Moral hazard in an organization occurs when people make decisions and take a high risk for their own benefit, given that they would not have to bear all the negative ensuing consequences should they occur. This risk transferred to third parties is generally due to the catalysts that foster this risk, namely, information asymmetries, power, trust and temporality. The contribution of our research lies in the inclusion of moral decisions in project management, thus demonstrating the feasibility of a Moral Compliance Model (MCM). This model is a complement to legal compliance and allows a connection to be established between Risk Management, Governance & Compliance. In 2019, experimental action research, combined with a Plan-Do-Check-Action applied to a company, were used to perform the analysis. The findings show that implementing this moral model in organisations is possible. However, what moral hazard is needs to be shown, along with identifying moral hazard situations and planning how to introduce moral hazard into the risk management model in order to reduce its negative effect or, ideally, eliminate it. We provide an overview of risks, including those around moral dilemma decisions; moral hazard situations that will expand compliance to integrated compliance in which not only legal, but also moral aspects are identified and assessed. Incorporating ethical dilemmas in strategic decisions is a robust advance towards responsible businesses.

Traditionally, the profit maximisation culture has prevailed in companies, to the detriment or, at least, without taking into accounts the impact on the set of stakeholders’ interests (Freeman, Harrison, Wicks, Parmar, & De Colle, 2010). However, in recent years, it has evolved into a more inclusive business model (Harrison, Phillips, & Freeman, 2020). The way of managing organisations has likewise changed and is now aligned with stakeholders and not only shareholder interests.

However, the profit maximisation objective leading companies to increase the risk with a third party –stakeholders – has partly suffered the negative consequences of those decisions. Those actions have been the guideline for many organisations (Dowd, 2009), where most organisations have sought their own benefit without taking into account the harm caused to a third party. Some of these cases have resulted in financial scandals, such as the Enron (2001), Arthur Andersen (2001), Madoff (2008) and Barclays (2012) cases, where it should be noted that the inadequate control of moral hazard in business decisions leads to social inefficiency (Urionabarrenetxea, San-Jose, & Retolaza, 2016).

A moral hazard situation occurs when an agent has a greater propensity to take risks as the potential costs of assuming such risks will be borne by a third party. The moral hazard arises because the individual or the institution makes their decisions without having to assume all the potential negative consequences of their actions. Moral hazard, as a characteristic element inherent to the financial system, to the economy in general and to companies in particular, needs to be kept under control. Moral hazard catalyst factors, particularly information asymmetry (see Gonzalo, San-Jose, & Retolaza, 2021 for a further explanation on catalysts), make it difficult to visualize the moral hazard risk assumed by third parties . Therefore, self-control of this risk by organisations using control or guarantee systems is of a vital importance in order to avoid the risk resulting in third parties or stakeholders being harmed. The problem has been detected in this stage.

Even though moral hazard is not a new concept in economics, the ethical perspective adopted in this article is. Implementing a model that facilitates its management as a new risk category within the organisation's risk system is proposed. The possible solution has been shown at this stage. The differential studying of the moral hazard concept is based on its not being considered as a further one to which the organisations are exposed and, therefore, its mitigation is required to avoid potential impacts on the company. In this case, the moral hazard, as it is generated and transferred to third parties by the organisation, does not impact those directly generating the risk. Therefore, the sustainable and ethical behaviour towards its stakeholders is analysed and considered, thus justifying its management by the company.

Organisations’ risk management systems are currently integrated in the Risk Management, Governance & Compliance coordinated management models (Miller, 2017).

The Enterprise Risk Management (EMR) of the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO, 2004), its embracing the environmental, social and governance-related risk (COSO, 2018) and the ISO 31000 (International Organization for Standardization, 2018) standards provide a framework for the implementation of efficient and effective risk management systems that enable appropriate actions to be taken for better shareholder value protection. Albeit that taking a comprehensive approach to a broad spectrum of risks and their management has been an undeniable improvement in enterprise risk management in recent years (González, Santomil, & Herrera, 2020), those systems do not specifically envisage the identification or the management of the moral hazard.

Corporate government, by means of establishing policy and governance principles, allows structures to be designed to set and achieve the rganization's objectives as regards its shareholders and its stakeholders overall. Initiatives such as the Good Governance Code of Listed Companies (OECD, 2020) and voluntary regulations enable organisations to advance in the desired relationship with stakeholders by fostering voluntary social policies (Velasco, Gondra, Moneva, & Rivero, 2005) and ethical conduct (Arjoon, 2005; Caldwell & Karri, 2005; O'Brien, 2006). The corporate-governance concept has now been broadened and allows companies, which so wish, to position their structure, culture and guidelines in order to reflect their social nature and their ethical decision-making ability (Marsden, 2000), under the premise that a positive relationship with their stakeholders helps not only to achieve sustainable development, but also the sustainability of the organisations itself and provides it with long-term benefits (Scherer et al., 2013). This perspective implies the voluntary assumption of new management models that increases the responsibility of the organisation to stakeholders overall when decision making; and, therefore, moral hazard situations may emerge that will have to be addressed. The ethical deployment in the organisation requires moral hazards to be identified and managed (Arjoon (2005).

Companies are currently under significant pressure to integrally strengthen their risk management systems in all their areas of activity, including the risk of breach of the legal obligations (Hoyt & Liebenberg, 2011). Even though it is true that great progress has been made with the inclusion of organisations’ responsibilities towards third parties, through legal compliance (Börzel & Buzogány, 2019; Salguero-Caparrós, Pardo-Ferreira, Martínez-Rojas, & Rubio-Romero, 2020), the inclusion of the ethical perspective requires compliance to be broadened and reinforced. There should also be compliance of the voluntary obligations assumed by companies in their relationship with their stakeholders and new default risks, such as the moral hazards, will have to be incorporated. In this vein, there is a gap in the literature that has been previously exposed by both Gonzalo, San-Jose, & Retolaza, 2021, who identify situations of moral hazard (hereinafter SMH) in the organisations and pinpoint the moral hazard catalysts, and Feldman and Kaplan (2019), who analyse the existing ethical conduct that is detrimental to third parties. Thus, the need for organisations to better understand the situations that could entail repercussions on third parties, including those that could generate a moral hazard, so that the risk management is integral, is highlighted.

The main aim of this paper is to propose a moral compliance model that allows the moral hazard to be incorporated in the company's risk management system, linked to the relationship with their stakeholders and to the risks that can be induced when making decisions and checking their applicability. This model does not seek to be a risk configurator that conditions people's ethics, but rather a tool and series of organisation structural recommendations, that help to deploy the ethical commitments that the company has adopted in a voluntary and sustainable way to help people in the decision-making process.

Thus, the problem in question is the lack of identification and management of the moral hazard. The moral hazard is incurred by organisations as regards the stakeholders who are potentially impacted. We therefore propose the following research question. Is it possible to implement a model to manage moral hazard (called Moral Compliance Model, MCM) in the governance-risk-compliant approach? If so, we want to establish how that is possible. We will therefore answer three questions: How the Moral Risk can be identified and assessed (Risk management), what the decision process (Governance view) is, and how the rules are applied (Compliance).

Using the Moral Compliance Model (MCM) developed in this paper, we establish a model for the prevention and control of moral hazard in the management of the organisation, thus advancing in the literature on Enterprise Risk Management (EMR). It will show how the moral hazard can be managed and a socially responsible company achieved, in which integrated compliance including the moral, in addition to the legal, is implemented.

The article is divided into five sections, the first of which is the introduction. The second reviews the theoretical background, whilst the third reasons the methodology employed. Section Four discusses the results obtained from the empirical research conducted. It ends with the conclusions, limitations and future lines of research.

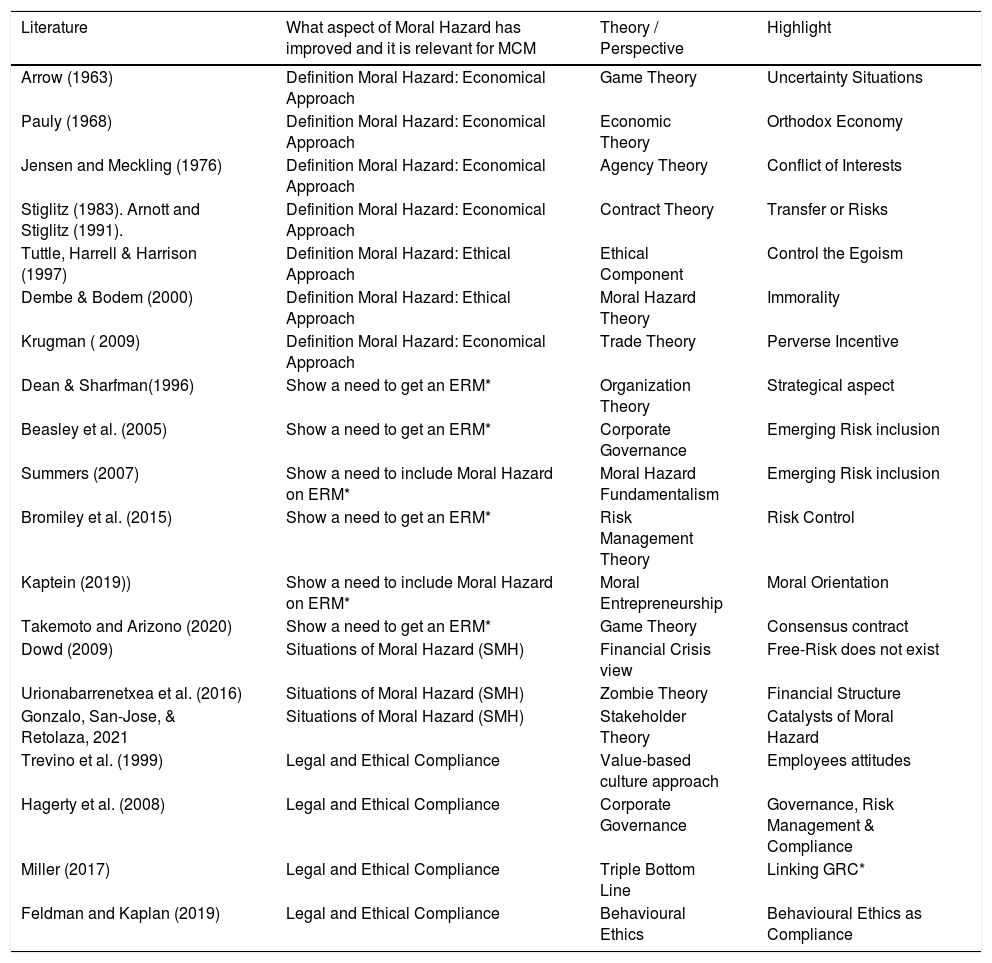

2Literature reviewPast and present moral hazard views need to be linked and corporate economic and ethical approaches integrated by means of a review of risk management literature. We first consider (see Table 1) the literature on traditional moral hazard based on economic theories, before moving on to a new ethical approach and then finish with the moral hazard situations in organisations; an aspect where legal compliance is completed with a moral view.

Moral Hazard Literature from economical and ethical approach: a review for implement a moral hazard model.

| Literature | What aspect of Moral Hazard has improved and it is relevant for MCM | Theory / Perspective | Highlight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arrow (1963) | Definition Moral Hazard: Economical Approach | Game Theory | Uncertainty Situations |

| Pauly (1968) | Definition Moral Hazard: Economical Approach | Economic Theory | Orthodox Economy |

| Jensen and Meckling (1976) | Definition Moral Hazard: Economical Approach | Agency Theory | Conflict of Interests |

| Stiglitz (1983). Arnott and Stiglitz (1991). | Definition Moral Hazard: Economical Approach | Contract Theory | Transfer or Risks |

| Tuttle, Harrell & Harrison (1997) | Definition Moral Hazard: Ethical Approach | Ethical Component | Control the Egoism |

| Dembe & Bodem (2000) | Definition Moral Hazard: Ethical Approach | Moral Hazard Theory | Immorality |

| Krugman ( 2009) | Definition Moral Hazard: Economical Approach | Trade Theory | Perverse Incentive |

| Dean & Sharfman(1996) | Show a need to get an ERM* | Organization Theory | Strategical aspect |

| Beasley et al. (2005) | Show a need to get an ERM* | Corporate Governance | Emerging Risk inclusion |

| Summers (2007) | Show a need to include Moral Hazard on ERM* | Moral Hazard Fundamentalism | Emerging Risk inclusion |

| Bromiley et al. (2015) | Show a need to get an ERM* | Risk Management Theory | Risk Control |

| Kaptein (2019)) | Show a need to include Moral Hazard on ERM* | Moral Entrepreneurship | Moral Orientation |

| Takemoto and Arizono (2020) | Show a need to get an ERM* | Game Theory | Consensus contract |

| Dowd (2009) | Situations of Moral Hazard (SMH) | Financial Crisis view | Free-Risk does not exist |

| Urionabarrenetxea et al. (2016) | Situations of Moral Hazard (SMH) | Zombie Theory | Financial Structure |

| Gonzalo, San-Jose, & Retolaza, 2021 | Situations of Moral Hazard (SMH) | Stakeholder Theory | Catalysts of Moral Hazard |

| Trevino et al. (1999) | Legal and Ethical Compliance | Value-based culture approach | Employees attitudes |

| Hagerty et al. (2008) | Legal and Ethical Compliance | Corporate Governance | Governance, Risk Management & Compliance |

| Miller (2017) | Legal and Ethical Compliance | Triple Bottom Line | Linking GRC* |

| Feldman and Kaplan (2019) | Legal and Ethical Compliance | Behavioural Ethics | Behavioural Ethics as Compliance |

*ERM: Enterprise Risk Management. GRC: Governance, Risk management, and Compliance.

Source: own elaboration.

From an economic approach, the interest in the study of moral hazard dates back to the early 1960s, within the context of decision making in conditions of uncertainty (Arrow, 1963, and Pauly, 1968). Moral hazard occurs when a person or entity engages in economic activity in order to obtain maximum results, whilst a third party assumes the cost of risk of this activity in the event of failure. Moral hazard therefore describes situations where there is a transfer or risk between economic agents who are directly linked either by a contractual relationship (Arnott & Stiglitz, 1991) or more specifically by means of a principal agent relationship (Jensen & Meckling, 1976), where the agents, who manage and can therefore generate risk, have more information regarding their shares than the principal, who bears the risk (Stiglitz, 1983). Recently, Krugman (2009) defines moral hazard as any situation in which one person makes the decision about how much risk to take, while someone else bears the cost if things go badly.

From an ethical approach, few authors contribute in this line. The cost of risk may also be passed on to third parties with no direct connection, such as the government, thereby extending the impact to public policy (Summers, 2007). In all instances of moral hazard, there is always one party that bears a risk that it has not explicitly assumed, placing it at a disadvantage in comparison with the active agents, who adjust their behaviour in order to obtain some form of benefit. This action has ethical and moral components as it is not a duty but a decision (Tuttle, Harrell, & Harrison, 1997). There is then an ethical component that makes decision-makers prioritize their own benefit over that of others, and egotistical considerations abound in those actions. Although this concept is addressed from an ethical perspective with moral connotations (Dembe & Boden, 2000), it can also be explained using orthodox economy tools, such as rational individual conduct (Pauly, 1968) or managerial view with risk control (Bromiley, McShane, Nair, & Rustambekov, 2015).

The benefit of implementing enterprise risk management systems (hereinafter ERM) that reduce the negative effects of risky actions on companies can therefore be concluded. The literature shows the utility of using ERM from a strategical view (Dean & Sharfman, 1996), but the importance of consensus when contracts are applied and relationships are developed is also shown (Takemoto & Arizono, 2020), along with the governance of the system to achieve the expected results on companies (Beasley, Clune, & Hermanson, 2005).

The analysis of moral hazard as a behaviour motivated by rational causes, pure egoism or as an unconscious behaviour, does not allow progress in its mitigation. The moral hazard needs to be analysed from an amoral perspective in order to manage it in the company (Summers, 2007; Kaptein, 2019). Some organisations then worry about their responsibility of assumed risk implemented with the aim to control those aspects. A moral hazard in organizations is confirmed (Dembe & Boden, 2000) and it will therefore, be useful to consider the moral responsibility of organizations and incorporate that risk in their organizational system, including governance and decision process. The deliberate inclusion of moral hazard control will reduce the harm to third parties that assume moral hazard effect without their knowledge and consent.

Although the insurance sector is one of the most widely studied in identifying situations of moral hazard (hereinafter SMH), the financial crisis highlighted many other SMHs and their impact on a far wide stakeholder group (Dowd, 2009). Other aspects, such as the financials structure of companies could also impact negatively and increase the probability of moral hazard situations arising, particularly in zombie companies (see Urionabarrenetxea et al., 2016 for further information). An earlier inductive study allowed for the identification of a finite list of moral hazard situations in order to establish their range (Gonzalo, San-Jose, & Retolaza, 2021). These SMHs occurred in relation to their varying stakeholders. The analysis identified four elements that SMHs cause in businesses, in line with previous findings (Gonzalo, San-Jose, & Retolaza, 2021: 8): information asymmetry (“transferring information in an incomplete or ambiguous way”), power asymmetry (“taking advantage of a position of power to force the other party to assume excessive risks in relation to the risk/benefit binomial”), trust asymmetry (“generating false expectations to a stakeholder, taking advantage of trust”) and temporality asymmetry (“the fact that the results obtained by both parties do not coincide in time means that the balance-of-power relationships are constantly changing, opening the door to possible opportunistic behaviours”).

Corporations, in general, have a lack of control of moral hazards with negative implications for companies and their stakeholders (Bromiley et al., 2015), fundamentally because the moral orientation is not clear, and economic interest prevails over the moral perspective, unless you open your eyes to moral decisions through a system of inclusion towards a moral oriented company. At the turn of the century, there was a call for the necessary inclusion of stakeholders’ interests in corporate governance and business management in order to maximise long-term corporate value (Jensen, 2001). Companies cannot ignore the pressure to balance economic and moral issues exerted by shareholders, potential investors and other market agents. In this sense, the focus and concerns surrounding governance are extended to third parties in a quest for a reasonable balance in managing the interests of stakeholders in general and not just shareholders.

In turn, and dealing specifically with enterprise risk management, Beasley et al. (2005) stressed the difficulties managers experience when attempting to include certain emerging risks within current frameworks, drawing attention to a serious problem of a practical nature; namely that companies are exposed to a series of risks that they are failing to manage in a fit and appropriate manner. With a moral model (MCM) that includes moral hazard situations and a risk management system, both aspects, the process of control risks from Bromiley et al. (2015) and the moral inclusion from Kaptein (2019)) could be interconnected to implement successfully the moral at the operational and strategical level of corporations.

Finally, it will be linked to compliance literature. Including ethical dilemmas is no new aspect (Trevino, Weaver, Gibson, & Toffler, 1999), but some authors, such as Feldman and Kaplan (2019), Miller (2017) and Hagerty, Hackbush, Gaughan, and Jacobson (2008) now show the importance of including ethical aspects in compliance process. Therefore, governance, risk management and compliance (GRC) will be connected to close the circle and obtain expected positive results.

In the light of the above, the following sections present a moral compliance model designed in accordance with the results of an earlier research project (Gonzalo, San-Jose, & Retolaza, 2021) and including Bromiley et al. (2015) risk control and Kaptein (2019)) moral orientation ideas.

3MethodologyThe research was conducted using Action Research methodology (Lewin, 1946). This author defines the process as “a spiral of steps, each of which is composed of a circle of planning, action, and fact finding about the result of the action” (Lewin, 1946: 38).

The process was centred on a single case study. Mutualia was selected for the application of the MCM, a mutual provident society operating throughout Spain, but mainly in the Basque Country. It works with the Spanish National Institute of Social Security and deals with traffic accidents, occupational diseases and economic benefits for common contingencies. Mutualia was chosen for a number of reasons. Firstly, due to the geographical area in which it operates and the fact that it is a medium-sized enterprise; secondly, because its trajectory has positioned it at the forefront of the mutual insurance sector in the Basque Country with a market share of just under 50%; thirdly, due to its ongoing commitment to excellence in management; finally, and of vital importance for the success of our project, the board of directors demonstrated their complete willinginess to cooperate with the project. This was essential for the application of our MCM model, as it involved practically all the departments in the company. The management team considered that the project provided an opportunity to convert the research team's prior know-how in moral hazard into an output that would have an immediate and practical impact on the organisation. Its success would depend on its practical feasibility and capacity to bring about real change to the company. In this sense, the readiness of the Mutualia board of directors to take part in the project was motivated by their desire to develop and apply management tools that can be used directly to identify and manage moral hazard. A further objective was to improve the company's sustainability standards by managing all the risks within the organisation, with a particular focus on those affecting third parties.

In turn, the research team was eager to move ahead with the development of management tools that would boost business ethics and will enhance sustainability in order to allow for the identification and management of moral hazard, thereby preventing businesses from impacting negatively on third parties. Therefore, the principal objective of the research was to validate the practical application of the MCM. Possible problems of practical implementation and potential improvements of the MCM would thus be identified, and that analysis would allow the generalization to be applied in other organizations. Furthermore, it seeks to analyse the compatibility of the MCM with the rest of the organization's management tools, thus enhancing the ease of use by the organization and its perceived usefulness. Objectivity has been guaranteed, since the result of the application has been decoupled and the variables that affect the process itself have controlled. Furthermore, the credibility of the analysis has been guaranteed by applying the model developed by Creswell (2007) to the research: epoch (the examination of bias), joint peer interviews, member verification, prolonged commitment to descriptions and "living" the experience. This method reflects a systematic process with an objective and results.

Although Rapopport (1970) defines the Action Research methodology as focusing on the objective, other authors such as Susman and Evered (1978) and Chein, Cook, and Harding (1948) highlight it as a cyclical process with 5 phases: diagnosis, action planning, action, evaluation and specific learning. Following the terminology of Chein et al. (1948) and the number of phases implemented by the research team working with the people in the organization, this research can be classified as "experimental action research" given that all the phases of the project were carried out in collaboration with the parties. Fig. 1 reflects the Action Research process, including systematic steps and outcomes of the model:

Source: Authors’ own

As the previous figure shows, the Experimental Action Research applied to the MCM comprised five phases, a description of each is given below:

1. Diagnosis. Governance determines the policies and procedures in order to achieve the goals set by the organisation, which are linked not only to business operations, but also to their relationship with stakeholders. The existence of corporate moral hazards indicates an imbalance in the corporate systems of companies that adopt sustainability principles and demonstrate a genuine concern for their stakeholders.

2. Action planning. The organisation will have to realign its goals, mission, vision and values with policies, decision-making systems, management tools, performance indicators, and internal and external auditing systems. Applying the MCM system will ensure compliance with the moral hazard governance directives the organisation voluntarily assumes, using the same risk management techniques applied to its other legal obligations. Prior to implementation, an action plan must be drawn up that takes into consideration existing legal compliance and risk management systems. This action plan must include the following: setting objectives, creating the team responsible, approval of the timeline and training in the MCM.

3. Action taking.

- •

The first stage of introducing the MCM into the organisation must include actions geared towards raising awareness and providing all members of the organisation, and, in particular, the senior management team, with an insight into moral hazard that will allow for its later identification.

- •

SMH identification. The organisation's strategic context and value generation process must be examined in order to identify possible SMHs associated with its stakeholders and the underlying variables (namely, asymmetries of information, power, temporality and confidence). Area managers will be required to identify the potential risks involved in their activity. Identification is based on multiple means, including a review of operational processes, goals, events, historical information analysis and the established verification indicators or lists.

- •

SMH analysis and assessment. This will be based on the following criteria: degree of severity of the impact on the affected stakeholder, the likelihood of occurrence and potential frequency. These actions must be carried out by the areas responsible for each risk.

- •

Monitoring system identification. Processes will be applied in order to identify and gauge the efficiency of existing moral hazard monitoring systems by the risk managers.

- •

Risk assessment. This involves comparing residual risk levels once the existing monitoring processes have been applied, in accordance with the defined risk criteria in accordance with defined risk tolerance criteria.

- •

Risk handling. Based on the risk appetite defined by the organisation, responses will be determined in order to deal with the risks. The organisation's response to the risks identified will in effect determine how third-party interests are conserved and the manner in which an organisation generates value.

4. Evaluation. This is jointly carried out by the research and management teams, as well as the persons responsible for Risk Management. This phase consists of analysing the impact of the new moral hazard management process. It also considers the possible inclusion of the MCM in the organisation's existing compliance and risk management structure. Furthermore, it studies the potential need to create new organisational structures and management tools for decision-making regarding these new risks.

5. Specific learning. This phase allows for improvements to the initial MCM process to be defined, thereby permitting its inclusion in the organisation's MCM and risk management system.

Each stage of the process required precise data and information which were obtained essentially from semi-structured interviews and focus groups. Interviews are an effective research tool when a complex analysis using detailed information is required. They also create a relaxed atmosphere that is conducive to data collection (Patton, 2002) and are particularly useful when facing new problems that require in-depth study. Semi-structured interviews were used in our research (Rowley, 2012). Twenty-one interviews were held with members of the management team between February and March 2019 (see Annex 1). Two focus group sessions were held in April 2019: the 21 members of the management team were present at the first group and 20 at the second. They were divided into working groups of 5 or 6 members, in line with Kitzinger's recommendations (1995) regarding group size and efficiency (see Table 2). The participants, all members of the management team, were selected due to their interest in the purpose of our study: they form part of the organisation's core group in terms of responsibilities and decision-making capacity and hold maximum responsibility for the stakeholders and promoting the organisation's policies (Barbour, 2008; Mason, 2017; Flick, 2018)

Technical sheet.

| Phase Number | Phase 1 | Phase 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Mutualia Company: a brief summary. | ||

| Mutualia is a non-profit business association with joint responsibility | ||

| Offer coverage to 390,000 working people: almost 50% of the worker's insurance market in the Basque country | ||

| Web: https://www.mutualia.eus/es/ | ||

| 599 employees (72% women) | ||

| Aim | Identification of situations of Moral hazard | Evaluation of Moral hazard |

| Nº Participants | 21 | 21 in the first and 20 in the second (the director E16JFO went to an operation after the first focus) |

| Profile | All members of the Management Team | All members of the Management Team |

| Analysis Method | Semi structured Interviews | Focus Group |

| Risk Managers | All | All |

| Used Communication Form | ||

| 65% on line | ||

| 30% in person | ||

| 5% by telephone | 100% in person | |

| Contact time/No. | Minimum and maximum used email: 1–3 | Focus Group 1: 2hours 12` |

| Focus Group 2: hours 20` | ||

| Transcribed | Yes | Yes |

| Execution period | ||

| February 2019 to March 2019 | 12 April 2019 (9.30 and 12.30) |

What follows is a discussion of the deliverables corresponding to Phases 3, 4 and 5. The initial phases – 1 and 2 – consisted of identifying the problem and planning possible solutions (they are shown in the introduction of the paper). We opted not to include them in our discussion due to a lack of space and the low level of generalisation owing to the highly specific nature of the organisation. Our discussion is therefore limited to the results of the actions to identify the moral hazard map, risk management methods and the learning system.

Phase 3: Action taken to establish Moral Hazard Map.

Although Mutualia is committed to its stakeholders and the quest for excellence in management, a number of SMHs were identified. Moral hazard was detected in the relationship with all the stakeholders identified in our project, namely the Company, Society, Suppliers, Employees, Patient Customers and Business Clients, indicating the dimension of this problem for Mutualia's management system. The identification and later assessment of the SMH allowed for an initial Moral Hazard Map to be drawn up. This document is essential in order to organise the information describing the corporate risks. After the research team analysed the data and shared the findings with Mutualia's senior management team, a total of 30 SMHs were identified, as listed in the Mutualia Moral Hazard Standard Situations Matrix (MHSSM) shown in Table 3. The SMH were presented in matrix format considering both the affected stakeholders and the four catalytic elements that cause SMHs in businesses. It is shown how is possible to identify, analyse and include Moral Hazard into the risk management system of the company. Table 3. Mutualia Moral Hazard Standard Situations Matrix.

Mutualia moral hazard standard situations matrix.

| Stakeholder | AI | AT | AP | AR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SITUATION OF MORAL HAZARD/ASYMMETRIES | Information | Temporality | Power | Responsibility | |

| COMPANY CLIENT | |||||

| PRE-SALE | Offering a product, service or solution in the knowledge that it may not satisfy the customer's needs, and failing to inform them beforehand. | X | X | ||

| PRE-SALE | Concealing information regarding the range of services provided using third party means. | X | |||

| COMMUNICATION | Failing to inform customers in the same manner of their rights and obligations as members of the mutual provident society, thereby jeopardising the homogeneity of the standard of information and service. | X | |||

| PATIENT- CUSTOMERS | |||||

| PROVISION OF SERVICE | Adopting decisions regarding the refusal or expiry of services (e.g. cessation of activity or care of sick minors) in the case of doubt regarding the application of regulations, based on the possibility that the interested party may opt not to take legal action with a potentially positive outcome as it would incur legal costs. This decision would benefit the mutual provident society and the system, to the detriment of the individual. | X | |||

| PROVISION OF SERVICE | Failing to inform users of the legal alternatives when claiming services. | X | |||

| PROVISION OF SERVICE | Lack of proactive actions: in other words, failing to check whether beneficiaries meet the entitlement requirements that would enable them to apply for benefits. Many people are unaware of the options open to them. | X | |||

| PROVISION OF SERVICE | Given that the final decision lies with the patients, there is a risk that they are not informed of all the alternatives available to them when adopting medical decisions. | X | X | ||

| PROVISION OF SERVICE | Prioritising patients in accordance with economic criteria; in particular, access to medical services based on sick leave expenditure. | X | |||

| EMPLOYEES | |||||

| SELECTION | During the selection process interview, failing to inform potential candidates of the difficulties (sector regulations) in hiring new employees, except in cases of replacement, thereby generating expectations that may not be met. | X | |||

| HIRING | Hiring people whose skills levels are higher than those required, using promises of future possibilities for promotion that we are unable to guarantee. | X | X | ||

| CAREER DEVELOPMENT | Offering training and career development options with no guarantees that these promises can be met. | X | |||

| CAREER DEVELOPMENT | Promoting employees without assessing their suitability for the post. | X | |||

| CAREER DEVELOPMENT | Offering a post or task without ensuring that the person has fully understood the implications of accepting said functions. | X | |||

| CAREER DEVELOPMENT | Promoting an annoying person for our own benefit, in the knowledge that there are other, more capable employees who would fit the post. | X | |||

| CAREER DEVELOPMENT | Creating ad hoc posts for people we wish to benefit. | X | |||

| CAREER DEVELOPMENT | Assigning training to specific persons in the knowledge that this would place them at a clear advantage over their co-workers in future internal promotion processes, failing to provide all staff with equal opportunities. | X | |||

| COMMUNICATION | Taking credit before superiors for ideas, projects and actions of colleagues, without acknowledging the person or persons that have carried out the work, thereby limiting their career development and “success”. | X | X | ||

| CONCILIATION MEASURES | Adopting decisions regarding conciliation measures without pre-determined criteria based on objectivity and equality. | X | X | ||

| LEADERSHIP | Avoiding responsibility by delegating in our subordinates’ decisions that we should take ourselves. | X | |||

| LEADERSHIP | Asking a member of staff to undertake a task without informing their superior, thereby preventing their work from receiving due recognition it successful, yet which would be taken into account in the event of failure. | X | X | ||

| LEADERSHIP | Asymmetrical distribution of workloads in accordance with the degree of confidence and commitment shown by other members of staff. | X | X | ||

| SUPPLIERS | |||||

| TENDER | Improving the financial terms and conditions of an agreement with a supplier for personal benefit, in the knowledge , knowing that this may impact negatively on the subcontracting chain and in turn on the quality of the service /product acquired. | X | X | ||

| TENDER | Contracts or supplies where the law does not require a tender, generating expectations regarding the continuation of supply without full guarantees thereto, in order to obtain acceptance of the terms and conditions set by the company. | X | X | ||

| CONTRACTING | Offering exaggerated consumption forecasts with wide margins (in order to save time and resources), and therefore taking advantage of beneficial rates to which we are not really entitled. | X | X | ||

| CONTRACTING | Influencing the supplier's selection of the team members who will provide you with the service requested. Altering the natural selection of some members over others. | X | |||

| CONTRACTING | In the case of tenders, including a series of requirements that are greater than the provisions of the law (environment,% of disabled workers) that the mutual provident society itself does not meet or is unable to handle. | X | |||

| CONTROL OF THE CONTRACTED SERVICE | Changing the terms and conditions of a contract after it has been awarded, thereby forcing the supplier to refuse the contract in the light of the possible consequences. | X | X | X | |

| SOCIETY | |||||

| SERVICE SUBCONTRACTING | Allocating services to a supplier without considering the conditions in which they will be provided, or waste management processes. | X | |||

| SERVICE SUBCONTRACTING | Adopting decisions that are potentially damaging for the environment at the expense of improving our financial results, albeit within the law. Delaying the introduction of environmental measures. | X | |||

| INVESTMENTS | Limiting considerations regarding investments in centres or services exclusively to economic criteria and failing to take into consideration accessibility requirements. | X |

This matrix is of great interest for our research process, as it generates a promising set of hypotheses regarding the issue of moral hazard, not only providing a considerably greater insight into this issue, but also favouring its prevention, or at least a reduction of its negative effects. During the final meeting of the management team to approve Mutualia's Moral Hazard Map, the members unanimously agreed that SMHs were potential problems within the scope of the organisation's activity. Four underlying factors were also identified as the causes for situations of moral hazard in the organisation: asymmetries of information, power, responsibility and temporality.

Phase 4: Evaluation of moral hazard in the risk management model.

Identifying SMHs enabled the organisation to manage its moral hazards. Steady progress has been made in this sense, based on PDCA methodology (Plan, Do, Check, Action). Each stage of the process has included periods of reflection that have generated proposals for ongoing improvements. The MCM has been included in the organisation's Risk Management Procedure Plan (see Fig. 2), following the same procedure as for the other risks detected, thereby adding to and improving this strategic process. However, a complete inclusion of moral hazard means that the creation of new organisational structures was essential to facilitate the feasibility of the moral hazard management system. Fundamentally, it consisted of applying ethical dilemma management to assist with decision-making processes, as well as the setting up of an Ethics Committee with a consultation, monitoring and response role in the event of ethical risks. The process of including legal and moral risks is practically complete, although the latter require committees with members with expertise in ethics in order to guarantee the correct monitoring and control of these risks. It contributes moral entrepreneurship because the outcomes include the moral development into the company in a structured and integrated system. That could increase the trust of stakeholders and therefore the long-term sustainability of company. Corporate governance is shown to be important, along with how a committee-based decision process is needed.

Source: authors own.

The following modifications were made to complete the risk management model with moral hazard (see Table 4):

Modifications for incorporating the MCM into Mutualia.

| Modification to complete the MCM | Description | Short term relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Risk map (including moral hazards) | Result of the risk identification processes. Risk analysis and assessment. Identification and appraisal of the control mechanisms applied to activities where potential moral hazard has been identified and must therefore be managed, beyond legal and ethical compliance by the persons responsible for said activities. This covers the entire process, from inherent to residual risk. | Very high |

| Training | An ethical management training plan was drawn up to boost knowledge of the new responsible business approach, promoting employees’ career development, moral conduct and decision-making skills. | High |

| Decision-making | Establishment of protocols or procedures that underpin staff training processes, including a procedure for managing ethical dilemmas that may appear when making decisions. | Very high |

| Ethics commission | The commission's action scope will include the promotion of good corporate governance, an ethical corporate culture, as well as resolving ethical dilemmas that may occur when making decisions. It will also act as a supervisory body, with the capacity to take initiatives and exert control, supervising operations and compliance with the moral hazard plan in the field of ethical management. | Very high |

| Detection measures | Creation of procedures to assess the efficiency of the control measures imposed:

| Medium |

| Reaction to riskMeasures must be applied in the event that any changes are detected (appearance of a moral hazard) | This includes the creation of a disciplinary system that rewards / sanctions compliance or non-compliance with the measures included in the model, associated with the collective labour agreement, in turn linked to the training programme that will contribute to employee performance in line with the company's values. | Medium |

Personal interviews: descriptive variables.

| Interviewed | Date 1st Interview | Position | Departament | Age Rang | Training | Number of employees at your charge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E1NLE | 13/02/2019 | Managing Director | Management | 50–55 | Degree in Economic and Business Sciences from the UPV/EHU | 650 |

| E2JAR | 14/02/2019 | Director of Operations and Administrative Services | Management | 45–50 | Business Administration and Marketing. EMBA Deusto Business School. | 8 |

| E3DBA | 14/02/2019 | Process Director Cessation Activity | Financial benefits and Collection | 45–50 | Industrial technical engineering | 2 |

| E4LAC | 11/02/2019 | Director of Resource Management | Purchasing, Contracting and Building Management | 35–40 | Degree in Economic Law | 22 |

| E5ICS | 13/02/2019 | Management Director | Management | 40–45 | 35 | |

| E6RMV | 13/02/2019 | HR Director | HR | 60–65 | Degree in Law | 4 |

| E7LCC | 13/02/2019 | Madrid Management Director | Management | 45–50 | Degree in Law | 2 |

| E8VHU | 15/02/2019 | Organization and Quality Director | Organization and risk management | 45–50 | Bachelor of Business Sciences | 5 |

| E9MAU | 11/02/2019 | Assurance Director | Head of the Health Management Unit | 50–55 | Doctor of medicine and surgery | – |

| E10LGE | 19/02/2019 | Economic-Financial Director | Economic-Financial | 40–45 | Bachelor of Business Sciences | 25 |

| E11MLO | 17/02/2019 | Legal Affairs Director | Management | 65 | Law and Social Graduate | – |

| E12VES | 15/02/2019 | Director of Internal Audit | Internal audit | 40–45 | Bachelor of Economics | 2 |

| E13SCM | 14/02/2019 | Director of Legal Advice and Corporate Compliance | Legal Advice and Corporate Compliance | 55–60 | Law Degree | 22 |

| E14IGO | 12/02/2019 | Director of Collection and Benefits | Financial benefits and Collection | 55–60 | Geography and History | 50 |

| E15JVC | Director of communication | Communication area | 45–50 | Economic and Business | 5 | |

| E16JFO | 11/02/2019 | Guipúzcoa Healthcare Director and Head of the Department of Traumatology and Orthopaedic Surgery. | Guipúzcoa Healthcare Office | 55–60 | Doctor in medicine | 162 |

| E17VEC | 07/02/2019 | Director of Healthcare Services and Financial Benefits | Management | 55–60 | Doctor of medicine and surgery | 300 |

| E18MFM | 23/02/2019 | People Development Director | People Development | Law degree | 8 | |

| E19IIA | 15/02/2019 | Director of Information Systems | Information systems | 45–50 | Computer engineer | 19 |

| E20JOL | 14/02/2019 | Care director | Alava and Madrid health area | 55–60 | Bachelor of Medicine and Surgery | 80 |

| E21JRU | 13/02/2019 | Care Director | Bizkaia | 55–60 | Graduate in medicine and surgery. Family Medicine Specialist | 207 |

Phase 5: Specific learning after implement MCM in the organization.

Applying the MCM has been a social challenge for the management team, who considers that it has improved their ethical leadership skills. Their ongoing support and commitment are vital, as the model requires the participation of all functional areas. In the case of Mutualia, selecting the project team (21 senior managers) proved crucial for the successful results obtained, as they were dependent on the involvement of those key decision-makers within the organisation, as well as those members responsible for identifying and handling risks. Furthermore, the introduction of the new moral hazard concept and its specific characteristics require awareness-raising and training actions.

The identification of risks, which were initially considered to be moral, yet which were classified as legal following a second test (focus groups), has led the organisation to consider the need to boost legal-training skills, given the specific nature of the sector Mutualia operates in.

The findings show that it is possible to include this type of risk in monitoring, assessment and control procedures. Those actions are shown to be an essential part of managing ongoing improvements for a more moral society and to complete both the legal and moral compliance of the company. Furthermore, introducing the MCM in Mutualia has allowed the organisation to extend the scope of its objectives beyond annual financial results and incorporate moral learning processes, a major social challenge that will also enhance its sustainability strategy.

6ConclusionsThe MCM described in this article was formulated in accordance with the underlying logic of Governance, Risk management, and Compliance systems, and the specific inclusion of moral hazard control and management.

Our findings show that it is possible to introduce the MCM, based on a single case study methodology, the five phases of experimental action research and combined with PDCA (Plan, Do, Check, Action). The results indicate minor organisational changes will allow for the integration of moral hazard management with other risks.

From a theoretical perspective, the proposed model is contingent in that the expected outcomes are in line with the organisation's philosophy, actions and decisions. It does not assume or dictate the management team's behaviour; nor does it consider the results to be either desirable or unacceptable; instead, it provides a framework for reflection on the risks associated with certain forms of behaviour within the organisation that may impact negatively on third parties. It is therefore a management tool that facilitates reflection on the ethical implications of business decisions.

The concept of Governance, Risk management and Compliance (GCR) is enriched by specifically incorporating moral hazard management and overcoming legal or criminal compliance, since the proposed management of moral hazard is based on behaviour that may be incorrect from a moral point of view, but it cannot be sanctioned according to current legislation. Thus, the perspective of risk management with the MCM is broadened from the legal to the moral. A comprehensive Compliance model can help to unite the culture of the organization by integrating Legal Compliance and Moral Compliance.

This methodology has major implications for business projects when defining their goals, assuming responsibility over their stakeholders and generating moral management culture, in terms of how their actions affect third parties. Moreover, during the meetings to discuss the MCM project's goals and progress, Mutualia's board of directors agreed that introducing ethical considerations into moral hazard management decisions contributes to the company's sustainability; since the ethical decision options related to moral hazard are reduced. Mutualia has improved its decision-making processes when a person is faced with a moral dilemma by restoring to the Ethics Committee and applying a decision process relying on the ethical dilemma management tool. As Dean and Sharfman (1996) indicate, decision-making processes are related to the success of decisions. According to management, managing stakeholders’ interests beyond economic and legal aspects (compliance) is a means of adding value to the society they operate in and a lever for improving the company's standing.

Implementing the MCM model allows Mutualia to manage the underlying causes that give rise to moral hazard situations, either by controlling the decision-making process to avoid risks or by establishing specific training to improve the ethical competencies of the people involved. Regarding decision making, it has been verified at Mutualia by means of an ethical management training action of the Management Committee.

The project has two main limitations. The first is that it only considers a single case. Although the results indicate that the model can be applied to other similar organisations, this would first require further analyses and tests in order guarantee its suitability. This leads us to the second limitation, namely the need to quantify its contribution to sustainability in terms of not only the economic and financial results, but also the social ones.

Future lines of research will centre on extending the generalised use of the model and its application to other types of organisations, as well as quantifying the improvements obtained. This will require an assessment process to be conducted no sooner than one year after the introduction of the system. Another additional line of study would be to identify the most frequent moral hazards, as this would contribute to reducing their negative impact. A further area of major interest would be to study whether this model is applicable in other countries where attitudes to third party moral hazards vary.

FundingThis research has developed using the funds of UPV/EHU and the Projects titled US20/11 AND PES20/10 (GEAccounting, Lantegibatuak & UPV/EHU).

We want to thank Jose Luis Retolaza and ECRI Research Group at University of the Basque Country for their suggestions and support, but also the Mutualia team, especially its Executive Director. Also, the two reviewers and editor of the journal for their meaningful comments.