Television medical dramas enjoy great popularity among the general public and university students. These dramas have been used to illustrate important aspects of medical training (doctor–patient relationships, professionalism, ethical conflicts), but their usefulness for discussing the use of drugs in medical care remains unexplored. We analyzed pharmacological issues in House, M.D. to determine their potential usefulness in teaching clinical pharmacology.

Material and methodsTwo investigators, blind to each other's responses, reviewed each of the 22 episodes of the first season of House, M.D., recording the main and secondary topics dealt with as well as the drugs portrayed and rating the episode's interest for teaching clinical pharmacology (High/Medium/Low). Discordant ratings were settled by a third (or fourth, if necessary) investigator.

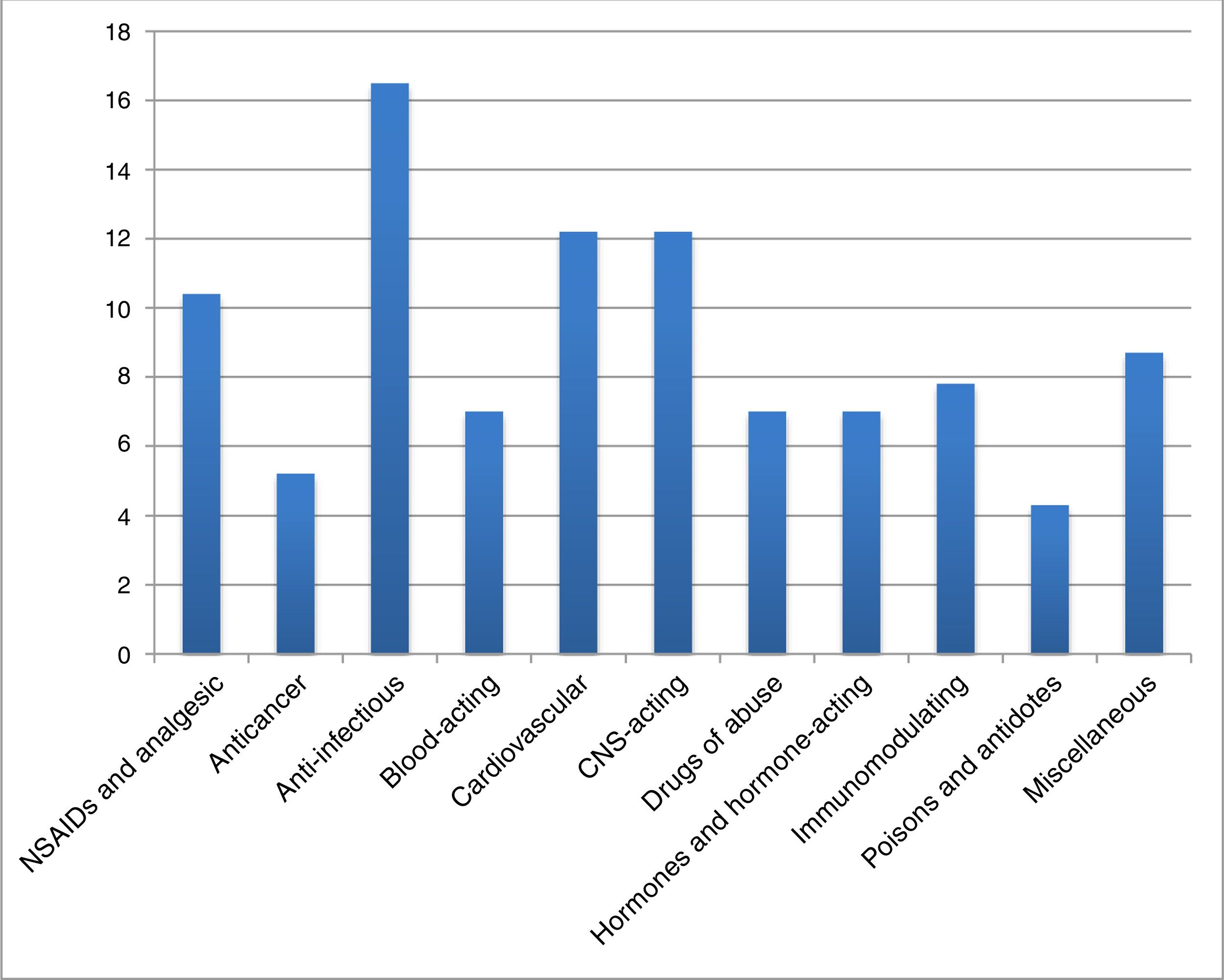

ResultsMost episodes included information on drugs; in six, pharmacologic issues were the main topics. The episodes dealt with 115 drugs, mainly anti-infective (16.5%), cardiovascular (12.2%), CNS-acting (12.2%), and analgesic or anti-inflammatory (12.2%) drugs. Five episodes were considered very useful for teaching clinical pharmacology.

DiscussionThe episodes of the first season of House, M.D. contained frequent references to drug treatment and pharmacological issues; in a few episodes, the main topic was related with clinical pharmacology. Before medical dramas are recommended as a regular teaching tool, their pedagogical efficacy should be tested empirically.

Las series médicas de televisión disfrutan de gran popularidad entre los estudiantes universitarios, y se han empleado para ilustrar aspectos importantes de la educación médica (relación médico-paciente, profesionalismo, conflictos éticos). Su utilidad para debatir el empleo de medicamentos en la práctica médica no se ha evaluado. En el presente estudio analizamos los temas farmacológicos presentes en House, M.D. para establecer su interés potencial en la docencia de la farmacología clínica.

Material y métodosDos investigadores, desconocedores de las respuestas mutuas, revisaron los 22 episodios de la primera temporada de House, M.D., y registraron los temas principales y secundarios de cada episodio, así como los fármacos empleados. Asimismo, puntuaron su interés para la docencia de la farmacología clínica (alto/medio/bajo). Cuando existía discordancia, un tercer evaluador (y un cuarto, si era necesario) establecía la decisión final.

ResultadosLa mayoría de los capítulos contenían información de medicamentos; en 6 los temas farmacológicos constituían el principal elemento argumental. Los episodios refirieron 115 fármacos, principalmente antiinfecciosos (16,5%), cardiovasculares (12,2%), neuropsicofármacos (12,2%) y analgésicos o antiinflamatorios (12,2%). Se consideró que 5 episodios podrían tener utilidad docente alta.

DiscusiónLos episodios de la primera temporada de House, M.D. contenían referencias frecuentes a medicamentos y a temas farmacológicos. En un número reducido de episodios, el argumento principal se vinculaba a la farmacología clínica. Antes de que pueda recomendarse su empleo en docencia, debe evaluarse empíricamente su eficacia pedagógica.

Since the beginning of motion pictures, the plots of feature films have often involved medicine. The diverse reasons for using medicine in fiction include the social importance of disease and suffering as human experiences, the impact of medical discoveries on health and social progress in modern societies, and the general perception of physicians as distinguished professionals.1,2 In recent decades, feature films have been increasingly used in teaching medical3,4 and nursing students5 as well as in training residents in different specialties.2,6 Various authors have proposed different ways to improve the effectiveness of audiovisual fiction in medical education,7,8 and some authors have recently reviewed the portrayal of medical matters in television series.9,10

Television series might have some advantages over feature films. First, every episode is shorter than a feature film and usually explains a full story. Second, each episode has a different plot, so it increases the likelihood of finding material appropriate for the purpose of the class. Third, many series can be used, so there is a wide field to explore. Various authors have recently suggested that medical dramas could be used as a teaching tool.11,12 Some studies have dealt with their usefulness for analyzing students’ perceptions on medical professionalism and ethics13–17 and for teaching psychotherapeutic18 and communication techniques.19 However, the lack of published experiences on the actual value of medical series in improving learning limits their use.

Since home television became available more than sixty years ago, series have often portrayed physicians and medicine.20 Early medical series such as Dr. Kildare (1961–1966) and Marcus Welby, M.D. (1969–1976) were very popular. More recently, Chicago Hope, ER, Grey's Anatomy, and Scrubs have been very successful, especially among students of the health sciences.21,22 Various authors have analyzed this popularity.23–30 Undoubtedly, one of the most popular medical dramas has been House, M.D., which was broadcast for eight consecutive seasons (2004–2012).

House, M.D. has many elements of interest for the lay public as well as for health professionals and health sciences students.22 The main character, Gregory House, is a brilliant physician who is interested only in the scientific side of the medical profession. He distrusts patients and hates working under the hospital rules. He became addicted to opioid analgesics after taking them regularly for chronic pain. House's diagnostic reasoning is comparable to the method of reasoning Sherlock Holmes used to solve crimes, and some authors have suggested there is a close relationship between the logics of clinical reasoning and crime solving.31 Dr. House's continuous questioning of the members of his team during the diagnostic process also brings to mind Socratic and problem-based learning methods. This medical drama illustrates a model of doctor–patient relationship that rejects patients’ autonomy in taking medical decisions about their own health,32 and Wicclair33 suggested that analyzing this approach to the relationship might be useful in teaching ethics to medical students.

As feature films have been successfully used in the teaching of pharmacology,34,35 we hypothesized that television series could also be used for this purpose. First we aimed to determine whether the episodes contain enough material related to pharmacology issues to justify this approach; this is a very important issue, as the potential value of the episode is highly dependent on its relevance.29

We present here the results of a content analysis of the first season of House, M.D. The analysis aimed to answer two questions: (1) what types of pharmacological topics are portrayed? And (2) can the episodes be useful for teaching clinical pharmacology? A preliminary analysis of this study was published elsewhere.36

MethodsThe medical drama: House, M.D.This series created by David Shore ran on the Fox network comprising a total of 177 episodes in eight seasons. The main character is Gregory House (played by Hugh Laurie), who chairs a diagnostic team in the fictional Princeton-Plainsboro Teaching Hospital in New Jersey. Inspired by Dr. Lisa Sanders’ New York Times Magazine column “Diagnosis”, Paul Attanasio came up with the idea for a medical procedural drama, and Shore created the characters. The first season introduced other important characters, including Dr. Lisa Cuddy, the hospital administrator (played by Lisa Edelstein), Dr. James Wilson, an oncologist and House's friend (played by Robert Sean Leonard), and the members of House's unit: Dr. Robert Chase (played by Jesse Spencer), Dr. Allison Cameron (played by Jennifer Morrison), and Dr. Eric Foreman (played by Omar Epps). The series achieved large audiences and critical acclaim.

The present study analyzed the 22 episodes in first season, which aired from November 16, 2004 to May 24, 2005.

Study protocolInvestigators who reviewed the episodes hold a PhD in pharmacology and/or were board certified in clinical pharmacology, and had experience of several years of teaching these disciplines to medical students. Two of them, blind to each other's responses, reviewed one episode and collected the following information:

- •

Topics:

- ∘

Main topic: defined as the topic that focused most attention of the chapter; exceptionally, more than one topic could be considered.

- ∘

Secondary topics: any other medical topic included in the chapter.

- ∘

Drugs: identified by their generic names and classified in their pharmacological group.

- •

Interest for the teaching of clinical pharmacology, scored as follows:

- ∘

High: when the main topic depicted important concepts in clinical pharmacology or the use of drugs in clinical practice, for example, drug abuse as a cause of disease, adverse effects that explained the clinical picture, or unexpected poisoning by chemicals.

- ∘

Medium: when the secondary topics depicted important concepts in clinical pharmacology or the use of drugs in clinical practice, for example, occurrence of important adverse reactions or therapeutic efficacy.

- ∘

Low: when important concepts in clinical pharmacology or the use of drugs in clinical practice were not depicted or depicted only cursorily.

After all chapters had been reviewed, the results were analyzed as follows:

- •

Main topic: the topic was included when both evaluators agreed.

- •

Secondary topics: given the wide diversity, all topics chosen by at least one evaluator were included.

- •

Drugs: all drugs listed by at least one evaluator were included.

- •

Interest for the teaching of clinical pharmacology: when both evaluators rated the interest of the episode High, Medium, or Low, that rating was final. When the two evaluators gave discordant ratings, a third evaluator, blind to the others’ ratings, rated the interest. If the third evaluator's rating was concordant with one of the first two evaluator's rating, the concordant rating was considered final. If the third evaluator's rating was discordant with those of the first two evaluators, a fourth evaluator rated the interest and thus decided the final rating. The third and fourth evaluator were full professors of Pharmacology and Clinical Pharmacology. To evaluate the interest of each episode, the correctness of the information provided was always considered.

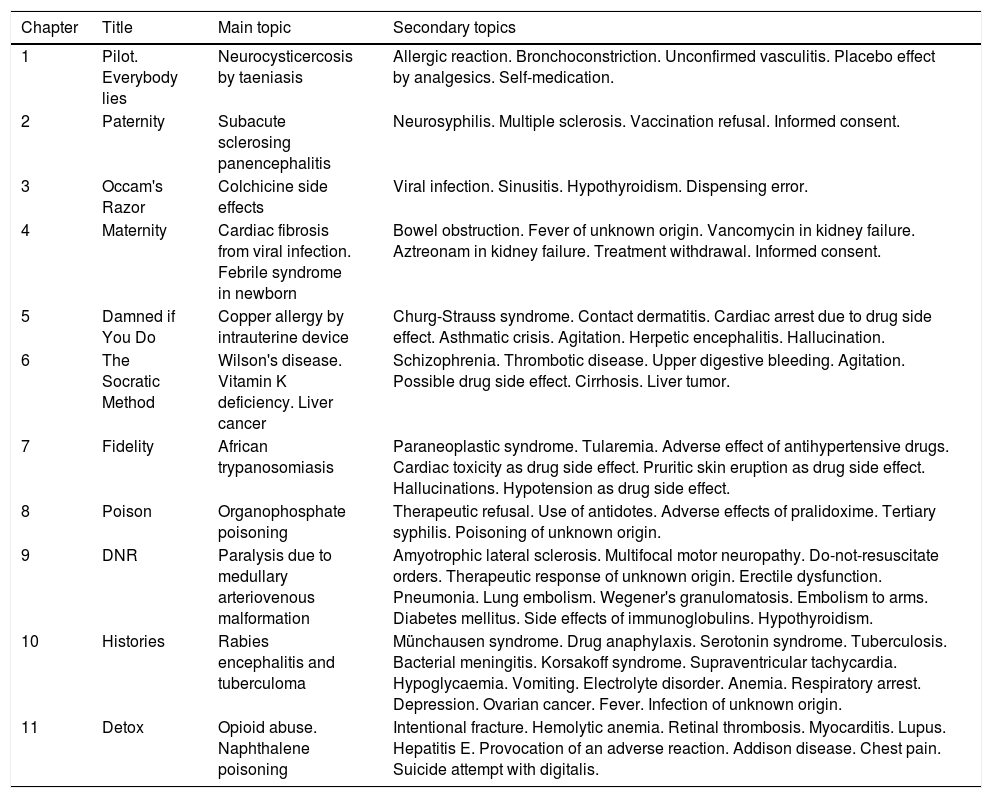

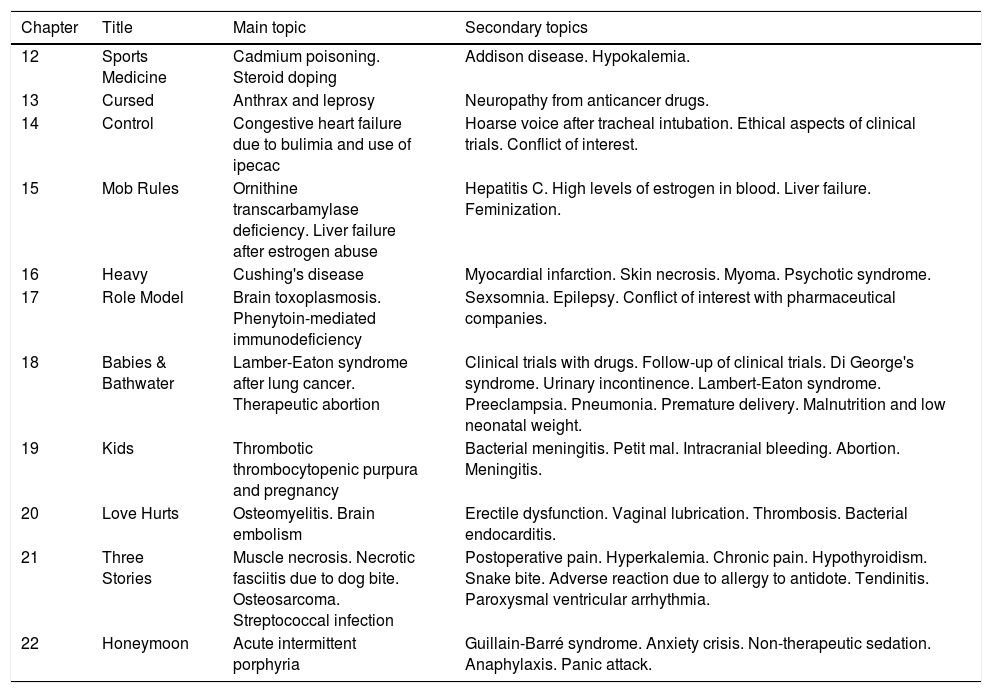

Tables 1 and 2 describe the main and secondary topics identified for each episode. Only one major topic was identified for 13 episodes; two major topics were identified for 7, three major topics for 1, and four major topics for 1 (#21). A clinical pharmacology issue was the sole main topic in three episodes (#3 colchicine side effects, #8 organophosphate poisoning, and #14 ipecac cardiomyopathy) and one of the main topics in another three (#11 opioid abuse, #12 anabolic steroid doping, and #15 estrogen abuse).

Main and secondary topics portrayed in episodes 1–11 in the first season of House, M.D.

| Chapter | Title | Main topic | Secondary topics |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pilot. Everybody lies | Neurocysticercosis by taeniasis | Allergic reaction. Bronchoconstriction. Unconfirmed vasculitis. Placebo effect by analgesics. Self-medication. |

| 2 | Paternity | Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis | Neurosyphilis. Multiple sclerosis. Vaccination refusal. Informed consent. |

| 3 | Occam's Razor | Colchicine side effects | Viral infection. Sinusitis. Hypothyroidism. Dispensing error. |

| 4 | Maternity | Cardiac fibrosis from viral infection. Febrile syndrome in newborn | Bowel obstruction. Fever of unknown origin. Vancomycin in kidney failure. Aztreonam in kidney failure. Treatment withdrawal. Informed consent. |

| 5 | Damned if You Do | Copper allergy by intrauterine device | Churg-Strauss syndrome. Contact dermatitis. Cardiac arrest due to drug side effect. Asthmatic crisis. Agitation. Herpetic encephalitis. Hallucination. |

| 6 | The Socratic Method | Wilson's disease. Vitamin K deficiency. Liver cancer | Schizophrenia. Thrombotic disease. Upper digestive bleeding. Agitation. Possible drug side effect. Cirrhosis. Liver tumor. |

| 7 | Fidelity | African trypanosomiasis | Paraneoplastic syndrome. Tularemia. Adverse effect of antihypertensive drugs. Cardiac toxicity as drug side effect. Pruritic skin eruption as drug side effect. Hallucinations. Hypotension as drug side effect. |

| 8 | Poison | Organophosphate poisoning | Therapeutic refusal. Use of antidotes. Adverse effects of pralidoxime. Tertiary syphilis. Poisoning of unknown origin. |

| 9 | DNR | Paralysis due to medullary arteriovenous malformation | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Multifocal motor neuropathy. Do-not-resuscitate orders. Therapeutic response of unknown origin. Erectile dysfunction. Pneumonia. Lung embolism. Wegener's granulomatosis. Embolism to arms. Diabetes mellitus. Side effects of immunoglobulins. Hypothyroidism. |

| 10 | Histories | Rabies encephalitis and tuberculoma | Münchausen syndrome. Drug anaphylaxis. Serotonin syndrome. Tuberculosis. Bacterial meningitis. Korsakoff syndrome. Supraventricular tachycardia. Hypoglycaemia. Vomiting. Electrolyte disorder. Anemia. Respiratory arrest. Depression. Ovarian cancer. Fever. Infection of unknown origin. |

| 11 | Detox | Opioid abuse. Naphthalene poisoning | Intentional fracture. Hemolytic anemia. Retinal thrombosis. Myocarditis. Lupus. Hepatitis E. Provocation of an adverse reaction. Addison disease. Chest pain. Suicide attempt with digitalis. |

Main and secondary topics portrayed in episodes 12–22 in the first season of House M.D.

| Chapter | Title | Main topic | Secondary topics |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | Sports Medicine | Cadmium poisoning. Steroid doping | Addison disease. Hypokalemia. |

| 13 | Cursed | Anthrax and leprosy | Neuropathy from anticancer drugs. |

| 14 | Control | Congestive heart failure due to bulimia and use of ipecac | Hoarse voice after tracheal intubation. Ethical aspects of clinical trials. Conflict of interest. |

| 15 | Mob Rules | Ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. Liver failure after estrogen abuse | Hepatitis C. High levels of estrogen in blood. Liver failure. Feminization. |

| 16 | Heavy | Cushing's disease | Myocardial infarction. Skin necrosis. Myoma. Psychotic syndrome. |

| 17 | Role Model | Brain toxoplasmosis. Phenytoin-mediated immunodeficiency | Sexsomnia. Epilepsy. Conflict of interest with pharmaceutical companies. |

| 18 | Babies & Bathwater | Lamber-Eaton syndrome after lung cancer. Therapeutic abortion | Clinical trials with drugs. Follow-up of clinical trials. Di George's syndrome. Urinary incontinence. Lambert-Eaton syndrome. Preeclampsia. Pneumonia. Premature delivery. Malnutrition and low neonatal weight. |

| 19 | Kids | Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and pregnancy | Bacterial meningitis. Petit mal. Intracranial bleeding. Abortion. Meningitis. |

| 20 | Love Hurts | Osteomyelitis. Brain embolism | Erectile dysfunction. Vaginal lubrication. Thrombosis. Bacterial endocarditis. |

| 21 | Three Stories | Muscle necrosis. Necrotic fasciitis due to dog bite. Osteosarcoma. Streptococcal infection | Postoperative pain. Hyperkalemia. Chronic pain. Hypothyroidism. Snake bite. Adverse reaction due to allergy to antidote. Tendinitis. Paroxysmal ventricular arrhythmia. |

| 22 | Honeymoon | Acute intermittent porphyria | Guillain-Barré syndrome. Anxiety crisis. Non-therapeutic sedation. Anaphylaxis. Panic attack. |

A total of 131 secondary topics were identified. The number of secondary topics in each episode ranged from 1 (#13) to 16 (#10). In 32 episodes, secondary topics were considered pharmacological issues; in one episode (#7), five secondary topics were considered pharmacological issues.

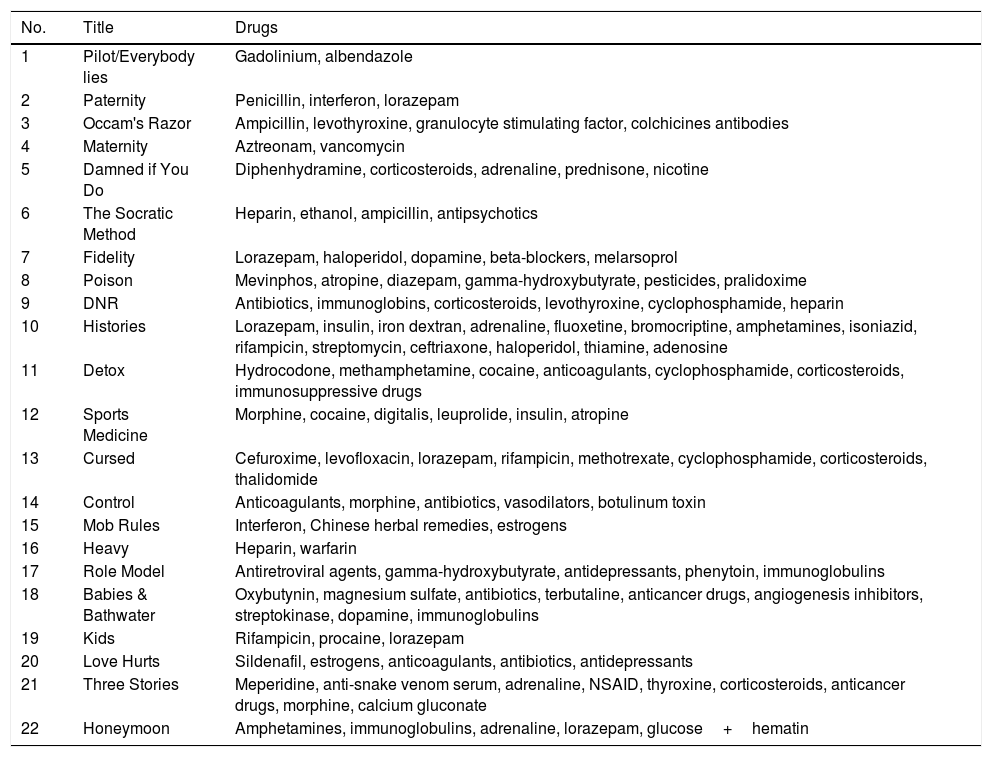

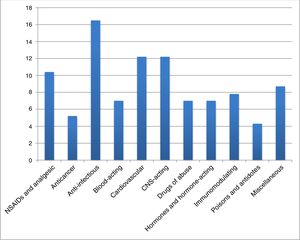

DrugsTable 3 shows the drugs that appeared in the episodes; 115 drugs appeared (mean, 5.2 drugs/episode). Fig. 1 shows the drugs by pharmacological group; the most common drug groups were anti-infectious drugs (n=19, 16.5%), cardiovascular drugs (n=14, 12.2%), central nervous system acting drugs (n=14, 12.2%), analgesic and anti-inflammatory drugs (n=12, 10.4%), and miscellaneous drugs (n=10, 8.7%). The drugs that appeared most often were anticoagulants and benzodiazepines (each appearing in 7 episodes), followed by corticosteroids and β-lactam antibiotics (each appearing in 6 episodes).

Drugs portrayed in the episodes of the first season of House, M.D.

| No. | Title | Drugs |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pilot/Everybody lies | Gadolinium, albendazole |

| 2 | Paternity | Penicillin, interferon, lorazepam |

| 3 | Occam's Razor | Ampicillin, levothyroxine, granulocyte stimulating factor, colchicines antibodies |

| 4 | Maternity | Aztreonam, vancomycin |

| 5 | Damned if You Do | Diphenhydramine, corticosteroids, adrenaline, prednisone, nicotine |

| 6 | The Socratic Method | Heparin, ethanol, ampicillin, antipsychotics |

| 7 | Fidelity | Lorazepam, haloperidol, dopamine, beta-blockers, melarsoprol |

| 8 | Poison | Mevinphos, atropine, diazepam, gamma-hydroxybutyrate, pesticides, pralidoxime |

| 9 | DNR | Antibiotics, immunoglobins, corticosteroids, levothyroxine, cyclophosphamide, heparin |

| 10 | Histories | Lorazepam, insulin, iron dextran, adrenaline, fluoxetine, bromocriptine, amphetamines, isoniazid, rifampicin, streptomycin, ceftriaxone, haloperidol, thiamine, adenosine |

| 11 | Detox | Hydrocodone, methamphetamine, cocaine, anticoagulants, cyclophosphamide, corticosteroids, immunosuppressive drugs |

| 12 | Sports Medicine | Morphine, cocaine, digitalis, leuprolide, insulin, atropine |

| 13 | Cursed | Cefuroxime, levofloxacin, lorazepam, rifampicin, methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, corticosteroids, thalidomide |

| 14 | Control | Anticoagulants, morphine, antibiotics, vasodilators, botulinum toxin |

| 15 | Mob Rules | Interferon, Chinese herbal remedies, estrogens |

| 16 | Heavy | Heparin, warfarin |

| 17 | Role Model | Antiretroviral agents, gamma-hydroxybutyrate, antidepressants, phenytoin, immunoglobulins |

| 18 | Babies & Bathwater | Oxybutynin, magnesium sulfate, antibiotics, terbutaline, anticancer drugs, angiogenesis inhibitors, streptokinase, dopamine, immunoglobulins |

| 19 | Kids | Rifampicin, procaine, lorazepam |

| 20 | Love Hurts | Sildenafil, estrogens, anticoagulants, antibiotics, antidepressants |

| 21 | Three Stories | Meperidine, anti-snake venom serum, adrenaline, NSAID, thyroxine, corticosteroids, anticancer drugs, morphine, calcium gluconate |

| 22 | Honeymoon | Amphetamines, immunoglobulins, adrenaline, lorazepam, glucose+hematin |

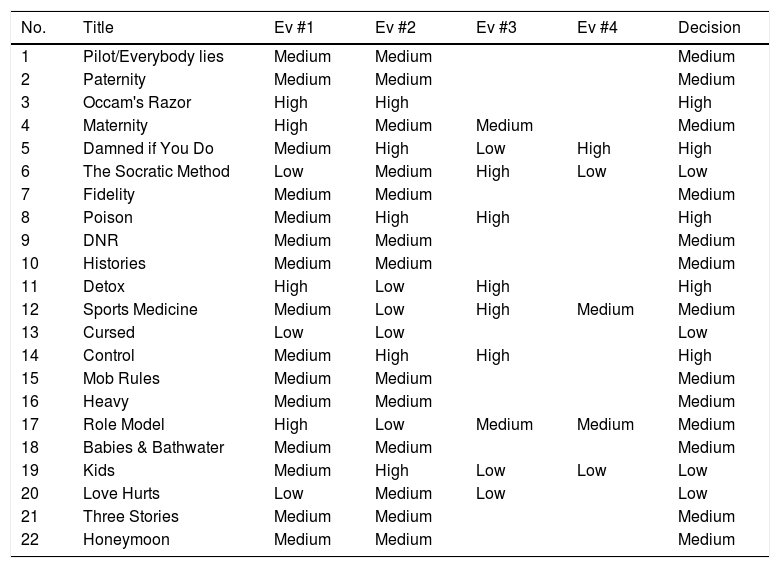

Table 4 reports the evaluators’ ratings for the interest of each episode. Interest was considered high in 5 episodes, medium in 13, and low in 4. The two initial evaluators’ rating were concordant for 12 (54.5%) episodes; the third evaluator's rating resolved the discrepancy for 5 (22.7%) episodes, and the fourth evaluator's rating resolved it in the remaining 5 (22.7%). Among the five episodes finally classified as high interest, the initial two evaluators’ ratings were concordant for only one episode; the third evaluator's rating was sufficient for three episodes, and the four evaluator's rating was required for one episode. By contrast, the two initial evaluators’ ratings were concordant in 10 of the 13 episodes finally classified as medium interest.

Scores of the evaluators (Ev) and their agreement in the interest of each chapter for teaching clinical pharmacology [categories: A: high interest; B: medium interest; C: low interest; see text for details].

| No. | Title | Ev #1 | Ev #2 | Ev #3 | Ev #4 | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pilot/Everybody lies | Medium | Medium | Medium | ||

| 2 | Paternity | Medium | Medium | Medium | ||

| 3 | Occam's Razor | High | High | High | ||

| 4 | Maternity | High | Medium | Medium | Medium | |

| 5 | Damned if You Do | Medium | High | Low | High | High |

| 6 | The Socratic Method | Low | Medium | High | Low | Low |

| 7 | Fidelity | Medium | Medium | Medium | ||

| 8 | Poison | Medium | High | High | High | |

| 9 | DNR | Medium | Medium | Medium | ||

| 10 | Histories | Medium | Medium | Medium | ||

| 11 | Detox | High | Low | High | High | |

| 12 | Sports Medicine | Medium | Low | High | Medium | Medium |

| 13 | Cursed | Low | Low | Low | ||

| 14 | Control | Medium | High | High | High | |

| 15 | Mob Rules | Medium | Medium | Medium | ||

| 16 | Heavy | Medium | Medium | Medium | ||

| 17 | Role Model | High | Low | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| 18 | Babies & Bathwater | Medium | Medium | Medium | ||

| 19 | Kids | Medium | High | Low | Low | Low |

| 20 | Love Hurts | Low | Medium | Low | Low | |

| 21 | Three Stories | Medium | Medium | Medium | ||

| 22 | Honeymoon | Medium | Medium | Medium |

The present study shows that the use of drugs and other pharmacological issues are widely represented in the medical drama House, M.D. Pharmacological topics are dealt with in most episodes and are the main topic in six. These findings confirm the potential interest of this television series as a pedagogical tool to complement the use of traditional teaching activities.

Hoffman et al.34 analyzed the use of television medical dramas in health sciences education in a systematic review, finding that ER and Grey's Anatomy were the most commonly used in reported studies; House was used in several studies to educate in ethics and professionalism15,16,34,37 and doctor/patient communication.19 The authors concluded that the use of television medical dramas in classroom settings helped students learn. However, none of the included studies were used specifically for teaching clinical pharmacology.

Only a few content analyses of medical dramas have been published. Makoul and Peer24 carried out the first study, analyzing how healthcare issues, doctors, and patients were portrayed and the primary frames highlighting medicine, doctors, and patients in ER and Chicago Hope. However, they did not consider any aspects related to drug therapy.

Another content analysis focused on the depiction of illness and other matters, including therapy, in Grey's Anatomy and ER.29 The authors reported that drug treatment was used in 40% of episodes. Although they carried out no further analyses of drug treatments in these series, their results suggested that drugs were very common in television medical dramas and that this aspect might be of interest in the teaching of pharmacology. Czarny et al.15 surveyed the contents of a season of Grey's Anatomy and House MD to analyze bioethics and professionalism. They concluded that both of them were rife with powerful portraits of bioethical issues and important deviations from the norms of professionalism. Both series have been used as pedagogical tools in recent years.34,38

Cowley et al.39 recently published the only pharmacological analysis of television medical dramas, in which they assessed the appropriateness of medications in five series, including House. House was considered the most useful of all the medical dramas analyzed, and this finding supports our choice of House for the current study. Their main conclusions were that drugs were often used for their correct indications, but that other aspects, such as key safety checks or medication-related advice, were frequently omitted; our analysis did not consider safety checks or advice related to medication. Although the mean number of drugs used in each episode of House in our study (5.2) was similar to the mean reported in their analysis (6), there were some minor differences in the drug categories. Whereas they found that cardiovascular drugs were the most common, followed by anti-infective drugs, we found that anti-infective drugs were the most common, followed by cardiovascular drugs. These authors did not specify the seasons that they reviewed in their analysis, and this might explain some discordance between their results and ours. However, we consider that the two studies generally agree on most figures related to drug use.

One important issue that teachers take into account when considering whether to use particular medical dramas is the accuracy and plausibility of the facts depicted in the episodes. In the end, it boils down to whether the fictional portrayal reflects plausible medical circumstances. We did not analyze the full accuracy of all medical topics in the first season of House but only the pharmacological ones. However, certain circumstances suggest that the treatment given to medical topics might be accurate. The technical consultant of the series, Dr. Lisa Sanders, an associate lecturer at Yale University School of Medicine and a columnist for the New York Times Magazine, recently explained the origins of House and how the medical content of each episode was considered.40 She reviewed each chapter to identify inaccuracies in the script and confirmed that they were righted in the final versions of the episodes, although some infrequent situations were accepted to make them more attractive to the public. In an example of the veracity and usefulness of the medical information in the series, Dahms et al.41 reported that an episode of House helped them reach the diagnosis of cobalt intoxication in one of their patients.

We also reviewed the scientific evidence for the content of two episodes that we considered potentially useful for teaching clinical pharmacology. For the first, Poison (episode #8), we found an article that justified the assumptions in the episode, where a patient was poisoned by wearing clothing impregnated with an organophosphate.42 For the second, Control (#14), the possibility of developing cardiomyopathy by ipecac ingestion is clearly established in the literature.43 Therefore, we believe that the medical information presented in most episodes of House is probably accurate, although teachers should review all episodes carefully before using them to teach medical students.

Interestingly, the two initial evaluators’ ratings were concordant for 12 (54.5%) of the episodes; a third evaluator was needed for 10 episodes, and a fourth evaluator was needed for only 5 episodes. We did not address the reasons for these discrepancies; we speculate that the evaluators’ different academic backgrounds and experiences might help explain them. In any case, two evaluators were sufficient to qualify more than half of the episodes and two or three were sufficient to qualify more than three quarters of them, suggesting acceptable agreement among evaluators in this study.

An important point regarding the use of House, M.D. for teaching medical students is concern about his behavior when treating patients. As Sanders40 pointed out, his inappropriate approach to the doctor–patient relationship was chosen to set this medical drama apart from previous ones, where the physicians were kind and respectful with their patients.28 For some authors, House also reflects the outmoded paradigm of medical paternalism, a situation that is not uncommon in the real world.32 However, the situation depicted in the series is so exaggerated that it is difficult to believe that students would consider this way of behaving acceptable under any circumstances. In fact, House, M.D. can be used to highlight important ethical issues, as it portrays the way a physician never should behave.33 A recent study has also shown how it may successfully be used to motivate medical students in the learning of rare diseases.44

A recent survey in United Kingdom showed that 65% of doctors stated they had watched medical dramas on more than one occasion.45 Even though most watched them for entertainment, 8% also watched them for educational purposes; of these, all watched House, M.D. Most considered that medical series did not accurately portray real practice, and only 10% thought they did. Junior doctors were more likely to identify with some aspects of clinical practice depicted in the episodes. Hirt et al.12 suggested how House, M.D. should be used in medical education, and outlined the interest of using some clips from episodes of this series in the clinic, as well as their usefulness for beginning learners. We agree that clips are useful, but we stress that they should be carefully chosen; we prefer to use the full episode to benefit from the storyline. The main drawback of using full episodes is the need to assign time for this activity instead of including the episode in regular teaching activities, such as lectures.

A thorough content analysis of the episodes was the first step to obtain evidence on the presence of pharmacological issues in the episodes before tackling the question of to what extent this medical drama would be to useful for teaching clinical pharmacology to medical students. We are designing an experimental study to address this question and to establish if they can improve the learning and understanding of pharmacological issues of medical students.

In conclusion, we found that drug treatments and pharmacological issues are highly prevalent in House, MD. A preliminary analysis also showed that the use of drugs is accurate and that some of the episodes might be useful for teaching clinical pharmacology to medical students. Their use as educational adjuvant, but not as a substitute of regular learning, merits further assessment. The present study only analyzed how drug treatments appeared in this medical drama but not established the actual value in teaching the discipline. An empirical study is needed to confirm this possibility and to further recommend television medical dramas in medical education.

Conflict of InterestThe authors of this article declare no conflict of interest.

Group members: Ana Lucía Arellanoc,d, Ana Maria Barriocanalc,d, Inmaculada Bellidob, Encarnación Blancob, María del Rosario Cabellob, Anna Lópezc,d, Eva Montanéc,d, Esther Papaseitc,d, Clara Pérez-Mañác,d, Jordi Planesa, Judith Sanabriab, Mahmoud Slimb, Sebastià Videlaa and Judith Villara.

A preliminary version of this study was presented in the XXXVI Congress of the Spanish Society of Pharmacology, held in Valencia in 2015.