‘Student engagement in the school’ is offered as one dimension of the ASPIRE-to-Excellence initiative launched in 2012 by AMEE (International Association for Medical Education) to recognize/reward excellence in teaching.

For a school to be awarded in ‘student engagement’ there must be evidence that students contribute to the academic community, take an active role, are consulted, involved and participate in shaping the teaching-learning experience. Four spheres of ‘student engagement’ can be recognized as main criteria namely: school management, education program, academic community and local community.

So far fourteen schools were awarded. Looking at what makes ‘student engagement’ work we learned that ASPIRE is a global phenomenon with features common worldwide, not depending on school resources and not imposing a fixed model of excellence.

ASPIRE is there to prove that excellence in teaching can be assessed. It brought something new because although basic standards for medical education quality were already available the best practices relevant to the schools who wish to achieve excellence in teaching were only defined with ASPIRE in 2012.

ASPIRE is much more than to recognize and reward schools. Its ultimate goal is to have the schools achieving excellence in teaching, independently of having them applying to the award.

La «participación y contribución de los estudiantes al currículo y a la facultad -Students Engagement-» es una dimensión de la iniciativa ASPIRE, lanzada en 2012 por la Asociación Internacional de Educación Médica (AMEE), para reconocer/premiar la excelencia educativa.

Para que una facultad sea premiada por la «participación de sus estudiantes» deben existir evidencias de que ellos contribuyen a la comunidad académica, participan activamente en la toma de decisiones, son consultados y se implican en dar forma a la experiencia enseñanza-aprendizaje. Cuatro esferas de «participación y contribución de los estudiantes» son reconocidas como criterios principales: gestión de la facultad, programa educativo, comunidad académica y comunidad local.

Hasta el momento, 14 facultades has sido galardonadas por la «participación de sus estudiantes» y hemos aprendido que ASPIRE es un fenómeno global con características comunes a nivel mundial, no depende de los recursos de la facultad y no impone un modelo fijo de excelencia.

ASPIRE existe para demostrar que la excelencia docente puede evaluarse. Esto es algo nuevo, ya que, aun estando disponibles estándares básicos para la calidad de la educación médica, únicamente ASPIRE ha conseguido definir las mejores prácticas, trascendentales para facultades que desean alcanzar la excelencia docente.

ASPIRE va mucho más allá de reconocer y premiar facultades. Su objetivo principal es hacer que las facultades alcancen la excelencia docente, independientemente de que estén solicitando el reconocimiento.

This manuscript focuses on excellence in terms of ‘student engagement in the school’, one of the three initial dimensions of the ASPIRE initiative1 launched by AMEE (www.amee.org) at the 2012 Conference in Lyon to recognize and reward excellence in teaching, for the first time.

ASPIRE was introduced in a time where the medical education concern was to have in place a mechanism for quality improvement in medical education worldwide to be used by institutions, organizations and national authorities responsible for medical education.2 This was the context when in March 2003 the Trilogy of the Global Standards2 for quality development of Medical Education was published at the WFME (World Federation for Medical Education) Conference arranged in cooperation with WHO, UNESCO, WMA, the University of Copenhagen and Lund University. At that time the purpose was to agree on medical education standards to ensure that the competencies of medical doctors are globally applicable, transparent and transferable.2

Less than 10 years after the global standards were launched, medical education was confronted with a more demanding challenge namely the need to go beyond the standards to recognize excellence in teaching because so far excellence had been judged entirely on the basis of research. The problem was that over the past decade the move has been to pay increasing attention to university rankings based mainly on research criteria with no attention paid to teaching.

In 2013, after a pilot process the ASPIRE initiative was successfully implemented to recognize the importance of teaching alongside research as the mission of a medical school.3,4 Since 2015 ASPIRE is also recognizing excellence in higher education from dental and veterinary schools.

If I feel privileged for having attended both conferences where such important initiatives were launched I must say the ASPIRE initiative made me realize that a giant step had been taken to improve medical education. The launch of ASPIRE was indeed a turning point accompanying what was done worldwide in other areas namely in sports, arts, literature, etc. to recognize excellence.

ASPIRE has the potential to revolutionize medical education worldwide with the schools aiming to achieve excellence as part of their mission.

Defining ‘student engagement’ is not easy because ‘several definitions are given and each of the approaches to student engagement has strengths and limitations’.1 Kahu in 2013 presents a conceptual framework that seeks to combine all elements and present student engagement as a ‘psycho-social process, influenced by institutional and personal factors, and embedded within a wider social context, integrates the social-cultural perspective with the psychological and behavioural’.5

For a school to be regarded as achieving excellence in student engagement in a medical, dental or veterinary school, there must be evidence that students contribute to the academic community and that they take an active role and are consulted, involved and participate in shaping the teaching and learning experience.1

The importance of student engagement in the schoolMuch has been said on the importance of having students engaged in their schools. Two arguments deserve to be highlighted:

- •

Today medical students, Doctors of the future

‘Today Medical Students, Doctors of the Future’ was the highlight promoting the last 25th General Assembly of EMSA (European Medical Students’ Association) hold in Berlin in September 2015 under the topic of ‘Doctors of the future’.

This argument justifies the importance of having student engagement in the school as one of the ASPIRE initial dimensions: to prepare students for their future role as doctors, we must engage them in the curriculum and in the school from the first year of their studies. We must have students assuming an active position in the school by intervening and being partners in the decisions concerning their teaching-learning process. The objective is to make students aware of the need to move from passive learners to active future tomorrow's doctors from the very beginning of their education.

The background for this argument dates back to the ancient general concept of ‘learning through experience’ from around 350 BC, when Aristotle wrote in the Nichomachean Ethics ‘for the things we have to learn before we can do them, we learn by doing them’. This approach evolved to an articulated educational theory with David Kolb who in 1984 developed the modern concept of ‘experiential learning’.6

In the context of ASPIRE, student engagement in the school’ implies to have the students engaged with the management of the school, the delivery of teaching and assessment, the academic and local communities as well as the service delivery1

- •

Transformative Education as the third level of educational programs

In 2010 the Lancet report put forward a series of instructional and institutional reforms to achieve what they called the ‘third-generation reforms’.7

‘Transformative learning is the highest of three successive levels, moving from informative to formative to transformative learning. Informative learning is about acquiring knowledge and skills (to produce experts). Formative learning is about socializing students around values (to produce professionals). Transformative learning is about developing leadership attributes (to produce enlightened change agents of society’. The Lancet goes on to call for a global social movement of all stakeholders that can propel action in the light of this vision and these recommendations to promote a new century of transformative professional education.7

If we aim to have doctors acting as enlightened leaders engaged in transforming society we must have students as enlightened leaders engaged in transforming their own school. The goal is simple, using the school as a privileged stage to prepare today students for their future role as society enlightened change agents.

Setting the task of establishing and testing criteriaDetailed information on the establishing and testing criteria is given at ASPIRE website.1 A short summary is presented below.

It is important to remember that while recognition for exemplary status is an understandable goal for each applicant, the underlying reason for the existence of ASPIRE is to promote the development of excellence in medical education. This includes the establishment of aspirational goals, criteria for excellence and a peer review process.1

After decision was taken to move forward the ASPIRE – International Recognition of excellence in education, an International Board was set up to think on how to create a system to recognize excellence in teaching. Being aware of the difficulty of having a comprehensive set of criteria to embrace different cultures, societies and environments the Board realized it could not be too prescriptive when defining criteria.1

The ASPIRE Award for excellence in student engagement recognizes the different approaches and means of assessing student engagement and sought to synthesize them in a way that can be operationalized and assessed. It was agreed that for a school to be regarded as achieving excellence in student engagement, in a medical, dental or veterinary school, there must be evidence that students contribute to the academic community and that they take an active role and are consulted, involved and participate in shaping the teaching and learning experience. Four spheres of engagement can be recognized as main criteria:

- 1.

Student engagement with the management of the school, including matters of policy and the mission and vision of the school. (Student engagement with the structures and processes.)

- 2.

Student engagement in the provision of the school's education program. (Student engagement with the delivery of teaching and assessment.)

- 3.

Student engagement in the academic community. (Student's engagement in the school's research program and participation in meetings.)

- 4.

Student engagement in the local community and the service delivery.1

For each sphere, more detailed indicators were described for each criterion and submitted to AMEE members and other educational communities for validation. Feedback from this process was taken into account to define final criteria and sub-criteria which are presented in Table 1.

Student engagement in the school. ASPIRE criteria and sub-criteria.

| CRITERION 1. Related to student engagement with management of the school, including matters of policy and the mission and vision of the school |

| (Student engagement with the structures and processes) |

| 1.1. Students have been involved in the development of the school's vision and mission |

| 1.2. Students are represented on school committees |

| 1.3. Students are involved in the establishment of policy statements or guidelines |

| 1.4. Students are involved in the accreditation process for the school |

| 1.5. Students have a management/leadership role in relation to elements of the curriculum |

| 1.6. Students’ views are taken into account in decisions about faculty (staff) promotion |

| 1.7. Students play an active part in faculty (staff) development activities |

| CRITERION 2. Student Engagement in the provision of the school's education program |

| (Student engagement with the delivery of teaching and assessment) |

| 2.1. Students evaluate the curriculum and teaching and learning processes |

| 2.2. Feedback from the student body is taken into account in curriculum development |

| 2.3. Students participate as active learners with responsibility for their own learning |

| 2.4. Students are involved formally and/or informally in peer teaching |

| 2.5. Students are engaged in the development of learning resources for use by other students |

| 2.6. Students provide a supportive or mentor role for other students |

| 2.7. Students are encouraged to assess their own competence |

| 2.8. Students engaged in peer assessment |

| CRITERION 3. Engagement in the academic community |

| (Student's engagement in the school's research program and participation in meetings) |

| 3.1. Students are engaged in school research projects carried out by faculty members |

| 3.2. Students are supported in their participation at local, regional or international medical, dental, veterinary and health professions education meetings |

| CRITERION 4. Engagement in the local community and service delivery |

| 4.1. Students are involved in local community projects |

| 4.2. Students participate in the delivery of local healthcare services |

| 4.3. Students participate in healthcare delivery during electives/attachments overseas |

| 4.4. Students engage with arranged extracurricular activities |

A pilot phase was initiated with schools submitting their proposals with no fee requested. It was agreed that those schools could apply the year after again with no payment and doing so they are in a better position than the schools submitting for the first time because they may benefit from feedback obtained during the pilot phase.

The ASPIRE program utilizes peer reviewers from around the world who have distinguished themselves for their experience and understanding of student engagement.

Each application is sent to three independent reviewers who review a school's application and separately record their observations. They then interact with each other and arrive at a Review Team Consensus Report and recommendation related to both individual components of the application and an overall recommendation of whether to award the ASPIRE recognition.

This recommendation is then reviewed by the ASPIRE Panel on Student engagement, and then by the ASPIRE Board and only then is the final decision made for each of the applications.

The notion of excellence embodies the active engagement with scholarship and a desire to seek continuous improvement in the area of student engagement. It is recognized that cultural, social and other issues are likely to have an influence on the engagement of students in a school and that how student engagement manifests itself will vary from school to school.

It was agreed from the beginning that schools could be awarded if they are considered excellent in what was defined as ‘required criteria’ i.e. the areas considered of major importance (such as curriculum inputs and evaluation of the curriculum, to name a few) even if they are not excellent in all spheres and all indicators. To facilitate the school (when submitting the form) and the role of the reviewers the required criteria considered of crucial importance are highlighted in the submission form.

ASPIRE best practices in student engagement in the schoolFourteen schools were recognized by ASPIRE during past four years:

- •

In 2013, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine (USA), Aga Khan University (Pakistan), University of Maribor (Slovenia), International Medical University (Malaysia), University of Western Australia, Faculty of Medicine Dentistry & Health Sciences (Australia) and University of Minho (Portugal),

- •

In 2014, the University of Southampton (UK),

- •

In 2015, the Charité – Universitätsmedizin (Germany), University of Leeds School of Medicine (UK), Utrecht University, Faculty of Medicine (The Netherlands), Uppsala University, School of Medicine (Sweden), Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry (Canada) and Chulalongkorn University, Faculty of Medicine (Thailand),

- •

In 2016 the School of Veterinary Medicine & Science, University of Nottingham (UK).

Each school found their own way to achieve excellence. Some examples of ASPIRE best practices extracted from winner submissions are presented in Table 2.

Student engagement in the school. Examples of ASPIRE best practices (extracted from school submissions).

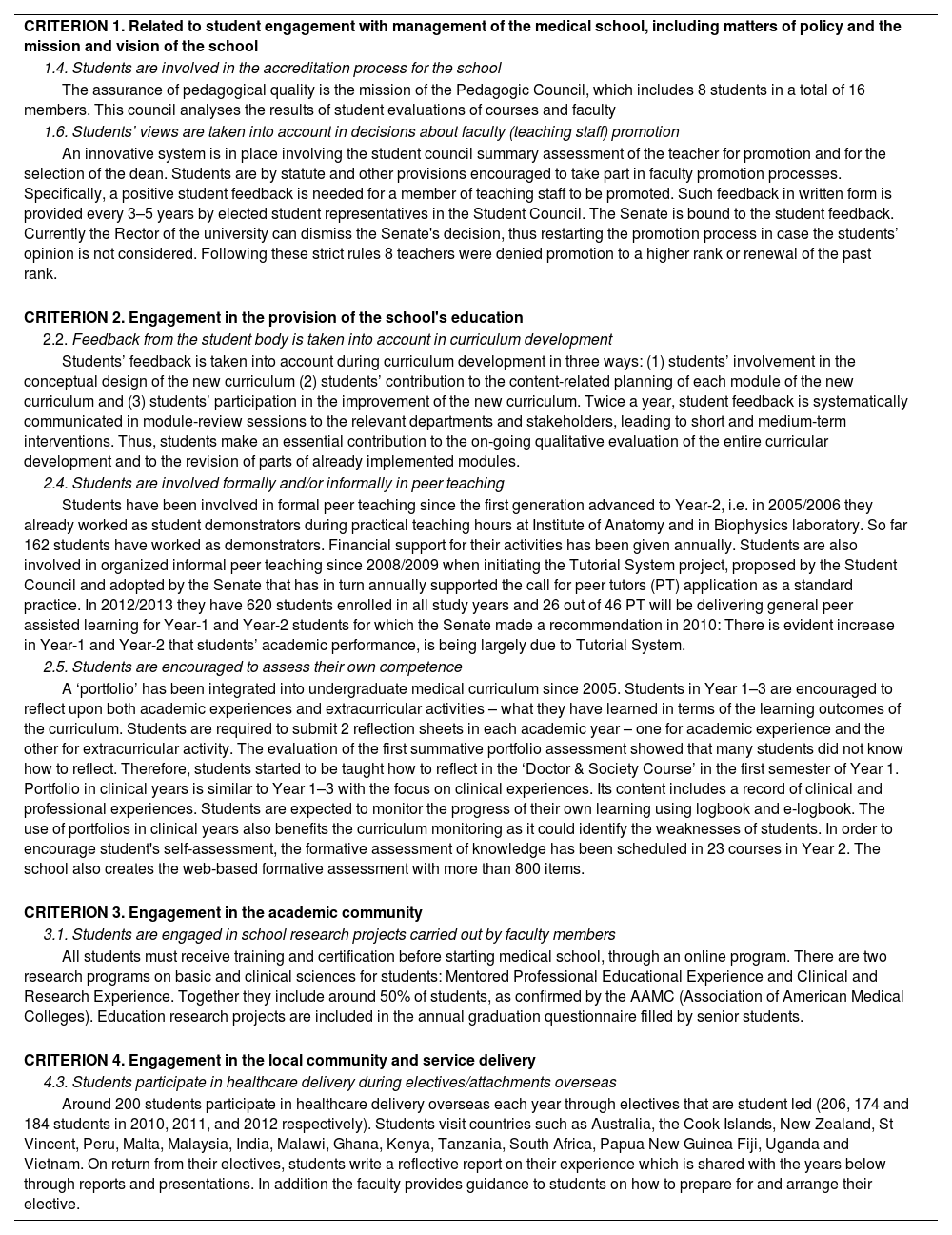

| CRITERION 1. Related to student engagement with management of the medical school, including matters of policy and the mission and vision of the school |

| 1.4. Students are involved in the accreditation process for the school |

| The assurance of pedagogical quality is the mission of the Pedagogic Council, which includes 8 students in a total of 16 members. This council analyses the results of student evaluations of courses and faculty |

| 1.6. Students’ views are taken into account in decisions about faculty (teaching staff) promotion |

| An innovative system is in place involving the student council summary assessment of the teacher for promotion and for the selection of the dean. Students are by statute and other provisions encouraged to take part in faculty promotion processes. Specifically, a positive student feedback is needed for a member of teaching staff to be promoted. Such feedback in written form is provided every 3–5 years by elected student representatives in the Student Council. The Senate is bound to the student feedback. Currently the Rector of the university can dismiss the Senate's decision, thus restarting the promotion process in case the students’ opinion is not considered. Following these strict rules 8 teachers were denied promotion to a higher rank or renewal of the past rank. |

| CRITERION 2. Engagement in the provision of the school's education |

| 2.2. Feedback from the student body is taken into account in curriculum development |

| Students’ feedback is taken into account during curriculum development in three ways: (1) students’ involvement in the conceptual design of the new curriculum (2) students’ contribution to the content-related planning of each module of the new curriculum and (3) students’ participation in the improvement of the new curriculum. Twice a year, student feedback is systematically communicated in module-review sessions to the relevant departments and stakeholders, leading to short and medium-term interventions. Thus, students make an essential contribution to the on-going qualitative evaluation of the entire curricular development and to the revision of parts of already implemented modules. |

| 2.4. Students are involved formally and/or informally in peer teaching |

| Students have been involved in formal peer teaching since the first generation advanced to Year-2, i.e. in 2005/2006 they already worked as student demonstrators during practical teaching hours at Institute of Anatomy and in Biophysics laboratory. So far 162 students have worked as demonstrators. Financial support for their activities has been given annually. Students are also involved in organized informal peer teaching since 2008/2009 when initiating the Tutorial System project, proposed by the Student Council and adopted by the Senate that has in turn annually supported the call for peer tutors (PT) application as a standard practice. In 2012/2013 they have 620 students enrolled in all study years and 26 out of 46 PT will be delivering general peer assisted learning for Year-1 and Year-2 students for which the Senate made a recommendation in 2010: There is evident increase in Year-1 and Year-2 that students’ academic performance, is being largely due to Tutorial System. |

| 2.5. Students are encouraged to assess their own competence |

| A ‘portfolio’ has been integrated into undergraduate medical curriculum since 2005. Students in Year 1–3 are encouraged to reflect upon both academic experiences and extracurricular activities – what they have learned in terms of the learning outcomes of the curriculum. Students are required to submit 2 reflection sheets in each academic year – one for academic experience and the other for extracurricular activity. The evaluation of the first summative portfolio assessment showed that many students did not know how to reflect. Therefore, students started to be taught how to reflect in the ‘Doctor & Society Course’ in the first semester of Year 1. Portfolio in clinical years is similar to Year 1–3 with the focus on clinical experiences. Its content includes a record of clinical and professional experiences. Students are expected to monitor the progress of their own learning using logbook and e-logbook. The use of portfolios in clinical years also benefits the curriculum monitoring as it could identify the weaknesses of students. In order to encourage student's self-assessment, the formative assessment of knowledge has been scheduled in 23 courses in Year 2. The school also creates the web-based formative assessment with more than 800 items. |

| CRITERION 3. Engagement in the academic community |

| 3.1. Students are engaged in school research projects carried out by faculty members |

| All students must receive training and certification before starting medical school, through an online program. There are two research programs on basic and clinical sciences for students: Mentored Professional Educational Experience and Clinical and Research Experience. Together they include around 50% of students, as confirmed by the AAMC (Association of American Medical Colleges). Education research projects are included in the annual graduation questionnaire filled by senior students. |

| CRITERION 4. Engagement in the local community and service delivery |

| 4.3. Students participate in healthcare delivery during electives/attachments overseas |

| Around 200 students participate in healthcare delivery overseas each year through electives that are student led (206, 174 and 184 students in 2010, 2011, and 2012 respectively). Students visit countries such as Australia, the Cook Islands, New Zealand, St Vincent, Peru, Malta, Malaysia, India, Malawi, Ghana, Kenya, Tanzania, South Africa, Papua New Guinea Fiji, Uganda and Vietnam. On return from their electives, students write a reflective report on their experience which is shared with the years below through reports and presentations. In addition the faculty provides guidance to students on how to prepare for and arrange their elective. |

Feedback received so far from the stakeholders involved in the ASPIRE initiative is very positive which does not mean there are no aspects to be improved.

The difficulty to define excellence in student engagement based on the school performance in each criterion is among the aspects to be improved. For reviewers it is a question of weighing the areas where evidence was achieved versus the ones where evidence was not found. Despite the definition of ‘required areas’ the final decision is sometimes hard to be reached.

ASPIRE is particularly attentive to this and other aspects when seeking for improvement. This is why in addition to a full morning session dedicated to the Board and Panel meetings during the AMEE 2016 Conference a full day meeting is scheduled before the AMEE Conference in Barcelona to identify priority actions for improvement.

Based on the progress so far the following lessons were learnt in terms of what appears to make student engagement work:

- •

ASPIRE features are common worldwide, i.e. ASPIRE is a global phenomenon. The 14 ASPIRE winners to date, are a good example of ASPIRE as a ‘global phenomenon’ with Australia, Canada, Germany, Malaysia, Pakistan, Portugal, Slovenia, Sweden, Thailand, The Netherlands, UK and USA being the countries where one or more schools were recognized.

- •

ASPIRE recognition does not depend on school resources. ASPIRE has rewarded schools independently of their financial situation showing that it is possible to achieve excellence even with more limited resources. The way in which institutions demonstrate cost effectiveness and context appropriateness is taken into account when the submissions are reviewed.

- •

ASPIRE is not imposing a fixed model of excellence. If recognition in above listed criteria is needed for a school to be recognized for an ASPIRE award what is extraordinary is the fact that each school can find its own way to meet each criterion and therefore achieve excellence and be recognized by ASPIRE. In other words ASPIRE does not demand the schools to follow a fixed matrix for excellence; on the contrary choosing the way to exercise excellence in student engagement is a prerogative of each medical school.

These features are no doubt the beauty of ASPIRE and what makes the reviewers feel inspired and enthusiastic throughout the whole process of assessing the submissions: a really exciting and challenging task.

Conclusions- •

The ASPIRE initiative is there to prove that excellence in teaching can be assessed, namely in terms of student engagement in the school. Criteria are available to judge the reported evidence (what the schools say they have done) versus provided evidence (documents to support what is reported).

- •

The ASPIRE initiative is much more than an initiative to recognize and reward schools. ASPIRE has a stimulating effect not only in schools, motivating and raising their interest for achieving excellence but also in students, motivating and making them aware of their potential engagement roles in their schools

- •

ASPIRE is offering schools and students the criteria. They may follow to achieve excellence. Then it is up to them to decide how each criterion will be implemented.

- •

ASPIRE brought something new in terms of excellence in teaching. Before the ASPIRE initiative basic standards for medical education quality were available but the best practices relevant to the schools who wish to achieve excellence in teaching were only defined by ASPIRE.

- •

ASPIRE's ultimate goal is to have the schools achieving excellence in teaching, independently of having them applying (or not) to the ASPIRE award. When ASPIRE was launched the aim was not only to recognize and reward the schools for their excellence in teaching but also to offer criteria and role models to those schools who wish to improve. This is one area where ASPIRE must invest namely in the dissemination of and easy access to concrete examples of excellence to guide other schools that wish to move there.

- •

ASPIRE's major aim cannot be achieved just with a top-down process. A bottom-up process is crucial in each school for this huge task and this is why we take this opportunity to invite you – teachers, educators, administratives, students and all other stakeholders to join us to disseminate ASPIRE criteria and motivate schools to achieve excellence in medical, dental and veterinary education. ASPIRE initiative will progress to achieve excellence in student engagement worldwide.

The author reports no conflicts of interest. The author alone is responsible for the content and writing of the article.

The author wishes to warmly thank Prof. Maria Rosa Fenoll-Brunet and Prof. Ronald M. Harden for their invaluable comments concerning this manuscript.