To analyze the pregnancy, live birth, and miscarriage rates of the IVF/ICSI cycles in women with low levels of AMH, compared to patients with normal levels of this hormone.

MethodsWe carried out an observational and retrospective study with the data of the patients treated in 2017 and 2018 in the Assisted Reproduction Section of La Paz University Hospital (LPHU), comparing 223 low responder patients (AMH<0.5 ng/ml and AMH 0.5–1,1 ng/ml) with 408 from the control group of normo-responder patients (AMH 1.1–3 ng/ml). Chi-square and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used.

ResultsPregnancy rate was lower in the AMH<0.5 group(14.5%), compared to the control group (35.5%) (p=0.014). No significant differences were observed comparing abortion rate and live birth rate between the study groups. At an older age, the pregnancy rate and live birth rate decreased significantly (p = 0.007 and p = 0.019). At lower levels of AMH, the number of expected and obtained oocytes, mature oocytes, and total embryos were also smaller, there were a higher rate of blank punctures and a lower rate of vitrified embryos.

ConclusionPatients with low ovarian reserve have a lower pregnancy rate compared to patients with a normal ovarian reserve. AMH plays a key role as an ovarian response marker in IVF cycles, although age is one of the factors that should be considered.

Analizar las tasas de embarazo, recién nacido vivo y aborto de los ciclos de FIV-ICSI en mujeres con bajos niveles de AMH, comparados con pacientes con niveles normales de dicha hormona.

MétodosSe llevó a cabo un estudio observacional retrospectivo con los datos de las pacientes tratadas en el Servicio de Reproducción Asistida del Hospital Universitario La Paz (HULP), comparando 223 pacientes bajas respondedoras (AMH<0,5 ng/ml y AMH 0,5-1,1 ng/ml) con 408 del grupo control de pacientes normo -respondedoras (AMH 1,1-3 ng/ml). Los análisis estadísticos se realizaron mediante Chi cuadrado y Kurskal-Wallis.

ResultadosLa tasa de embarazo fue menor en el grupo de AMH<0.5 (14.5%), comparado con el grupo control (35.5%) (p=0,014). No se encontraron diferencias significativas cuando se compararon las tasas de aborto y recién nacido vivo entre los grupos de estudio. A mayor edad, la tasa de embarazo y recién nacido vivo disminuye significativamente (p = 0.007 y p = 0.019). A menores niveles de AMH, el número de ovocitos esperados y obtenidos, de ovocitos maduros y embriones totales fue también menor, hubo una tasa mayor de punciones en blanco y menores tasas de embriones vitrificados.

ConclusiónLas pacientes con baja reserve ovárica presentan menores tasas de embarazo comparadas con pacientes con una reserve ovárica normal. Los niveles de AMH juegan un papel fundamental como marcador en los ciclos de FIV, si bien la edad, también es uno de los factores a tener en cuenta.

One of the main challenges in the field of reproductive medicine is related to patients known as poor responders to ovarian stimulation. It has been estimated that 9–24% of patients who go through IVF belong to this category (Venetis et al., 2010), and it is noted as well an increase in this number due to delayed maternity and the search for pregnancy in women of advanced age. The retrieval of a low number of oocytes means one of the limiting factors to improve live birth rates.

The definition of poor responder was standardized for the first time in 2011 by The European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) according to Bologna criteria (Ferraretti et al., 2011), so that at least two of the following must be fulfilled: advanced maternal age (>40 years) or any other risk factor of low response (ovarian endometriosis, ovarian surgery), poor ovarian response in a previous treatment (retrieval of ≤3 oocytes with a conventional stimulation protocol) and or abnormal ovarian reserve test results (antral follicle count (AFC) by ultrasound <5 or Antimüllerian hormone (AMH) <0.5–1.1 ng/ml).

However, the use of Bologna criteria results in the selection of heterogeneous groups between different studies, making it difficult to unify clinical recommendations for specialized treatment (Papathanasiou, 2014). Thus, in 2016 the POSEIDON group (Patient-Oriented Strategies Encompassing Individualized Oocyte Number) proposed a new definition for low response or low reserve patients, stratifying them into four groups depending on age (<35 or ≥35 years), AFC (<5 or ≥5), or AMH (<1.2 ng/ml) and the ovarian response, provided that there has been a previous stimulation (Alviggi et al., 2016).

Regarding ovarian reserve markers, serum FSH measurement has traditionally been used, considering levels up to 12 mUI/ml as a low response predictor (Broekmans et al., 2006). However, serum FSH levels just increase when the ovarian reserve is severely diminished (La Marca et al., 2012). For this reason, antimüllerian hormone and antral follicle count are the most recent markers. AMH is a glycoprotein secreted by granulosa cells of antral and preantral ovarian follicles. AFC is performed by ultrasound, counting the identifiable antral follicles from 2 to 10 mm in both ovaries. Both markers show a high correlation with ovarian reserve (Baker et al., 2018; Fleming et al., 2015). For its part, AMH supposes an advantage due to its low inter-and intra-cycle variability, which turns it into a very useful marker in clinical practice.

According to the evidence previously presented, it seems interesting to determine with the information achieved from new studies the relevance of antimüllerian hormone as an ovarian reserve marker and its role as a predictor of pregnancy, as well as the possible age moderating effect on patients considered as poor responders.

ObjectivesThe primary objective of this study is to analyze the pregnancy, live birth, and miscarriage rates of the IVF/ICSI cycles that were carried out between 2017 and 2018 in La Paz University Hospital (HULP) in women with low levels of AMH, compared to patients with normal levels of this hormone, taking into account not only the AMH level but the age of the patient and the number of previous cycles performed.

Secondary objectives: to analyze, according to the AMH, the age of the patients, the indications of assisted reproductive technology (ART) (male sterility, failure of artificial insemination of husband's semen (IAC), diagnosis of low ovarian response, tubal factor, endometriosis, repeated abortions, sterility of unknown origin), the percentage variation of oocytes, the rate of blank punctures, the percentage of immature oocytes obtained, number of embryos generated and vitrified, and their quality.

Material and methodsWe carried out an observational, analytical, and retrospective study with the anonymized data of the patients treated in 2017 and 2018 in the Assisted Reproduction Section of the HULP. Data from 912 cycles were collected, including as such the process of ovarian stimulation, follicular puncture, IVF or ICSI, vitrification of embryos and/or transfers of embryos, as well as the diagnosis of pregnancy or abortion.

We included 631 of the 912 cycles recorded, corresponding to those of the low responding patients and the control group. All patients with AMH greater than or equal to 3 ng/ml were excluded from the study, because it may imply a high response to ART cycles in this subgroup of patients. Low responders were defined as patients with AMH less than 1.1 ng/ml, and they were subdivided into two groups: AMH <0.5 ng/ml and AMH> 0.5 ng/ml and <1, 1 ng/ml. The control group is formed with normo-responding patients, whose AMH was set between 1.1 and 3 ng/ml. Smokers were not excluded, and they were represented both in the study and the control group.

The medical records of the patients were reviewed both at the HULP Clinical Station and the HCIS program. The collected data were age, the cycle of ART in which the patients were, the indication of ART (male sterility, IAC failure, low ovarian response, polycystic ovary syndrome, endometriosis, ovodonation, tubal factor, uterine factor, and abortion repetition), the levels of AMH, the levels of the beta subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) with which the presence or not of pregnancy was determined, and the follow-up of pregnancy until delivery or abortion.

For the ovarian stimulation, we used GnRH-antagonists stimulation protocols based on recombinant FSH and both FSH and LH. It was used an in vitro immunological test for the quantitative determination of anti-mullerian hormone (AMH) in human serum and plasma by means of the "ECLIA" electrochemiluminescence immunoassay. Serum AMH (ng/ml) levels were measured by endo-pnt-000012 cobas e_601 system.

Data from the embryology laboratory were collected in the SARAplus software application. We included the number of expected oocytes, based on the folliculometry performed by ultrasound scan, the number of oocytes in metaphase II obtained after a puncture, the percentage variation of oocytes (number of oocytes obtained/number of expected oocytes), the number of oocytes matures and immature and their percentage, number of blank punctures (without any aspirated oocytes), number of badly fertilized embryos (3 pronuclei), number of well-fertilized embryos (2 pronuclei) and their quality (good quality, embryos A and B, poor quality embryos C and D according to the ASEBIR criteria), and the vitrification rate.

With these data, a statistical study was carried out using the IBM SPSS Statistics 23 program. First of all, the variables were codified: age was divided into three ranges: <35 years, between 35 and 38 years and >38 years; and the AMH in four ranges: <0.5 ng/ml, between 0.5 and 1.1 ng/ml, between 1.1 and 3 ng/ml and >3 ng/ml. We used the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test to study the normality of the distributions of the variables.

Quantitative variables were expressed by means (x¯) and standard deviation (σ), compared with the Kruskal–Wallis test. Qualitative variables were described with percentages and were compared with the chi-square test and linear by linear association. Likewise, logistic regression was used to study the objective variables.

Results were considered statistically significant when p <0.05.

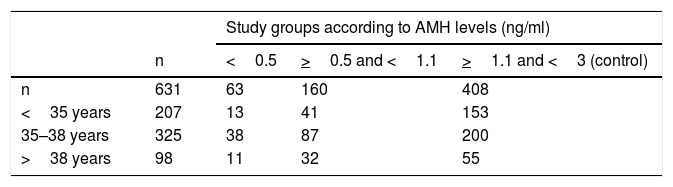

ResultsData of the 631 cycles of IVF/ICSI carried out between the years 2017 and 2018 in HULP in patients with AMH <3 ng/ml have been included. Table 1 shows the distribution of patients in each study group according to their age and AMH. AMH mean was 1.44 ng/ml with a standard deviation of 0.72, a minimum of 0, and a maximum of 2.98.

Patients had a mean age of 35.52 years with a standard deviation of 3.07, a minimum of 24, and a maximum of 41; in the AMH group <0.5 mg/ml the mean was 36.17 + 2.23 years, in the 0.5 to <1.1 ng/ml (35.98 + 2.98 years) and in the control (35.18 + 3.20 years).

When the distribution of patients according to their age is analyzed within each AMH group, we observe differences in the range of women under 35 years old. In the group of AMH <0.5 ng/ml, the youngest ones represent 21% of the total of patients, 26% in the group of AMH 0.5–1.1 ng/ml, and 37.5% in the control group. Patients younger than 35 years have a higher prevalence in the control group, compared to the group with low ovarian reserve (BRO). This does not happen in other age ranges.

At the time of the study, 53.7% of the patients were in the first treatment cycle, 31.3% in the second, and 15% in the third or more.

Looking at indications for treatment, we found that in 309 patients the indication was due to male factor, 229 low ovarian reserve, 136 failure of IAC, 122 endometriosis, 88 tubal factor, 11 uterine factor, 5 polycystic ovary syndrome, 5 with donation, 4 sterility of unknown origin, and 3 for repeated abortions. When we study these indications according to the level of AMH, a significant relationship was found between failure of IAC and low ovarian response (LOR). The higher the AMH, the greater the failure in IAC (when AMH <0.5: 6.5%, when AMH 0.5–1.1: 18.8%, and when AMH 1.1–3: 26.7%), with a p = 0.001. The lower the AMH, the greater the indication of treatment due to low response (when AMH <0.5: 74.2%, when AMH 0.5–1.1: 63.6%, and when AMH 1.1–3: 22, 2%), with a p <0.001.

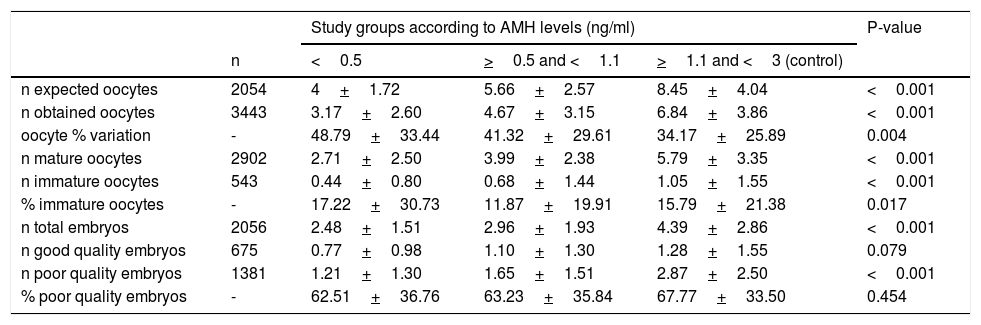

Regarding the variables related to the embryology laboratory (Table 2), in the study group, the number of expected and obtained oocytes was significantly lower, with a greater percentage variation. The number of mature oocytes and total embryos was also smaller. The number of good-quality embryos did not reach statistical significance.

Description and comparison of embryology laboratory variables.

| Study groups according to AMH levels (ng/ml) | P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | <0.5 | >0.5 and <1.1 | >1.1 and <3 (control) | ||

| n expected oocytes | 2054 | 4+1.72 | 5.66+2.57 | 8.45+4.04 | <0.001 |

| n obtained oocytes | 3443 | 3.17+2.60 | 4.67+3.15 | 6.84+3.86 | <0.001 |

| oocyte % variation | - | 48.79+33.44 | 41.32+29.61 | 34.17+25.89 | 0.004 |

| n mature oocytes | 2902 | 2.71+2.50 | 3.99+2.38 | 5.79+3.35 | <0.001 |

| n immature oocytes | 543 | 0.44+0.80 | 0.68+1.44 | 1.05+1.55 | <0.001 |

| % immature oocytes | - | 17.22+30.73 | 11.87+19.91 | 15.79+21.38 | 0.017 |

| n total embryos | 2056 | 2.48+1.51 | 2.96+1.93 | 4.39+2.86 | <0.001 |

| n good quality embryos | 675 | 0.77+0.98 | 1.10+1.30 | 1.28+1.55 | 0.079 |

| n poor quality embryos | 1381 | 1.21+1.30 | 1.65+1.51 | 2.87+2.50 | <0.001 |

| % poor quality embryos | - | 62.51+36.76 | 63.23+35.84 | 67.77+33.50 | 0.454 |

Note: Kruskal–Wallis test, Mean + standard deviation

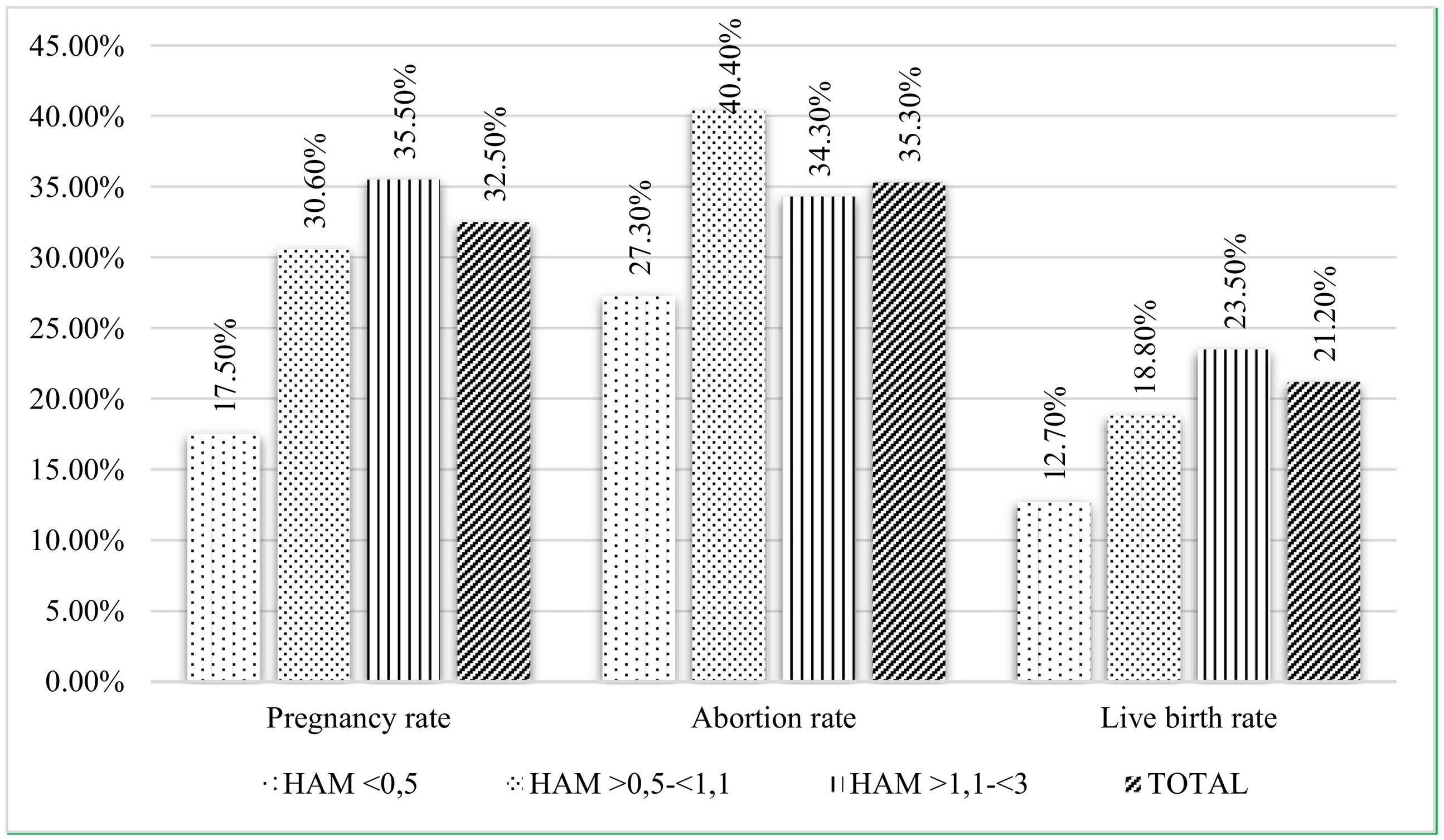

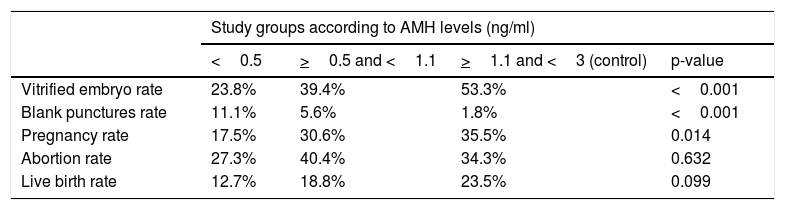

On one hand, at lower levels of AMH, there were a higher rate of blank punctures and a lower rate of vitrified embryos (Table 3). Regarding pregnancy, the overall rate reached 32.5%, with significant differences in favor of the control group when comparing to the AMH<0.5 group. The overall abortion rate was 35.3% and the overall live birth rate was 21.2%. When comparing both variables between the study groups, no significant differences were observed, although there is a tendency of linear rise as the AMH increases for the rate of live birth (Fig. 1).

Comparison of percentages of vitrified embryo rate with the rate of blank punctures, the rate of pregnancy, abortion and live birth rate within the AMH group.

| Study groups according to AMH levels (ng/ml) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <0.5 | >0.5 and <1.1 | >1.1 and <3 (control) | p-value | |

| Vitrified embryo rate | 23.8% | 39.4% | 53.3% | <0.001 |

| Blank punctures rate | 11.1% | 5.6% | 1.8% | <0.001 |

| Pregnancy rate | 17.5% | 30.6% | 35.5% | 0.014 |

| Abortion rate | 27.3% | 40.4% | 34.3% | 0.632 |

| Live birth rate | 12.7% | 18.8% | 23.5% | 0.099 |

Note: Chi-square

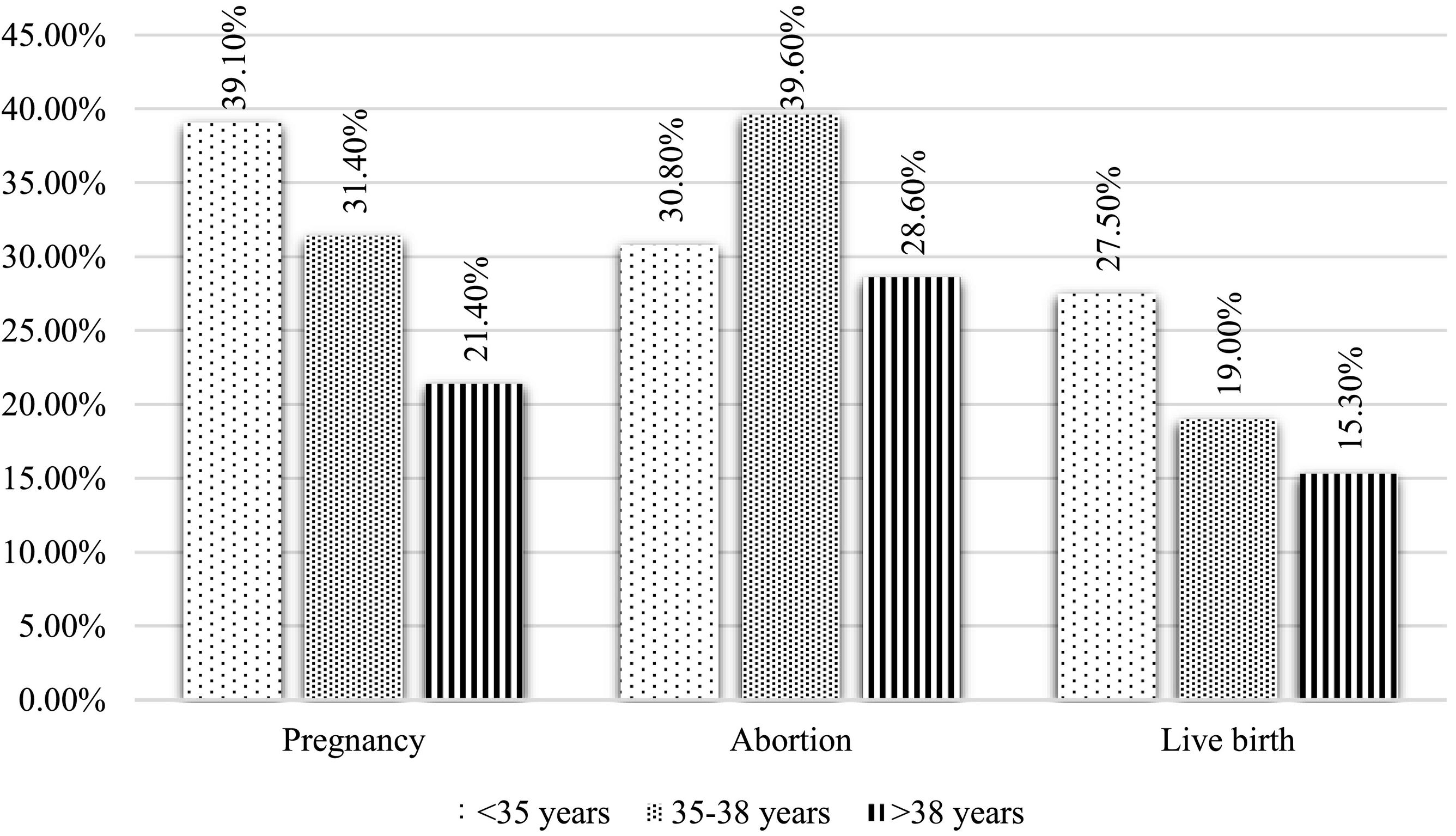

On the other hand, the relationship between age and pregnancy, abortion, and live birth rates were also studied (Fig. 2). At an older age, the pregnancy rate and live birth decreased significantly (p = 0.007 and p = 0.019, respectively). However, there were no differences found regarding the abortion rate. Nor did they show significant differences when comparing pregnancy, abortion, and live birth rates according to the number of treatment cycle in which the patients were. The pregnancy rate was 32.3% in the first cycle, 32.8% in the second cycle, and 28.1% in the third cycle or higher (p = 0.71). The abortion rate was: 33.3% in the first cycle, 41% in the second cycle, and 32% in the third cycle (p = 0.568). The RNV rate in the first cycle was 20.1%, 19.4% in the second cycle, and 24.7% in the third cycle (p = 0.561).

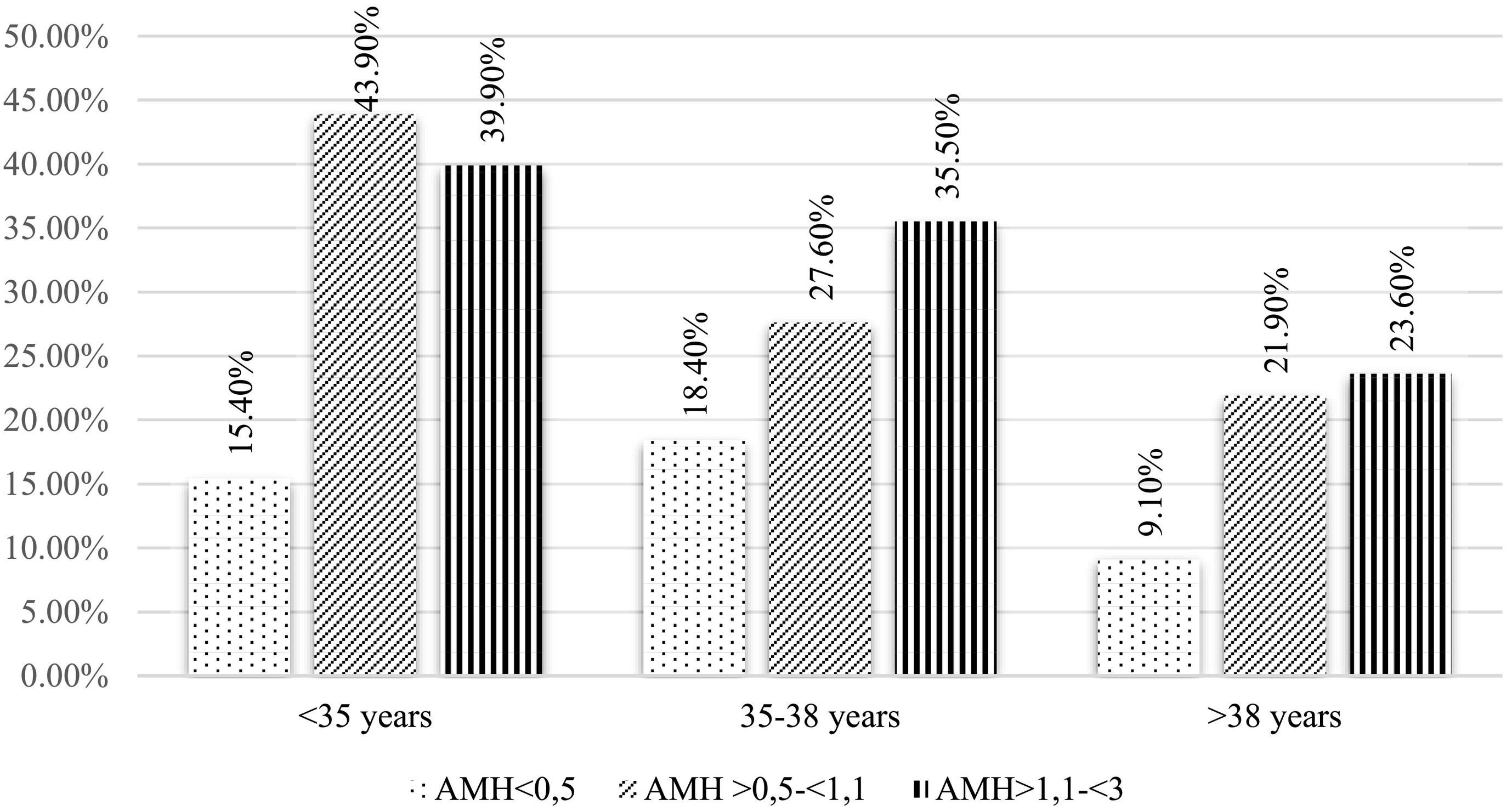

A logistic regression analysis was carried out to determine the relationship between the levels of AMH and the pregnancy rate according to age (Fig. 3). In this scenario, the pregnancy rate in the control group versus the AMH <0.5 ng/ml group (p = 0.001) remains significantly higher, as shown in Fig. 3. Besides, comparing by age ranges, there are differences between the group <35 years and the group of >38, being the highest pregnancy rate in the youngest (p=0.01). Regarding abortion and live birth rates, through logistic regression, combining age and AMH, no statistically significant differences were observed.

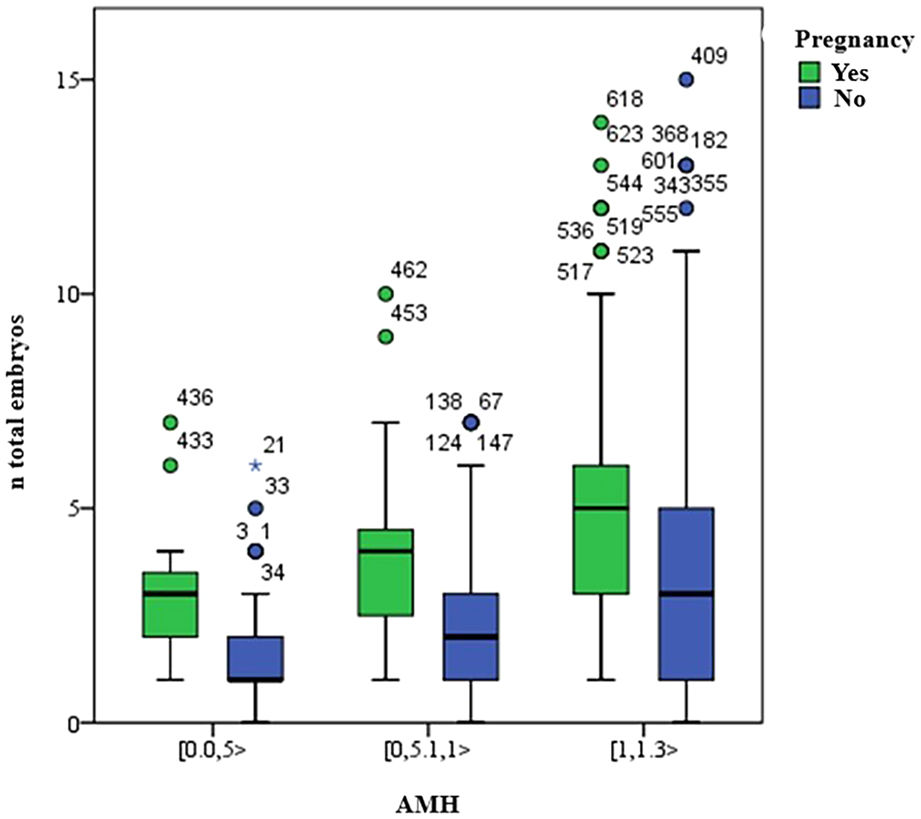

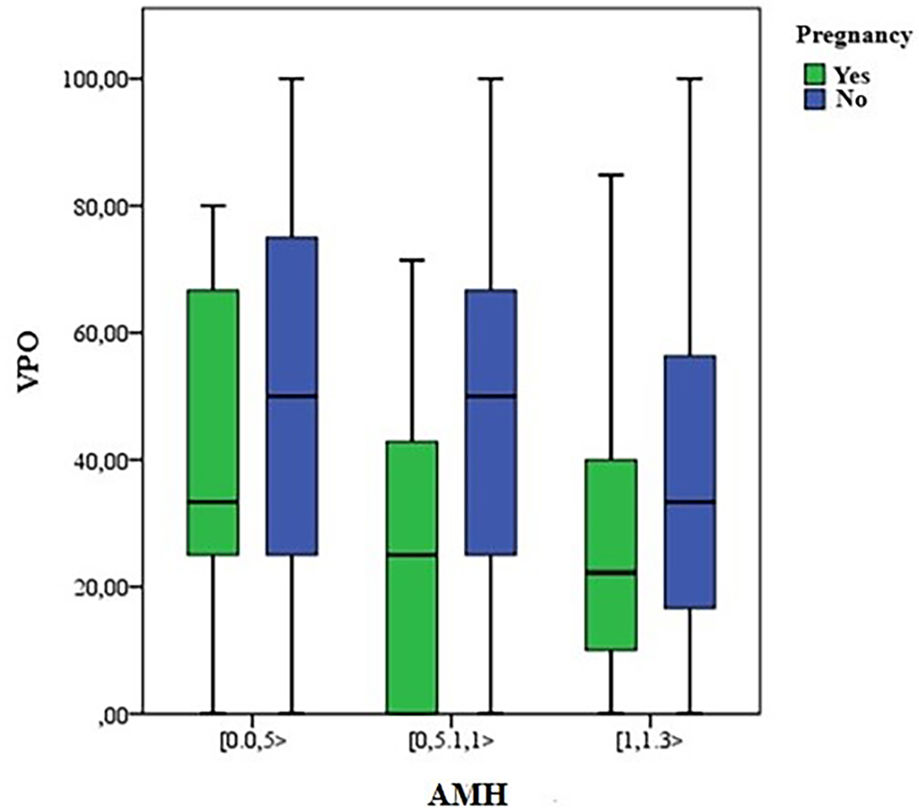

Finally, the total number of embryos and the percentual variation of oocytes (VPO), as described and compared in Table 1, were associated with the presence or not of pregnancy (Figs. 4 and 5). There were more pregnancies in those with a higher number of embryos, with higher levels of AMH, as well as in those patients with a lower percentual variation of oocytes (VPO).

The main objective of this study was to analyze the pregnancy, live birth, and miscarriage rates of the IVF/ICSI in women with low levels of AMH. Our results determine that these patients have a lower pregnancy rate compared to patients with a normal ovarian reserve, a situation that is maintained when we adjust the data according to the age of the patients. In line with these results, different studies have led to similar conclusions (Bozdag et al., 2017; Malchau et al., 2018; Yakin et al., 2018). However, unlike those studies, it has not been possible to demonstrate the relationship with lower RNV rates in our work (Alson et al., 2018; Brodin et al., 2013). There is a linear trend, but it does not reach statistical significance, as can be seen in the description of the results in Table 3.

The reason why patients with low ovarian reserve achieve lower pregnancy rates lies in the poor response they present to pharmacological ovarian stimulation. It has been demonstrated that in women with lower levels of AMH the number of oocytes recovered after a puncture is lower than in women with a normal ovarian reserve. Women with lower levels also present a greater percentual variation than the number of oocytes expected according to the previous follicometry. In these patients, there is a greater proportion of blank punctures, as well as immature oocytes. By achieving a smaller number than available oocytes, the amount of embryos is equally lower in this type of patient, as previous studies pointed out (La Marca et al., 2009). With fewer embryos, the vitrification rate was also lower compared to the group with good ovarian reserve.

If the results achieved are adjusted taking age into account, the pregnancy rate remains lower in the LOR group compared to the control group. However, there are significant differences in favor of younger patients when compared with those older than 38 years. The negative correlation between age and fertility is well known (González-Foruria et al., 2016; Su et al., 2017; Sunkara et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2018), not only because of the decrease in the number of oocytes but also for the quality worsening of them.

Looking at the abortion rate, no significant differences were found between the different study groups. It does not happen the same in other works such as Haadsma et al. (2010), where they describe a significantly higher abortion rate in women with low response over 36 years than those of normoresponders, but not in younger patients, once again showing the influence of age on oocyte quality.

It is established that the antimüllerian hormone levels, due to their relationship with the growth of the antral follicles, represent a good marker of low ovarian response (Capecce et al., 2016). For this reason, in this study, we have selected as low responding patients those with lower AMH than 1.1 ng/dl. However, the FAC and the age of the patients could have been also included as in the Bologna criteria (Ferraretti et al., 2011). However, there were only 33 patients with more than 40 years, due to the public health limit of 40 years to access assisted reproduction treatments.

Although AMH has an important role as a marker for ovarian reserve and therefore pregnancy after an IVF cycle, age is the most important factor when determining the success of assisted reproduction treatment (Goswami and Nikolaou, 2017). In our study, within the group of patients with low ovarian reserve, the overall pregnancy rate in those under 35 years was 59%, compared to 31% in those over 38 years, findings that are in line with the conclusions established in other studies (Sefrioui et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2016).

Therefore, stratifying the patient with low ovarian reserve according to their age is key when we are trying to predict the success of treatment. It is important to unify the criteria that define patients with low response, to create homogeneous study groups that allow us to establish a more accurate prognosis and use treatment guidelines in a more appropriate way for each patient.

Among the limitations of this study, and even when the findings coincide with the main conclusions of previous studies, it would be interesting to achieve bigger homogeneity between the analysis groups. In our case, there were a total of 223 low responders compared to 408 normoresponders.

Likewise, part of the patients studied had not yet been transferred or was still pregnant, and the rates of pregnancy, abortion, and live birth could therefore vary.

It is also important to notice that, since the variables did not follow normality, we had to use non-parametric tests in statistics and it was not possible to draw the significance value between each group, but only between the three of them as a whole.

ConclusionIn line with the main objective, the results support that patients with low ovarian reserve, defined by AMH levels less than 1.1 ng/dl, have a lower pregnancy rate compared to patients with a normal ovarian reserve. Besides, this situation is maintained when we adjust the data according to the age of the patients. There are no differences, however, in abortion and newborn rates, although a tendency has been observed suggesting that the higher the AMH the rate of live birth also increases.

Regarding age, pregnancy, and live birth rates decrease as it increases, not observing these differences in abortion rates. Regarding the ART cycle, no relationship has been found with pregnancy, abortion, and live birth rates. In low responders, the number of expected follicles is lower than in normoresponding patients, a smaller number of oocytes is obtained and the number of embryos generated is equally lower, associating this low number of embryos with a lower pregnancy rate

AMH plays a key role as an ovarian response marker in IVF cycles, especially from a quantitative point of view, although age, due to its involvement in oocyte quality, is also one of the factors that should be taken into account.

Disclosure statementNo potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Details of ethics approvalEthical approval was not required.

Contribution to authorshipAll authors were involved in the study. OA was in charge of the conception and planning of the study. Clinical study data analysis was undertaken by SV. The manuscript was written by BAL, with assistance from EG, SI, and AH. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

FundingNone.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare no conflict of interest.