Medical travel is a general term for all journeys made by a health professional, and are common practice for education and training as a significant globalised topic in modern medical education, and their relevance dates back far into history.

MethodsA historical-documental method is used in this study. It re-examines and discusses critically the J.P. Frank text De medicis peregrinationibus (medical travel) written in 1792.

FindingsThis paper enlightens on the meaning and usefulness of medical travels towards the end of the 18th century. A critical review of the text is carried out in order to compare medical travel and medical education towards the end of the 18th century with the same travel and education today.

The authors discuss a number of relevant points that Frank makes regarding travelling physicians, the meaning and usefulness of medical travels, as well as about a proposed curriculum for travelling physicians that could still be followed today.

ConclusionsAs a general conclusion, Frank's paper could be considered a seminal work on medical travel for educational purposes. His observations are still relevant today, reflected in students travelling abroad as part of mobility programmes in medical education.

Los viajes médicos, como término general para todo viaje realizado por un profesional de la salud, son una práctica habitual para su educación y capacitación, que conforma además un significativo tópico globalizado de la educación médica moderna, aunque su relevancia se remonte en la historia.

MétodoEsta investigación utiliza un método histórico-documental. Revisa y analiza críticamente el texto De medicis peregrinationibus (Viajes médicos) escrito por J.P. Frank en 1792.

HallazgosEste artículo explica el significado y la utilidad para el aprendizaje de los viajes médicos hacia finales del sigloxviii. Se lleva a cabo una revisión crítica del texto, tratando de comparar viajes médicos e instrucción médica hacia finales del sigloxviii con los mismos viajes y educación hoy en día.

Se discuten una serie de puntos relevantes que Frank realiza con respecto a los viajes médicos, su significado y la utilidad de estos, comentando una propuesta curricular para los médicos viajeros que bien podrían seguirse aún hoy.

ConclusionesComo conclusión general, el texto de Frank podría considerarse una obra fundamental sobre los viajes médicos con fines educativos. Sus observaciones son aún relevantes hoy en día, tal como se refleja en los estudios sobre estudiantes que viajan al extranjero en la actualidad como parte de programas de movilidad en su formación médica.

Medical travel is a significant globalised topic in modern medical education,1–3 but its relevance dates back far into history. So medical students who travel abroad today as part of the international mobility programs4 (i.e. Erasmus program), actually have quite distant forerunners. Ekeid5 talks about the mediaeval studiosi vagantes [student travellers] who wandered Europe seeking a better education. Grell and Arrizabalaga's6 work provides an overview of centres of medical excellence between 1500 and 1789, and a list of authors of books describing the adventure-like journeys of travelling physicians. Furthermore, the narratives of medical travellers from the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries are available in the collection by Spillane.7

The Latin term peregrinatio medica (medical travel) was coined to describe the journeys that medical students made to various centres of excellence seeking the best possible education, one which would have a positive impact on their teaching and medical practice upon their return. Prestigious hospitals and universities attracted large numbers of foreign students and qualified.

Medical travels were a usual practice for medical education along the 19th century. In this way, the great reformer of American medical teaching,8 Abraham Flexner enjoyed unequalled access to institutions and introductions to professors, researchers, and foreign ministers travelling abroad at the beginning of the 20th century.

In this paper, the term “medical travel” will be used in its original meaning, as opposed to that of other similar terms used today, such as “medical tourism” (seeking better medical treatment abroad), “travel Medicine” (treatment of health problems in travellers), “medical emigration” (medical professionals travelling abroad seeking a better quality of life and working conditions) or “expeditionary Medicine” (doctors in armies or on ships). We understand medical travel to refer to medical students, residents and qualified doctors improving their education in other countries, as well as outstanding doctors teaching and providing practical demonstrations abroad; this geographic mobility would be associated with career advancement.9

The aim of this paper is to provide a methodical overview of the many well-founded observations that Frank made two centuries ago in his seminal work on medical education, in order to identify implications for modern travels undertaken for educational purposes.

GlossingThe text and the contextAlthough medical travel was already quite common and travellers put their experiences down in writing upon their return, the first research into the topic in the medical sciences field only came when Johann Peter Frank10 provided a systematic overview of the subject in his chapter De medicis peregrinationibus in volume 11 of his magnum opus Delectus opusculorum medicorum [selected medical works], a true monumenta medica. Frank's work is not mentioned in Grell and Arrizabalaga's collection,6 and we have been unable to find any references to the chapter in the literature, despite the fact that it could be considered a pioneering document on medical travel in the historiography of medical education worldwide. Bonner11 mentions Frank merely as an expert in medical policy and great reformer of medical education who tried to tighten the connection between clinical practice and academic practice.

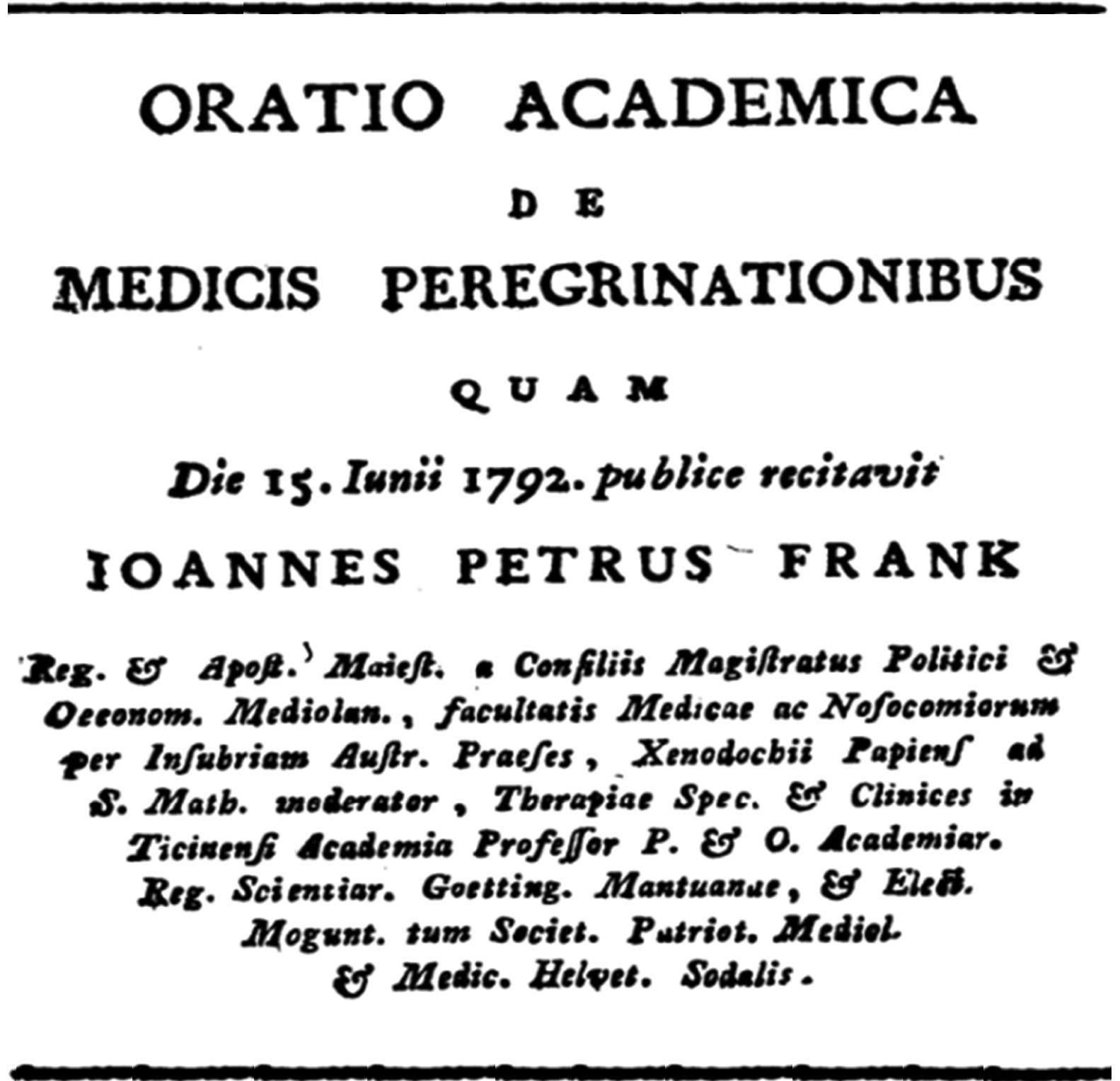

The chapter10 is 24 pages long (pages 359–382) with a title page (p. 357) providing a brief summary of the author's experience as a teacher, physician and hospital manager in a number of European cities. This chapter was originally written as an academic address (oratio academica, #22) given on June 15, 1792 at the University of Pavia (Italy) in this time under Austrian administration and where Frank was teaching observation and clinical therapies (Fig. 1).

The author and his relationship with medical educationFrank's interest in education in general, and medical education in particular, was already apparent at the beginning of his career in his doctoral thesis De educatione infantum physica [on physical education for children], which he wrote at Heidelberg University. This thesis was later published under the title Curas infantum physico-medicas exhibens [on the physical medical care of children] as essay number 22 in volume 13 of his magnum System einer vollständigen medicinischen polizey [a system of complete medical police].12 Nevertheless, it is in the fifth essay in volume 3, Discursus inauguralis de instituendo ad praxim medico professionis medicinae adeundae causa [inaugural lecture on the institutionalisation of medical practice as a medical profession for the treatment of the case], and in volume 6, where Frank12 proposes reforms to medical education. These included closer links between medicine and surgery, using prosection as a teaching method, compulsory training in Anatomical Pathology or the recording of medical data, laying the foundations for what would become epidemiology.

Frank10 also wrote De medicis peregrinationibus, an excellent piece on medical education which was written in Latin and has been largely ignored until now. This work is the focus of this paper. Frank wrote based on his extensive experience as a cosmopolitan traveller to numerous European hospitals and universities.

Breaking down the textIn the preamble, Frank10 says that he “will talk about medical travel so that Asclepius's followers can better perfect their art… very briefly outlining the positive effects of travel as well as the negative ones” (p. 359).

Frank makes a number of subtle distinctions, such as between “those who left their own country to learn medical theory and those who did it to better perfect their practice in the art” (p. 362). For him it was preferable that “those who already mastered everything in their particular field comfortably without problems in their own country were encouraged to train with foreigners for 3 years to improve their practice of the art” (p. 363). More recently, it has been recognised that the feasibility and usefulness of clinical and didactic medical training in global health issues starts at home.13

Frank10 goes on to ask questions such as “what can and should the State expect of the natural tendency of young doctors to travel to foreign provinces to learn?” (p. 363). Frank recognises that it is natural for men to travel and benefit from it, but “these benefits refer to a journey, and no more so than to those for a doctor” (p. 364). Because according to Frank, medical travel demands that the travellers “cast their eye, for a short period of time, almost just a glance, on the achievements of many men, who are very well versed in the art of healing, and record a faithful, indelible image of countless diseases” (p. 365).

Frank's experience of medical travel leads us to question the relevance of the wise host, as “you will see in many of them an unknown man or one deprived of the confidence of his people, a wanderer lacking in even the most basic principles of medicine, or a lying writer with a vile spirit, who cannot be credited with a discovery, but only with lying about it” (p. 365). Nevertheless, there is no need to go elsewhere because you will find in his place “other [teachers], who are loved by their country, although not famous amongst foreign men, but one must admire their distinguished expertise, their profound knowledge, their modesty and unique humanity in teaching eager young men” (p. 366).

Frank recommends “having a sound judgement of the doctors to visit and whether they deserve to be observed, read and studied, because often the results obtained are scarce… and not infrequently harm is done” (p. 366). Travelling physicians should not take from their journey “a few hypothetical anecdotes” (p. 366), “nor the despotic decrees of a simply eloquent writer enthusiastic about honours; nor erroneous methods, established through tradition, but the treasures of real practices that will be confirmed only by the authority of the combined experience of everyone, and which are only obtained in the company of expert men around the beds of the sick” (p. 367).

He advocates for universal medicine and surgery with “the same aspect for any people” (p. 367) as opposed to the established belief in particularistic medicine “from the same province”, supposedly because of “differences in the diverse situations of people, their way of life, their nature, their constitution and temperament” (p. 367). He therefore advocates for doctors being able to practise anywhere, providing as an example his own experience as a physician in various parts of Europe where he did not discover “any differences in diseases from one country to the next… in no place will arthritis not be arthritis, and the method for curing peripneumonia in Europe cures the same peripneumonia everywhere” (p. 368).

Furthermore, Frank clearly does not agree with travel by young, unqualified students, something that happens today with the European Union's Erasmus Program, which facilitates travel for undergraduates. He says: “the study of medicine must be undertaken with an honest and quite mature understanding, the spirit wanders towards the vices of that age,… bidding farewell to any type of contact with wise men” (p. 370). He goes on to attack the trend for medical travel amongst “new recruits who have not yet taken the common path in the art of healing, who cannot compare new, unprecedented methods with the old ones, nor prudently take advantage of conversation with men who are more famous in the art, nor offer any of their knowledge to those who ask” (p. 371). “It would be desirable for Princes and Magistrates… to send young men to such serious, and such costly, work, rather than far more innocent, still stammering youngsters” (p. 376). Such youngsters’ lack of empirical education is harmful for the sick, because “when they return home, to show off the fruits of their travels they often cut their throats vilely without sufficient understanding of any foreign method” (p. 372).

Frank's understanding of true medical education is based on “the knowledge of diseases, which must be carefully observed with absolute dedication which is not obtained through a quick walk through different provinces, but with effort over a long period of time, and with the mind focused on each specific case” (p. 373). Such medical education must be started in one's own country “through the study of practical medicine, under the supervision of an expert [we talk at this time of mentorship], before [they] go off because of a premature decision… a hasty journey and a brief exchange with foreigners” (p. 373), because when they come back and “they are amongst their people, faced with the most minor illness they hesitate, or go whaling in a tranquil river” (p. 373–4) [italics in the original].

Any doctor who undertakes a journey “should not travel hungry [for knowledge], as he will [then] be taken in with hospitality by foreigners, and will not be assigned the role of [mere] apprentice” (p. 374). It is therefore a good idea to bring “letters of recommendation from someone” (p. 376).

In the new locationOnce in his new setting, Frank recommends that the travelling physician “gains the respect, confidence and friendship of men whose art [he is] interested in studying, and have a more intimate relationship” (p. 375). He goes on to say that travellers should be prudent, and they “must be careful not to take part in any discussion against them amongst scholars, but reconcile the intents of all of them with their own, through cautious good sense… led by good education and the principles of simple prudence” (p. 382).

Frank talks about the complexities and difficulties of medical travel, of “sinister experiences in journeys for training” that lead to “premature and damaging opinions” (p. 375), of a lack of understanding between the traveller and his host, who stop having anything to do with one other when they have “barely crossed the first border”, of “false accounts of foreign things” (p. 375), and worse still of “falsehoods and testimonies of an ungrateful spirit in their absence” (p. 378).

Conversely, even if the travelling physician is well trained, he “still has to overcome the not insignificant difficulty of learning the languages of others” (p. 376) as “there is such enormous diversity in Latin pronunciation that it is common for everyone to give greater priority to the local language” (p. 376).

Furthermore, Frank attacks fleeting visits because “many travellers go through provinces so quickly and swiftly that they seem more like postmen… who are seeking the title of traveller rather than the secrets of science amongst foreigners” (p. 378). It is better to go to “those places where there are more opportunities to learn, and to live abroad long enough to be able to explain these things correctly” (p. 378).

A proposed curriculum for travelling physiciansFrank10 writes that “this educational journey has a clear aim: to understand the state of science in whatever nation, with what instruments, with what legal framework, and how successfully it is cultivated” (p. 379). Rejecting medical travel as an often unstructured experience as sometimes occurs today,14 he suggested a number of areas that experienced travelling physicians should consider and observe. Of these, the most specific to medicine are “way of life, superstitions that are harmful to public health, physical exercise, the method of physical and moral education, [and] the nature of the most frequent endemic, common or epidemic diseases” (p. 379). In fact, Frank proposes an entire curriculum, providing a long list of topics that should be studied during long journeys: “determining fertility, mortality; the establishment of laws for public health and safety; the regulations of colleges of physicians, surgeons and pharmacists, of medical academies, societies and museums; the organisation of hospitals, infirmaries, orphanages and prisons; in short they must consider each thing concerning the art [of medicine] itself and the discoveries of famous doctors and the methods of cure, and also the empirical remedies of the people” (p. 380).

Frank admits that it is not a question of time but of “an effort directed at intellection… in the examination of every thing that passes before their eyes, and with the help of daily notes on what they have observed, in the form of a faithful logbook” (p. 381). And such diaries must not be confused with the curious little books that travellers, particularly Germanic ones, used to call Amisticia [friendships] and which “were not lacking in signs of ostentation and vanity” (p. 381). Instead they should “mention anything related to science, collecting a treasury of observations on the cures of illnesses defined as more severe, and preserving in the depths of the mind the sayings of the foreign oracle” (pp. 381–2).

New guiding principles for the development of medical education curricula for medical undergraduates have been set out more recently.15

Updating: relevance of Frank's thoughts to medical travel todayFrank's proposals gain clear significance today in many areas. Firstly, in effective international clinical placements, because careful preparation and adequate support are critical if students and the host institutions are to gain maximum benefit from cross-cultural clinical placements. Close collaboration between the home and host institutions, along with student reflection, evaluation and the opportunity to incorporate new knowledge with other clinical experiences, are keys to a satisfactory outcome for all concerned.16

Some of the critics of the conception of medical travel set out by Frank offer key lessons on the obligation of appropriate debriefing for students returning from their health placements, which include the importance of affective learning, a pedagogy of discomfort, and medical ethics.17 By other side, we can infer from the Frank’ text questions also initially raised about the Erasmus program whether these program will provide the much-needed impetus to increase the educational status of the vast majority of novel medical students.

ConclusionsThis paper does not argue that all medical journeys are amateur, banal and fun,9 as an expensive holiday18 or a sort of clinical tourism19; rather that medical traveller is a sort of revived Odyssey involving its own hazards, penalties and, in extreme cases, physical and emotional risks.20 But the participants even undergraduates in these travels gain exposure to disease processes not found in their host countries.21

The complexity of this unique socio-educational phenomenon was described by Frank10 when he discusses problems relating to the absence of a suitable welcome for the traveller, the briefness of foreign stays and failure to select the correct place to visit, the immaturity of the students, the holiday-like nature of their trips, the need for qualified host teachers as real mentors, and the need for a training plan. Many of Frank's criticisms can just as easily be made of today's to certain mobility programmes especially to Erasmus programme18,22,23 especially this greater degree of mobility has highlighted the need to develop common educational standards to guide quality improvement efforts; notwithstanding according to Hensen4 the education of students from the medical field may benefit from the mobility programs objectives leading to a more permeable, comparable, and compatible education system across the world.

In short, all medical travel must be undertaken with an educational program which can be assessed to ensure that it is a truly useful endeavour which provides valuable insight into how international educational rotations can be created in order to be beneficial.24 This last sentence is obviously not in any way novel now but, in Frank's times at the end of the 18thcentury, it was a relevant statement adding something new to the literature about education of health professions. As Whitehead, Hodges and Austin25 say, there are prominent recurrent themes in medical education, not “new” themes; and every progress in medical education is slow and painful.26 The language as a problem for studying abroad is obviously also a barrier now and in the Frank's time.

Medical travel for medical education brings to mind the ongoing historical nature of educational issues in which Frank's work made it possible to identify a prominent and recurrent discourse of “new”. Not in vain, this episode of history of medical science could contribute to learning a complex process as the medical travel for medical education.27

FundingNone.

Conflicts of interestNone.