Episodic ataxia is characterised by recurrent episodes of poor coordination and balance; the incidence of the condition is below 1 case per 100 000 population.1 Despite its characteristic clinical features, diagnosis may be delayed due to the association with other interictal symptoms and such other episodic neurological disorders as epilepsy, paroxysmal dyskinesia, and migraine.2

We present the case of a 46-year-old man with history of arterial hypertension and dyslipidaemia who reported episodes of dysarthria and instability of several hours’ duration. He had no family history of interest. His parents were non-consanguineous. He was the oldest of 4 siblings (3 sisters, aged 30, 31, and 35) and had a 4-year-old son. He had received antiepileptic treatment during childhood due to episodes of loss of consciousness. He also presented episodic, migraine-like headache. Twenty days previously, our patient had been admitted to another hospital during one of the episodes. Head and neck MRI, EMG, and a blood analysis including autoimmunity and serology testing all yielded normal results. He was asymptomatic at discharge, and no diagnosis was established. According to our patient, the frequency of episodes varied (from several episodes per day to no episodes for several weeks), but increased with stress or tiredness. He also reported progressive gait deterioration between episodes.

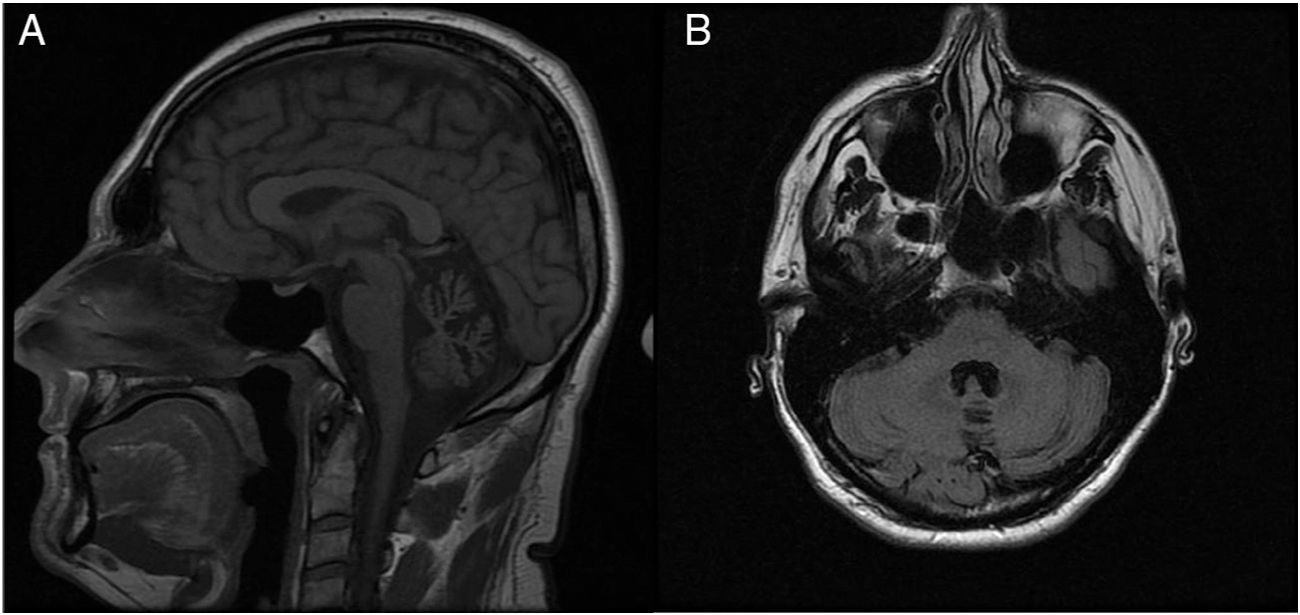

A neurological examination performed between episodes revealed persistent multidirectional horizontal nystagmus, mild dysarthria, and bilateral dysmetria (finger-to-nose test). A genetic study of spinocerebellar ataxia, requested previously, yielded negative results for ATXN2 (spinocerebellar ataxia type 2) and ATXN3 (spinocerebellar ataxia type 3) mutations. The brain MR image, initially reported as normal, revealed atrophy of the cerebellar vermis (Fig. 1).

Due to the chronology of the episodes (self-limiting, of several hours’ duration) and the presence of nystagmus and progressive ataxia between episodes, we requested a study of the CACNA1A gene, responsible for episodic ataxia type 2; the study detected missense mutation c.889 G > A (p.Gly297Arg;Het). We prescribed acetazolamide, which reduced the frequency of episodes.

Episodic ataxia type 2 is the most frequent of the 8 subtypes of episodic ataxia described to date. It was first described in 1946,3 although its association with CACNA1A, which encodes the calcium voltage-gated channel subunit alpha1 A, was not described until 1996.4 The condition follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern5 and shows high though incomplete penetrance.6 It is known that a single CACNA1A mutation can present high phenotypic variability, causing a wide range of neurological disorders, from migraine with aura to transient focal neurological signs without headache, coma induced by mild head trauma, and slowly progressive cerebellar ataxia.7 In the case presented here, the mutation detected in our patient has only been described in a family with recurrent episodes of ataxia and mild oculomotor and cerebellar dysfunction8 and in a child with paroxysmal tonic upgaze who subsequently developed episodic ataxia, global developmental delay, and migraine.9

Although this type of ataxia is initially episodic, with physical and emotional stress being the most frequent trigger factors, up to 90% of patients will develop interictal nystagmus and 50% will display progressive ataxia.10 As in our case, patients with episodic ataxia type 2 present increased risk of epilepsy, and approximately 50% develop episodic migraine. Other authors have reported alterations in stimulated single-fibre EMG that improved with increased stimulation frequency; these findings are compatible with presynaptic failure of neurotransmission.11

Patients with episodic ataxia type 2 frequently display atrophy of the cerebellar vermis on brain MRI scans, particularly in cases of long progression and persistent interictal ataxia; however, in the absence of strong clinical suspicion, the condition may remain unnoticed for a long time, as in our case.

Differential diagnosis of episodic ataxia includes such peripheral nervous system disorders as peripheral vertigo (benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, Meniere disease, autoimmune inner ear disease, labyrinthitis, etc) and such central nervous system disorders as migraine, toxicity, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, Chiari malformation type I, paroxysmal dyskinesia, functional disorders, and atlantoaxial abnormalities.6 Most of these entities can be ruled out with thorough medical history taking and complementary testing. However, the main diagnostic challenge is differentiating episodic ataxia type 2 from other entities associated with CACNA1A mutations, such as familial hemiplegic migraine type 1, which is frequently associated with progressive cerebellar dysfunction that is indistinguishable from that of episodic ataxia type 2, and spinocerebellar ataxia type 6, which presents with fluctuating symptoms and responds to acetazolamide.10

Our case demonstrates the importance of considering episodic ataxia type 2 in patients with recurrent episodes of ataxia of several hours’ duration. We were surprised by the diagnostic delay of over 20 years in a patient presenting typical symptoms of episodic ataxia type 2. This may have been due to the presence of interictal nystagmus and ataxia, the lack of family history of the condition, and the patient’s history of childhood epilepsy.

FundingThe authors received no funding for this study.

Please cite this article as: Muro García I, Toribio-Díaz ME, Quintas S. Ataxia episódica: 20 años de retraso diagnóstico. Neurología. 2020;35:500–501.