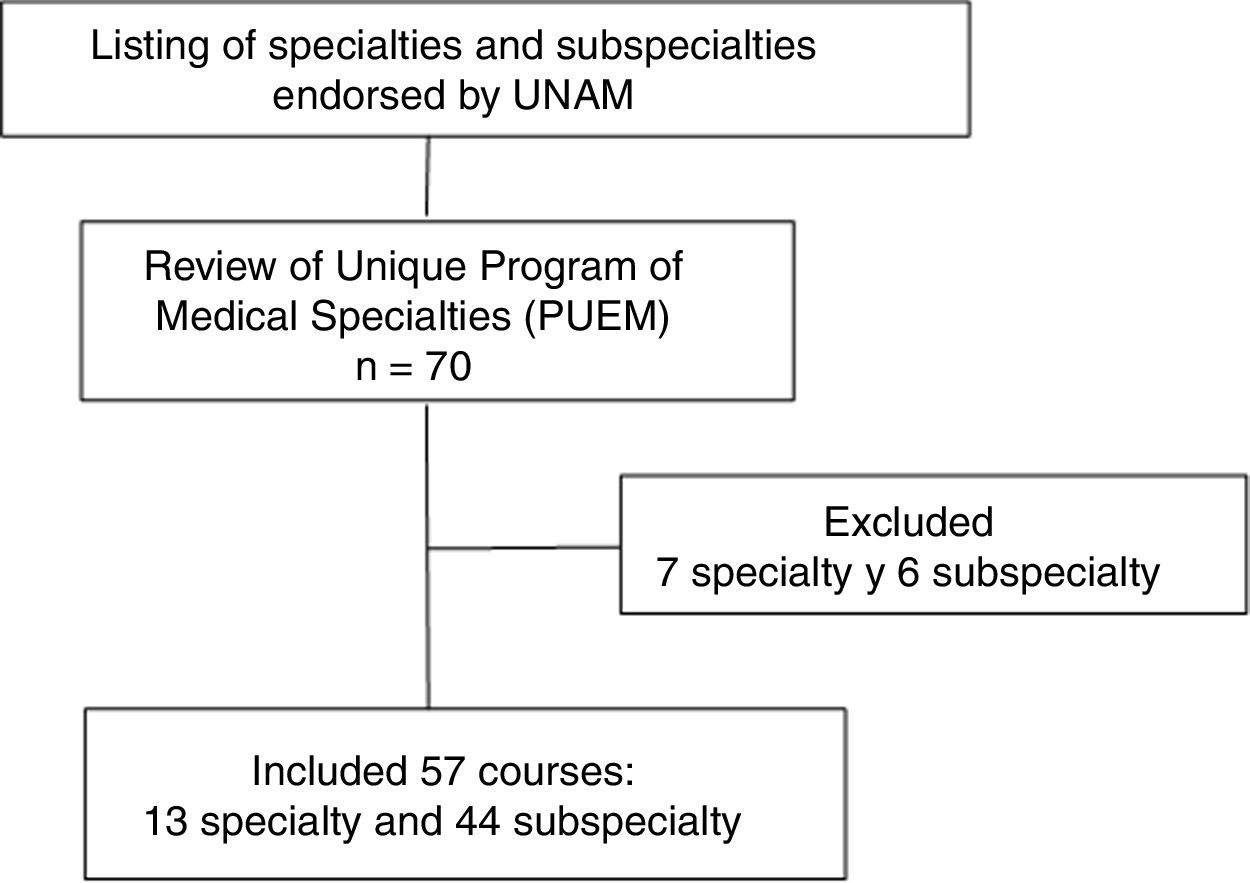

Obesity is a chronic disease with an increasing prevalence worldwide. Despite its importance for public health, studies indicate that medical specialists lack knowledge and skills for the management of patients with obesity. The aim of this study was to identify the inclusion of obesity topics in specialty/subspecialty residency medical programs endorsed by Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), and to assess its conformity within the current epidemiological context in Mexico and worldwide. A total of 70 specialty/subspecialty programs were identified, and the curricula of 57 were analyzed, after excluding those that did not involve contact with patients. These were classified into three groups: (1) those that described specific topics/skills on obesity; (2) those that mentioned the word “obesity” without describing specific knowledge/skills, and (3) those that did not include any mention of obesity. Only six (10.5%) programs described knowledge/skills to be developed for obesity treatment, 7 (12.3%) mentioned the term “obesity”, and 44 (77.2%) did not consider obesity within their curricula. The results indicate that medical residents lack adequate training for obesity management. A proposal is made for need to integrate the current knowledge of obesity into a multidisciplinary context in the specialty/subspecialty programs in order to provide specialists with tools and skills for the appropriate treatment of obesity.

La obesidad es una enfermedad crónica cuya prevalencia ha aumentado. Los estudios indican que los médicos especialistas carecen de conocimientos/habilidades para el tratamiento de pacientes con obesidad. Nuestro objetivo fue identificar la inclusión de temas de obesidad en los programas de residencia en especialidades/subespecialidades médicas respaldadas por la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) y analizar su conformidad con el contexto epidemiológico en México y el mundo. Identificamos 70 programas de especialidad/subespecialidad y analizamos los planes de estudio de 57, luego de excluir aquellos que no involucran contacto con pacientes. Los clasificamos en 3 grupos: 1) aquellos que describieron conocimientos/habilidades específicos sobre obesidad; 2) aquellos que mencionaron la palabra obesidad sin describir conocimientos/habilidades específicos, y 3) aquellos que no incluyeron ninguna mención de obesidad. Solo 6 programas (10,5%) describieron los conocimientos/habilidades a desarrollar para el tratamiento de la obesidad, 7 (12,3%) mencionaron el término obesidad y 44 (77,2%) no consideraron la obesidad dentro de sus programas. Los resultados indican que los residentes carecen de una formación adecuada para el manejo de la obesidad. Proponemos integrar el conocimiento de obesidad en un contexto multidisciplinario en los programas de especialidad/subespecialidad para proporcionar a los especialistas herramientas y habilidades para el tratamiento adecuado de la obesidad.

Obesity is a chronic disease that in recent years has had a progressive increase in its prevalence worldwide, and Mexico is no exception. It comprises one of the main risk factors for the development and progression of chronic and acute diseases, ranging from diabetes mellitus, to high blood pressure, to different types of cancer.1,2 According to the most recent National Health and Nutrition Survey in 2016 in Mexico (ENSANUT MC 2016), the prevalence of overweight and obesity in adults was 72.5%: 39.2% for overweight and 33.3% for obesity.3

It has been documented that specialty medical interventions lack a nutritional approach, and that this is correlated with an increase in the incidence of morbidity and mortality due to diseases such as obesity, diabetes, coronary disease, high blood pressure, cerebrovascular events, and some types of cancer, among others.4,5 Despite knowledge on the relationship between obesity and the prevention and treatment of these diseases, the majority of physicians in their clinical practices do not place the necessary emphasis on the need to treat obesity and on the prescription of a diet to achieve this.6,7 Galuska et al.8 reported the results of a survey of 12,835 patients with obesity based on indications given by their physician at their medical appointments; only 42% of patients received an indication by the health professional on losing weight, suggesting some recommendations. Scott et al.9 evaluated the physicians’ intervention with regard to the excess weight of their patients, detecting that of the 376 surveys among patients with overweight and obesity, only 17% addressed the subject, and only 11% of patients received recommendations to achieve weight loss.

Formerly, it was considered that physicians had little interest in and gave scarce importance to the obesity of their patients8,9; however, recently, studies have been conducted on nutrition and obesity knowledge in medical residents in different parts of the world, as well as their attitude on confronting the diagnosis and treatment of obesity. In these studies it has been concluded that 98% of medical residents consider that the diagnosis and treatment of obesity in their patients is important; however, they report that they have few tools with regards to knowledge to carry out a comprehensive diagnosis and to treat obesity, and they recognize that their therapeutic approach is insufficient for the management of the disease.10 In a survey of primary-care physicians, only 31% mentioned receiving training for the management of obesity in their medical residency, and those who did acquire skills were more likely to address diet or exercise with their patients with obesity (59 vs. 29%).11 A study carried out by the New York University with medical residents (Internal Medicine, Pediatrics, Psychiatry) found that nearly half of the physicians could not respond adequately to their patients’ questions with respect to the treatment of obesity; more than 34% of the physicians were unable to establish adequate objectives regarding weight loss, lifestyle changes, and physical activity; 59% informed that they possessed inadequate competency for using the motivational interview with their patients, and 39% reported not having adequately conducted a brief intervention and orientation for weight loss in their patients. The latter indicates that, even in cases in which the physicians recommend that their patients lose weight, they do not necessarily perform this in an adequate manner.12

In a study conducted in the U.S. state of Louisiana, the interventions carried out by Internal Medicine residents in the first-contact office appointment were evaluated by means of questionnaires applied to patients; it was found that 79% of patients received instructions on losing weight, but only 28% received specific weight-loss recommendations. Of these, 17% remembered the advice given for diet modification, and only 5% received recommendations to increase physical activity. Solely an additional 5% recalled that they were provided with weight-loss strategies such as combining diet and exercise, and 1% remembered only being informed of other weight-loss options, such as pharmacological and surgical treatments. It was also found that patients who received advice on weight loss better understood the association between obesity and health problems, as well as the benefit of weight loss.13

Due to the importance of obesity in many diseases, in the different international guidelines for specific diseases, weight loss is suggested as a fundamental part of their treatment. To cite a few, the guidelines of the Global Initiative for Asthma Guidelines (GINA 2015) for the diagnosis and treatment of asthma, mentions the loss of 5–10% of the weight as part of the treatment in patients with asthma and obesity.14 The American Society of Neurology and Neurosurgery states treatment for obesity among the core recommendations for management of idiopathic intracranial hypertension.15 NICE Guidelines for the management of osteoarthritis also indicate weight loss as part of the management of osteoarthritis in patients with overweight and obesity.16 However, none of these guidelines provide specific recommendations for the management of obesity, and the available body of information suggests that medical specialists possess few skills for the treatment of obesity.

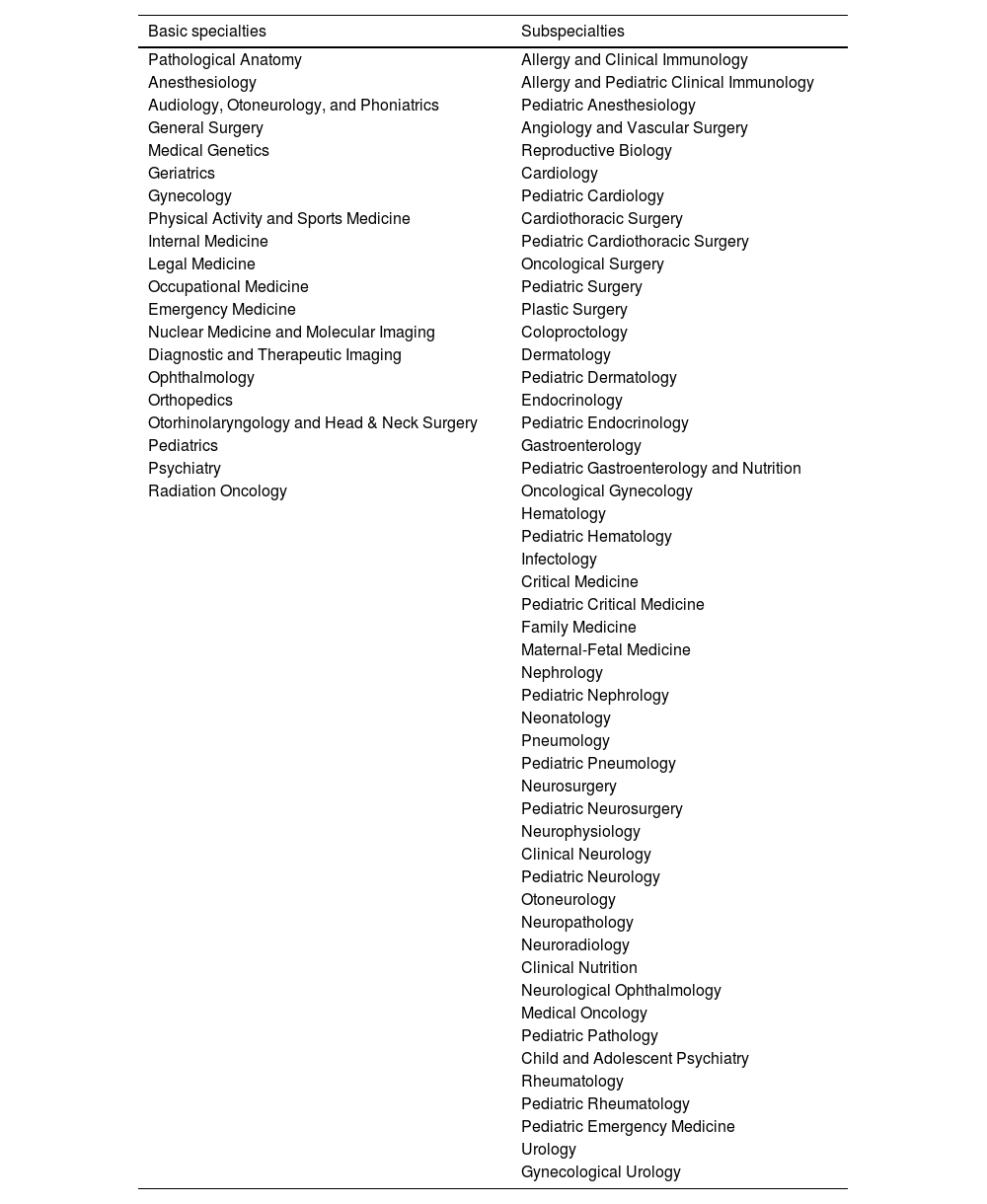

In Mexico, academic programs for the training of medical specialists (medical residency programs) require university endorsement. The main universities of each region carry out academic programs and evaluate students in terms of their adequate training. The Mexican National Autonomous University (in Spanish, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México or UNAM) is the guiding institution that has had the greatest impact on medical specialty programs (residency programs) throughout Mexico; it grants its university endorsement and has a “Unified Curriculum of Medical Specialties” (Plan Único de Especializaciones Médicas or PUEM) which attempts to establish and standardize the knowledge necessary for training of medical specialists prepared at the different headquarter hospitals in the country. The process of medical specialization consists of two types of training that comprise specialty and subspecialty programs. The specialty programs refer to the basic specialties (Table 1) that are accessed at the end of medical school. A basic specialty is required as a prerequisite to access a subspecialty program. Given the current epidemiological overview in Mexico and in many countries around the world, and the need to have health personnel prepared to evaluate, treat, and guide patients with this disease, our objective was to document the inclusion of obesity topics in academic specialty and subspecialty programs endorsed by UNAM.

Listing of the PUEM-UNAM specialty and subspecialty programs.

| Basic specialties | Subspecialties |

|---|---|

| Pathological Anatomy | Allergy and Clinical Immunology |

| Anesthesiology | Allergy and Pediatric Clinical Immunology |

| Audiology, Otoneurology, and Phoniatrics | Pediatric Anesthesiology |

| General Surgery | Angiology and Vascular Surgery |

| Medical Genetics | Reproductive Biology |

| Geriatrics | Cardiology |

| Gynecology | Pediatric Cardiology |

| Physical Activity and Sports Medicine | Cardiothoracic Surgery |

| Internal Medicine | Pediatric Cardiothoracic Surgery |

| Legal Medicine | Oncological Surgery |

| Occupational Medicine | Pediatric Surgery |

| Emergency Medicine | Plastic Surgery |

| Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging | Coloproctology |

| Diagnostic and Therapeutic Imaging | Dermatology |

| Ophthalmology | Pediatric Dermatology |

| Orthopedics | Endocrinology |

| Otorhinolaryngology and Head & Neck Surgery | Pediatric Endocrinology |

| Pediatrics | Gastroenterology |

| Psychiatry | Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition |

| Radiation Oncology | Oncological Gynecology |

| Hematology | |

| Pediatric Hematology | |

| Infectology | |

| Critical Medicine | |

| Pediatric Critical Medicine | |

| Family Medicine | |

| Maternal-Fetal Medicine | |

| Nephrology | |

| Pediatric Nephrology | |

| Neonatology | |

| Pneumology | |

| Pediatric Pneumology | |

| Neurosurgery | |

| Pediatric Neurosurgery | |

| Neurophysiology | |

| Clinical Neurology | |

| Pediatric Neurology | |

| Otoneurology | |

| Neuropathology | |

| Neuroradiology | |

| Clinical Nutrition | |

| Neurological Ophthalmology | |

| Medical Oncology | |

| Pediatric Pathology | |

| Child and Adolescent Psychiatry | |

| Rheumatology | |

| Pediatric Rheumatology | |

| Pediatric Emergency Medicine | |

| Urology | |

| Gynecological Urology |

Abbreviation: PUEM-UNAM: “Unified Curriculum of Medical Specialties” from National Autonomous University of Mexico (in Spanish: Plan Único de Especializaciones Médicas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México).

We made a listing of all the specialty and subspecialty programs included in the Unified Curriculum of Medical Specialties (PUEM) 2016 from the UNAM Postgraduate Medicine link (http://www.fmposgrado.unam.mx/ofertaAcademica/esp/esp.html). Of a total of 70 programs, 20 were specialty and 50 were subspecialty courses. We reviewed the academic contents of all 70 programs of the PUEM obtained from the files of UNAM's Postgraduate Studies Division (Table 1).

We excluded seven specialties (Pathological Anatomy, Anesthesiology, Medical Genetics, Legal Medicine, Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, Diagnostic and Therapeutic Imaging, and Radiation Oncology) and six subspecialties (Pediatric Anesthesiology, Neurophysiology, Otoneurology, Neuropathology, Neuroradiology, and Pediatric Pathology) that do not involve contact with patients that give rise to prescription and intervention for the treatment of obesity (Fig. 1). We conducted a search in PubMed during the period between 2004 and 2014 for original and review articles dealing with the importance of obesity in each of the topics of the remaining 57 specialty and subspecialty programs.

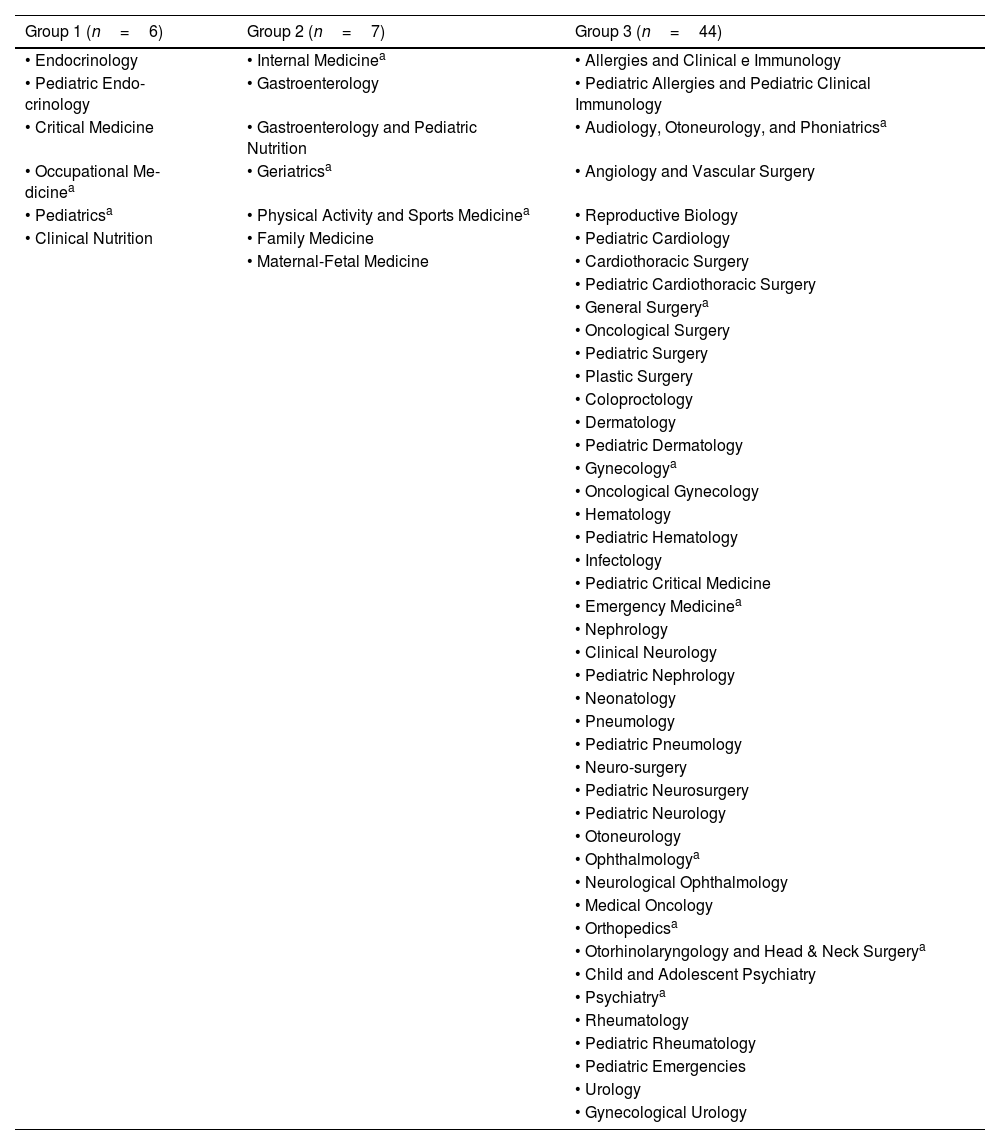

We identified the main conditions that being a comorbidity for obesity pose (a) an opportunity for prevention, or (b) a treatment problem for the subspecialist in question that is unobjectionably determined by obesity. We carried out a review of each of the programs, identifying the topics and skills (when available) to be developed focused on the subject of nutrition, specifically in the area of obesity. We tried to quantify the hours assigned to teaching on obesity issues or topics, which was not possible because none of the programs handled the allocation of hours for each of the topics, and only the titles of the topics to be discussed are mentioned. We classified the programs into three groups (Table 2) according to the information provided: those that describe the specific topics or skills to be developed on obesity (Group 1), those that mention the word obesity within its contents without describing more specific knowledge or skills (Group 2), and those that do not include any mention of obesity as a topic within the program (Group 3). For Group 1, we reviewed the course syllabi and identified the specific topics or skills related to nutrition, more specifically, to obesity (Table 3).

Classification of specialty/subspecialty programs in three groups according to the content of obesity topics within their academic programs.

| Group 1 (n=6) | Group 2 (n=7) | Group 3 (n=44) |

|---|---|---|

| • Endocrinology | • Internal Medicinea | • Allergies and Clinical e Immunology |

| • Pediatric Endo-crinology | • Gastroenterology | • Pediatric Allergies and Pediatric Clinical Immunology |

| • Critical Medicine | • Gastroenterology and Pediatric Nutrition | • Audiology, Otoneurology, and Phoniatricsa |

| • Occupational Me-dicinea | • Geriatricsa | • Angiology and Vascular Surgery |

| • Pediatricsa | • Physical Activity and Sports Medicinea | • Reproductive Biology |

| • Clinical Nutrition | • Family Medicine | • Pediatric Cardiology |

| • Maternal-Fetal Medicine | • Cardiothoracic Surgery | |

| • Pediatric Cardiothoracic Surgery | ||

| • General Surgerya | ||

| • Oncological Surgery | ||

| • Pediatric Surgery | ||

| • Plastic Surgery | ||

| • Coloproctology | ||

| • Dermatology | ||

| • Pediatric Dermatology | ||

| • Gynecologya | ||

| • Oncological Gynecology | ||

| • Hematology | ||

| • Pediatric Hematology | ||

| • Infectology | ||

| • Pediatric Critical Medicine | ||

| • Emergency Medicinea | ||

| • Nephrology | ||

| • Clinical Neurology | ||

| • Pediatric Nephrology | ||

| • Neonatology | ||

| • Pneumology | ||

| • Pediatric Pneumology | ||

| • Neuro-surgery | ||

| • Pediatric Neurosurgery | ||

| • Pediatric Neurology | ||

| • Otoneurology | ||

| • Ophthalmologya | ||

| • Neurological Ophthalmology | ||

| • Medical Oncology | ||

| • Orthopedicsa | ||

| • Otorhinolaryngology and Head & Neck Surgerya | ||

| • Child and Adolescent Psychiatry | ||

| • Psychiatrya | ||

| • Rheumatology | ||

| • Pediatric Rheumatology | ||

| • Pediatric Emergencies | ||

| • Urology | ||

| • Gynecological Urology |

Group 1: program describes the specific topics or skills on obesity to be developed.

Group 2 program mentions the word obesity in its academic content, without describing more specific knowledge or skills to be acquired.

Group 3: program does not include obesity as a topic.

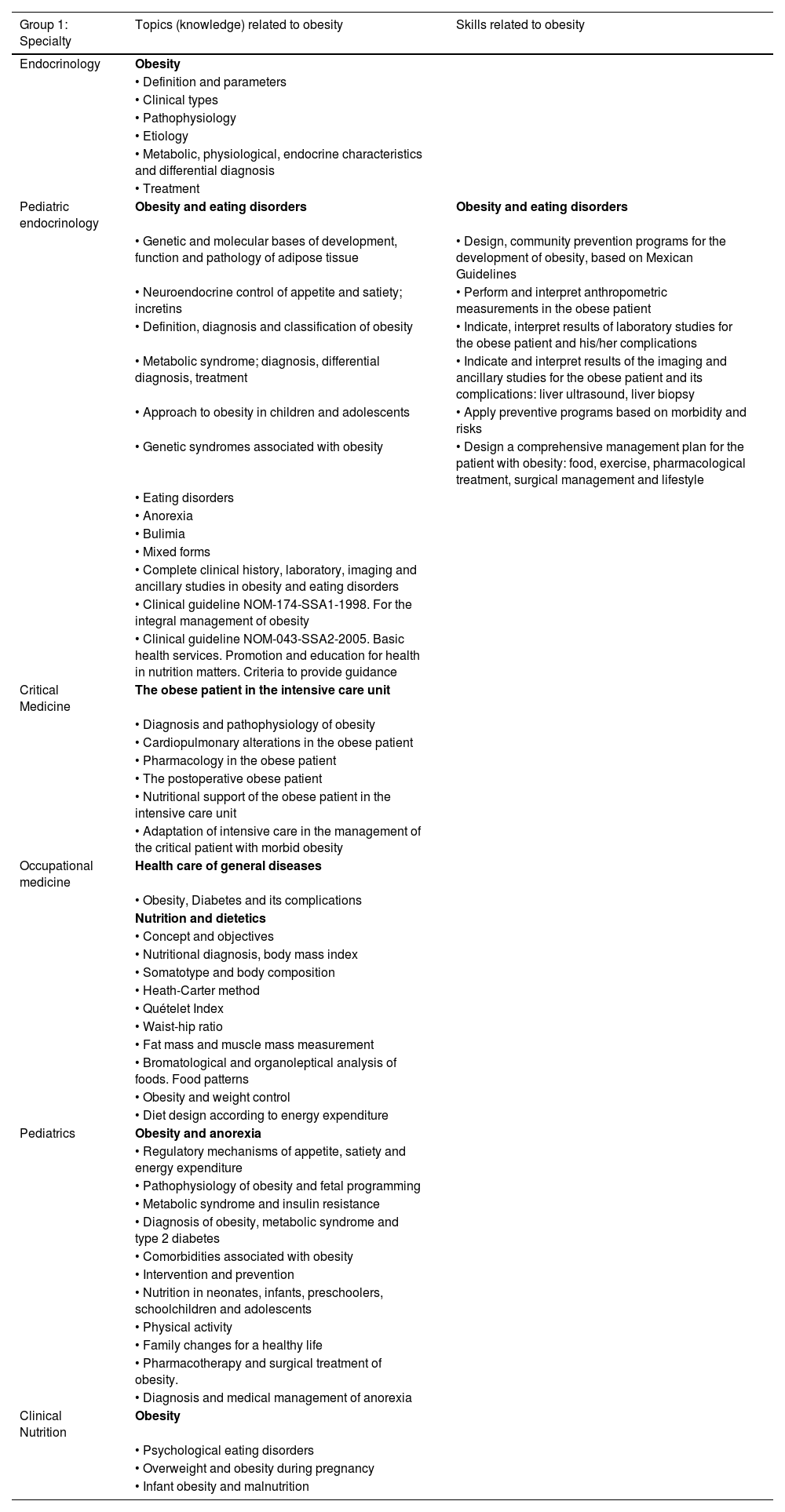

Obesity contents (knowledge or skills) in specialties from Group 1.

| Group 1: Specialty | Topics (knowledge) related to obesity | Skills related to obesity |

|---|---|---|

| Endocrinology | Obesity | |

| • Definition and parameters | ||

| • Clinical types | ||

| • Pathophysiology | ||

| • Etiology | ||

| • Metabolic, physiological, endocrine characteristics and differential diagnosis | ||

| • Treatment | ||

| Pediatric endocrinology | Obesity and eating disorders | Obesity and eating disorders |

| • Genetic and molecular bases of development, function and pathology of adipose tissue | • Design, community prevention programs for the development of obesity, based on Mexican Guidelines | |

| • Neuroendocrine control of appetite and satiety; incretins | • Perform and interpret anthropometric measurements in the obese patient | |

| • Definition, diagnosis and classification of obesity | • Indicate, interpret results of laboratory studies for the obese patient and his/her complications | |

| • Metabolic syndrome; diagnosis, differential diagnosis, treatment | • Indicate and interpret results of the imaging and ancillary studies for the obese patient and its complications: liver ultrasound, liver biopsy | |

| • Approach to obesity in children and adolescents | • Apply preventive programs based on morbidity and risks | |

| • Genetic syndromes associated with obesity | • Design a comprehensive management plan for the patient with obesity: food, exercise, pharmacological treatment, surgical management and lifestyle | |

| • Eating disorders | ||

| • Anorexia | ||

| • Bulimia | ||

| • Mixed forms | ||

| • Complete clinical history, laboratory, imaging and ancillary studies in obesity and eating disorders | ||

| • Clinical guideline NOM-174-SSA1-1998. For the integral management of obesity | ||

| • Clinical guideline NOM-043-SSA2-2005. Basic health services. Promotion and education for health in nutrition matters. Criteria to provide guidance | ||

| Critical Medicine | The obese patient in the intensive care unit | |

| • Diagnosis and pathophysiology of obesity | ||

| • Cardiopulmonary alterations in the obese patient | ||

| • Pharmacology in the obese patient | ||

| • The postoperative obese patient | ||

| • Nutritional support of the obese patient in the intensive care unit | ||

| • Adaptation of intensive care in the management of the critical patient with morbid obesity | ||

| Occupational medicine | Health care of general diseases | |

| • Obesity, Diabetes and its complications | ||

| Nutrition and dietetics | ||

| • Concept and objectives | ||

| • Nutritional diagnosis, body mass index | ||

| • Somatotype and body composition | ||

| • Heath-Carter method | ||

| • Quételet Index | ||

| • Waist-hip ratio | ||

| • Fat mass and muscle mass measurement | ||

| • Bromatological and organoleptical analysis of foods. Food patterns | ||

| • Obesity and weight control | ||

| • Diet design according to energy expenditure | ||

| Pediatrics | Obesity and anorexia | |

| • Regulatory mechanisms of appetite, satiety and energy expenditure | ||

| • Pathophysiology of obesity and fetal programming | ||

| • Metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance | ||

| • Diagnosis of obesity, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes | ||

| • Comorbidities associated with obesity | ||

| • Intervention and prevention | ||

| • Nutrition in neonates, infants, preschoolers, schoolchildren and adolescents | ||

| • Physical activity | ||

| • Family changes for a healthy life | ||

| • Pharmacotherapy and surgical treatment of obesity. | ||

| • Diagnosis and medical management of anorexia | ||

| Clinical Nutrition | Obesity | |

| • Psychological eating disorders | ||

| • Overweight and obesity during pregnancy | ||

| • Infant obesity and malnutrition |

Of the 57 specialty programs analyzed, only six were included in Group 1 (Endocrinology, Pediatric Endocrinology, Critical Medicine, Occupational Medicine, Clinical Nutrition, and Pediatrics), representing 10.5% of the courses included in the study. In Group 2, we included seven programs (Internal Medicine, Gastroenterology, Pediatric Gastroenterology, Geriatrics, Physical Activity and Sports Medicine, Family Medicine, and Fetal Maternal Medicine), which represent 12.3% of the specialties. Group 3 included 44 specialties, that is, 77.2% of the programs analyzed (Table 2).

Table 3 lists the topics, both specific knowledge and skills, included in programs in Group 1. It is interesting to note that topics are related to genetic and molecular aspects of obesity, clinical definitions, regulation of appetite and satiety, physiology, metabolism, comorbidities, diverse aspects of clinical assessment and treatment, and clinical guidelines, among others. Only one specialty (Pediatric Endocrinology) addressed the specific skills to be developed during the program and all of them refer to practical aspects such as designing community programs, performing and evaluating anthropometric measurements, interpreting results of laboratory studies or designing a comprehensive management plan for the patient with obesity. No skills regarding the understanding of the person with obesity, the relevance of addressing the issue of overweight, empathic and respectful ways to initiate a conversation about weight, how to address patient barriers, among others were included.17

DiscussionRealitiesDespite the growing prevalence of obesity and its comorbidities in Mexico, and the great importance of this issue on the current public health context, our results show that this epidemiological information has not permeated medical specialty programs. Therefore, it is possible to assume that medical residents do not have sufficient training to deal with obesity issues. According to our results, only 10.5% (Group 1) of the programs describe in depth the knowledge and skills (only one specialty program) required for the treatment of obesity, but without specifying learning objectives and time to achieve them. The rest of the programs only mention the word obesity within their contents without describing more specific knowledge or skills (12.3%, Group 2) or do not even consider it (77.2%, Group 3). This leads us to suppose that for 89.5% of the programs, obesity does not seem to be a determinant of health status of individuals, or an important issue associated with the evolution of their distinct diseases.

ReflectionsOur study revealed the existence of a gap in the teaching of obesity in medical specialty programs in Mexico; this represents a problem in terms of training medical specialists who are not sensitive to the importance of the subject, which can lead to deficient diagnosis and poor treatment of patients with obesity in whom their disease – i.e., the main reason for their medical appointment –, would evolve in a manner directly related with the good or poor management of obesity. The latter could be occurring even in medical specialties that require knowledge of obesity in order to provide patients with a better treatment.

To our knowledge, there are no studies that evaluate the content of obesity topics within the academic specialty programs, at least in Mexico; however, this lack of introduction toward obesity as a disease within the training of physicians has been studied. It has even been informed in previous studies in other parts of the world that there have been certain attitudes of rejection of medical students toward patients with obesity, a situation that necessarily promotes a poor doctor–patient relationship, and therefore a deficient intervention with regard to this health problem.18–20

Due to the complexity of obesity as a disease, at present the international guidelines for its treatment indicate the need for multidisciplinary treatment, which includes a medical specialist, a dietitian, a psychologist, and a physical therapist, all trained to treat patients with obesity.21–23 It has been documented that the experience deriving from multidisciplinary management in different areas of Medicine presents many difficulties. In the first place, multidisciplinary management requires human and economic resources that are not necessarily present at all of the institutions. On the other hand, the multidisciplinary groups are not in themselves the solution, as a study conducted in Italy demonstrates, in which it was found that there are barriers and conflicts within multidisciplinary teams because, on occasion, they do not entertain the same goals or interests in the treatments. Management of patients by multidisciplinary teams does not always confer a better diagnosis on the patient.24 Despite the latter, multidisciplinary teams have demonstrated achieving better results with regard to weight loss, treatment adherence, and improvement of comorbidities associated with obesity,25 and it seems obvious that the multidisciplinary approach to the study and treatment of patients with obesity has led to the construction of therapeutic proposals of recognized efficacy. At present, we have access to clinical guidelines for the treatment of obesity that encompass multidisciplinary knowledge, leading to proposals for the diagnosis, classification, and treatment of patients with obesity. We believe that bringing this knowledge to the different specialists involved in the care of these patients can train them to initiate a dialog on the subject, make an appropriate diagnosis, initiate and, as far as possible, give way to the treatment of obesity.26

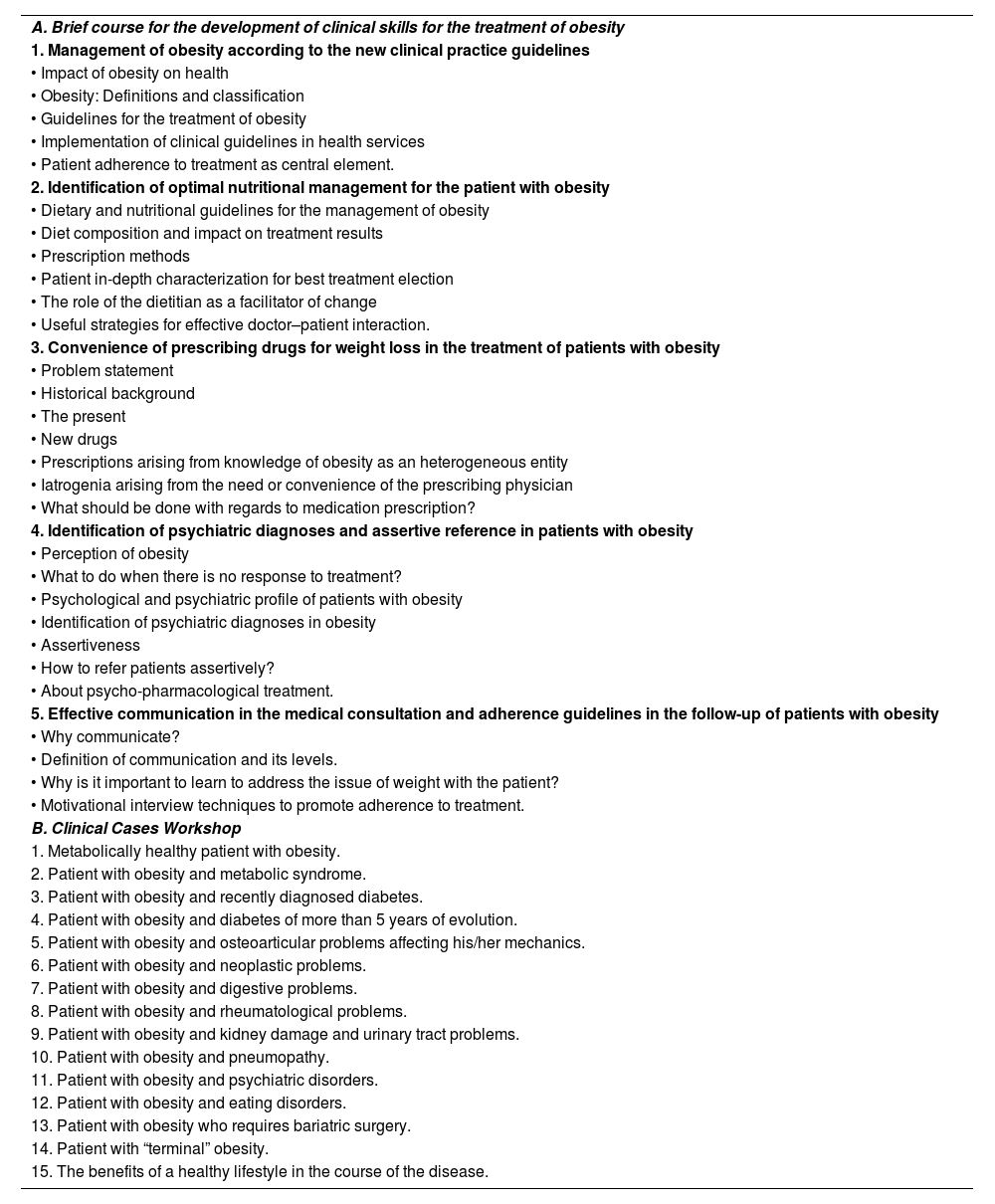

ProposalsThe different specialty programs in which clinical practice is involved should incorporate content on the subject of obesity (including skills to empathically approach patients), its comorbidities, and its interactions with other diseases. It could be in the form of an induction course common to all specialty/subspecialty programs, taught by an interdisciplinary team and should represent the body of knowledge essential to provide the medical students with a basic but solid language that will allow them to continue to incorporate information and experience so that their knowledge grows over time (Table 4).

Curriculum for an immersion course for the development of clinical skills for the treatment of obesity.

| A. Brief course for the development of clinical skills for the treatment of obesity |

| 1. Management of obesity according to the new clinical practice guidelines |

| • Impact of obesity on health |

| • Obesity: Definitions and classification |

| • Guidelines for the treatment of obesity |

| • Implementation of clinical guidelines in health services |

| • Patient adherence to treatment as central element. |

| 2. Identification of optimal nutritional management for the patient with obesity |

| • Dietary and nutritional guidelines for the management of obesity |

| • Diet composition and impact on treatment results |

| • Prescription methods |

| • Patient in-depth characterization for best treatment election |

| • The role of the dietitian as a facilitator of change |

| • Useful strategies for effective doctor–patient interaction. |

| 3. Convenience of prescribing drugs for weight loss in the treatment of patients with obesity |

| • Problem statement |

| • Historical background |

| • The present |

| • New drugs |

| • Prescriptions arising from knowledge of obesity as an heterogeneous entity |

| • Iatrogenia arising from the need or convenience of the prescribing physician |

| • What should be done with regards to medication prescription? |

| 4. Identification of psychiatric diagnoses and assertive reference in patients with obesity |

| • Perception of obesity |

| • What to do when there is no response to treatment? |

| • Psychological and psychiatric profile of patients with obesity |

| • Identification of psychiatric diagnoses in obesity |

| • Assertiveness |

| • How to refer patients assertively? |

| • About psycho-pharmacological treatment. |

| 5. Effective communication in the medical consultation and adherence guidelines in the follow-up of patients with obesity |

| • Why communicate? |

| • Definition of communication and its levels. |

| • Why is it important to learn to address the issue of weight with the patient? |

| • Motivational interview techniques to promote adherence to treatment. |

| B. Clinical Cases Workshop |

| 1. Metabolically healthy patient with obesity. |

| 2. Patient with obesity and metabolic syndrome. |

| 3. Patient with obesity and recently diagnosed diabetes. |

| 4. Patient with obesity and diabetes of more than 5 years of evolution. |

| 5. Patient with obesity and osteoarticular problems affecting his/her mechanics. |

| 6. Patient with obesity and neoplastic problems. |

| 7. Patient with obesity and digestive problems. |

| 8. Patient with obesity and rheumatological problems. |

| 9. Patient with obesity and kidney damage and urinary tract problems. |

| 10. Patient with obesity and pneumopathy. |

| 11. Patient with obesity and psychiatric disorders. |

| 12. Patient with obesity and eating disorders. |

| 13. Patient with obesity who requires bariatric surgery. |

| 14. Patient with “terminal” obesity. |

| 15. The benefits of a healthy lifestyle in the course of the disease. |

- 1.

A first step would be to build the body of knowledge suggested in Table 4 from a multidisciplinary perspective, by physicians (internal medicine specialists, endocrinologists, psychiatrists), dietitians, and psychologists with clinical expertise in the field of obesity. Section A would be prepared, by the member of the multidisciplinary team in charge of the specific topic. For example, topics on nutritional management should be prepared and delivered by dietitians, and pharmacological treatment by physicians, while topics on communication should be delivered by psychologists. Section B entails a set of clinical cases that would be prepared by the multidisciplinary team as a whole in order to give the different topics a comprehensive treatment.

- 2.

Once the body of knowledge is ready, it should be submitted to the University for consensus and finally for approval and inclusion in the PUEM curriculum.

- 3.

The body of knowledge should be submitted to experts in advanced pedagogical techniques for it to be of practical use.

- 4.

A dissemination strategy should be defined; for example, onsite training in qualified multidisciplinary obesity clinics around the country, by videoconference or by online courses. Well designed online courses are practical and can be replicated with ease.

Our proposal should furnish the student with a common language for effectively interacting with the other members of the health team. Practicing physicians know that patients require, among other things, to control their obesity problem in order to have the best response to treatment; however, the lack of tools and self-efficacy in most cases prevents them from conveying this information to their patients and making effective proposals to achieve significant and meaningful results. We believe that with this induction course, physicians could be sensitized to carry out timely and effective diagnoses and treatments and refer patients who require it to specialized clinics in the management of obesity. One should also keep in mind medical specialists who exercise their clinical practice today and were not trained in the study and treatment of obesity. For them, a systematic training in line with the current clinical practice guidelines seems essential.

In conclusion, given the high prevalence of overweight and obesity in Mexico, fostering awareness in students of medical specialties/subspecialties, and training them to acquire knowledge and develop clinical skills is of outmost importance.

Ethical approvalThe study was approved by the IRB (Research Committee and Ethics in Research Committee) of Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán.

Funding sourceFunded in part by Fondo Nestlé para la Nutrición (Nestle Nutrition Fund), Fundación Mexicana para la Salud, México.

Conflicts of interestEPO coordinates the Fondo Nestlé para la Nutrición. LEES, MKH and EGG have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The study was partially financed by Fondo Nestlé para la Nutrición, Fundación Mexicana para la Salud, México.