Although previous research has indicated that emotional abilities substantially affect teacher work-related well-being and motivation, studies examining the potential paths in which emotional intelligence relates to job satisfaction and intention to quit are limited. The current study examined a serial mediation model including a personal resource, i.e., emotional intelligence, as a predictor of job resources (i.e., perceived support from colleagues and supervisors), job satisfaction, and intention to quit. A total of 1,079 teaching professionals (651 female; Mage = 44.07 years) took part in this study. The teaching levels include: preschool, primary and secondary schools. A serial mediation model was tested with the SPSS macro PROCESS (model 80). Results supported a model showing that higher emotional intelligence was associated with lower teachers’ intention to quit via two indirect pathways: (a) higher job satisfaction and (b) higher perceived support from supervisors followed by higher job satisfaction. This study adds to our understanding of how personal and contextual resources may allow teachers to feel satisfied at work and less likely to consider withdrawal from work.

Aunque investigaciones previas han indicado que las habilidades emocionales afectan sustancialmente al bienestar ocupacional y la motivación del profesorado, los estudios que examinan las posibles vías por las cuales la inteligencia emocional se relaciona con la satisfacción laboral y con la intención de abandono son escasos. El presente estudio ha examinado un modelo de mediación serial incluyendo un recurso personal, i.e., inteligencia emocional, como un predictor de los recursos laborales (i.e., apoyo percibido de colegas y supervisores), satisfacción laboral e intención de abandono. Un total de 1.079 profesionales de la enseñanza (651 mujeres; Medad = 44.07 años) ha participado en este estudio. Los niveles de enseñanza del profesorado incluyen: preescolar, primaria y secundaria. Se ha analizado un modelo de mediación serial mediante la macro PROCESS de SPSS (modelo 80). Los resultados han apoyado un modelo que muestra que mayores niveles de inteligencia emocional se asocian con una menor intención de abandono docente a través de dos vías indirectas: (a) una mayor satisfacción laboral y (b) un mayor apoyo percibido de supervisores seguido de una mayor satisfacción laboral. Este estudio contribuye a la comprensión de cómo los recursos personales y contextuales pueden permitir que el profesorado se sienta satisfecho en el trabajo y menos propenso a considerar el abandono.

Teachers face a complex and dynamic reality with a variety of demanding situations that have an impact on occupational well-being and job attitudes toward teaching (Chang, 2009; Iriarte-Redín & Erro-Garcés, 2020). For instance, recent data from the Eurydice Report highlighted several stressful working conditions (e.g., students’ discipline management and lack of administrative support), leading to concerning levels of work stress (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2021). Such job-related aspects make teachers experience negative work attitudes, including low satisfaction and intention to quit (Iriarte-Redín & Erro-Garcés, 2020; Torenbeek & Peters, 2017).

A number of studies have examined potential factors that predict teachers’ cognitions and feelings that increase teacher attrition, as intention to quit is a key predictor of eventual withdrawal behaviours (Wang & Hall, 2021). On the one hand, intention to quit and eventual teacher attrition remain a heavy burden for educational systems and public administrations given the economic costs associated with presenteeism, substitutions, and teacher abandonment (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2021; Torenbeek & Peters, 2017; Wang & Hall, 2021). On the other hand, teachers experiencing a desire to quit teaching show a reduced capacity to deal with conflicting situations or to provide adequate support for students’ needs (Chang, 2009; Torenbeek & Peters, 2017). Indeed, teachers’ negative work attitudes impair students’ learning, well-being, and the achievement of academic goals (Madigan & Kim, 2021; UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2016). Considering the Horizon 2030 and existing educational goals for the next decade, the need for scientific efforts directed at facilitating teachers’ positive work attitudes and retention remains a major challenge (UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2016).

Existing research following the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) theory has primarily explored the contextual variables (e.g., workplace social support) leading teachers to show decreased intentions to quit their job (Granziera et al., 2021). There are also several sociodemographic variables (e.g., gender, age, and teaching experience) that have shown significant effect in teachers’ decisions about leaving their occupation (Borman & Dowling, 2008). Beyond these contextual factors, there are individual dimensions (e.g., emotional intelligence) accounting for differences in teachers’ intentions to quit (Bardach et al., 2021). Available evidence supports that both emotional intelligence and workplace social support would positively associate with teachers’ job satisfaction and their intention to quit (e.g., Mérida-López, Sánchez-Gómez et al., 2020). Therefore, this study examines the relations among these variables seeking to develop a deeper understanding on the association between teachers’ personal and social resources and their intention to quit. Such an approach would contribute to the development of effective preventive intervention programs focusing on the enhancement of personal resources for facilitating teachers’ positive work functioning and retention.

Emotional intelligence as a predictor of teachers’ intention to quitIn line with the JD-R theory (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017), personal resources such as emotional intelligence are found to explain between-person differences regarding their levels of work-related well-being and, eventually, the extent to which some teaching professionals may decide to leave their career (Granziera et al., 2021; Mérida-López, Sánchez-Gómez et al., 2020). Teaching work involves high levels of emotional demands as well as affectively charged interactions, where numerous interpersonal events with students, families, and colleagues take place (Chang, 2009). In fact, teachers’ skills regarding emotional management emerge as strong predictors of their cognitions, feelings, and behaviours regarding their work (Iriarte-Redín & Erro-Garcés, 2020; Wang & Hall, 2021). Thus, emotional intelligence (EI), a theoretical construct encompassing the ability to perceive, understand, and manage one’s own and others’ emotions, has attracted extensive attention in the teaching context (Bardach et al., 2021; Vesely et al., 2013).

Following the ability model, EI is defined as the ability to perceive emotions and to express emotions and emotional needs accurately to others, understand emotions and emotional knowledge, and the ability to regulate emotions to promote emotional and intellectual growth (Mayer & Salovey, 1997). These emotional abilities have been underscored as a key personal resource with implications for relevant processes underlying teacher retention (Bardach et al., 2021; Granziera et al., 2021). For example, following the affective events theory (AET) at work, EI may allow teachers to display a wider capacity to deal with challenging situations which, in turn, may have an impact on distal work-related attitudes including lower intentions to abandon their career (Ashkanasy & Dorris, 2017; Bardach et al., 2021). The robust negative relationship between EI and intention to quit has been reported in a meta-analytic review, finding that emotionally intelligent professionals scored lower in intention to quit their job than did their counterparts with fewer emotional skills (Miao et al., 2017a). In teacher samples, similar results have been reported, indicating that teaching professionals scoring higher in EI show greater commitment and lower intention to abandon their career (Anari, 2012; Mérida-López, Sánchez-Gómez et al., 2020).

Job satisfaction as a mediator in the EI–intention to quit relationshipDespite the empirical links between higher EI and teachers’ lower intention to quit, there is limited research testing the mechanisms underlying this relationship (Bardach et al., 2021). One of the potential pathways through which EI may associate with reduced intention to quit is job satisfaction. Job satisfaction is defined as an evaluative state involving contentment with and positive feelings resulting from the appraisal of one’s job (Judge et al., 2009). Meta-analytic evidence has supported the causal effects of job satisfaction on reduced intention to quit (Judge et al., 2009).

Among the potential antecedents of job satisfaction, EI exerts a positive influence on individuals’ perceptions and feelings regarding their jobs, thereby showing positive associations with both general and teacher-related satisfaction (Miao et al., 2017a; Yin et al., 2019). Following the JD-R theory as well as the AET at work, teachers with higher emotional skills would feel more capable of controlling work environment characteristics. This would make them more likely to feel greater satisfaction and positive feelings with their work (Ashkanasy & Dorris, 2017; Granziera et al., 2021). In sum, it is reasonable to expect that emotionally skilled teachers perceiving more positive job-related emotions and feeling more satisfied with their teaching tasks would report lower intention to quit than their counterparts who perceive themselves with fewer emotional skills.

Perceived social support as a mediator in the EI–job satisfaction relationshipAlthough there is a growing literature showing that teachers’ EI may help teachers to experience greater satisfaction with their jobs and lower desires to quit their teaching career, there is a need for studies testing the underlying factors relating EI with intention to quit (Bardach et al., 2021). From the JD-R theory, job resources are psychosocial factors reducing the costs associated with job demands and, thus, stimulating growth and achievement of work goals (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017). A wide range of contextual factors are expected to influence the degree to which teachers may feel satisfied with and committed to their job (Granziera et al., 2021). In particular, perceiving support at work is a key job resource associated with work-related motivation and retention (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017; Granziera et al., 2021). In this study, we focus on two distinct yet related types of organizational support reflecting perceived support from colleagues and supervisors. Perceptions of organizational support regarding colleagues and feedback on classroom management from supervisors are typically associated with higher teacher satisfaction and positive attitudes towards the teaching profession (Granziera et al., 2021; Mérida-López, Sánchez-Gómez et al., 2020).

With regard to the sources of teachers’ organizational support, the JD-R theory places personal resources (i.e., EI) as antecedents of these job resources (Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). It has been demonstrated that emotionally intelligent workers maintain more significant and positive relationships at work and, hence, they perceive their work environment as more supportive and collaborative than do their counterparts with lower EI skills. This would lead them to feel more content and satisfied with their work (Miao et al., 2017b). Although organizational support has been proposed as a mediator in the relationship between EI and teacher burnout, the role of perceived organizational support as a mediator explaining the relationships among EI, job satisfaction, and intention to quit remains unclear (Ju et al., 2015). Considering this gap, a critical problem requiring attention is to explore the possible effects of EI on intention to quit via indirect effects involving workplace social support and positive work attitudes. Based upon previous research and theory, EI would impinge on teachers’ perceptions of their organization as more supportive, which, in turn, would lead to increased job satisfaction and to decreased intention to quit.

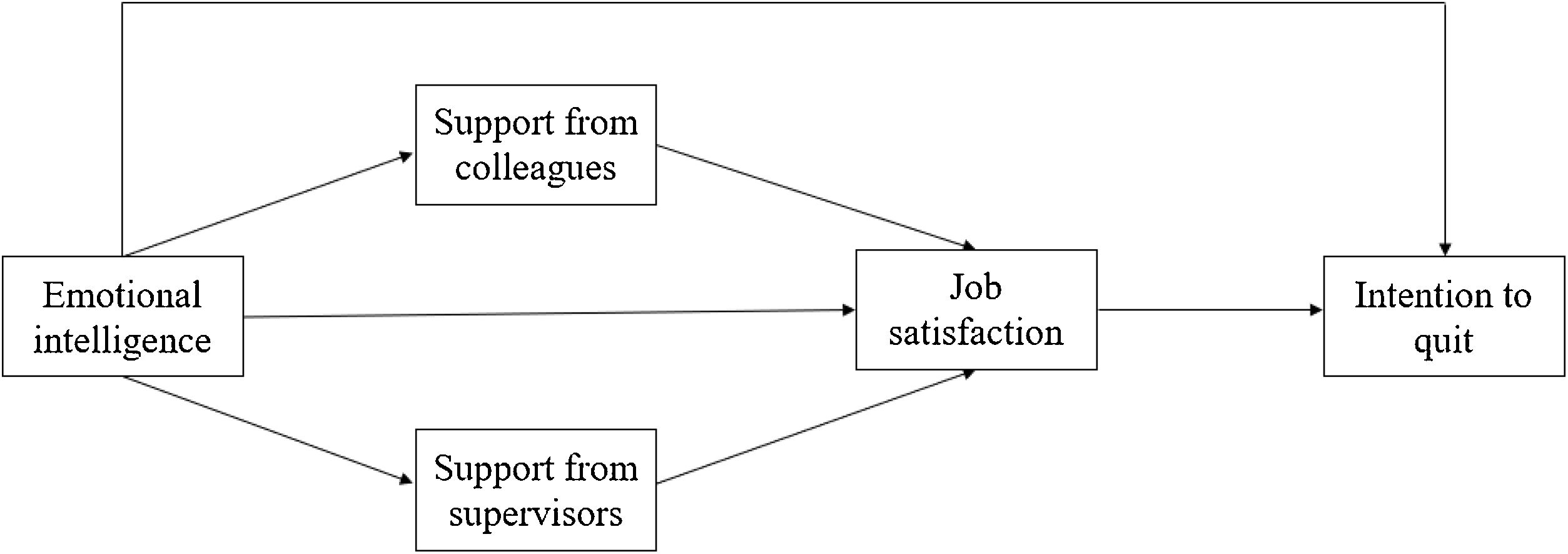

The present studyThere is a strong theoretical background supporting the fact that teachers’ EI may act as a predictor of increased job resources (Miao et al., 2017b; Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). However, the role of job resources as mediators in the relationship between EI and job satisfaction and associated intention to quit has been scarcely explored. Such an examination would be relevant for designing future training programs aimed at developing emotional skills and social relationships that may enhance teachers’ positive feelings and perceptions regarding their work so that eventual retention could be facilitated. Based upon the aforementioned background on EI and job resources and attitudes (Ashkanasy & Dorris, 2017; Miao et al., 2017b), the main goal of this study was to test a serial mediation model including EI, support from colleagues and supervisors, job satisfaction, and intention to quit (Figure 1). Based on previous findings presented above, the following hypotheses were set: (a) Job satisfaction is expected to mediate the relationship between EI and intention to quit (H1); and (b) EI is positively related to job satisfaction via perceived support from colleagues and support from supervisors, and, in turn, job satisfaction is negatively associated with intention to quit (H2).

MethodParticipantsApproximately 2,000 surveys were distributed among educational centres in southern Spain. Around 1,150 questionnaires were collected, thereby yielding a response rate of 57.5%. A total of 71 surveys were removed from analysis as they were fully incomplete. Thus, the total number of teaching professionals in this study was 1,079 (651 females), with a mean age of 44.07 years (SD = 8.93) and a mean teaching experience of 16 years. There were teachers from different levels as follows: secondary school teachers 57.8%; primary school teachers 29.7%; preschool teachers 10.9%; and 1.5% persons who did not specify the level of teaching. In this study, 503 participants (46.6%) were married, and 299 (27.7%) were single.

MeasuresEmotional intelligence was measured using the Spanish version of the Wong and Law Emotional Intelligence Scale (Extremera et al., 2019; Wong & Law, 2002). Participants self-reported across 16 items using a 7-point response scale ranging from 1 = totally disagree to 7 = totally agree. The Spanish version of the scale has shown adequate psychometric properties in previous studies with teaching professionals (e.g., Mérida-López, Extremera et al., 2020). In this study, reliability was excellent (α = .92, Ω = .92, CR = .90, AVE = .69).

Social support from colleagues and supervisor was assessed using the Spanish version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire II (Moncada et al., 2014; Pejtersen et al., 2010). This scale is composed of two brief subscales regarding perceived support from colleagues and supervisors, with three items each. Both subscales were answered using 5-point response options from 1 = always to 5 = never. Scores were recoded and then summed and divided by the number of items so that higher scores reflected higher perceived support at work. The Spanish version of the scale has shown good reliability in prior research with teachers (e.g., Mérida-López, Sánchez-Gómez et al., 2020). In this work, the scale showed satisfactory reliability for both support from colleagues (α = .79, Ω = .80, CR = .80, AVE = .58) and for support from supervisors (α = .82, Ω = .84, CR = .84, AVE = .64).

Job satisfaction was assessed using the Spanish version of the Job Satisfaction Scale (Extremera et al., 2018; Judge et al., 1998), which is a brief measure of overall job satisfaction including five items rated on 7-point response options from 1 = completely disagree to 7 = completely agree. The Spanish adaptation of the scale has shown adequate psychometric properties in multi-occupational samples including teachers (Extremera et al., 2018). In this study, reliability was satisfactory (α = .80, Ω = .80, CR = .82, AVE = .49).

Intention to quit was measured using the Occupational Withdrawal Intentions Scale (Hackett et al., 2001; Klassen & Chiu, 2011) that comprises three items with 9-point response options ranging from 1 = disagree strongly to 9 = agree strongly. The original version was translated from English into Spanish using the back-translation method (Beaton et al., 2000). This scale has shown adequate internal consistency with Spanish teacher samples (Mérida-López, Sánchez-Gómez et al., 2020). In this study, reliability was excellent (α = .93, Ω = .92, CR = .92, AVE = .79).

The survey also included sociodemographic information (i.e., gender, age, teaching level, and teaching experience). These sociodemographic factors were used as covariates because they have been constantly related to teachers’ job attitudes and retention indicators (Borman & Dowling, 2008).

ProcedureA non-probability and convenience sampling technique was adopted following the guidelines and recommendations for student-recruited sampling (Wheeler et al., 2014). Potential participants were contacted by psychology students who had been previously trained in the administration of questionnaires by the research staff. Several educational centres located in Southern Spain were contacted, asking teachers to participate in a voluntary, individual, and anonymous survey on psychosocial factors and work attitudes in the teaching context. For instance, potential participants were given an introduction to the main goal of the study, and the voluntary and confidential nature of their participation was underlined. Completing the surveys lasted around 20 minutes. There was a period of six weeks between contacting the educational centres and collecting the last completed surveys. Once the filled in surveys were collected, they were returned to the research staff for further statistical processing in sealed envelopes to ensure anonymity. The research protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Málaga (66/2018-H).

Data analysisAfter descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations were investigated to examine associations among variables, a serial mediation (model 80) was tested with SPSS 24.0 software and macro PROCESS v3.5 (Hayes, 2018). This computational technique generates highly accurate confidence intervals through bootstrapping, thereby accounting for the possibility of non-normality in the sampling distribution and providing similar results to those generated in structural equation models (Hayes et al., 2017). Following standard procedures, analyses included 5,000 bootstrapping samples and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). An indirect effect, indicating the effect of VI on DV through the mediators, was considered significant if the 95% bootstrapped confidence interval excluded zero (Hayes, 2018). Preliminary analyses were conducted prior to main analyses, and multicollinearity tests showed correlations lower than 0.84 and VIF values ranged between 1.07 and 1.74. Moreover, to avoid possible effects of heteroskedasticity on the validity of inferences, HC3, a heteroskedasticity-consistent estimator, was employed (Hayes, 2018). Sociodemographic factors (i.e., gender, age, teaching level, and experience) were used as covariates to control for their potential effects on our results.

ResultsDescriptive analysisBivariate correlations among study measures were computed before performing the mediational analyses (Table 1). As can be observed, EI was positively related to perceived support from colleagues and supervisors as well as to job satisfaction. Perceived support from colleagues and supervisors was positively related to job satisfaction. Moreover, intention to quit was negatively associated with all of the key variables.

Descriptive statistics of the sample and correlations between study variables

| M (SD) | Range | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Emotional intelligence | 5.55 (0.73) | 1.94-7 | – | |||

| 2. Perceived support from colleagues | 3.60 (0.87) | 1-5 | 0.17 | – | ||

| 3. Perceived support from supervisors | 3.59 (1.01) | 1-5 | 0.19 | 0.64 | – | |

| 4. Job satisfaction | 5.60 (1.02) | 1-7 | 0.38 | 0.22 | 0.23 | – |

| 5. Intention to quit | 1.81 (1.61) | 1-9 | -0.17 | -0.15 | -0.14 | -0.42 |

Note. All values were significant at p < .001 level.

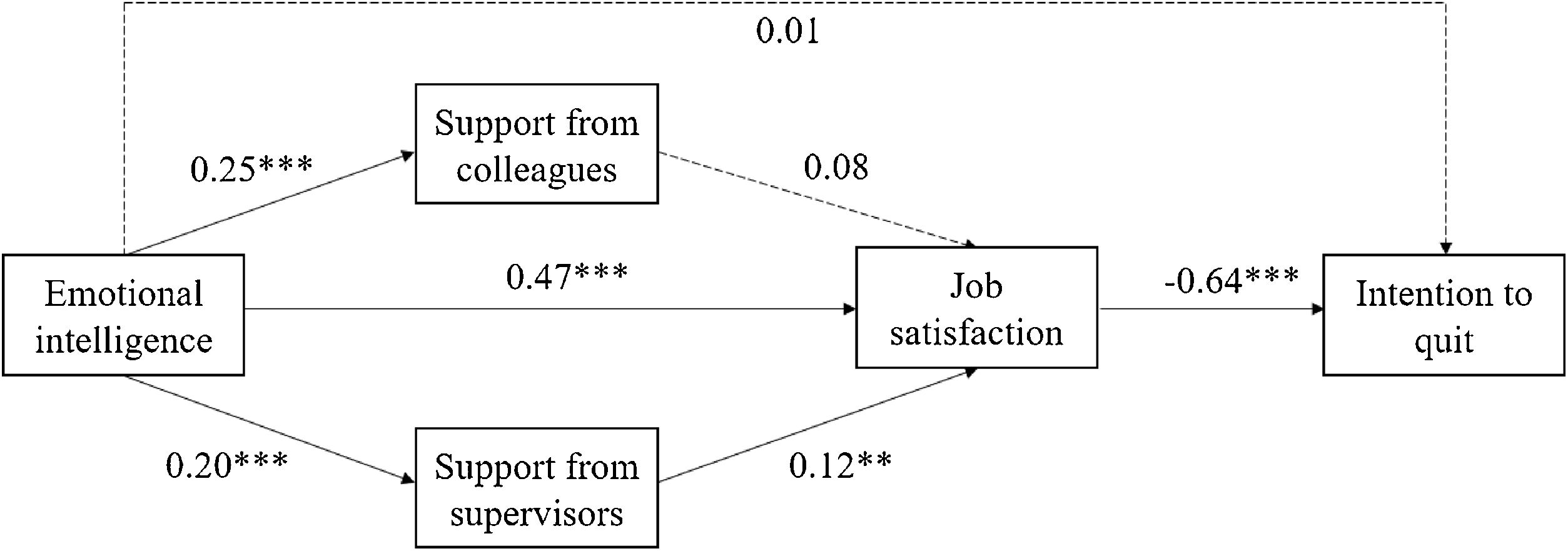

To test the theoretical model predicting direct and indirect effects on the relationship between EI and intention to quit (Figure 1), we used PROCESS macro 3.0 (Model 80; Hayes, 2018). Intention to quit was the outcome variable, and perceived support (from colleagues and supervisors) together with job satisfaction were the sequential mediators. The results are summarized in Table 2.

Direct and indirect effects of EI on job satisfaction and intention to quit

| Predictors | Estimated effect | SE (HC3) | R2 | t | 95 % Bias-Corrected CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome: Support from colleagues | 0.04*** | ||||

| Gender | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.80 | -0.07 to 0.15 | |

| Age | -0.01 | 0.01 | -1.51 | -0.02 to 0.00 | |

| Teaching experience | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.43 | -0.00 to 0.00 | |

| Teaching level | -0.06 | 0.04 | -1.52 | -0.13 to 0.02 | |

| Emotional intelligence (EI) | 0.20*** | 0.04 | 4.96 | 0.12 to 0.27 | |

| Outcome: Support from supervisors | 0.04*** | ||||

| Gender | -0.10 | 0.06 | -1.53 | -0.22 to 0.03 | |

| Age | -0.02** | 0.01 | -2.63 | -0.03 to -0.00 | |

| Teaching experience | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.86 | 0.00 to 0.00 | |

| Teaching level | -0.01 | 0.04 | -0.30 | -0.10 to 0.07 | |

| EI | 0.25*** | 0.04 | 5.85 | 0.17 to 0.34 | |

| Outcome: Job satisfaction | 0.20*** | ||||

| Gender | 0.16** | 0.06 | 2.61 | 0.04 to 0.28 | |

| Age | -0.01 | 0.01 | -1.51 | -0.02 to 0.00 | |

| Teaching experience | 0.00 | 0.00 | -0.23 | -0.00 to 0.00 | |

| Teaching level | -0.10** | 0.04 | -2.93 | -0.17 to -0.03 | |

| EI | 0.47*** | 0.05 | 9.39 | 0.37 to 0.57 | |

| Support from colleagues | 0.08 | 0.05 | 1.80 | -0.01 to 0.18 | |

| Support from supervisors | 0.12** | 0.04 | 2.93 | 0.04 to 0.20 | |

| Outcome: Intention to quit | 0.18*** | ||||

| Gender | -0.05 | 0.10 | -0.51 | -0.24 to 0.14 | |

| Age | -0.00 | 0.01 | -0.07 | -0.02 to 0.02 | |

| Teaching experience | 0.00 | 0.00 | -0.24 | -0.00 to 0.00 | |

| Teaching level | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.71 | -0.07 to 0.16 | |

| EI | -0.01 | 0.07 | -0.13 | -0.15 to 0.14 | |

| Support from colleagues | -0.08 | 0.07 | -1.19 | -0.22 to 0.06 | |

| Support from supervisors | -0.02 | 0.05 | -0.41 | -0.13 to 0.08 | |

| Job satisfaction | -0.64*** | 0.06 | -10.39 | -0.76 to -0.52 | |

| Indirect effects | |||||

| Total indirect effect | -0.35 | 0.05 | -0.45 to -0.26 | ||

| EI → job satisfaction → intention to quit | -0.30 | 0.05 | -0.39 to -0.22 | ||

| EI → support from supervisors → job satisfaction → intention to quit | -0.02 | 0.01 | -0.04 to -0.01 | ||

| Total effect | -0.36*** | 0.08 | 0.04*** | -4.57 | -0.52 to -0.21 |

Note. Unstandardized coefficients; SE = Standard error of beta coefficients; HC3 = heteroscedasticity consistent standard error; CI = Confidence Intervals.

As predicted, EI was positively related to job satisfaction, which was negatively related to intention to quit, resulting in a significant and negative indirect effect via job satisfaction (effect = 0.30, SE = 0.05; 95% CI [-0.39 to -0.22]). The completely standardized indirect effect was also significant (effect = -0.14; SE = 0.02; 95% CI [-0.18 to -0.10]). Thus, results showed that job satisfaction mediated the relationship between EI and intention to quit, thereby supporting H1.

Regarding H2, the total indirect effect between EI and intention to quit was significant (effect = -0.35, SE = 0.05; 95% CI [-0.45 to -0.26]), whereas the total direct effect was nonsignificant (effect = -0.10, SE = 0.07; 95% CI [-0.115 to 0.13]). Specifically, analyses revealed a negative indirect effect of EI on intention to quit through support from supervisors and job satisfaction (effect = -0.019, SE = 0.008; 95% CI [-0.035 to -0.006]). Likewise, the completely standardized indirect effect was significant (effect = -0.009; SE = 0.003; 95% CI [-0.016 to -0.003]). The indirect effect through support from colleagues was not found (effect = -0.011, SE = 0.007; 95% CI = [-0.025 to 0.001]). Regarding the covariates, age and teaching level showed negative associations with perceived support from supervisors and job satisfaction, respectively. In sum, H2 was partially supported. These results indicated that EI was positively related to job satisfaction only via support from supervisors, which, in turn, was negatively related to intentions to quit. The final serial model is depicted in Figure 2.

A limitation of the causal sequence of EI in intention to quit through support from colleagues and supervisors and job satisfaction is that all variables of interest have been simultaneously measured. We incorporated multiple mediating factors using Mode 81 in a reverse sequence (i.e., EI → job satisfaction → support from colleagues/supervisors → intention to quit) in order to test for robustness of the first theoretical model. Interestingly, findings from mediation analysis indicated that both types of support did not significantly predict intention to quit (colleagues estimated effect = –0.08, SE = 0.07; 95% CI [-0.22 to 0.06]; supervisors estimated effect = –0.02, SE = 0.05; 95% CI [-0.13 to 0.08]) and that EI showed a nonsignificant effect on intention to quit (estimated effect = –0.01, SE = 0.07; 95% CI [-0.15 to 0.14]). Further, the only significant indirect effect between EI and intention to quit was through job satisfaction (estimated effect = -0.33; SE = 0.05; 95% CI [-0.43 to -0.24]), that is, the same indirect effect observed in Model 80 to test H1.

DiscussionPrior research has underscored the predictive role of EI on work-related attitudes (Miao et al., 2017a). However, research on the potential mechanisms linking EI with relevant work attitudes among teachers is still scarce. Therefore, this study sought to determine whether EI may be associated with perceived social support and, in turn, with job satisfaction and, lastly, with intention to quit in a relatively large sample of in-service teachers.

First, correlation results showed EI to be positively related to both types of perceived social support and to job satisfaction, in line with previous studies (Ju et al., 2015; Miao et al., 2017b). Moreover, findings are consistent with past findings (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2011), confirming that perceived social support and job satisfaction are negatively linked with intention to quit. Finally, our results also indicate that EI was negatively linked with intention to quit (Miao et al., 2017a).

Second, the main results supported H1, indicating that EI was negatively associated with intention to quit through increased job satisfaction, which accords with existing theory on AET at work and is consistent with previous findings showing work-related well-being (e.g., work engagement) to mediate the association between teachers’ EI and withdrawal intentions (Ashkanasy & Dorris, 2017; Mérida-López, Extremera et al., 2020). Despite the clear recognition that personal resources such as EI may be critical for preserving work-related well-being in demanding occupations such as teaching, there is a strong need for efforts aimed at understanding how teachers’ emotional abilities may increase teacher retention (Bardach et al., 2021). Thus, this study provides new insights regarding the effects of personal resources such as EI on distal work-related outcomes including intention to quit a teaching career.

Third, H2 was partially supported by results showing that support from supervisors (but not from colleagues) mediated the relationship between EI and intention to quit through job satisfaction. In line with prior research, this finding suggests that perceptions of supervisor support become a stronger predictor of job satisfaction than support from colleagues in the teaching context (Sass et al., 2011). Considering teacher practices, it is possible that the influence of perceived support from supervisors on job satisfaction may occur through increased job resources such as support for autonomy and for classroom instruction issues, thereby placing colleague support at a less relevant position for predicting job satisfaction (Sass et al., 2011). Previous research findings have suggested that emotionally intelligent teachers would be more likely to engage in constructive social interactions with their principals (Miao et al., 2017b). Such relationships may lead to the perception of their work as more pleasant and fulfilling (Granziera et al., 2021).

Limitations and future lines of researchThere are several limitations of the study to be acknowledged. First, study variables were all assessed at the same time and so these results should be replicated in future investigations using diary studies to test both between-person and within-person relationships simultaneously (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017). Moreover, the study sample was primarily comprised of experienced in-service teachers with a relatively stable contractual status. Thus, future work is needed to compare the proposed model among samples of veteran and beginning teachers (Klassen & Chiu, 2011). This line would allow to gain a deeper insight into the potential differences in organizational support and in job attitudes by age and teaching level. Relatedly, the generalizability of the findings should be tested considering other teaching levels (e.g., university teachers; Galindo-Domínguez et al., 2020). Second, future work may consider measurement of EI and job resources with other approaches (e.g., performance measures, interviews, or peer reports). Further, it would be relevant to measure teacher work-related well-being with more objective indicators including sickness absence or actual turnover across time and using other random and nonpurposive sampling techniques.

Third, a general measure of perceived social support was used. Therefore, future studies are encouraged to use profession-specific instruments providing evidence on the motivational role of teachers’ emotional, informative, and instrumental support at work. These studies may also explore the potential boosting effect of social support in the prospective relationship between EI and work-related indicators. This line may advance limited knowledge regarding the role of EI within JD-R theory. Fourth, findings regarding the amount of variance explained in intention to quit underscore the need for exploring those factors unaccounted for in the link between EI and intention to quit. Therefore, future studies should test more integrative models (using structural equation approaches) with sociodemographic, contextual, and personal factors predicting key work-related antecedents of teachers’ intention to quit such as teacher engagement and burnout (Granziera et al., 2021). Finally, current results may serve for developing further works testing the validity of specific EI facets in serial prospective models for explaining teachers’ intention to quit.

Theoretical and practical implications of this researchLimitations notwithstanding, this work presents some strengths such as underscoring the need for expanding theoretical frameworks sustaining teacher professional development. Moreover, this study adds to our understanding of how personal and contextual resources may allow experienced teachers to feel satisfied at work and less likely to consider withdrawal, which contributes to limited literature in this field (Torenbeek & Peters, 2017). This study is among the first attempts to examine the potential job-related mechanisms linking teachers’ EI with work attitudes including job satisfaction and intention to quit in a sample of experienced teachers that are at certain risk of attrition and reduced performance (Torenbeek & Peters, 2017).

Results suggested that the effect of EI on enhanced job satisfaction may occur not only directly but also indirectly through positive social relationships (Miao et al., 2017b). More interestingly, findings underscored EI as a key personal resource for increasing teacher satisfaction and associated desire to remain in a teaching career (Bardach et al., 2021). These results are in line with the notion that emotionally intelligent teachers may perceive themselves as more resourceful at work, which may promote active processes leading to increased perceptions of their principals as supportive; in turn, this may strengthen their judgments about their work as satisfying and pleasant (Ashkanasy & Dorris, 2017). Further, our results are in line with Miao and colleagues' (2017b) meta-analytic review corroborating that teachers’ emotional resources primarily influence the development of positive work attitudes because they reinforce their job resources, rather than vice versa.

Current findings providing evidence on the mechanisms linking EI with teachers’ intention to quit may be helpful for designing effective programs targeting satisfaction and positive teacher job attitudes. Teacher attrition remains a global concern given its economic, social, and educational effects (Torenbeek & Peters, 2017). Further, teachers perceiving their profession as satisfying and committed to their career would impact positively on student learning and would also facilitate the implementation of EI training programs in schools (Bardach et al., 2021; Viguer et al., 2017). Therefore, these results may encourage future efforts providing guidance to school administrators and policymakers to reduce dissatisfaction and intention to quit among teachers.

On the one hand, results might suggest that incorporating EI training into programs for professional development may increase teachers’ strategies to adaptively cope with daily stressful teaching experiences and events (Vesely et al., 2013). Such an approach may increase teachers’ positive judgments about their work, which, in turn, may reduce their intention to abandon their career (Wang & Hall, 2021). On the other hand, providing teachers with opportunities to increase their knowledge on how emotions affect their work lives and their work-related attitudes may result in a higher sensitivity to perceive their work environment as constructive and supportive. Thus, teachers may acquire strategies to build collaborative relationships with their principals to strengthen their perceptions of school-level resources when dealing with demanding situations at school (e.g., classroom management issues or conflicting situations with families).

In summary, findings of this research may contribute to teaching and teacher professional practices. The training and development of personal and social resources might be an effective way to sustain and retain high-quality teachers, making them less likely to quit and to perceive their work as more satisfying.

Data availabilityData will be made available on request.

Conflicts of interestNone.

This research has been funded in part by research projects from the University of Málaga and Junta de Andalucía/FEDER (UMA18-FEDERJA-147), funded projects by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (PID2020-117006RB-I00) and PAIDI Group CTS-1048 (Junta de Andalucía). The first author is supported by the University of Málaga. The second author is supported by a ‘Juan de la Cierva-Formación’ Postdoctoral Research Fellowship from the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (FJC2019-038942-I/AEI/10.13039/501100011033).

Please cite this article as: Mérida-López S, Quintana-Orts C, Hintsa T, Extremera N. Inteligencia emocional y apoyo social del profesorado: explorando cómo los recursos personales y sociales se asocian con la satisfacción laboral y con las intenciones de abandono docente. Revista de Psicodidáctica. 2022;27:168–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psicod.2020.11.005