Nowadays, employees’ readiness for change plays a key role to implement many organizational change initiatives.

Using a sample of 510 bank employees in Jordan, this study seeks to analyze how high-performance human resource management practices and affective commitment impact employees’ readiness for change. We also seek to study the role of readiness for change in improving employee performance.

The results obtained through statistical analysis demonstrate a positive association between some high-performance human resource management practices with both affective commitment and readiness for change. Results also show a positive relationship between affective commitment and readiness for change.

We have also found that readiness for change is positively related to employees’ individual performance. Finally, our findings show that hierarchy culture positively moderates the relation of high-performance human resource management practices with affective commitment.

Organizational change has become a core activity to sustain the efficiency of organizations and increase their ability to respond and adapt to the environment and to the competitive marketplace which imposes changes (Mabey, Salaman & Storey, 1998). By using a variety of HRM practices to provide organizations with human resource who possesses the required knowledge, skills, abilities, and behavioural trends to accomplish change strategies, the human resource management (HRM) function can play a central role in enhancing organizational change (Ullah, 2012).

Employees readiness for change “reflects the extent of the cognitive and emotional tendency of individuals to accept and adopt a specific plan to purposefully change the status quo and move forward ”(Wang, Olivier & Chen, 2020, p. 20) . As individuals play an essential role in the change process, readiness for change is considered a key construct to implement many change initiatives (Rusly, Corner & Sun, 2012).

Nevertheless, researchers have pointed out that many important topics related to antecedents and consequences of readiness for change have not been previously studied. In organizational change research, the focus has often been at the organizational level in a macro-level focus on systems (Judge, Thoresen, Pucik & Welbourne, 1999). Some researchers also adopted a micro-level perspective on change, focusing more on the role of individuals in implementing changes. Nevertheless this aspect still needs further research and exploration, due to the importance of the central role that individuals play in the success of change initiatives. Only some antecedents (such as policies supporting change, trust in peers and leaders or participation at work) and very few consequences (e.g., perceived benefits of the change process) have been previously analysed in deep (Choi, 2011; Drzensky, Egold & van Dick, 2012).

In addition, there is a need of examining the role of moderating variables in the context of readiness for change besides its antecedents and consequences. Particularly, the influence of organizational culture types on individuals' readiness to change could vary depending on the country where the study is conducted, due to differences in national cultural characteristics for each country (Hofstede, Hofstede & Minkov ,2010). It is interesting to examine the moderating role of organizational culture in countries like Jordan, where human resource management applications are still in the beginnings.

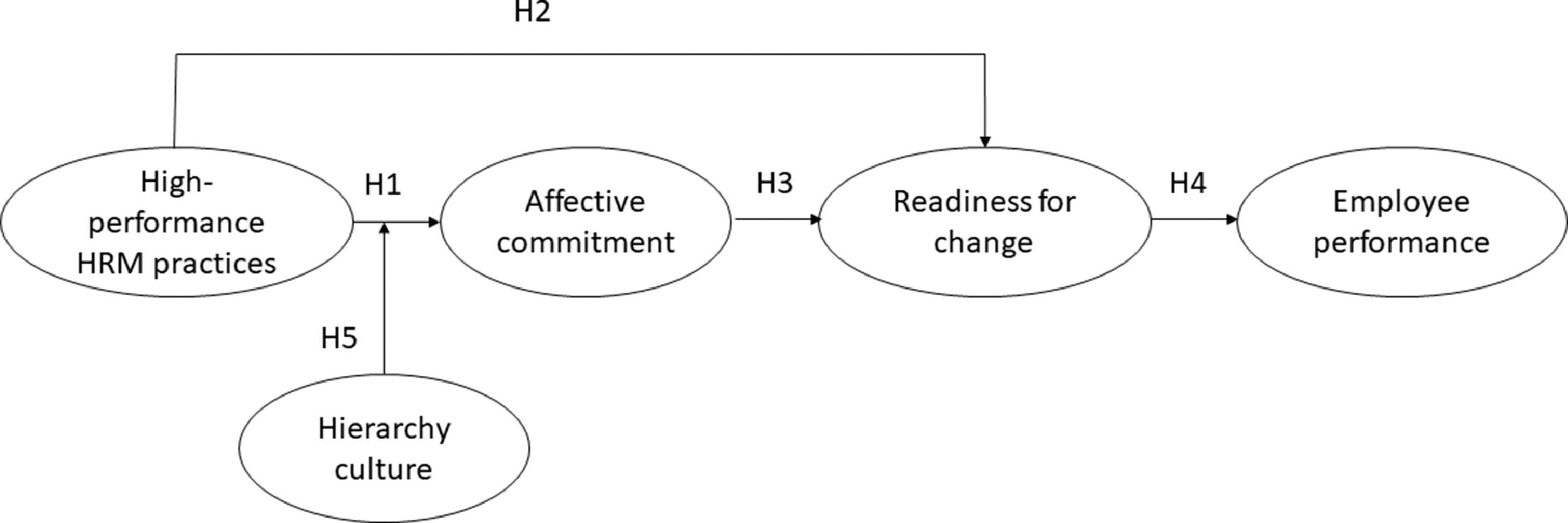

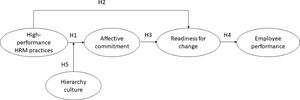

The present study examines the relevance of two potential antecedents of employees’ readiness for change, affective commitment and high-performance human resource management practices (HPHRMP), using a sample of bank employees in Jordan. As organizational change is intended to contribute to organizations success (Eliyana, Ma'arif & Muzakki, 2019), a performance construct, employees’ performance, is considered as a final result of the proposed model. Finally, hierarchy organizational culture is considered a moderator of the relationship between HPHRMP and affective commitment.

Consequently, the main research questions considered in this study are the following:

- -

Do HPHRMP and affective commitment produce employees’ readiness for change? What HPHRMP are more relevant for promoting readiness for change?

- -

Is employees’ readiness for change related to employee's performance?

- -

Does hierarchy culture influence the relationship between HPHRMP and affective commitment?

By answering these questions, the present work aims to contribute to prior literature by adding light on antecedents and consequences of employees’ readiness for change.

Focusing on HPHRMP and employees’ readiness for change, this study unveils the human factors that can make employees actively participate in organizational change.

Despite organizational change management and HRM literature highlight that one of the critical reasons for the failure of change initiatives is the neglect of the human element (Szamosi & Duxbury, 2002), researchers' interest in studying readiness for change, and particularly, the relationship between HRM practices and readiness for change is relatively recent.

Some researchers have noted that different HRM policies and practices can support readiness for change, also helping to promote high-performance and commitment toward change process (Maheshwari & Vohra, 2015). Particularly, prior research has highlighted the potential role of HPHRMP to produce organizational change (Tummers, Kruyen, Vijverberg & Voesenek, 2013). Nevertheless, existing research do not provide in-depth analysis on how HPHRMP enhances organizational change (Francis, 2003) and, particularly, readiness for change.

Very few studies have examined the relationship between employee commitment and readiness for change (e.g., Kwahk & Kim, 2008). Some of them consider organizational commitment as a global construct, without considering different commitment types. As the affective, continuance, and normative types of commitment have a different nature, their effect on readiness for change could be different. Prior research underlines that employees who have a strong affective commitment believe in the change and desire to contribute to its success (e.g. Meyer, Srinivas, Lal & Topolnytsky, 2007). However, the role of affective commitment to enhance readiness for change have not been studied in deep, which increases the novelty of the proposed research model.

Little research has examined consequences of readiness for change different from those related to change constructs (Alqudah, n.d.). The analysis of the relationship between readiness for change and employees’ performance contributes to prior literature by considering a non-studied relevant outcome for business success. As improving the performance of workforce is a common goal for HR managers, it is interesting to find out if, besides promoting organizational change, readiness for change positively influence employees’ performance. If so, enhancing employees’ readiness for change should be a key target for organizations, as could contribute to business success by both enhancing change and, employees’ performance as well.

Finally, the analysis of the role of the moderating role of hierarchical culture in the relationship between HPHRMP and affective commitment contributes to clarify the role of organizational culture in the proposed relationship and, particularly, in a non-studied country. Banking industry has traditionally been dominated by companies characterized as clan and hierarchy-type organizations, existing multiple hierarchical levels, tightly integrated, highly regulated and controlled, and, finally, an old-boy network (Cameron & Quinn, 2011a). Jordanian banks are not an exception, since the hierarchy culture is dominant within many banks in Jordan (Al-Abdullat & Dababneh, 2018). Examining the role of hierarchy culture will help bank managers interested in improving HRM and promote readiness for change to decide about keeping or changing the dominant culture.

2Theoretical framework and hypotheses development2.1Theoretical frameworkThe analysis of antecedents and consequences of employees’ readiness for change can be developed under the umbrella of different theories. This study mainly draws on Social exchange theory (SET) and The Ability, Motivation and Opportunity (AMO) foundations to develop the proposed relationships.

Social exchange theory, SET, (Blau, 1964) provides a theoretical framework to link HRM practices to affective commitment and employees readiness for change. SET assumes that discretionary benefits from an exchange partner will be returned back by the other party in a discretionary way in the longer term (Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002), holding the notion that individuals seek favourable outcomes relative to their inputs (Cook, Molm & Yamagishi, 1993). Thus, in a relationship like the employment relationship, SET implies that individuals become bound to return benefits or services to their partners in the exchange (Blau, 1964).

When employees understand HRM practices as expressing investment, appreciation, and recognition, they will start to perceive themselves in a social exchange, rather than a purely mercantile relationship (Shore & Shore, 1995). Employees who receive the organizations' long-term investment through HRM practices feel obligated to repay (Gong, Chang & Cheung, 2010).

The Ability, Motivation and Opportunity (AMO) model (Appelbaum, Bailey, Berg, Kalleberg & Bailey, 2000) is useful to explain the relationship between readiness for change and employees’ individual performance. AMO framework propose that to ensure the employee's discretionary effort, three elements must be in place: 1) employees must have the necessary skills, 2) they need the appropriate motivation, and 3) employers must offer them the opportunity to participate (Appelbaum et al., 2000).

Abilities refer to knowledge and skills that employees possess. Bos-Nehles, Van Riemsdijk & Kees Looise, 2013 stress the importance of the ability dimension claiming that without ability neither motivation nor opportunity will add much to performance, even though both dimensions are extremely important. Ability-enhancing practices intend to buy skills and/or enhance the existing employees' skills (Ma Prieto & Pérez-Santana, 2014).

Motivation deals with employees' willingness to perform, which can be reinforced by two types of motivation: extrinsic or intrinsic motivation (Marin-Garcia & Tomas, 2016). The opportunity to perform refers to the work structure and environment that provide the employees with the necessary support and avenues for expression (Armstrong & Brown, 2019). Providing employees with opportunities often leads to an increase in their confidence because they use greater autonomy in performing their tasks (Jiang, Lepak, Hu & Baer, 2012; Obeidat, Mitchell & Bray, 2016).

The AMO framework provides the basis for understanding the strategic value of HPHRMP. HPHRMP can be conceptualized along the three dimensions of the model: ability-enhancing practices, motivation-enhancing practices, and opportunity-enhancing practices (Obeidat et al., 2016). Employing an appropriate combination of different HPHRMP rather than individual practices ensures the enhancement of all three components of the AMO model that can lead to high employee performance (Delery & Roumpi, 2017).

The proposed conceptual model is shown in Fig. 1.

2.2The relationships between high-performance human resource management practices, affective commitment, and readiness for changeHPHRMP are consistent practices that enhance employees' skills, participation in decision making, and motivation to put forth their effort (Appelbaum et al., 2000; Sun, Aryee & Law, 2007). They include, among others, strict selective staffing, extensive training and development, performance-based evaluation, communication, and incentivized compensations contribution (Huselid, 1995; Lepak, Liao, Chung & Harden, 2006; Wright & Snell, 1991). According to Vivek (2018), HPHRMP can be categorized considering four sub-functions: a) selection, b) training, c) evaluation, and d) compensation. HPHRMP, and, particularly, high-performance systems of practices, can result in superior indicators of firm performance and sustainable competitive advantage (Way, 2002).

Affective commitment can be defined as “a partisan, affective attachment to the goals and values of an organization, to one's role in relation to goals and values, and to the organization for its own sake, apart from its purely instrumental worth” (Buchanan, 1974: 533). It is a type of commitment achieved when individuals fully embrace the organization's goals and values (Vila Vázquez, Castro Casal & Álvarez Pérez, 2016).

Affectively committed employees are emotionally involved in the organization and feel personally responsible for its level of success. They usually display positive work attitudes, a desire to stay with the organization, and high levels of performance (Meyer & Allen, 1997).

The extent employees perceive that employers value their contributions and care about their wellbeing, that is, perceived organizational support (POS), considers the organization's support to the employee (Eisenberger, Fasolo & Tro, 1990). Through POS, employees receive information about justice and fairness in the workplace (Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002). The presence of POS creates a kind of obligation to care for the organization which results in organizational commitment (Eisenberger, Armeli, Rexwinkel, Lynch & Rhoades, 2001).

Researchers have noted that the effective implementation of HPHRMP lead employees to perceive a supportive environment (García Chas, Neira Fontela & Varela Neira, 2012; Wright, Gardner & Moynihan, 2003). As HPHRMP enhance organizational communication with employees, they can be viewed as tangible concrete programs intended at producing employee support (Alqudah, n.d.). In line with the SET points, perceived support would make that employees reciprocate in kind, and commitment with the organization is the output of that exchange (Guzzo & Noonan, 1994).

Particularly, different studies have noted that employee perspectives of HPHRMP have a positive effect on affective commitment. Mao, Song and Han (2013) have found a positive effect of HPHRMP on affective commitment, suggesting that employees’ attitudes can be improved by integrating effective high-performance work systems in the working environment. Wu and Chaturvedi (2009) explored the link between HPHRMP and employee attitudes, finding a direct and positive relationship between HPHRMP and affective commitment at the individual level. Scheible and Bastos (2013) and Conway and Monks (2008) also found a strong and positive relationship between employees' perceptions of HRM practices and affective commitment.

Taking these considerations into account, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1. High-performance HRM practices are positively related to affective commitment.

Managing employee attitude towards change with more readiness and less resistance is a primary plan for any change effort (Maheshwari & Vohra, 2015). As there exists a strong association between HRM practices and employee behavior (Mossholder, Richardson & Settoon, 2011), HR function can become an important change enabler within the organization (Maheshwari & Vohra, 2015).

Researchers have examined different attitudinal constructs that express employees' attitudes towards organizational change, enhance employees’ acceptance, and support organizational change initiatives, such as readiness for change (Choi & Ruona, 2010).

Readiness for change, understood as “beliefs, attitudes, and intentions of change targeted members concerning the need for and capability of implementing organizational change” (Armenakis & Fredenberger, 1997: 144), is the primary factor guiding the implementation of effective and successful organizational changes (Armenakis & Harris, 2002).

When individuals demonstrate a high level of readiness, they will be more likely to change their behaviours to support the change initiative. The successful implementation of organizational change and performance is determined by the willingness to adopt change (Jones, Jimmieson & Griffith, 2005).

SET theory is also useful to understand the relationship between HPHRMP and employees’ readiness for change. If employees view HPHRMP as benefits received from their organization, they reciprocate those benefits by engaging various positive attitudes (Saifulina, Carballo-Penela & Ruzo-Sanmartin, 2021; Zhang et al., 2019) and discretionary role behaviours (Vu, Nguyen & Le, 2020) to support organizational goals (Eisenberger et al., 1990; Vu et al., 2020).

In this line, García-Chas, Neira-Fontela and Varela-Neira (2016) claimed that HPHRMP like employment security, training and development, and promotion opportunities might communicate positive signals to the employees that the organization values the employees and invests in them. Takeuchi, Lepak, Wang and Takeuchi (2007) added that HRM practices, such as rigorous recruiting and selection, training, empowerment in decision-making, high wages, and extensive benefits, may indicate the same message. When employees perceive HRM practices as investment, appreciation, and recognition, they will start to see themselves in a social exchange rather than a purely mercantile relationship (Shore & Shore, 1995).

Scholars have noted that some HPHRMP shape employees’ attitudes to change. High-performance HR communication practices play a key role in increasing employees readiness for change, as communication of the proposed change is the principal mechanism for causing organizational members willing and ready for change (Armenakis & Harris, 2002; Bernerth, 2004). Employees who received useful, timely, and relevant information about organizational change perceive the change more positively and were more willing to keep pace with and support the change process (Hameed, Khan, Sabharwal, Arain & Hameed, 2017; Wanberg & Banas, 2000).

The extent to which employees are supported to participate in the change process is also a fundamental dimension of this process (Holt, Armenakis, Feild & Harris, 2007). HRM participation practices encouraging employees to participate and enlist their contributions, consistently enhance employees commitment and performance, reduce their resistance to change, and makes them more willing to accept even unfavorable decisions related to organizational change (Bouckenooghe & Devos, 2007; Greenberg, 1987; Wanberg & Banas, 2000).

Additionally, scholars have also noted that HPHRMP which enhance employee participation are particularly effective for producing readiness for change by improving employees’ proactivity and vitality (Tummers, Kruyen, Vijverberg & Voesenek, 2015). Shirom (2011) underlines those high levels of employees’ participation in decision-making procedures that enhance their work involvement and perceived level of self-control and stimulate proactive behavior and vitality.

Several studies have verified that readiness for change is enhanced by showing management support for the proposed change and capabilities to clearly communicate the proposed change's content (e.g., Armenakis, Harris & Mossholder, 1993; Cinite, Duxbury and Higgins (2009). Jones et al. (2005) stated that focusing on cohesion and morale through enhancing training and development, open communication, and participation in decision-making leads to employees' realization of the values of strong human relationships in their departments, thus leading to higher levels of readiness for change.

According to these observations, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 2. High-performance HRM Practices are positively related to readiness for change.

2.3The relationships between affective commitment, readiness for change, and employee performanceAny form of commitment obligates the individual to perform the behaviours specified within the terms of that commitment. Those behaviours can include all forms of support that the organization requires from employees (Meyer et al., 2007).

In a context of change, affective commitment can show employee's desire to support change (Meyer & Herscovitch, 2001). Affectively committed employees believe in the change and desire to contribute to its success. In contrast to employees with strong continuous commitment, whose commitment is based primarily on the perceived cost of failing to support the change, affectively committed employees are likely to see value in their course of action, being willing to do whatever is required to benefit the target of that action, including organizational change (Meyer et al., 2007). Besides, the likelihood of employees engaging in discretionary behavior, often needed to increase effectiveness of organizational change, is high when affective commitment is strong (Meyer & Herscovitch, 2001).

Some prior studies have empirically found that affective commitment can induce readiness for change. Qureshi and Waseem (2018) conducted a study among teaching and non-teaching staff of higher education institutions in Pakistan to examine the impact of employees' organizational commitment on readiness for change during the change process. The study concluded that affective commitment significantly influences readiness for change. McKay, Kuntz and Näswall (2013) explored the relationships between perceptions of change-related (affective commitment to a changing organization) and change readiness and resistance among employees of some changing organizations in New Zealand and Australia. They found that affective commitment was positively related to readiness for change.

Hypothesis 3. Affective commitment is positively related to readiness for change.

In HRM field, the AMO framework provides a detailed description of how HRM practices affect performance by influencing the aspects of employees' ability, motivation, and opportunities. Based on this model, individuals perform better if they possess the Ability and Motivation, and the work environment provides them with the Opportunity to participate (Boselie, 2010; Boxall & Purcell, 2003). Thus, the commonly repeated view is that some combination of an individual's ability (A), motivation (M), and opportunities (O) would result in employee performance (Kellner, Cafferkey & Townsend, 2019).

Prior research has underlined the role of readiness for change to enhance employees’ abilities, motivation, and participation, which lead to individual performance. Scaccia et al. (2015) point out that individuals ready for change possess the needed capacities required for the successful implementation of innovation. Readiness for change also alters the individuals' mindsets. The employee ready for change is aware of the importance of change and the benefits that will result from this change, whether at the individual level or at the organization level. Hence, readiness will generate the motivation to obtain the opportunity to participate in the change and to perform well within the role assigned to him in the change process (Chrisanty, Gunawan, Wijayanti & Soetjipto, 2021).

In this line, some studies have showed a positive relationship between readiness for change and employee performance. Asbari, Hidayat and Purwanto (2021) investigated the effect of transformational leadership and readiness for change on employees’ performance in the Indonesian chemical industry. The results of this study confirmed that readiness for change and transformational leadership have a significant effect on employee performance.

Novitasari, Sasono and Asbari (2020) concluded that readiness for change has a positive and significant effect on the employee performance of the packaging industry employees in Indonesia. They also found that readiness for change positively mediates on the relationship between work-family conflict and employee performance.

Based on the previous considerations and in the AMO model assumptions, we formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4. Readiness for change is positively related to employee performance.

2.4The moderating role of hierarchy cultureCameron and Quinn (2006) described the organizational hierarchical culture as a formalized and structured culture, where managers excel at organization and coordination, and the tasks are managed based on definite procedures.

Organizations with hierarchical culture are typically based on control and power. They are stable, careful, and mature, and work is organized and systematic. Organizations with a strong hierarchical culture are solid, cautious, power-oriented, established, regulated, structured, and procedural (Wallach, 1983). They are usually characterized by conveying information with difficulty across managerial levels and by isolating the information at higher levels, as well as by less flexibility and more rigidity. They assume that control, stability, and predictability promote efficiency (Wei, Liu & Herndon, 2011; Zaltman, 1979).

We propose that the relationship between HPHRMP and affective commitment will negatively vary as a function of organizational hierarchy culture. That is, the positive relationship between HPHRMP and affective commitment will be weaker as hierarchy culture is stronger.

Employee perceptions of supportive environment induced by HPHRMP make possible a social exchange between employees and their organization, as employees wants to return back received benefits, feeling committed to the organization's goals (Blau, 1964).

However, employee's commitment would be adversely affected by any action taken to reduce individual responsibility (Salancik, 1977). Particularly, hierarchical structures do not benefit the commitment based in bonds of affection (Carvalho, Castro, Silva & Carvalho, 2018). As hierarchical structures involve standardized rules and policies as well as rigid organizational structures, centralization and restrictions inherent to hierarchy culture can reduce the perception of supportive environment that HPHRMP promote. The absence of POS would reduce employee's acceptance of organizational goals and values and also emotional attachment, identification, and involvement in the organization (Sommer, Bae & Luthans, 1996).

In this line, Sommer et al. (1996) found that the Korean workers in organizations with higher centralization of authority reported a lower level of organizational commitment. Goodman, Zammuto and Gifford (2001), examining the influence of organizational culture on the quality of work-life, found that hierarchical cultures were negatively associated with organizational commitment and job satisfaction.

According to these observations, the following hypothesis is therefore, proposed:

Hypothesis 5. Hierarchy Culture negatively moderates the relation of high-performance HRM practices and affective commitment.

3Methodology3.1Sample and data collection procedureData collection was conducted during the period from March 2020 to September 2020 among a population of bank employees in Jordan using a structured questionnaire. Bank employees were contacted through e-mail, phone, and personal contacts. From the 1398 questionnaires that were distributed, we obtained 510 valid questionnaires, yielding a response rate of 36.48%.

The study targeted all employees in the whole 25 banks operating in Jordan: 13 Jordanian commercial banks (67.3% of respondents), 8 foreign commercial banks (10.2% of respondents), 3 Jordanian Islamic banks (17.3% of respondents) and, finally, 1 foreign Islamic bank (1.2% of respondents). In addition, 1.7% were respondents from financial institutions other than banks, and 2.3% of respondents declined to mention their bank.

Regarding profile of respondents, six demographic variables were requested: age (18 to 29: 26.1%; 30 to 39: 43.5%; 40 to 49: 19.8%; 50 to 59: 10%; and 60 or over: 0.6%), gender (male: 68%; female: 32%), current status (active: 98.8%; retired: 1.2%); education (less than college diploma: 0.6%; community college diploma: 4.1%; bachelor's degree: 75.3%; master degree: 17.1%; PhD: 2.9%), experience in banking sector (less than 5 years: 19.2%, 5–10 years: 29.8%; 11–15 years: 22.2%; 16–20 years: 10.6%, 21–25 years: 9.0%; and 26 years or more: 9.2%), and finally, job position (lower: 39.6%, middle: 44.4%; upper: 16.0%).

Guidelines from Armstrong and Overton (1977) were followed to examine the possibility of nonresponse bias. We have searched for significant differences between early (the first 75% of returned questionnaires) and late respondents, the last 25% responses (Weiss & Heide, 1993). T-tests considering these two groups on several key firm features, such as year of establishment (p = 0.491), capital (p = 0.065), number of branches (p = 0.200), and number of employees (p = 0.126) were performed, and results do not show significant differences between respondents and non-respondents, at the 0.05 level, suggesting that nonresponse bias was not a problem.

Two different tests to determine the extent of variance were considered to check the existence of common method bias. The Harman one-factor test (Podsakoff & Organ, 1986) showed that a single general factor did not account for most variance in an exploratory factor analytic (only 20.01%), suggesting that the presence of common method variance was unlikely to be significant. Secondly, following Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff (2003) a new model with all the observed variables loading on one factor was re-estimated. The results were unacceptable (Chi-square = 14,128.944; df = 1430; RMSEA = 0.132). Thus, these results suggest that common method bias was not a problem in this study.

3.2MeasuresTo operationalize the variables, previously validated five-point Likert scales (1 = totally disagree; 5 = totally agree) were used in this research. HPHRMP were measured based on Sun et al. (2007), including the following practices: communication and clear job description, results-oriented appraisal, selective staffing, extensive training, and participation. Affective Commitment was measured based on Allen and Meyer (1990). Readiness for Change was measured based on Bouckenooghe, Devos and Van den Broeck (2009) and (Piderit, 2000). Employee Performance scale was adapted from Griffin, Neal and Parker (2007), and finally, hierarchy culture was measured based on K. S. Cameron and Quinn (2011).

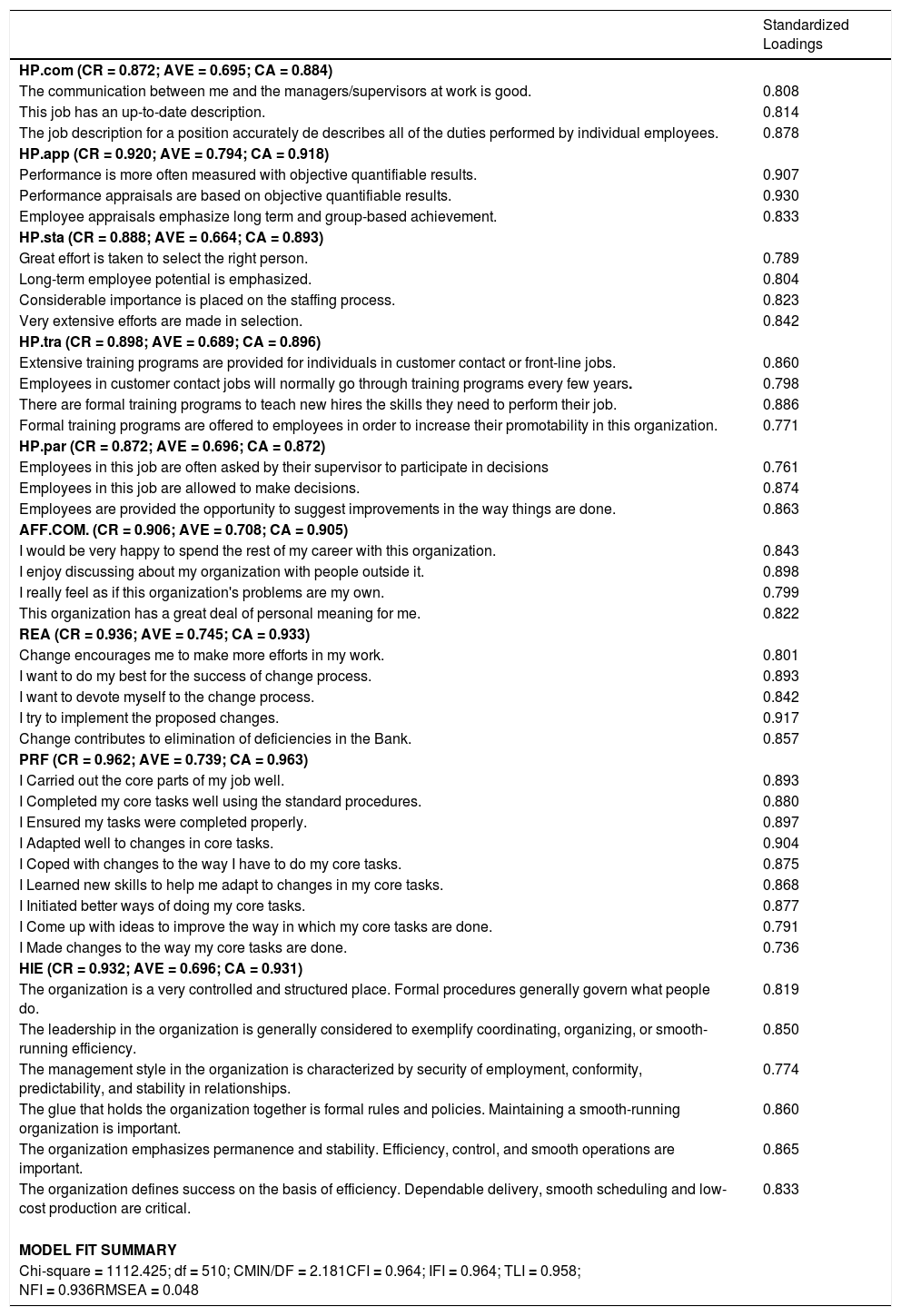

4Analysis and results4.1Reliability and validityA Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was carried out to analyze the psychometric properties of the scales, also assessing discriminant validity, convergent validity, and scale reliability (Gerbing & Anderson, 1988). Content validity was analysed through a comprehensive literature review and by consulting experienced practitioners, to ensure that the used measures meet the requirements for content validity. A pre-test with long-experience bank employees in the Jordanian banking sector was also performed.

Table 1 shows the results from CFA. Comparative fit index (CFI=0.964), incremental fit index (IFI=0.964), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI=0.958), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA=0.048) measures of fit are considered, being inside conventional cut-off values (Vandenberg & Lance, 2000).

Confirmatory factor analysis: Summary of measurement results, validity, and reliability.

| Standardized Loadings | |

|---|---|

| HP.com (CR = 0.872; AVE = 0.695; CA = 0.884) | |

| The communication between me and the managers/supervisors at work is good. | 0.808 |

| This job has an up-to-date description. | 0.814 |

| The job description for a position accurately de describes all of the duties performed by individual employees. | 0.878 |

| HP.app (CR = 0.920; AVE = 0.794; CA = 0.918) | |

| Performance is more often measured with objective quantifiable results. | 0.907 |

| Performance appraisals are based on objective quantifiable results. | 0.930 |

| Employee appraisals emphasize long term and group-based achievement. | 0.833 |

| HP.sta (CR = 0.888; AVE = 0.664; CA = 0.893) | |

| Great effort is taken to select the right person. | 0.789 |

| Long-term employee potential is emphasized. | 0.804 |

| Considerable importance is placed on the staffing process. | 0.823 |

| Very extensive efforts are made in selection. | 0.842 |

| HP.tra (CR = 0.898; AVE = 0.689; CA = 0.896) | |

| Extensive training programs are provided for individuals in customer contact or front-line jobs. | 0.860 |

| Employees in customer contact jobs will normally go through training programs every few years. | 0.798 |

| There are formal training programs to teach new hires the skills they need to perform their job. | 0.886 |

| Formal training programs are offered to employees in order to increase their promotability in this organization. | 0.771 |

| HP.par (CR = 0.872; AVE = 0.696; CA = 0.872) | |

| Employees in this job are often asked by their supervisor to participate in decisions | 0.761 |

| Employees in this job are allowed to make decisions. | 0.874 |

| Employees are provided the opportunity to suggest improvements in the way things are done. | 0.863 |

| AFF.COM. (CR = 0.906; AVE = 0.708; CA = 0.905) | |

| I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career with this organization. | 0.843 |

| I enjoy discussing about my organization with people outside it. | 0.898 |

| I really feel as if this organization's problems are my own. | 0.799 |

| This organization has a great deal of personal meaning for me. | 0.822 |

| REA (CR = 0.936; AVE = 0.745; CA = 0.933) | |

| Change encourages me to make more efforts in my work. | 0.801 |

| I want to do my best for the success of change process. | 0.893 |

| I want to devote myself to the change process. | 0.842 |

| I try to implement the proposed changes. | 0.917 |

| Change contributes to elimination of deficiencies in the Bank. | 0.857 |

| PRF (CR = 0.962; AVE = 0.739; CA = 0.963) | |

| I Carried out the core parts of my job well. | 0.893 |

| I Completed my core tasks well using the standard procedures. | 0.880 |

| I Ensured my tasks were completed properly. | 0.897 |

| I Adapted well to changes in core tasks. | 0.904 |

| I Coped with changes to the way I have to do my core tasks. | 0.875 |

| I Learned new skills to help me adapt to changes in my core tasks. | 0.868 |

| I Initiated better ways of doing my core tasks. | 0.877 |

| I Come up with ideas to improve the way in which my core tasks are done. | 0.791 |

| I Made changes to the way my core tasks are done. | 0.736 |

| HIE (CR = 0.932; AVE = 0.696; CA = 0.931) | |

| The organization is a very controlled and structured place. Formal procedures generally govern what people do. | 0.819 |

| The leadership in the organization is generally considered to exemplify coordinating, organizing, or smooth-running efficiency. | 0.850 |

| The management style in the organization is characterized by security of employment, conformity, predictability, and stability in relationships. | 0.774 |

| The glue that holds the organization together is formal rules and policies. Maintaining a smooth-running organization is important. | 0.860 |

| The organization emphasizes permanence and stability. Efficiency, control, and smooth operations are important. | 0.865 |

| The organization defines success on the basis of efficiency. Dependable delivery, smooth scheduling and low-cost production are critical. | 0.833 |

| MODEL FIT SUMMARY | |

| Chi-square = 1112.425; df = 510; CMIN/DF = 2.181CFI = 0.964; IFI = 0.964; TLI = 0.958; NFI = 0.936RMSEA = 0.048 |

Note:CR: Composite Reliability; AVE: Average Variance Extracted; CA: Cronbach Alpha.

Notation:HP.com: Communication and Clear Job Description; HP.app: Results-Oriented Appraisal; HP.sta: Selective Staffing; HP.tra: Extensive Training; HP.par: Participation; AFF.COM: Affective Commitment; REA: Readiness for Change; PRF: Employee Performance; HIE: Hierarchy Culture.

Individual loadings are considered to observe convergent validity. The results show that every item load on their specified latent variables and that each loading is large and significant, showing convergent validity (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988).

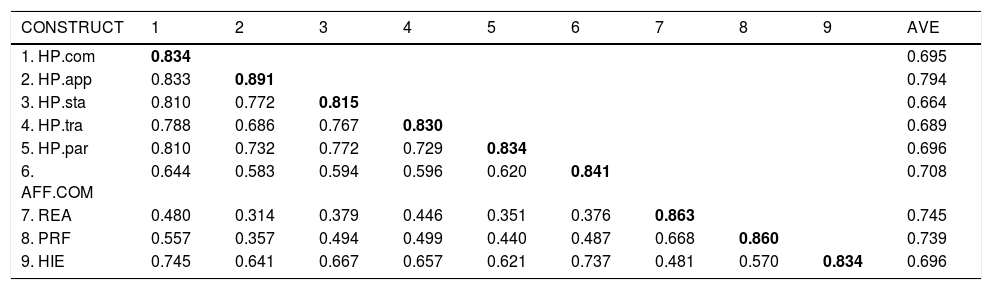

Construct intercorrelations were observed in order to check for discriminant validity, so they were significantly different from 1 and shared variance between any two constructs was less than the average variance explained in the items by the construct (Fornell & Larcker, 1981) (Table 2).

Confirmatory Factor Analysis: correlations between constructs and average variance extracted.

| CONSTRUCT | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. HP.com | 0.834 | 0.695 | ||||||||

| 2. HP.app | 0.833 | 0.891 | 0.794 | |||||||

| 3. HP.sta | 0.810 | 0.772 | 0.815 | 0.664 | ||||||

| 4. HP.tra | 0.788 | 0.686 | 0.767 | 0.830 | 0.689 | |||||

| 5. HP.par | 0.810 | 0.732 | 0.772 | 0.729 | 0.834 | 0.696 | ||||

| 6. AFF.COM | 0.644 | 0.583 | 0.594 | 0.596 | 0.620 | 0.841 | 0.708 | |||

| 7. REA | 0.480 | 0.314 | 0.379 | 0.446 | 0.351 | 0.376 | 0.863 | 0.745 | ||

| 8. PRF | 0.557 | 0.357 | 0.494 | 0.499 | 0.440 | 0.487 | 0.668 | 0.860 | 0.739 | |

| 9. HIE | 0.745 | 0.641 | 0.667 | 0.657 | 0.621 | 0.737 | 0.481 | 0.570 | 0.834 | 0.696 |

Note: Diagonal is the square root of the AVE.

Notation: HP.com: Communication and Clear Job Description; HP.app: Results-Oriented Appraisal; HP.sta: Selective Staffing; HP.tra: Extensive Training; HP.par: Participation; AFF.COM: Affective Commitment; REA: Readiness for Change; PRF: Employee Performance; HIE: Hierarchy Culture.

Finally, all constructs presented acceptable levels of composite reliability (CR), exceeding the threshold of 0.60 suggested by Bagozzi and Yi (1988) (Table 1). Besides, all latent variables exceeded the recommended level of the average variance extracted (0.50). Therefore, results show that the used scales were reliable in terms of how the measurement model was specified for all latent variables.

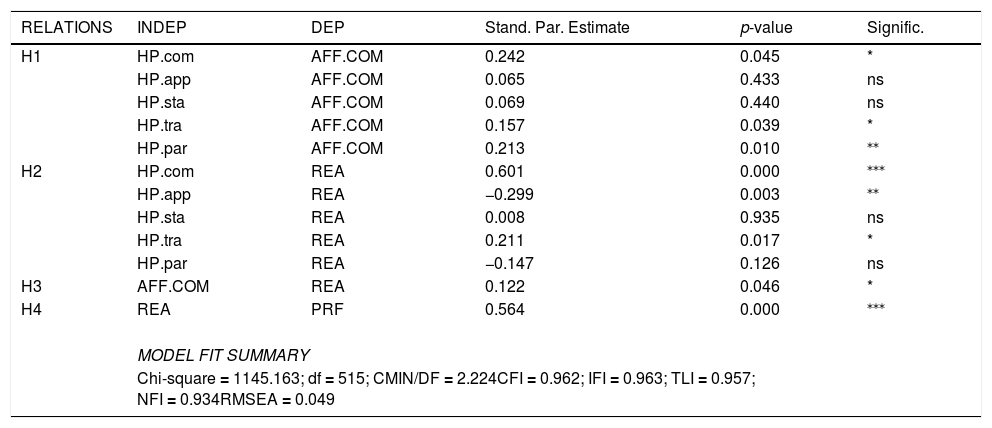

4.2Testing of hypothesisOn the one hand, Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) using the maximum likelihood method was used to test the direct relationships between the different constructs at the same time (Table 3).

Direct effects: model fit summary and standardized parameters estimates.

| RELATIONS | INDEP | DEP | Stand. Par. Estimate | p-value | Signific. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | HP.com | AFF.COM | 0.242 | 0.045 | * |

| HP.app | AFF.COM | 0.065 | 0.433 | ns | |

| HP.sta | AFF.COM | 0.069 | 0.440 | ns | |

| HP.tra | AFF.COM | 0.157 | 0.039 | * | |

| HP.par | AFF.COM | 0.213 | 0.010 | ⁎⁎ | |

| H2 | HP.com | REA | 0.601 | 0.000 | ⁎⁎⁎ |

| HP.app | REA | −0.299 | 0.003 | ⁎⁎ | |

| HP.sta | REA | 0.008 | 0.935 | ns | |

| HP.tra | REA | 0.211 | 0.017 | * | |

| HP.par | REA | −0.147 | 0.126 | ns | |

| H3 | AFF.COM | REA | 0.122 | 0.046 | * |

| H4 | REA | PRF | 0.564 | 0.000 | ⁎⁎⁎ |

| MODEL FIT SUMMARY | |||||

| Chi-square = 1145.163; df = 515; CMIN/DF = 2.224CFI = 0.962; IFI = 0.963; TLI = 0.957; NFI = 0.934RMSEA = 0.049 | |||||

Note:.

Results show that the fit indexes met the conventional threshold values (Vandenberg & Lance, 2000): CFI = 0.962; IFI = 0.963; TLI = 0.957; RMSEA = 0.049.

Regarding the hypotheses proposed in the research model, starting with Hypothesis 1, the positive influence of HPHRMP on affective commitment is supported on the following practices: communication and clear job description, which returned an estimated coefficient of 0.242 (p < 0.05), extensive training, (0.157; p < 0.05), and participation (0.213; p < 0.01). However, the results show that results-oriented appraisal, and selective staffing are not significantly related to affective commitment.

Regarding Hypothesis 2, the positive influence of HPHRMP on readiness for change is supported for the following practices: communication and clear job description, with an estimated coefficient of 0.601 (p < 0.001), and training, (0.211; p < 0.05). The positive relationship is not supported for results-oriented appraisal, selective staffing, and participation practices.

Supporting Hypothesis 3, affective commitment also showed a positive and significant effect on readiness for change, with an estimated coefficient of 0.122 (p < 0.05). Finally, our findings show that readiness for change has a positive and significant effect on employee performance (0.564; p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 4.

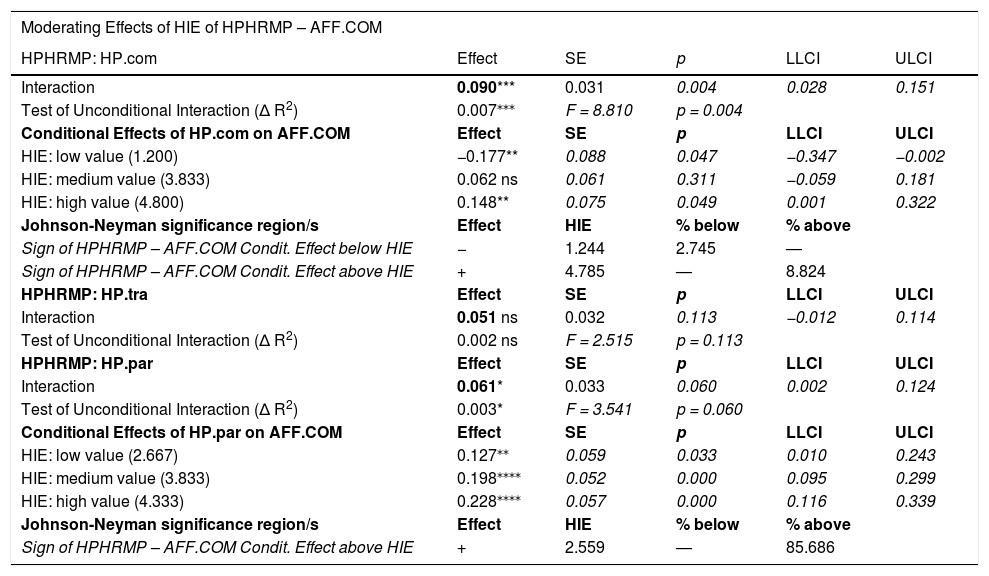

On the other hand, the approach of Hayes (2017), using the PROCESS macro for SPSS, was used to test the moderating hypothesis. A moderated analysis for each HPHRMP with significant influence on affective commitment was performed. This procedure is appropriate to analyze the mechanisms through which one variable influence another variable (Hayes, 2017). Besides, it allows for understanding the conditions in which this relationship happens. In addition, this procedure also allows for using bootstrap to avoid problems from the non-normal distribution of data. Bootstrap confidence intervals are particularly useful for testing hypotheses related to small samples (Preacher, Rucker & Hayes, 2007). Mean-centered variables have been used to easily interpret the coefficients (Hayes, 2017).

Table 4 shows the results of the estimated model, presenting, for each HPHRMP with significant influence on affective commitment, the non-standardized parameters and confidence intervals for interaction, as well as the test of unconditional interaction, the conditional effects of each HPHRMP on affective commitment at different values of the moderator (hierarchy culture), and, finally, the Johnson-Neyman significant region(s).

Moderating effects: parameters estimates and confidence intervals for interaction, test of unconditional interaction, conditional effects and Johnson-Neyman significance region/s.

| Moderating Effects of HIE of HPHRMP – AFF.COM | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPHRMP: HP.com | Effect | SE | p | LLCI | ULCI |

| Interaction | 0.090*** | 0.031 | 0.004 | 0.028 | 0.151 |

| Test of Unconditional Interaction (Δ R2) | 0.007⁎⁎⁎ | F = 8.810 | p = 0.004 | ||

| Conditional Effects of HP.com on AFF.COM | Effect | SE | p | LLCI | ULCI |

| HIE: low value (1.200) | −0.177** | 0.088 | 0.047 | −0.347 | −0.002 |

| HIE: medium value (3.833) | 0.062 ns | 0.061 | 0.311 | −0.059 | 0.181 |

| HIE: high value (4.800) | 0.148** | 0.075 | 0.049 | 0.001 | 0.322 |

| Johnson-Neyman significance region/s | Effect | HIE | % below | % above | |

| Sign of HPHRMP – AFF.COM Condit. Effect below HIE | − | 1.244 | 2.745 | — | |

| Sign of HPHRMP – AFF.COM Condit. Effect above HIE | + | 4.785 | — | 8.824 | |

| HPHRMP: HP.tra | Effect | SE | p | LLCI | ULCI |

| Interaction | 0.051 ns | 0.032 | 0.113 | −0.012 | 0.114 |

| Test of Unconditional Interaction (Δ R2) | 0.002 ns | F = 2.515 | p = 0.113 | ||

| HPHRMP: HP.par | Effect | SE | p | LLCI | ULCI |

| Interaction | 0.061* | 0.033 | 0.060 | 0.002 | 0.124 |

| Test of Unconditional Interaction (Δ R2) | 0.003* | F = 3.541 | p = 0.060 | ||

| Conditional Effects of HP.par on AFF.COM | Effect | SE | p | LLCI | ULCI |

| HIE: low value (2.667) | 0.127⁎⁎ | 0.059 | 0.033 | 0.010 | 0.243 |

| HIE: medium value (3.833) | 0.198⁎⁎⁎⁎ | 0.052 | 0.000 | 0.095 | 0.299 |

| HIE: high value (4.333) | 0.228⁎⁎⁎⁎ | 0.057 | 0.000 | 0.116 | 0.339 |

| Johnson-Neyman significance region/s | Effect | HIE | % below | % above | |

| Sign of HPHRMP – AFF.COM Condit. Effect above HIE | + | 2.559 | — | 85.686 | |

Note:.

p < 0.001; ns: not significant. Bootstrap confidence intervals derived from 5000 samples (95% level of confidence). Conditional values computed at 16th, 50th and 84th percentiles (except for HP.des.com, HIE low and high values considered below and above Johnson-Neyman significance regions). Notation:HPHRMP: High-performance HRM Practices; HP.com: Communication and Clear Job Description; HP.tra: Extensive Training; HP.par: Participation; AFF.COM: Affective Commitment; REA: Readiness for Change; PRF: Employee Performance; HIE: Hierarchy Culture.

Results show that hierarchy culture moderates the relationship between communication and clear job description and affective commitment (0.090, p < 0.01). It also moderates the relationship between participation and affective commitment (0.061, p < 0.10). The coefficients of the interaction are significant and positive; confidence intervals computed by bootstrapping do not include zero value, and, finally, tests of unconditional interaction are also significant in both cases. The confidence intervals estimated for the conditional effects of communication and clear job description on affective commitment, as well as for the conditional effects of participation on affective commitment, at different values of hierarchy culture, provide additional support for this moderating effect.

Therefore, these results show that hierarchy culture positively moderates the relationship between communication and clear job description and affective commitment, as well as the relationship between participation and affective commitment, but this moderating effect is not as it was described in Hypothesis 5.

Lastly, our findings also show that hierarchy does not moderate the relationship between extensive training and affective commitment, since neither coefficient of the interaction (0.051, p = 0.113, and confidence intervals computed by bootstrapping include zero value), nor test of unconditional interaction, are significant. Hence, the results do not support the proposed hypothesis of moderation of hierarchy culture between extensive training and affective commitment (Hypothesis 5).

5Discussion, limitations, and future research5.1DiscussionThe results of this study provide support to most of our hypotheses. Regarding the role of HPHRMP in promoting employees’ affective commitment, our findings show that Hypothesis 1 is partially supported. As it was hypothesized, results show that the implementation of HPHRMP related to communication and clear job description, extensive training, and participation increases employees’ affective commitment. In line with SET theory (Blau, 1964), this result could suggest that employees perceive these practices as supportive ones, which lead them to reciprocate to that support in terms of affective commitment.

On the other hand, results also show that result-oriented appraisal and selective-staffing practices are not useful to enhance employee affective commitment. Results-oriented appraisal practices underline that appraisal are based on quantifiable objectives and results. While an objective assessment of employee performance could be perceived as positive by them, these practices involve an assessment of their performance which could not always be perceived as a strong sign of support if the results of assessment are not positive.

As selective staffing practices affect to employees before they are hired, the present employees could not perceive these practices as supportive as communication and clear job description, extensive training, and participation. Besides, Jordan and other Arabic countries have a tribal-structured society. The tribal nature of society strongly influences the social and economic environment of Jordan (Branine & Analoui, 2006; Rowland, 2009; Sharp, 2013). Tribalism plays an influential role in the nomination, recruitment, selection for jobs, and deployment of employees. Many employees are selected based on their relationship with the owners or managers of the organization. Selection and recruitment process tend to neglect merit, competence or qualifications principles required in job candidates (Aladwan, Bhanugopan & Fish, 2014; Budhwar, Mellahi, Budhwar & Mellahi, 2006). As selective staffing practices could be against tribal values inherent to Jordan society, they could not be perceived as supportive ones.

Secondly, results also show that both communication and clear job description, and extensive training HPHRMP could directly produce readiness for change (Hypothesis 2). In line with SET theory, this result could suggest that when employees perceive these practices as benefits, they will reciprocate them by engaging positive attitudes to support organizational goals, including those goals related to change. Prior research have highlighted that those practices related to communication, as communication and training, produce this positive effect (García-Chas et al., 2016; Shore & Shore, 1995).

Contrary to theoretical formulations, our findings underline that employee perceptions of result-oriented appraisal practices are negatively associated to readiness for change. An objective assessment of employee performance could not be always perceived as positive by employees, particularly in countries like Jordan, where many workplace relations rely on favouritisms or wasta rather than legitimate rights or employees’ ability to compete (Loewe, Blume & Speer, 2008). Our findings suggest that result-oriented appraisal practices produce negative attitudes to support organizational change.

Practices aimed to promote selective-staffing and employee participation are not statistically significant related to readiness for change. As we previously highlighted, the importance of selective staffing practices for the current employees could be attenuated by the fact that these practices (1) mainly affect to employees before they are hired, probably being less relevant for some current employees, and (2) could be against tribal values inherent to Jordan society.

Encouraging workforce participation is not neither relevant to promote readiness for change. Prior research has noted that enhancing employees’ participation improves their vitality and proactivity, which are important for their readiness for change (Tummers et al., 2015). As this research is focused in one occupation and country, contextual factors can explain this finding. Studies on Islamic HRM (e.g., Mellahi & Budhwar, 2010; Tayeb, 1997) have highlighted that Islamic culture, values, and norms in the workplace could influence HRM practices. The role of participation practices could be different in Islamic than Western countries. However, additional studies are needed to confirm this point.

Our findings also show a positive and statistically significant relationship between affective commitment and readiness for change (Hypothesis 3). This finding is in line with research which underlines that affectively committed employees are willing to do what is required to benefit their organization, what includes organizational change, when change process is required (McKay et al., 2013; Meyer et al., 2007; Qureshi & Waseem, 2018).

Regarding the relationship between readiness for change and employee performance, our findings found a positive relationship between both constructs (Hypothesis 4). Under the AMO framework, this result could be explained considering that readiness for change involves possessing some capacities needed for implementing change (Scaccia et al., 2015), also producing motivation to get the opportunity to participate in the change process (Chrisanty et al., 2021). We think that this is an interesting finding. Although a few studies have examined the influence of readiness for change on employee performance, this relationship has been largely ignored.

Results also show that hierarchy culture moderates the relationship between HPHRMP and affective commitment when considering HPHRMP related to communication and clear job description and to employee participation (Hypothesis 5). However, this moderation effect is different from what it was hypothesized. Considering that standardized rules, control, and orientation to power inherent to hierarchy culture could reduce employees perceived support, we expected that hierarchy culture attenuates the positive effect of HPHRMP in affective commitment. However, the results show that hierarchy culture positively reinforces the effect of these HPHRMP on affective commitment.

This finding is consistent with the importance of hierarchy in Jordan national culture. According to Hofstede's classification of national cultures, Jordan is a hierarchical society where hierarchical order no needs further justification and is socially accepted. In the Jordanian organizational context, employees expect to be told what to do and centralization is popular (Hofstede, 2009). Although in some countries hierarchical structures could reduce the perception of supportive environment that HPRMP promote, it seems that the alignment with national culture makes that organizational hierarchy culture contributes to create a supportive environment for Jordanian employees, which reinforces the effect of some HPHRMP on affective commitment.

Results also show that hierarchy culture does not moderate the relationship between HPHRMP and affective commitment when considering extensive training practices. This result suggests that the role of hierarchy culture in this relationship varies depending on the considered HPHRMP.

5.2Managerial implicationsThe findings of this study are useful to those firms interested in using HPHRMP to improve some employees’ outcomes and promote organizational change.

First, we demonstrate that the implementation of some HPHRMP contribute to increase employee affective commitment and readiness for change, providing managers with useful information on what practice should they focus their efforts to achieve the expected outcomes. Our results show that HPHRMP related to 1) communication and clear job description, 2) extensive training, and 3) participation positively influence affective commitment. Communication and clear job description and extensive training practices also produce employees’ readiness for change.

Although, in theory, other HPHRMP could produce similar effects on affective commitment and readiness for change, this does not happen in the context of this study. We believe that this is an interesting point. Some studied banks are international banks operating in Jordan and HR managers could be from countries where the studied practices play a different role. As most of the studies on the consequences of HPHRMP are developed in Western countries, this finding could suggest that the context of the study influence the effects of HPHRMP by, for instance, affecting the perception of the implemented practices by employees. Managers should be aware of this to implement effective HPHRMP.

In a similar way, results show that the role of hierarchy culture moderating the relationship between HPHRMP and affective commitment varies depending on the considered practice. In this case, hierarchy culture does not moderate the proposed relationship when extensive training practices are implemented. Managers should be also aware of this different role when making decisions about the organizational culture in Jordan banks.

Second, showing that readiness for change positively influences employees’ performance could encourage managers to initiate change process. Although the importance of change for organizations success has increased dramatically (Burnes, 2009), organizational change has proved to be difficult to achieve (Burnes & Jackson, 2011) and most of organizational change initiatives failed to produce the intended outcomes (Beer & Nohria, 2000). Consequently, some organizations are reluctant to initiate change. This study shows that if managers promote employee's readiness for change, they could improve employee's performance, besides contributing to organizational change.

Finally, managers should be also aware that, contrary to some theoretical propositions, hierarchy culture could intensify the positive effect of HPHRMP in affective commitment.

In organizations where hierarchy or bureaucratic cultures are dominant, managers may be tempted to introduce more people-oriented cultures into the workplace, particularly when companies are involved in change process. More people-oriented cultures would allow that perceived support from HPHRMP increase employee affective commitment. In turn, this may benefit readiness for change and individual performance.

While promoting more people-oriented cultures could produce the desired effects in some contexts, our findings show that hierarchy cultures also could produce the same effect in different ones.

In this line, this work has highlighted that certain characteristics, such as tribalism and national culture, could shape the role of HRM, and particularly, HPHRMP in Jordan and other Arabic countries sharing similar country cultural characteristics. We think this is an interesting finding of this study, making appealing to further analyze if HRM play the same role in promoting organizational change in Arabic countries than in Western countries.

5.3Limitations and future research suggestionsThe present study has some limitations that it is necessary to mention. Firstly, this research only considers affective commitment, one of the components of organizational commitment (Meyer & Allen, 1991). As organizational commitment also includes normative and continuous commitment (Ben Moussa & El Arbi, 2020) future research could test if the other components play a similar role than affective commitment in the proposed model. Although each component can be seen as a function of different antecedents and produce different outcomes (Meyer & Allen, 1991), there is some evidence that normative and, at less extent, continuance commitment, could play a similar role than affective commitment in the proposed research model (Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch & Topolnytsky, 2002).

Secondly, the limitation of our study to bank employees in Jordan opens the debate of generalizability of our results. Differences regarding the development and importance of HRM management in different countries or national culture differences could influence the obtained findings .

Although considering a non-studied country fills a research gap, future research should test this model in different countries from Jordan. Cross-country studies could be useful to analyze if some of the obtained findings are also valid in other nations. Testing the model in occupations where the considered variables operate in a different way will be also interesting, as well.

Thirdly, this study approaches performance from an individual perspective. Some researchers have pointed out that in interdependent systems individual's behavior have an impact on groups, teams, and the organization as a whole (e.g., Griffin et al., 2007). Nevertheless, most of the activities developed by banks employees included in the studied sample are independent of others and they mainly work individually without being organized in teams.

Another limitation arises from the fact that the methodological approach used in this analysis to examine the proposed relationships include direct and moderating effects, but no indirect effects. The main aim of this study is to examine the contribution of HPHRMP to promote readiness for change. As our findings show that different HPHRMP can play a different role in this and other proposed relationships, moderated mediation models focusing on particular HPHRMP should be considered in future research.

In addition, dependent and independent variables have been measured only considering perceptions of employees. This is the most feasible way of obtaining required information for this research, since publicly available information is not available. Although this procedure has been used in different works in the business context (e.g. Alvarez Gil, Burgos Jiménez & Céspedes Lorente, 2001; Aragón-Correa, 1998; Carballo‐Penela & Castromán‐Diz, 2015), and performed tests suggested that common method bias was not a problem in this study, future research could add to the employees’ perceptions the point of view of other relevant groups, as supervisors.

Finally, this study follows a cross-sectional design. Cross-sectional designs do not allow for examining either causal relationship among the studied variables and their evolution. However, the lack of studies examining the role of HRM practices to enhance organizational change, particularly, employees’ readiness for change, adds value to this cross-sectional study. We see it as a first step to analyze the proposed relationships, being interesting that future research using longitudinal designs may analyze causal relationships among the studied variables.