22 carried out on Physiotherapy and Nursing students, respectively, without finding significant changes in EI, although they used models other than the one proposed by Salovey and Mayer. This study also shows that clinical settings play an important role in this change because, although the change may be due to the natural emotional maturation that occurs over time or personal life events external to the practices,23 it has been produced unevenly according to the clinical unit, which should reassure clinical tutors and university professors, as it validates the fundamental role that clinical environments play in the acquisition of both practical and emotional skills, as also occurs with other disciplines.20

This study evidences the unequal impact that clinical services exert on students' IE. The EI perception values obtained initially are adequate, as is usual in Nursing students24,25 ensuring that they can display enhanced empathetic behaviours, deal with complex emotional scenarios, develop appropriate team interactions, and make better clinical decisions. However, it is shown that special clinical services hinder the acquisition of emotional skills and even promote their loss, as is also the case with Nursing professionals, as indicated by the study on nurses from the emergency service of a third-level hospital in Galicia, where they obtained adequate mean EI values but lower than those of our students, possibly related to the medium-high levels of burnout and job instability26 and by the study carried out with nurses from an Intensive Care Unit of a tertiary-level care hospital in Catalonia that obtained similar results: adequate values for emotional understanding and emotional regulation but decreased in emotional perception, where all medians of perceived EI are also lower than ours 27. Therefore, greater attention should be paid to the students who attend these units and analyse whether their tutors are in a suitable situation to favour EI development and, if not, provide solutions and further training in emotional coping skills.

Another determining criteria for the improvement of EI obtained in this study is the duration of the clinical practices; it has been shown that short turnovers (<30 days) generate maintenance, and even loss, of EI and its factors when compared to longer periods. Therefore, according to the results obtained, universities should be recommended to carry out longer turnovers because this favours the acquisition of emotional skills.

In our study, we have not been able to demonstrate the negative influence exerted by the stressors of clinical practices on EI acquisition, although this relationship between stress and EI has been shown by other authors, and may exert a negative influence on EI skills, especially if the students are poorly supervised.27,28 What is irrefutable is that the students report high stress levels both in this and in other research studies;9 therefore, universities must work to achieve empathic and compassionate learning environments.29

Finally, the influence of the instructor's care on the improvement of EI has been demonstrated. A previous study in the field of occupational therapy30 supports our result and concludes that those who show inadequate communication skills, disinterest, great control or a closed mindset can decrease the students' clinical and emotional performance. The experience with instructors also influences career interest and job motivation.31 This information should be passed on to the tutors so that they are aware that a poor supervision environment can affect the students' future abilities32 and, therefore, for them to be properly involved in the teaching-learning process.

Among the strengths of this study we find the type of research carried out: a longitudinal study which allows evaluating the change in EI, and that is also carried out in the students' clinical practices, a moment that has been analysed on few occasions. In addition, it is conducted in different universities, which entails greater external validity. Finally, it includes variables of special interest such as the stressors of clinical practices and the perception regarding the instructor's care, which have been little studied in our country. However, we also found some limitations that must be taken into account, such as the scarce sociodemographic information collected, which was limited by some ethics committees to prevent identification of the students; the sample selection which, although it complies with the calculated size, has not been chosen randomly, which could hinder extrapolating the results; and finally, the insufficient representation of some age groups or the feminization of the sample may underestimate or overestimate the results obtained, although they are intrinsic characteristics to our profession and moment of study.

ConclusionsThe results of this study conclude that exposure to clinical practices influences the development of emotional skills in Nursing students. Acquisition of EI depends on the clinical service in which the students carry out their internships, their duration and the relationships they develop with the tutors. These criteria must be taken into account for the creation of study plans that favour both the increase in knowledge and social and emotional skills, guaranteeing the students' incorporation into the labour market with all possible tools. In Spain, their duration is chosen by the universities themselves since Order CIN/2134/2008 of July 3rd, which establishes the requirements for the verification of official university degrees that enable practicing the Nursing profession, only indicates that the Supervised Practices and the Final Degree Project must include 90 ECTS Credits4 so it would be an easily modifiable criterion. Future lines of research should investigate the factors that affect the relationship between instructors and students and the stressors of clinical practices that influence the development of skills, as well as analyse the impact of specific programs for the development of emotional skills both in students and in professionals.