With the explosive population growth an increased use of land for cultivation purposes and the usage of biotechnologies in agriculture—such as pesticides—respond to the need for more efficient systems. However, improper application of pesticides has a negative effect on the environment, on exposed animals and on humans. Cypermethrin, a synthetic pyrethroid, is an insecticide with low risk to human and animal health and with broad insecticidal activity against a large number of pests. Studies in humans and animals show morphological and functional alterations in different organs exposed to cypermethrin. Pyrethroids are chemicals with structural similarity to pyrethrins and possess increased toxicity to insects over mammals.

ObjectiveThis research analyzes the variations of the state of differentiation of Sertoli cells and androgen receptor expression in testes of healthy adult mice exposed to cypermethrin.

Material and methodMice were divided into three groups: control 1 (untreated), control 2 (inoculated intraperitoneally with 0.1ml of vegetable oil), and the experimental group 3 (inoculated with 1/5 of the lethal dose 50 (LD50=485mg/kg) of cypermethrin).

ResultsCypermethrin exerts acute and chronic effects on Sertoli cells in the testis of the adult mouse. These effects are manifested by the significant increase in epithelial height and the dedifferentiation of Sertoli cells evidenced through the presence of the Ck 8/18-type intermediate filament—a characteristic of differentiating cells—especially considering the functional cyclicity of the testicular compartment.

ConclusionsCypermethrin significantly affects the structure and function of Sertoli cells through the cytoskeleton and the state of maturation.

Con el crecimiento explosivo de la población, un mayor uso de la tierra con fines de cultivo y el uso de las biotecnologías en la agricultura—como pesticidas—responden a la necesidad de sistemas más eficientes. Sin embargo, la aplicación inadecuada de pesticidas tiene un efecto negativo sobre el medio ambiente, en los animales expuestos y en los seres humanos. La cipermetrina, un piretroide sintético, es un insecticida de bajo riesgo para la salud humana y animal, y con una amplia actividad insecticida frente a un gran número de plagas. Los estudios en seres humanos y animales muestran alteraciones morfológicas y funcionales en diferentes órganos expuestos a la cipermetrina. Los piretroides son sustancias químicas con estructura muy similar a las piretrinas, a menudo más tóxicas para insectos que para mamíferos.

ObjetivoLa presente investigación analiza las variaciones del estado de diferenciación de las células de Sertoli y de la expresión del receptor de andrógeno en testículos de ratones adultos sanos expuestos experimentalmente a cipermetrina.

Material y métodoLos animales fueron distribuidos en 3 grupos: control 1 (n= 3) sin tratamiento, control 2 (n = 15) inoculados con 0,1ml de aceite vegetal vía intraperitoneal, y el grupo 3 y experimental (n = 15) inoculados con 1/5 de la dosis letal 50 (LD50= 485mg/kg) de cipermetrina.

ResultadosSe observó que la cipermetrina tiene efectos agudos y crónicos sobre las células de Sertoli en el testículo de ratón adulto. Estos efectos se demuestran por el aumento significativo de la altura epitelial, como también por una desdiferenciación de las células de Sertoli a través de la presencia de los filamentos intermedios tipo CK8/18, característico de células en diferenciación, más aun considerando la ciclicidad funcional del compartimiento testicular.

ConclusionesLa cipermetrina afecta significativamente a la estructura y la funcionalidad de las células de Sertoli, a través del citoesqueleto y el estado de maduración.

Exposure to pesticides can have acute, chronic and long-term effects on people, animals and the environment.1 Cypermethrin is a type II pyrethroid widely used in the management of livestock and the production of primary agricultural products (cotton, cereals, vegetables and fruits), as well as a controlling agent for vectors of infectious diseases in public health.2 Research in animal models show that pyrethroids exert a significant adverse impact on organs and systems such as liver, brain, immune and reproductive systems.3–6

In the reproductive system of mice, cypermethrin decreases fertility, reduces the number of implantation sites and viable fetuses in females crossed with males previously exposed to cypermethrin,7 while in males cypermethrin significantly reduces testosterone levels by inhibiting testicular steroidogenesis, thus deteriorating the normal spermatogenesis.8

Sertoli cells (SCs) are the supporting and nourishing cells for male germ cells.9 Changes in their general and nuclear morphology might be associated with absent or weak expression of the androgen receptor (AR) during puberty.10 Testes with total absence of AR expression show alterations in their development and function. The lack of androgen receptors in Sertoli cells affects the production and secretion of testosterone in Leydig cells, as well as the normal spermatogenesis.11,12

The number of SCs determines the size of the adult testis and daily sperm production; this relationship is established because each Sertoli cell sets the number of germ cells that it can sustain. The variation of these parameters provides a clear correlation with the number of functional somatic cells.9

Once the individual reaches reproductive maturity, SCs experience a radical change in their morphology and function: from an immature proliferative (fetal) state to a non-proliferative mature (adult) state. In laboratory animals, evidence indicates an important role of thyroid hormone (T3) in the maturation of SCs. T3 interacts with androgens and perhaps FSH, and both induce the expression of androgen receptor (AR) on the Sertoli cell, making them responsive to androgens and assuming support functions during spermatogenesis.11

Ck-8/18 corresponds to a type of intermediate filament in epithelial cells, including the Sertoli cell. Human Ck-8/18 is a strong marker of cell immaturity, and in adult testis it is used to identify seminiferous tubules where Sertoli cell are immature or have changes in their differentiation process.13 When induced by experimental means (i.e. heat stress), Ck-8/18 expression is evidenced by immunohistochemistry 10 days post-induction, with a marked increase in its expression on days 15–30.14,15 It is even possible that the optimum conditions are generated entirely to start the process of Sertoli cell proliferation.16

Therefore, in this research the quality of Sertoli cells (SCs) is studied with the use of morphological and functional markers (Ck-8/18 and AR, respectively) after an experimental intoxication with cypermethrin to identify possible mechanisms of action of cypermethrin on the mouse testis.

Materials and methodsBiological and chemical materialThirty four male CF1 mice (2.5–3 months old, 28–40g body weight) were used, maintained under standard feeding conditions, with 12:12hour cycle of light and darkness in the animal facility of the University of Chile. The selected chemical material, i.e. cypermethrin, was obtained from ANASAC (92.5% (w/w) purity)5,6 and suspended in sunflower vegetable oil (Belmont, Chile). During the experimental period, animals were kept as recommended by the Bioethics Committee of the School of Medicine, University of Chile.

Experimental designAnimals were divided into the following groups: control 1 (n=4, untreated), control 2 (n=15, inoculated intraperitoneally with 0.1ml vegetable oil), and the experimental group (n=15, inoculated intraperitoneally with 1/5 of the LD50 (485mg/kg b. w.)) of cypermethrin suspended in 0.1ml vegetable oil. The testes of 3 mice from each group were extracted at 1 (including 4 animals in the control group without any treatment), 8.6, 17.2, 25.8 and 34.4 days post treatment, after euthanasia according to the protocols of the National Institute of Health17 and AVMA.18 These periods coincide with the time needed for metabolism, elimination and retention of cypermethrin in adipose tissue, with a half life of 9, 12 and 18 days, respectively.

Testis processingTestes were fixed in Bouin's alcoholic solution for 8h. Subsequently, they were embedded in paraffin (melting point 56–58°C) and subjected to standard histological techniques (fixation, dehydration in alcohols, paraffin embedding, cutting, staining/IHC and assembly). Five micron thick tissue sections (LEICA LEITZ 1512 microtome) were then mounted on silanized slides (Star Frost, USA).

Morphometric analysisAfter Mayer's hematoxylin-PAS staining, field micrographs were obtained on an OLYMPUS CX31 microscope (under 100× objective) with a digital camera and quantitative software Mshot Digital Imaging System v9.3 (Guang Zhou Micro-shot Technology Co., China), always considering three histological sections per animal. In epithelial tissues, the height of the luminal cells (epithelial height is measured from the base to the top of the tubular compartments, in micrometers) represents the intensity of their activity according to their physiological status and their association with other cells. Changes in testis from digitized images were assessed in the areas of spermatogenesis and perimeters of the seminiferous tubules (areas and perimeters were measured following the contours of the seminiferous tubules in cross sections, in micrometers). Both variables were expressed in micrometers.

ImmunohistochemistryImmunohistochemistry was carried out using specific anti-Ck 8/18 and anti-AR antibodies, according to the protocols recommended by the respective manufacturer:

- 1.

Cytokeratin 8/18 (Ck-8/18) and specific antibody (clone 5D3, Thermo Fisher Scientific Co., LabVision Cat # MS-743-R7). Sertoli cells were analyzed using specific anti-Ck-8/18 monoclonal antibodies. The evaluation was done by quantifying the number of positive Sertoli cells with cytoplasmic brown color per total seminiferous tubules (tubular index).

- 2.

Androgen receptor protein (Androgen Receptor AB-1, mouse monoclonal antibody, clone AR 44, Thermo Fisher Scientific Cat. # MS-443-B0). The evaluation was performed by quantifying the number of positive Sertoli cells with a dark brown nucleus per total seminiferous tubules (tubular index).

Both antibodies were revealed through the DAB/HRP system, which generates a dark brown precipitate after positive reaction. IHC assays were performed with three repetitions, and in each section at least 30 cross-sectional seminiferous tubules (positive cells/total tubules) were evaluated.

Statistical analysisData were analyzed in Excel 2007 worksheets (Microsoft, USA). The differences between the means for each variable among groups were analyzed by analysis of variance with post hoc tests (ANOVA, Kruskal–Wallis test and Dunn's test, considering p<0.05) using the statistical software Stat-Graph.

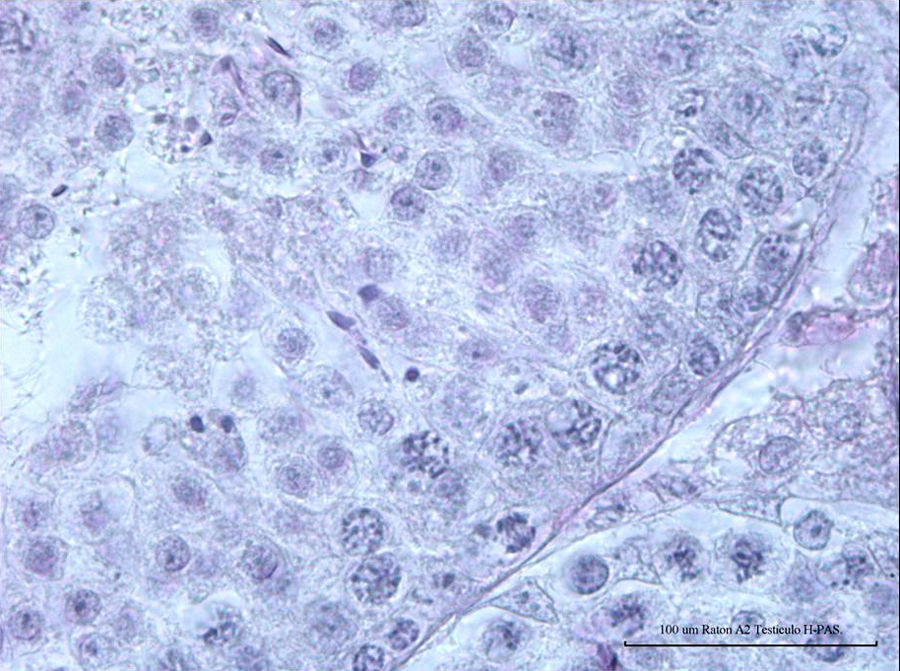

ResultsNormal spermatogenesis: control group animalsAs depicted in Fig. 1, the seminiferous tubules of adult mice possess a tubular compartment exhibiting the cell population that represents the full spermatogenic process, including the concepts of spermatogenic stages (12 stages in mouse, with specific cell associations by tubules), seminiferous epithelium cycle (length: 8.6 days) and wave (space in the seminiferous tubules for 4 cycles) in a normal mouse. Fig. 2 (animal from control group; hematoxylin–PAS staining) corresponds to a cross section of a seminiferous tubule showing a seminiferous epithelium in normal spermatogenesis process, including Sertoli cells and germline cells (spermatogonia, pachytenes, and spermatids).

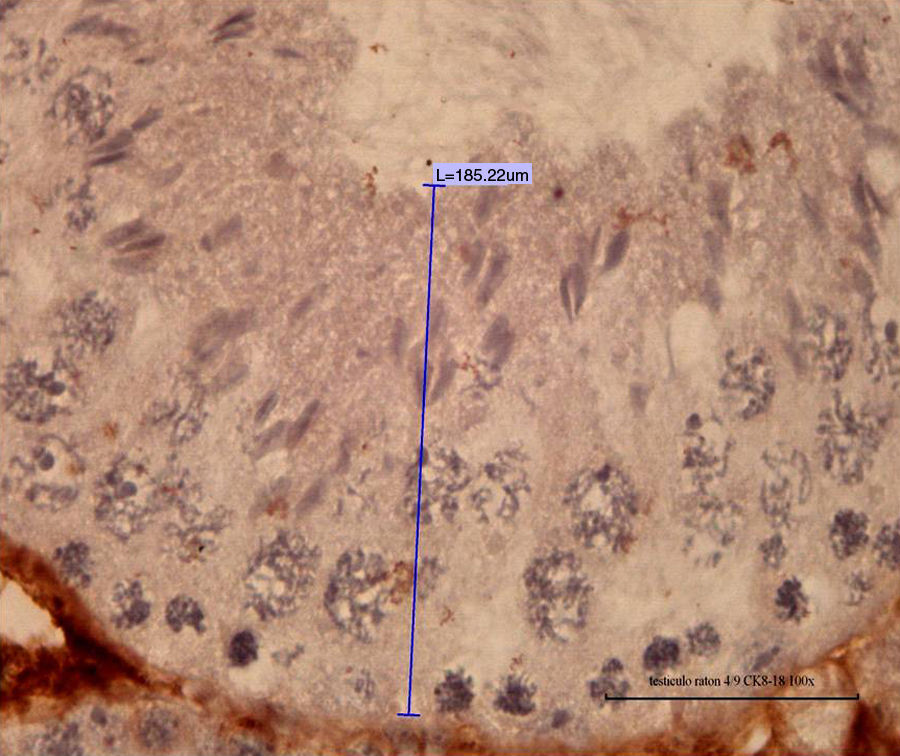

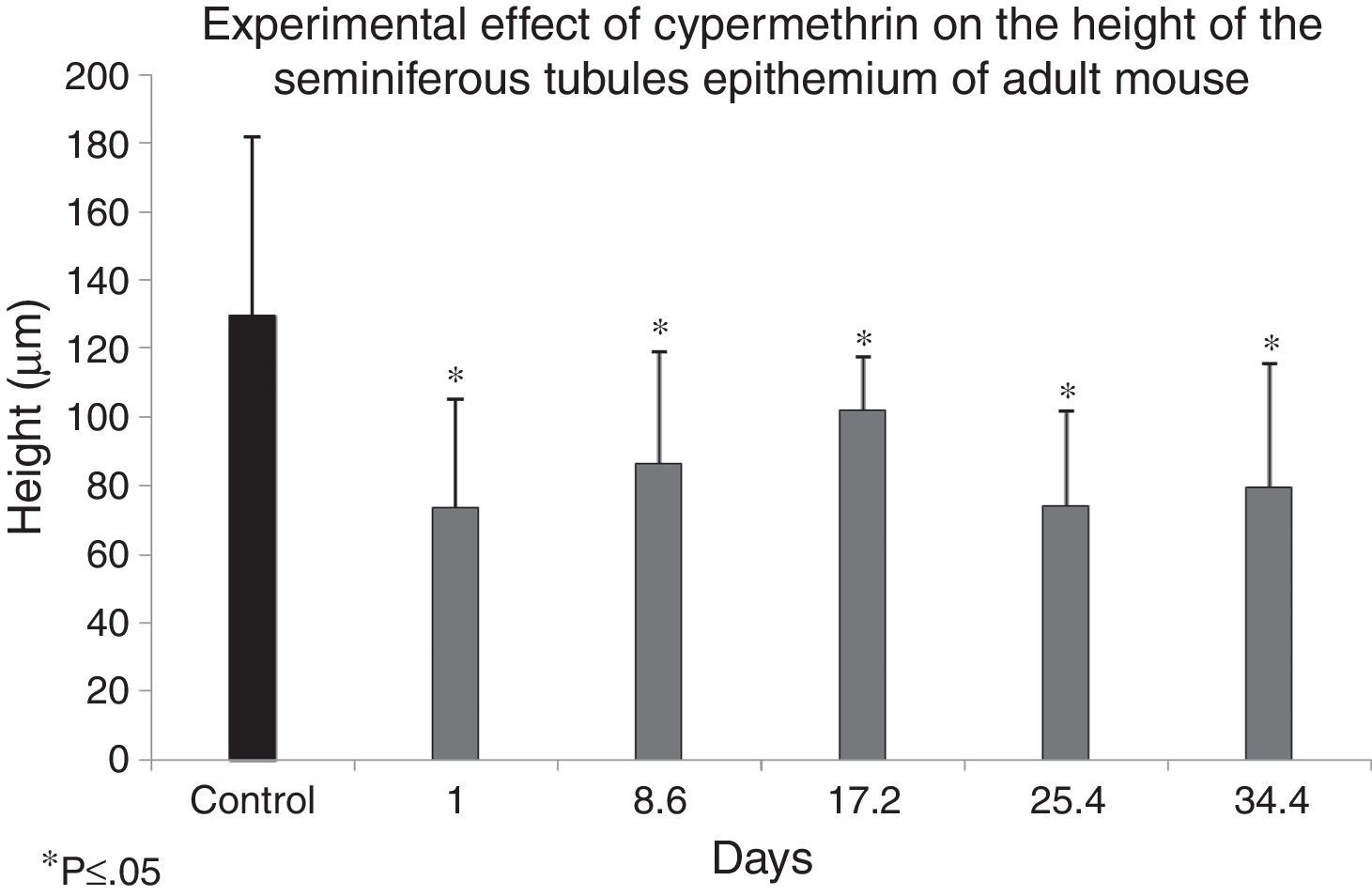

Fig. 3 shows the distribution of means and standard deviations of the measurements of seminiferous epithelium height from control and experimental groups, according to the experimental design (treatment with 1/5 LD50=485mg/kg of cypermethrin in 0.1ml of vegetable oil, intraperitoneally). Hence, the difference of means and standard deviations between the control group and each of the experimental groups were statistically significant according to the ANOVA analysis of variance (p<0.05). This suggests that cypermethrin may exert a significant effect on the organization of the cytoskeleton in Sertoli cells, and that these changes may be important in germ cell phenotype, considering that spermatogenesis occurs surrounded and nourished by Sertoli cells.

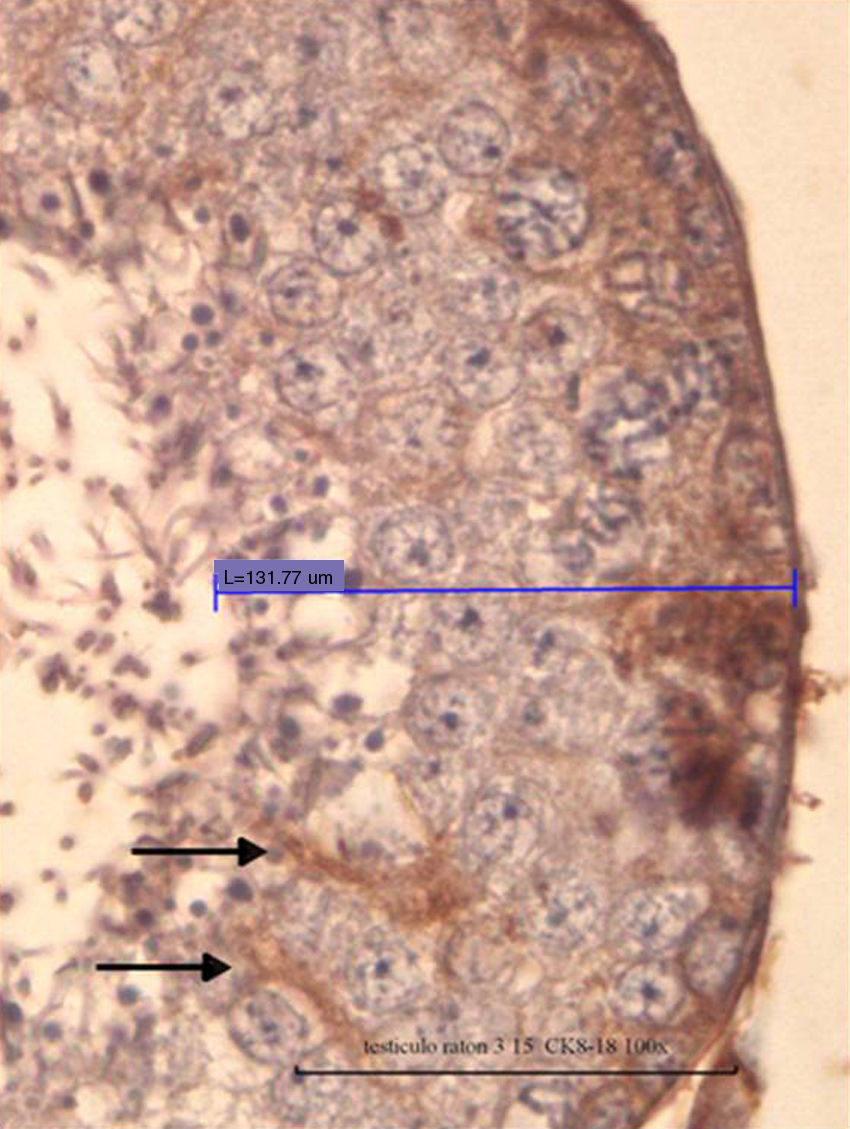

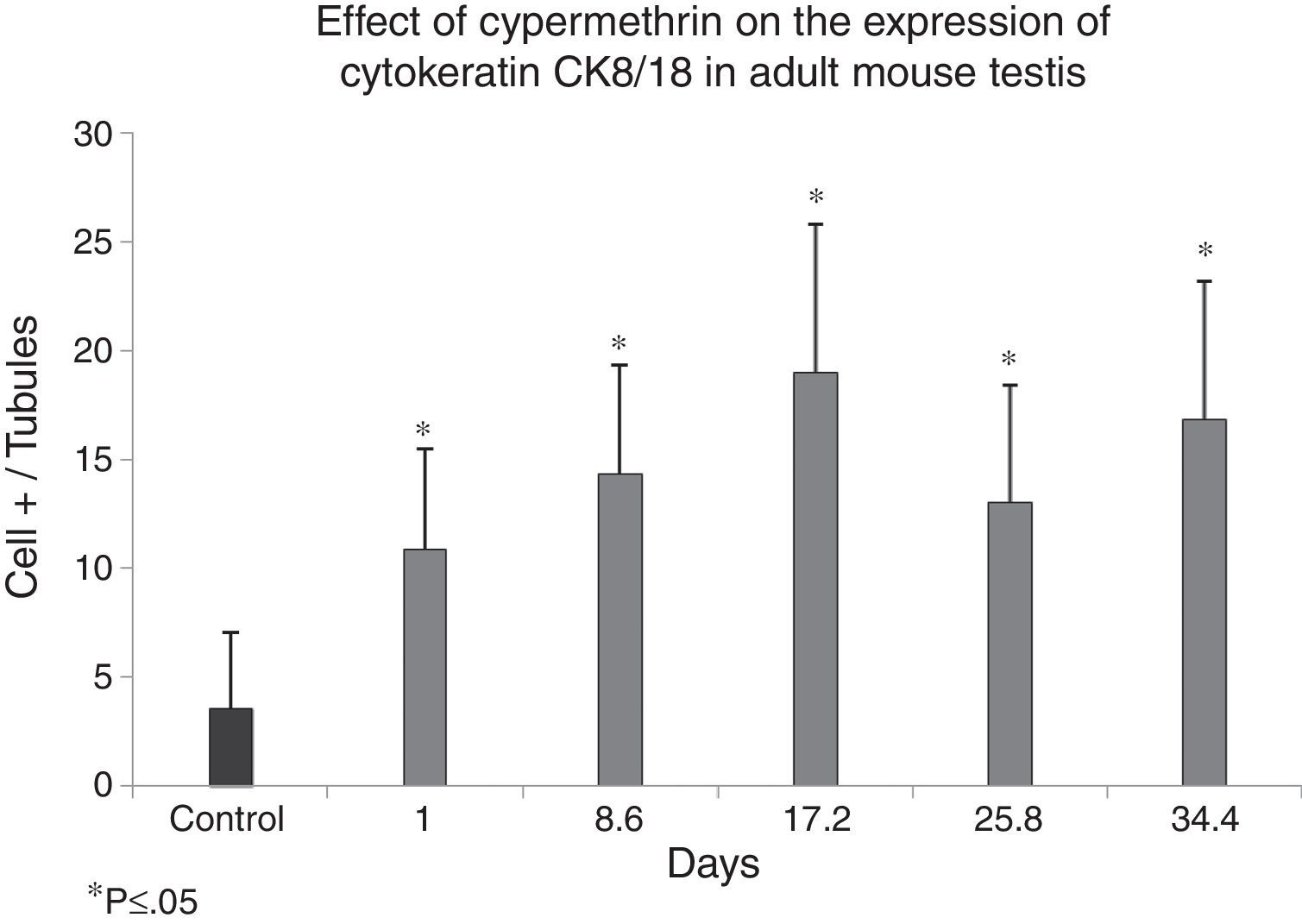

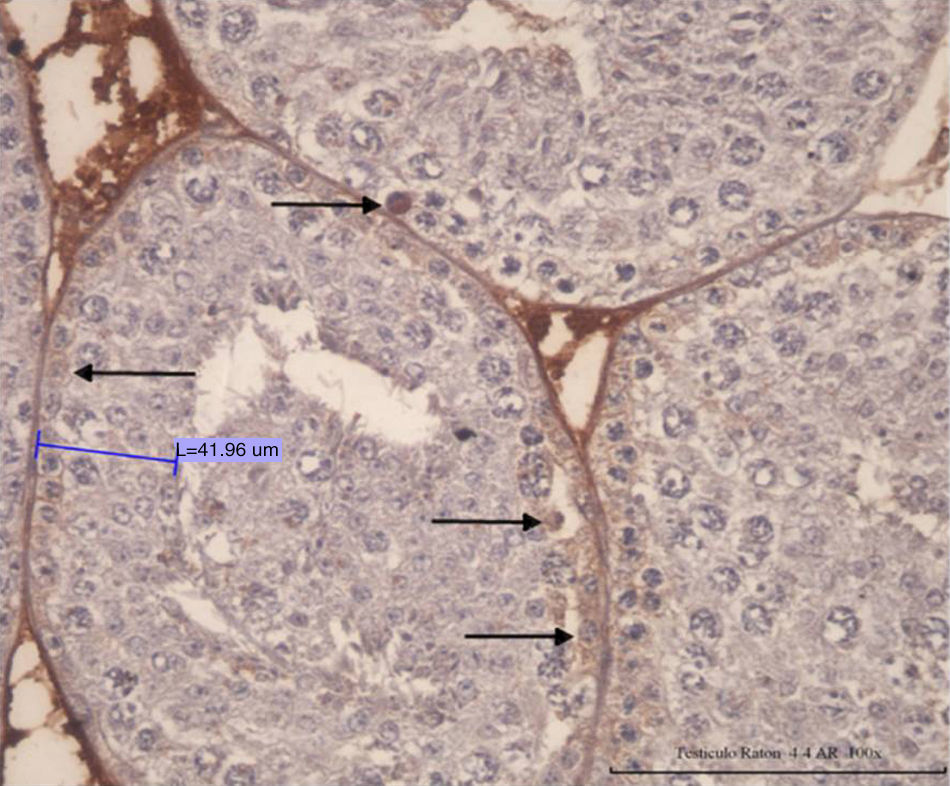

Immunohistochemical analysis of Ck-8/18Fig. 4 shows positive cells for Ck-8/18 identified by the intense brown color in their cytoplasm. The photomicrograph shows a positive reaction in the cytoplasm of the Sertoli cells from a control mouse testis (black arrow). Silhouettes of Sertoli cells showed them as tall cells with lateral branches. In Fig. 5, the bar graph shows the means and standard deviations for control and experimental groups according to the experimental design. Cypermethrin exerts acute (experimental group 1 day post inoculation), subacute (experimental groups 8.6 and 17.2 days post inoculation), and chronic effects (experimental groups 25.8 and 34.4 days post inoculation). These differences exerted by the action of cypermethrin are statistically significant (p<0.05).

Effect of cypermethrin on the differentiation state of Sertoli cells (cells CK8/18 +) via DAB/HRP specific IHC in mouse testis experimentally exposed to cypermethrin. Results are expressed by the ratio between the number of Sertoli cells with brown cytoplasm per total seminiferous tubules (tubular index). The graph is constructed with means and standard deviations.

The cylindrical shape of the Sertoli cell is closely related to its function in spermatogenesis. Cypermethrin induces a reduction of the height of the seminiferous epithelium (Sertoli cell in Fig. 3) and participates in the regulation of the expression of cytoskeletal proteins (cytokeratins Ck 8/18, Fig. 5). Both characteristics evaluated here represent signs of cellular dedifferentiation.

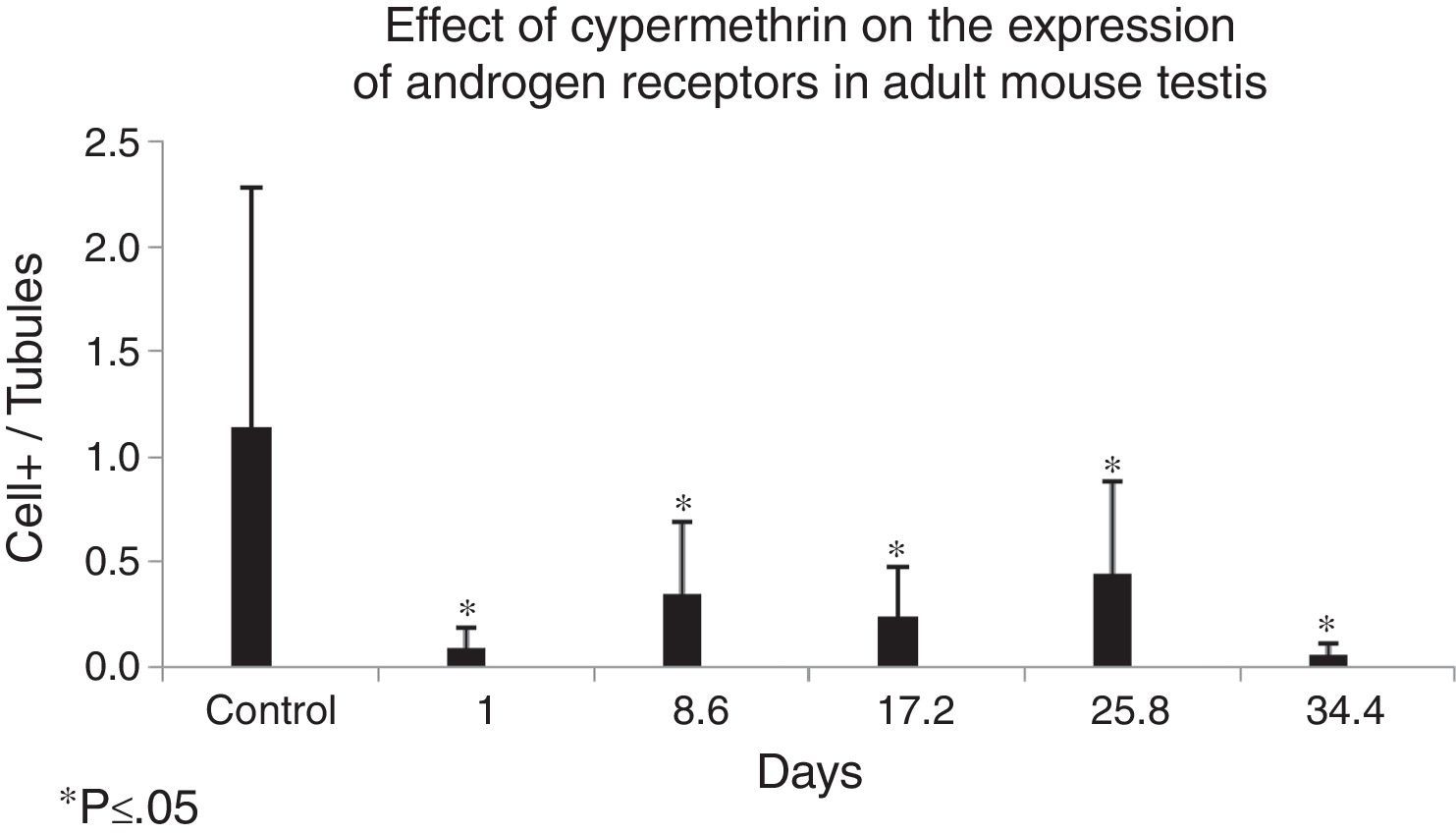

Immunohistochemical analysis of ARThe photomicrograph of Fig. 6 specifically shows a positive reaction in the nucleus of Sertoli cells from the testis of mouse in the control group (black arrows). Immunohistochemistry with specific anti androgen receptor (AR) antibody and the DAB-HRP detection system reveals the cells expressing the androgen receptor. Positive cells were observed with an intense brown precipitate in the nuclear area. Fig. 7 shows the means and standard deviations for the control versus the experimental groups. The differences amongst the control group and each one of the experimental groups were significantly significant (p<0.05).

Effect of cypermethrin on the expression of the androgen receptor in adult mouse testis shown by IHC detection of DAB/HRP on specific testis from mice exposed to cypermethrin. Results are expressed by the ratio between the number of Sertoli cells with brown cytoplasm per total seminiferous tubules (tubular index). The graph is constructed with means and standard deviations (*p<0.05).

Classically, cypermethrin is recognized as an extremely potent endocrine disruptor. Then, the presence of cypermethrin can alter both the expression of the androgen receptor synthesis machinery as can also act through deregulation (disruption) of the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis. Such mechanism might intensify the effects on cell dedifferentiation.

DiscussionSome studies have evaluated the central role of androgens in the control of spermatogenesis by acting directly on testicular somatic cells.12 The lack of androgens or androgen receptors indirectly affects the height of the seminiferous epithelium or the spermatogenesis since the germline stem cells do not express testosterone receptors.19

In the present research, a decrease in the height of epithelial cellularity of the seminiferous tubules in the presence of cypermethrin was evidenced. A recent study on the effects of cypermethrin in adult rats showed alterations in the structure of seminiferous tubules and in spermatogenesis. The authors concluded that damage on the male reproductive system may be attributed to an imbalance of circulating testosterone.20

The increased expression of the Ck-8/18 intermediate filaments induced by cypermethrin seen in our immunohistochemical assessment evidences the state of cell immaturity by augmenting the expression of this protein in the cytoskeleton. These results clearly supports the deleterious effect of cypermethrin on androgen receptor expression, thus reducing the total cellularity of the seminiferous epithelium but with an increase in the number of immature cells, as seen by the augmented number of cells expressing the Ck-8/18 protein and inducing its dysfunction via an antiandrogenic effect.

Cytokeratins belong to the protein family of intermediate filaments and constitute an important tool for cancer diagnosis. In the past decade, more than 20 cytokeratins have been identified.21 However, the intermediate filaments proteins Ck8 and Ck18, along with Ck19, are associated with the plasma membrane of all simple epithelia as part of the cytoskeleton matrix.22

Gao et al.23 described that cypermethrin may lead to gonadal dysgenesis in prepubertal male rats and alter functional mRNA and protein expression in Sertoli cells. Cypermethrin, orally administered (25mg/kg) in male Rattus rattus from post natal day 35 to day 70, decreased testosterone synthesis and its plasma and intratesticular levels by inhibiting both the mRNA synthesis and protein expression of StAR, an essential molecule for androgens synthesis that acts facilitating the entry of cholesterol into the Leydig cell for subsequent steroidogenesis.8

Wang et al.8 described that the levels of testicular and serum testosterone were significantly reduced in mice treated with cypermethrin. Other researchers showed an increase in germ cell apoptosis directly induced by various endocrine disruptors, including cypermethrin, a phenomenon interpreted as a cytotoxic event.24–26 Prolonged exposures to cypermethrin during puberty generate a marked adverse effect on the normal spermatogenetic cycle associated with low levels of intratesticular testosterone.

The major hormones that control the development of male germ cells are the gonadotropins FSH and LH. FSH acts via specific G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) present in Sertoli cells,27 constituting the primary mediator of androgen action on the control of spermatogenesis and, therefore, on the epithelial height of germ cells.25,28 A decrease in the activity of Leydig cells or the lack of androgen receptor expression in Sertoli cells decreases germ cell meiosis, which posteriorly manifests as a decrease in the cellularity or in the height of the seminiferous epithelium.

In studies with selective knockout for AR in Sertoli cells (SCARKO) mice, a complete blocking of the meiotic process was observed. One study pointed up the critical role of the AR-dependent regulation on the maturation or differentiation of germ cells in the seminiferous epithelium.12 Other authors described results such as arrest of the spermatogenesis during meiosis, infertility due to defective spermatogenesis, and hypotestosteronemia.28

In the immunohistochemical analysis of AR expression in the present study, a significant decrease in the number of cells expressing the androgen receptor in both the control and experimental groups was found, probably due to the lipid-based vehicle employed to inoculate the pesticide, which could affect the expression of steroid receptors by mediating cell signaling pathways for transcription and subsequent expression of AR, as well as by interfering with cholesterol entry into the cell for subsequent steroidogenesis.

Willems et al.,12 on a detailed study comparing SCARKO to control animals, showed that total lack of AR expression in Sertoli cells results in deficient formation of the blood-testis barrier. This research points up to morphological defects with alterations in the process of nuclear maturation accompanied by an aberrant positioning in the expression and localization of molecules related to cell adhesion and interaction and cytoskeletal dynamics.

The immunohistochemical analysis for the expression of AR in the present research found a significant decrease in the number of AR-expressing cells in all experimental groups, which implies that cypermethrin exerts an acute damage on this variable, interpreted as an anti-androgenic effect that possibly generates a cypermethrin-induced cellular dysfunction.

These results indicate that increasing endocrine disruption affects the reproduction of various cell populations by interfering with the expression of androgen receptors in Sertoli cells, leading to deterioration in the normal spermatogenic process and affecting the normal testicular morphology in individuals who have been exposed to endocrine disruptors like cypermethrin.

In recent years, the impact of environmental toxicants on reproduction and spermatogenesis has become urgent to understand in order to put into perspective the decline in male fertility levels. This has provoked a significant impact on other research topics such as the development of new technologies for male contraception that will provide additional tools for controlling population overgrowth and the development of new research lines focused on the development of new anticancer drugs that stop the process of cellular mitosis.

The results presented indicate that cypermethrin exerts an acute, subacute, and chronic effect on seminiferous epithelium height and Ck-8/18 protein expression, which demonstrates the immature cell stage induced by cypermethrin on Sertoli cells. In addition, cypermethrin alters the expression of nuclear androgen receptors in Sertoli cells. Overall, cypermethrin induces altered morphology and dysfunction on testicular tissue.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors state that the procedures followed conformed to the ethical standards of the responsible human experimentation committee and in agreement with the World Medical Association and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that in this article they are no patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that in this article they are no patient data.

Partial fundingProyecto UTA Mayor N° 4712-13.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.