Nomophobia, an emerging psychological phenomenon that represents anxiety when there is no access to a mobile phone, has a prevalence ranging from 6% to 73% in global studies and is associated with physical and mental health problems. This study aims to validate and expand the assessment of the Nomophobia Questionnaire (NMP-Q) through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and network analysis among medical students in Peru.

MethodsAn observational cross-sectional study was conducted with 3139 medical students from 38 schools in Peru, using the Spanish-adapted NMP-Q. Data were collected through an online survey, promoted via social media and direct contacts. Factorial and network analyses were performed to evaluate the internal structure and dynamics of the questionnaire.

ResultsCFA showed an excellent fit for the 4-factor model of the NMP-Q, with factor loadings above 0.700 and high fit indices (CFI=0.996, RMSEA=0.031, SRMR=0.041). The reliability of the factors was high (McDonald's omega: 0.87–0.95). Network analysis revealed significant interactions among the items, identifying the most influential nodes, with “Loss of connection” and “Inability to communicate” being the most prominent in terms of centrality. The network showed adequate precision and stability, with stability coefficients above 0.75 for most indices.

ConclusionThe NMP-Q proved to be a valid and reliable tool for assessing nomophobia among medical students in Peru.

La nomofobia, un fenómeno psicológico emergente que representa la ansiedad al no tener acceso al teléfono móvil, tiene una prevalencia que oscila entre el 6% y el 73% en estudios a nivel mundial y está asociada a problemas de salud física y mental. Este estudio busca validar y ampliar la evaluación del Cuestionario de Nomofobia (NMP-Q) mediante análisis factorial confirmatorio y de red en estudiantes de medicina en Perú.

MétodosSe realizó un estudio observacional y transversal con 3139 estudiantes de medicina de 38 escuelas en Perú, utilizando el NMP-Q adaptado al español. Los datos se recolectaron a través de una encuesta en línea, promovida mediante redes sociales y contactos directos. Se llevaron a cabo análisis factoriales y de red para evaluar la estructura interna y la dinámica del cuestionario.

ResultadosEl análisis factorial confirmatorio (CFA) mostró un excelente ajuste del modelo de cuatro factores del NMP-Q, con cargas factoriales superiores a 0.700 y altos índices de ajuste (CFI = 0.996, RMSEA = 0.031, SRMR = 0.041). La fiabilidad de los factores fue alta (omega de McDonald: 0.87 a 0.95). El análisis de red reveló interacciones significativas entre los ítems, identificando los nodos más influyentes, siendo “Pérdida de conexión” e “incapacidad para comunicarse” como los más destacados en términos de centralidad. La red mostró precisión y estabilidad adecuadas, con coeficientes de estabilidad superiores a 0.75 para la mayoría de los índices.

ConclusiónEl NMP-Q demostró ser una herramienta válida y confiable para evaluar la nomofobia en estudiantes de medicina en Perú.

The modern era has witnessed the rise of “nomophobia,” an emerging psychological phenomenon triggered by excessive mobile phone use.1 This term, an acronym for “no mobile phone phobia”,2 describes the anxiety or distress experienced when one does not have access to a mobile device.3 A systematic review by León-Mejía et al. revealed that the prevalence of nomophobia ranged between 6% and 73% in studies conducted worldwide.4 Rodríguez-García et al., in a literature review, found that nomophobia is associated with various negative consequences, including impacts on personality, self-esteem, anxiety, stress, academic performance, and other physical and mental health issues.5 Due to these concerns, several instruments have been developed to assess nomophobia or related constructs.6,7

Among these, the Nomophobia Questionnaire (NMP-Q) is the most widely used validated scale.5,8 This instrument, developed by Yildirim and Correia, assesses the severity of nomophobia.9 It is a self-report questionnaire consisting of 20 statements divided into 4 dimensions.9 Previous studies using the NMP-Q have confirmed its internal consistency (with Cronbach's alpha ranging from 0.80 to 0.94), representing very good to excellent psychometric properties.8

However, most studies analyzing the internal structure of the NMP-Q have relied on traditional techniques, such as confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), to validate its dimensionality.10–13 While useful, CFA assumes that items within each factor are independent once latent factors are accounted for,14 potentially oversimplifying the complex interaction of nomophobia symptoms.15,16 In contrast, network analysis allows for visualizing the items as an interconnected system, providing a more dynamic representation of how symptoms interact and contribute to the phenomenon of nomophobia.17

In light of this gap, this study aims to validate and expand the analysis of the NMP-Q by conducting a CFA followed by a network analysis, with the goal of exploring the internal dynamics of the questionnaire in greater depth. Network analysis will allow for a more detailed exploration of how items interrelate and contribute to the overall structure of the questionnaire, overcoming the limitations of previous studies. This holistic approach is crucial for a correct interpretation of the results and for identifying the most influential nodes within the questionnaire, as well as the most significant interactions between the dimensions of the NMP-Q.

Materials and methodsDesign, context, and participantsA cross-sectional observational study was conducted with the aim of validating the NMP-Q in Peru, using data obtained from a previous investigation.18 Medical students over the age of 18, enrolled in human medicine faculties at 38 of the 45 Peruvian universities offering this program, were selected to participate voluntarily. Individuals who had not used a mobile phone in the month prior to the survey were excluded. A convenience sampling method was used to select participants.

Instruments and variablesNomophobia Questionnaire (NMP-Q)The NMP-Q developed by Yildirim and Correia,9 adapted and validated by Leon-Mejia for Spanish, was used.12 It is composed of 4 dimensions: lack of access to information (4 items), loss of comfort and wellbeing (5 items), inability to communicate (6 items), and loss of connection (5 items), making a total of 20 items. It is graded using a Likert-7 scale, where 1 means “strongly disagree” and 7 “strongly agree.” The final score can range from 20 to 140 points, which implies that the higher the score, the higher the severity of nomophobia. Previous studies have confirmed the 4-factor structure with an overall reliability of 0.964 using Cronbach's alpha, and have shown adequate goodness of fit indexes in higher university students from Peru.19

ProceduresAfter obtaining approval from the ethics committee, data collection was conducted in 2 stages between June 2020 and March 2021. The researchers created a Facebook page to publicize their work and invite medical students in Peru to participate. They then recruited 23 co-investigators from different medical schools, trained them to contact students from their respective universities via WhatsApp, and provided them with a link to an online survey hosted on Google Forms. As an incentive, participants who completed the survey were given access to a Google Drive folder containing open-access medical course materials. A non-probability sampling technique, known as convenience sampling, was therefore used.18

Data analysisSample size calculationTo estimate the required sample size for CFA and network analysis, 2 distinct methods were employed. For the CFA, Arfin's sample size calculator was used with the following parameters: an expected comparative fit index (CFI) of 0.95, 20 items, 4 factors, an average factor loading of 0.6, a total factor correlation of 0.3, and a statistical power of 0.80. This indicated a minimum of 316 observations needed. The sample size for the network analysis was determined using the “powerly” package with 20 nodes, a statistical power of 0.80, and a density of 0.40, resulting in a minimum of 1000 observations required.20

Internal structure validity and relationship with other variablesThe analysis was conducted in two stages: first with CFA and then with a network approach. To evaluate the validity of the internal structure, a CFA was performed using the weighted least square mean and variance adjusted estimator due to the ordinal nature of the ítems.21 The fit indices used were the CFI, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), considering good fit with values of CFI>0.90,22 RMSEA<0.100, and SRMR<0.080.23 Reliability was assessed with McDonald's omega coefficient.24 All analyses were conducted in RStudio using the lavaan package.25

Network analysisThe analyses were performed in RStudio, adhering to reporting standards for psychological network analysis.26 A 3-step approach was followed: (1) network estimation, (2) stability and accuracy estimation, and (3) comparative analysis. The packages used included powerly,20 qgraph,27 bootnet,28 and networkcomparisontest.29

The bootnet package estimated an unregularized partial network using the ggmModSelect estimator and a Spearman correlation matrix.30 Node centrality was calculated using strength due to the presence of only positive edges.31 Closeness and betweenness were not estimated due to their unsuitability for interpreting psychological variables.32

To assess the network's stability and accuracy, a non-parametric case-dropping bootstrap technique based on 1000 cases was used. The stability coefficient (SC) was employed, which indicates the number of cases that can be dropped while maintaining a correlation of at least 0.70 with a 95% probability. Ideally, the SC should not be below 0.25 and is preferably above 0.5.33 Accuracy was assessed by creating a 95% bootstrap confidence interval for the resampled edges.28

Finally, the ‘NetworkComparisonTest’ library was used to compare 2 networks (X and Y) using a 2-tailed permutation test to determine significant differences between the groups. In this test, individuals were randomly assigned to each group 1000 times, and discrepancies between groups were calculated in each iteration, with the aim of testing the null hypothesis that both groups are identical.

ResultsCharacteristics of the study populationDuring the study period, 3139 medical students from 38 medical schools in 18 cities across Peru were surveyed. The median number of students per school was 23, ranging from 1 to 308. The median age of the participants was 22 years, with 61.1% identifying as female. A majority (74.6%) were financially dependent on their parents, 23.8% attended universities in Lima, and 48.7% were in the fourth to sixth years of their medical training. In terms of mobile phone usage, 76.1% of students had mobile internet data plans, and 26.7% used their phones for less than 4 h a day. WhatsApp was the most commonly used social network, favored by 65.8% of the respondents (Table 1).

Characteristics of surveyed students (n=3139).

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 1220 (38.9) |

| Female | 1919 (61.1) |

| Agea | 22 (20–24) |

| How you support your daily expenses | |

| Work | 174 (5.6) |

| Receives money from relatives | 2343 (74.6) |

| Works and receives money from relatives | 622 (19.8) |

| City where your university is located (categorized by participants): | |

| Lima | 746 (23.8) |

| Arequipa, Trujillo, Chiclayo | 615 (19.6) |

| Piura, Huancayo, Cusco | 813 (25.9) |

| Other | 965 (30.7) |

| Year of study | |

| 1st–3rd | 1609 (51.3) |

| 4th–6th | 1530 (48.7) |

| Parents' use of information and communication technologies is defined as “advanced” or “expert”: | |

| Father | 621 (19.8) |

| Mother | 393 (12.5) |

| Years using a Smartphonea | 7 (6–9) |

| Has a mobile internet data plan | |

| Yes | 2388 (76.1) |

| No | 751 (23.9) |

| How much time of the day do you spend using your cell phone? | |

| Less than 4 h | 838 (26.7) |

| 4–5 h | 1269 (40.4) |

| 6–9 h | 758 (24.2) |

| 10 h or more | 274 (8.7) |

| The main reason for using your smartphone | |

| Communication (video call, SMS, email) | 893 (28.5) |

| Education | 876 (27.9) |

| Social networks | 858 (27.3) |

| Entertainment (gaming, video, music, Netflix) | 512 (16.3) |

| Most used social network | |

| 2066 (65.8) | |

| 617 (19.7) | |

| 324 (10.3) | |

| TikTok | 74 (2.4) |

| 57 (1.8) |

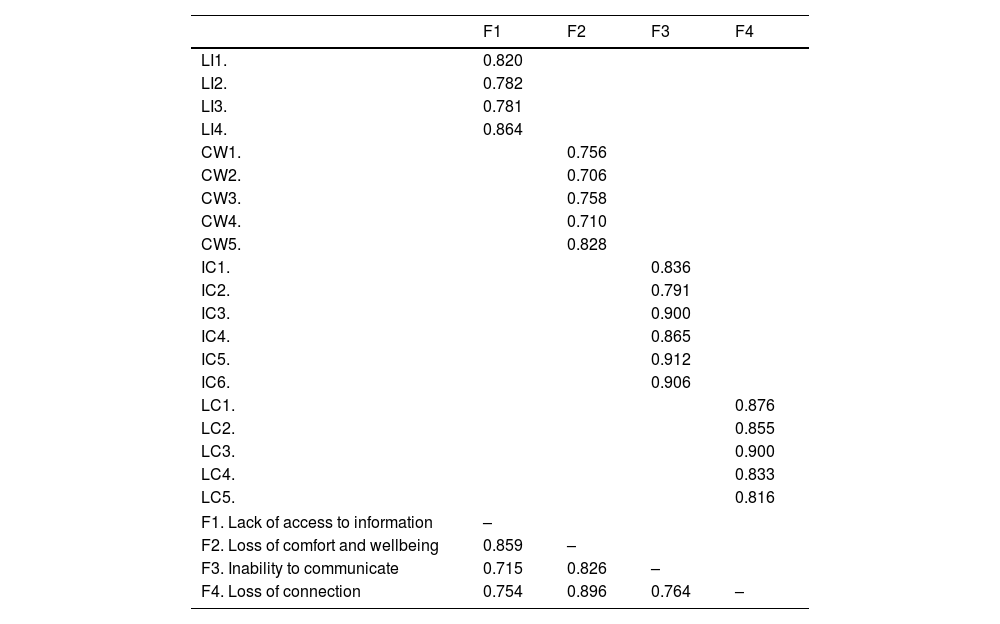

A 4-factor model from previous studies for CFA was used, as shown in Table 2. Factor loadings for all domains of the NMP-Q were higher than 0.700. The model fit indexes were CFI=0.996, RMSEA=0.031 (90% CI: 0.029–0.034), and SRMR=0.041. The reliability using McDonald's Omega of each factor was 0.89, 0.87, 0.95, and 0.93 for “lack of access to information,” “loss of comfort and wellbeing,” “inability to communicate,” and “loss of connection,” respectively.

Factor loading of the 4-factor model for the NMP-Q employing confirmatory factor analysis.

| F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LI1. | 0.820 | |||

| LI2. | 0.782 | |||

| LI3. | 0.781 | |||

| LI4. | 0.864 | |||

| CW1. | 0.756 | |||

| CW2. | 0.706 | |||

| CW3. | 0.758 | |||

| CW4. | 0.710 | |||

| CW5. | 0.828 | |||

| IC1. | 0.836 | |||

| IC2. | 0.791 | |||

| IC3. | 0.900 | |||

| IC4. | 0.865 | |||

| IC5. | 0.912 | |||

| IC6. | 0.906 | |||

| LC1. | 0.876 | |||

| LC2. | 0.855 | |||

| LC3. | 0.900 | |||

| LC4. | 0.833 | |||

| LC5. | 0.816 | |||

| F1. Lack of access to information | – | |||

| F2. Loss of comfort and wellbeing | 0.859 | – | ||

| F3. Inability to communicate | 0.715 | 0.826 | – | |

| F4. Loss of connection | 0.754 | 0.896 | 0.764 | – |

LI = lack of information; CW = comfort and wellbeing; IC = inability to communicate; LC = loss of connection.

After confirming the structure of the 4 dimensions of the NMP-Q through CFA, we conducted a network analysis, as shown in Fig. 1. Symptoms of each community are grouped close to each other, except for the ones related to “loss of comfort and wellbeing.” The total number of nodes was 20, with 81 out of 190 edges different from zero, and the mean weight of the edges was 0.05. In relation to centrality indexes, the node nomo18, corresponding to the “loss of connection” domain, had the highest expected influence, followed by nomo13, which corresponded to the “inability to communicate” domain.

Then, we assessed the network for its precision and stability, as shown in Fig. 2. To assess the precision of the network, we employed a non-parametric bootstrap with a 95% CI (Fig. 2a); this shows that for all 3 indexes, the sample mean falls within the bootstrapping mean, indicating adequate precision. Then, to assess stability, as cases are drooped (Fig. 2B), and the relationship between the original sample and the bootstrapped one remains similar in all three centrality indexes. This is clearer when analyzing the CS, which are 0.75 for Bridge expected influence, 0.75 for edges, 0.75 for expected influence, and 0.52 for strength. These coefficients are all superior to 0.25 (the minimum required). Hence, the network was of adequate precision and stability.

Regarding the bridge expected influence, which measures the nodes that connect different communities—in this case, dimensions, or factors, we found that node “nomo9,” which corresponds to “If I went a while without checking my smartphone, I'd feel the urge to check it,” was the most influential in terms of connection between groups.

DiscussionSummary of findingsWe conducted a CFA and network analysis on the NMP-Q in 3139 medical students from 38 medical schools in Peru between 2020 and 2021. Our main findings were as follows:

1) Internal structure validity:

The 4-factor model for NMP-Q demonstrated adequate goodness of fit and good reliability, providing strong evidence of internal structure validity. This confirms that the NMP-Q is a robust tool for measuring nomophobia.

2) Network analysis of dimensions:

The network analysis revealed that the nodes in dimension 2, “loss of comfort and wellbeing,” were dispersed. This indicates that these nodes were closely correlated with nodes from other dimensions, suggesting significant interrelation between emotional discomfort and other symptoms of nomophobia.

3) Most influential nodes within the network:

The network analysis identified the most influential nodes across different dimensions of the NMP-Q:

- •

Lack of access to information: The key node for this dimension was, “I would be irritated if I couldn't use my smartphone and its capabilities when I wanted to,” highlighting users' frustration when deprived of information access.

- •

Loss of comfort and wellbeing: The central node here was, “If I went for a while without being able to check my smartphone, I would wish I could look at it,” indicating a significant emotional response to the loss of habitual phone use.

- •

Inability to communicate: The strongest node across all dimensions was, “I would be anxious because I would not be able to keep in touch with my family and friends,” underscoring the critical role of smartphones in maintaining social communication.

- •

Loss of connection: For this dimension, the node “I would feel awkward because I would not be able to check my notifications of updates from my contacts and online networks” was most influential, pointing to the discomfort caused by a perceived disconnection from online networks.

These findings suggest that the most prominent symptoms of nomophobia are closely related to the users' need to maintain social connections through their smartphones.

4) Bridge expected influence:

The node with the highest bridge expected influence—indicating its significant influence across different dimensions—was, “If I went for a while without checking my smartphone, I would wish to look at it.” This finding suggests that this symptom may be the most severe or serve as the catalyst across the NMP-Q, as it influences all other dimensions the most.

Strengths and limitationsWhile our study presents several strengths, it is not without limitations that must be acknowledged when interpreting the results. First, data collection took place between 2020 and 2021, during the COVID-19 pandemic, a period when mobile phone usage increased significantly. This surge may have influenced the reported levels of nomophobia, and this temporal bias was not controlled for, which could have affected the outcomes.

Moreover, the data collection method, which involved online surveys with incentives, may have introduced sampling biases. This approach likely skewed the sample towards students who are more active on social media or who have greater access to technology, potentially excluding those with less internet or mobile device access. This is particularly relevant in the Peruvian context, where significant disparities in technology access exist between urban and rural areas, as well as across different socioeconomic levels. As a result, students who use mobile phones more frequently may be overrepresented, which could have influenced the reported levels of nomophobia. This bias should be considered when interpreting the study's findings.

Additionally, the study included students from various medical schools across Peru; however, a factorial invariance analysis among cultural subgroups was not performed. Given the notable cultural differences between Peru's coastal, highland, and jungle regions, this omission limits the generalizability of the results. Nevertheless, we tried to include all medical schools in Peru to ensure a broad representation of the student population. Future studies should address these regional and cultural variations to enhance the validity of the findings across diverse populations.

Finally, the NMP-Q was administered exclusively in an online format, which may have influenced participants' responses. The psychometric properties observed in this study cannot be generalized to in-person applications without further studies confirming their validity across different administration contexts. Furthermore, convergent and discriminant validity analyses were not included, limiting the ability to confirm that the questionnaire specifically measures nomophobia and not related constructs. Future research should incorporate convergent and discriminant validity analyses to better assess the questionnaire's specificity.

Comparison with other studiesThe NMP-Q exhibited an adequate fit with a 4-factor model, consistent with both the original study9 and international literature,8 although research within Latin America remains limited. This study validates the NMP-Q in the Peruvian context, thereby contributing to the literature on nomophobia in Latin America. Network analysis revealed a close clustering of symptoms within each community, except for those associated with the “loss of comfort and wellbeing” dimension, which displayed significant dispersion, indicating strong correlations with nodes from other dimensions. These findings extend beyond those reported by Li et al., the only previous study aimed at identifying the network structure of the NMP-Q,34 thus expanding the understanding of this structure.

Additionally, our study identified the most influential nodes within each dimension. For the “lack of access to information” dimension, the node “I would be annoyed if I could not use my smartphone and its capabilities when I wanted to” was the most influential. In the “loss of comfort and wellbeing” dimension, the node “If I went a while without checking my smartphone, I'd feel the urge to check it” emerged as the most influential, significantly interacting with the other dimensions of the NMP-Q. This finding aligns with Li et al.,34 who, despite this item not fully fitting the Rasch model, recommended its retention due to its psychometric importance, where the properties of the NMP-Q with and without this item were similar.35 Conversely, Li et al. identified a different node, “being worried that my family and/or friends could not reach me,” as the most influential, highlighting potential cultural differences in smartphone perception and usage.34 The constant need to check one's smartphone underscores an emotional and social dependency, suggesting that managing this dependency could be crucial to effectively addressing nomophobia.

For the “inability to communicate” dimension, the node “I would be anxious because I could not keep in touch with my family and friends” demonstrated the greatest strength among all nodes, consistent with findings by Li et al., who also reported this node as having the highest strength centrality. In the “loss of connection” dimension, the node “I would feel uncomfortable because I could not check my notifications for updates from my contacts and online networks” was the most significant, similar to the study by Li et al., which also showed high centrality. These findings underscore the critical importance of social connections maintained through smartphone use. Evidence suggests that smartphones help manage social anxiety and emotional regulation, particularly for individuals with nomophobia and low self-esteem.36

ImplicationsThis study confirms that the NMP-Q is a valid and reliable tool for assessing nomophobia among Peruvian medical students. Its application in educational settings can help identify levels of technology dependence, facilitating targeted interventions within medical faculties.

Since nomophobia can impact wellbeing and academic performance, the use of the NMP-Q may allow educators and health professionals to identify students at risk and provide them with appropriate support. This could include educational programs on healthy technology use and strategies to mitigate the psychological impact of excessive smartphone use.

Moreover, this instrument can be used to conduct comparisons across different educational institutions or regions within Peru, enabling an evaluation of how nomophobia varies in different contexts. These comparisons could prove useful in tailoring interventions to the specific characteristics of each studied group.

ConclusionsThis study provides robust evidence of the internal structure validity and the relationship with other variables of the NMP-Q among medical students in Peru. The validation of the NMP-Q in this specific context not only expands the applicability of the tool but also enriches the literature on nomophobia in Latin America.

Ethical responsibilitiesThis research was approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health Sciences at the Universidad Privada de Tacna (verification code: 042-FACSA-UI) and adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki on human research. Participation was voluntary, and all participants provided informed consent beforehand. All data collected were kept strictly confidential by the authors, and the study was conducted in full compliance with the ethical principles of autonomy, beneficence, and justice. The incentive offered to participants—a link to open-access medical course materials—was minimal and unlikely to unduly influence their decision to participate, ensuring adherence to ethical guidelines regarding voluntary participation without coercion.

FundingThe Universidad San Ignacio de Loyola financed the article processing charge (Code: USIL-2024). Funding acquisition was by author C.C. The funders had no role in study desing, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.