Rapid outbreaks, wide spreads, and severe damage have characterized events in public health in China. Several significant challenges have faced the global community in the 21st century, including COVID-19, resulting in uncertainty about the future of current and future generations. In the wake of the COVID-19 Pandemic, remote working and learning (RWL) have gained more importance.

Material and methodsTwo objectives were pursued in this study. To analyze how Higher Education Academician (HEA) and students used RWL during COVID-19 and how they handled RWL challenges. This research used a quantitative approach to achieve its objectives. A total of 480 students and 394 HEA were recruited through random sampling. Data collection was carried out using two self-developed questionnaires.

ResultsRWL arrangements are satisfactory to both HEA and students. HEA and students agree that RWL relieves work stress and maximizes family time. Considering the survey results, it is evident that RWL practices are strongly supported in the era of COVID-19.

ConclusionRWL is essential to work during the COVID-19 pandemic recurrence phase. It provides non-stop working and learning to HEA and students. HEA and students highly accept RWL and favor it during the particular reoccurrence period of COVID-19. Transitioning from face-to-face instruction to a fully functional virtual (RWL) environment will require time and experience. Therefore, it is recommended that the government make a proper plan for future turmoil by drawing lessons from this unanticipated crisis and providing training programs for RWL preparation.

Los acontecimientos recientes en la salud pública en China se han caracterizado por brotes rápidos, amplias propagaciones y daños graves. Varios desafíos importantes han enfrentado la comunidad global en el siglo 21, incluido COVID-19, lo que resulta en incertidumbre sobre el futuro de las generaciones actuales y futuras. A raíz de la pandemia de COVID-19, el trabajo y el aprendizaje a distancia (RWL) han ganado más importancia.

MétodosEn este estudio se persiguieron dos objetivos. En primer lugar, analizar cómo el académico de educación superior (HEA) y los estudiantes usaron RWL durante COVID-19 y cómo manejaron los desafíos de RWL. Esta investigación utilizó un enfoque cuantitativo para lograr sus objetivos. Un total de 480 estudiantes y 394 HEA fueron reclutados a través de muestreo aleatorio. La recolección de datos se llevó a cabo mediante dos cuestionarios de desarrollo propio.

ResultadosLos arreglos de RWL son satisfactorios tanto para HEA como para los estudiantes. Tanto HEA como los estudiantes están de acuerdo en que RWL alivia el estrés laboral y maximiza el tiempo en familia. Teniendo en cuenta los resultados de la encuesta, es evidente que las prácticas de RWL están fuertemente respaldadas en la era de COVID-19.

ConclusiónRWL es esencial para trabajar durante la fase de recurrencia de la pandemia de COVID-19. Proporciona trabajo y aprendizaje sin parar a HEA y estudiantes. HEA y los estudiantes aceptan altamente RWL y la favorecen durante el período de recurrencia particular de COVID-19. La transición de la instrucción cara a cara a un entorno virtual completamente funcional (RWL) requerirá tiempo y experiencia. Por lo tanto, se recomienda que el gobierno haga un plan adecuado para la agitación futura extrayendo lecciones de esta crisis impreversa y proporcionando programas de capacitación para la preparación de RWL.

A worldwide pause in action is being called because of the COVID-19 Pandemic; due to this crisis, most academic leaders recommended online education to resolve it.1 COVID caseloads in China rarely exceeded triple digits for nearly two years, and sometimes weeks passed without a single case being recorded. Compared to the world, China's borders were opened with strict measures, and its population was largely unaffected by the virus. The situation changed recently as multiple outbreaks across the country led to the most significant increase in local infections since Wuhan's preliminary outbreak was under control in early 2020.2 Since China's COVID-19 situation has recurred, many academic institutions have arranged remote learning and working (RWL) schedules as an immediate consequence. The COVID-19 Pandemic has led universities to provide their instructors and students with online materials, usually delivered face-to-face.1

Various methods can facilitate the transition from on-campus to distance learning, including self-paced independent study, remote interactive workshops, or real-time immersive environments.3 Although previous international research studies4–9 have contributed to a better understanding of RWL. However, to our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate Higher Education Academician (HEAs) and students' experiences and challenges of RWL, particularly in China's higher education, during COVID-19's recurrence phase. We believe the current detailed state-of-the-practice study will serve as a body of knowledge for practitioners and academic researchers in higher education. In addition, the findings of this study will provide a prioritization-based taxonomy of the investigated best practices, which assists the practitioners in considering the most effective best practices on a priority basis. This study involved two separate yet interdependent groups of stakeholders, namely HEA and students. Considering the impacts identified in the literature, examining how universities, HEA, and students in China have coped with COVID-19 and RWL during the Pandemic. The following aims were devised:

- 1

To assess HEA and students' experiences regarding RWL effectiveness.

- 2

To investigate the challenges HEA and students face in adjusting to this new working model.

- 3

To identify practical strategies for addressing the identified factors.

Globally, universities at all levels have moved traditional face-to-face instruction to online delivery during the COVID-19 Pandemic.1 Technology challenges have become key concepts in the global debate about COVID-19 and the decline of education.10 The benefits of RWL are becoming increasingly evident. It represents our work paradigm shift.6 In the last few decades, teleworking and the extent of telecommuting have steadily increased across Europe, the United States, and other parts of the world with the further advancement of ICTs.5

A systematic literature review by Calonge et al.11 examined various applications of emergency remote teaching and learning (ERTL). Developing a resilient, sustainable ERTL educational ecosystem, a risk management structure for teaching and learning, and more robust support systems for faculty and students at all levels is crucial. Finnish university employees' relatedness experiences were qualitatively examined by Tapani et al.12 during forced remote work caused by the COVID-19 Pandemic. It was investigated at the earliest stages of forced remote work (April 2020) and November/December 2021. As a result of the enforced work period, the experience of relatedness was severely challenged. A positive sense of relatedness can still be fostered by developing good remote communication and leadership practices that convey employee care.

Ho et al.13 conducted a study predicting student satisfaction with emergency remote learning (ERL) in higher education during COVID-19 using machine learning techniques; they determined the impact of Moodle and Microsoft Teams as the most important learning tools on undergraduate students' satisfaction with ERL at a private university in Hong Kong. Face-to-face learning is preferred over ERL, even though many students have no problem accessing learning devices or Wi-Fi. This is the most important predictor of students' academic success. Students' satisfaction scores are highly influenced by instructor effort, the effectiveness of the adjusted assessment methods, and the perception of online learning. To be effective at remote teaching, one must be organized, set up an adequate home office, maximize productivity, facilitate communication and network, balance, use available computer programs and platforms, and be creative. Using preventive telerehabilitation methods and learning from the challenges to help the homebound, including exploring remote research options.14–16

This study explains different aspects of HEA's and students' academic and social lives using all these precautionary and preventive measures. The present study investigates how the COVID-19 outbreak in China has affected HEA and students, specifically in health education. There is a need to research RWL in academic settings, and this study was conducted to fill some gaps in the literature.

Materials and methodsResearch designA cross-sectional survey design17 was used for data collection between October and November 2022 via online Microsoft-based questionnaires.

Participants and procedureThe target population includes all HEA students from public and private higher education institutions in Shaanxi Province, China. A simple random sampling technique was utilized to ensure accurate data analysis, in which each individual has an equal chance of being selected from the population.1 An online Open-Epi calculator (Sample Size Calculator for Estimating a Proportion (statulator.com) was used to determine the sample size for the present study. A sample size of 385 is required for a 95% confidence level and 5% exact precision when 50% of the target population subjects are interested in participating.18

InstrumentsTwo instruments were used to collect the data from HEA and students. These were developed from previous literature.

Instrument 1: Higher Education Academician Working from Home (HEAWH)HEAWH consists of 29 items, including one multiple-choice question about work symptoms and experiences and one open-ended question. The questionnaire explored the following themes:

- (1)

Socio-demographic data were collected using an ad-hoc questionnaire1

- (2)

Remote working benefits

- (3)

Challenges of working

- (4)

Open-ended: "What else would you like to share? Please feel free to write whatever you want?"

SLFH consists of 27 items, including one multiple-choice question about work symptoms and one open-ended question. As part of the questionnaire, we explored the following themes:

- (1)

Socio-demographic data were collected using an ad-hoc questionnaire (1)

- (2)

Remote learning benefits

- (3)

Challenges of remote learning

- (4)

Open-ended: "What else would you like to share? Please feel free to write whatever you want?"

A five-point Likert scale ranging from five (definitely agree) to one (definitely disagree) was attached to both questionnaires. In order to determine the internal consistency of items, Cronbach's alpha was used. Cronbach's α values were 0.84 for the RL benefits and 0.83 for the challenges of RL. Generally, a reliability coefficient of between +0.3 and 0.69 indicates a moderate level of reliability, while a coefficient of between +0.7 and 1 indicates a strong level of reliability.19

Data collection & data analysisMicrosoft Forms were used to create both surveys, and the link was distributed by e-mail to higher education institutions' administrations. Microsoft Forms data were exported for statistical analysis using IBM SPSS version 25. The Shapiro-Wilk and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests were applied to determine if the data were normally distributed.20 A Gaussian distribution was observed in the data set. Using descriptive analysis, each scale's means and standard deviations were determined, and the frequency of the categorical variables was gauged. A t-test was used to investigate the gender differences in RWL experiences between HEA and students. The open-text responses were categorized using a qualitative data analysis method of content analysis.

Ethical considerationsAll ethical norms are observed in this study. On the first page of the online questionnaire, participants were provided with information about the study and invited to agree to participate by signing the consent form. Participants were asked to participate in the survey voluntarily. Before the survey began, they were informed that the data would be kept confidential and used only for research purposes. Furthermore, no personally identifiable information was collected from the participants.

ResultsDemographics statisticsHEAA total of 394 HEAs representing higher education institutions participated in this study. Most of the 204 (51.7%) participants were female. Most respondents (n = 312; 79.1%) were older than 30. The three most common disciplines of working among participants were health science (n=209; 53.1%), arts & humanities (n=100; 25.3.8%), and applied sciences (n=85; 21.6%). There were both Chinese and international HEAs involved in the study. The most significant proportion of participants hailed from China, 290 (73.6%). Notably, over half of the HEA (n = 215, 54.5%) mentioned their current residence as their hometown.

StudentsA total of 480 students from different higher education institutions participated in this study. Among them, 305 (63.5.7%) participants were females. Most (n = 320; 66.6%) were 18-23 years old. The three most common enrolled programs of participants were undergraduate (n=338; 70.4%), master (n=89; 18.6%), and doctoral (n=41; 8.5.6%). Chinese and international students were involved in the study, with the most significant number, 376 (78.4%), coming from China. More than half of the students (n = 215; 54.5%) live outside their hometowns.

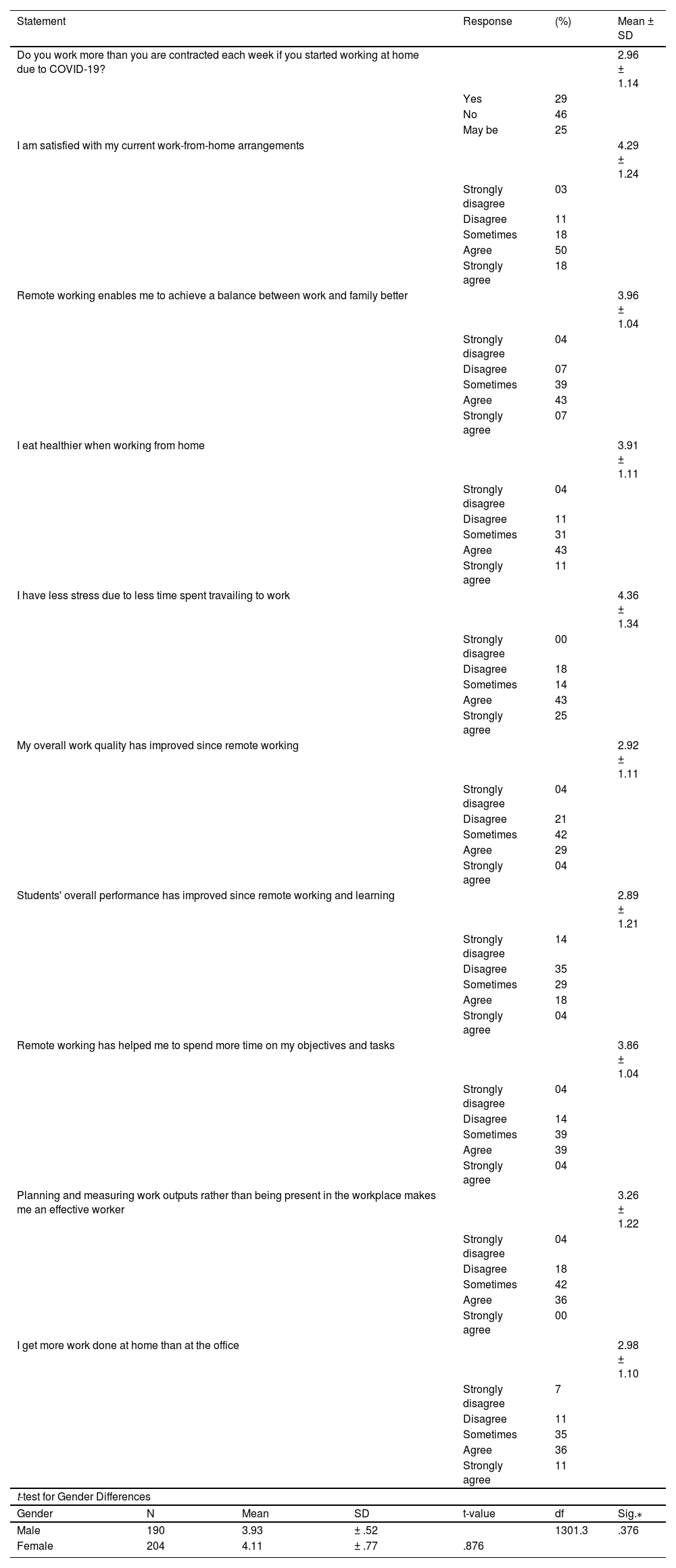

Aim 1: To assess the experiences of HEA and students regarding the effectiveness of RWLHEAHEA's experiences regarding remote working (RW) effectiveness were investigated using descriptive statistical tests, i.e., mean and standard deviation, shown in Table 1. Less stress due to less time spent travailing to work was rated above Mean= 4 by HEA. This demonstrates that HEA benefits from RW. While working more than F2F work at home due to the COVID-19 situation obtained the least mean value by HEA. Furthermore, an independent sample t-test was employed to analyze HEA perceptions of RW effectiveness. There were no gender differences in the two groups (males and females). Still, there was a statistically significant difference in the mean RW effectiveness score between males and females (Table 1), with females scoring higher M = 4.11 than males M=3.93. These findings indicate how the HEA believes RW has assisted them throughout COVID-19 in their work and personal lives.

A table displaying HEA choices on their experience of remote working.⁎

| Statement | Response | (%) | Mean ± SD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you work more than you are contracted each week if you started working at home due to COVID-19? | 2.96 ± 1.14 | |||||

| Yes | 29 | |||||

| No | 46 | |||||

| May be | 25 | |||||

| I am satisfied with my current work-from-home arrangements | 4.29 ± 1.24 | |||||

| Strongly disagree | 03 | |||||

| Disagree | 11 | |||||

| Sometimes | 18 | |||||

| Agree | 50 | |||||

| Strongly agree | 18 | |||||

| Remote working enables me to achieve a balance between work and family better | 3.96 ± 1.04 | |||||

| Strongly disagree | 04 | |||||

| Disagree | 07 | |||||

| Sometimes | 39 | |||||

| Agree | 43 | |||||

| Strongly agree | 07 | |||||

| I eat healthier when working from home | 3.91 ± 1.11 | |||||

| Strongly disagree | 04 | |||||

| Disagree | 11 | |||||

| Sometimes | 31 | |||||

| Agree | 43 | |||||

| Strongly agree | 11 | |||||

| I have less stress due to less time spent travailing to work | 4.36 ± 1.34 | |||||

| Strongly disagree | 00 | |||||

| Disagree | 18 | |||||

| Sometimes | 14 | |||||

| Agree | 43 | |||||

| Strongly agree | 25 | |||||

| My overall work quality has improved since remote working | 2.92 ± 1.11 | |||||

| Strongly disagree | 04 | |||||

| Disagree | 21 | |||||

| Sometimes | 42 | |||||

| Agree | 29 | |||||

| Strongly agree | 04 | |||||

| Students' overall performance has improved since remote working and learning | 2.89 ± 1.21 | |||||

| Strongly disagree | 14 | |||||

| Disagree | 35 | |||||

| Sometimes | 29 | |||||

| Agree | 18 | |||||

| Strongly agree | 04 | |||||

| Remote working has helped me to spend more time on my objectives and tasks | 3.86 ± 1.04 | |||||

| Strongly disagree | 04 | |||||

| Disagree | 14 | |||||

| Sometimes | 39 | |||||

| Agree | 39 | |||||

| Strongly agree | 04 | |||||

| Planning and measuring work outputs rather than being present in the workplace makes me an effective worker | 3.26 ± 1.22 | |||||

| Strongly disagree | 04 | |||||

| Disagree | 18 | |||||

| Sometimes | 42 | |||||

| Agree | 36 | |||||

| Strongly agree | 00 | |||||

| I get more work done at home than at the office | 2.98 ± 1.10 | |||||

| Strongly disagree | 7 | |||||

| Disagree | 11 | |||||

| Sometimes | 35 | |||||

| Agree | 36 | |||||

| Strongly agree | 11 | |||||

| t-test for Gender Differences | ||||||

| Gender | N | Mean | SD | t-value | df | Sig.⁎ |

| Male | 190 | 3.93 | ± .52 | 1301.3 | .376 | |

| Female | 204 | 4.11 | ± .77 | .876 | ||

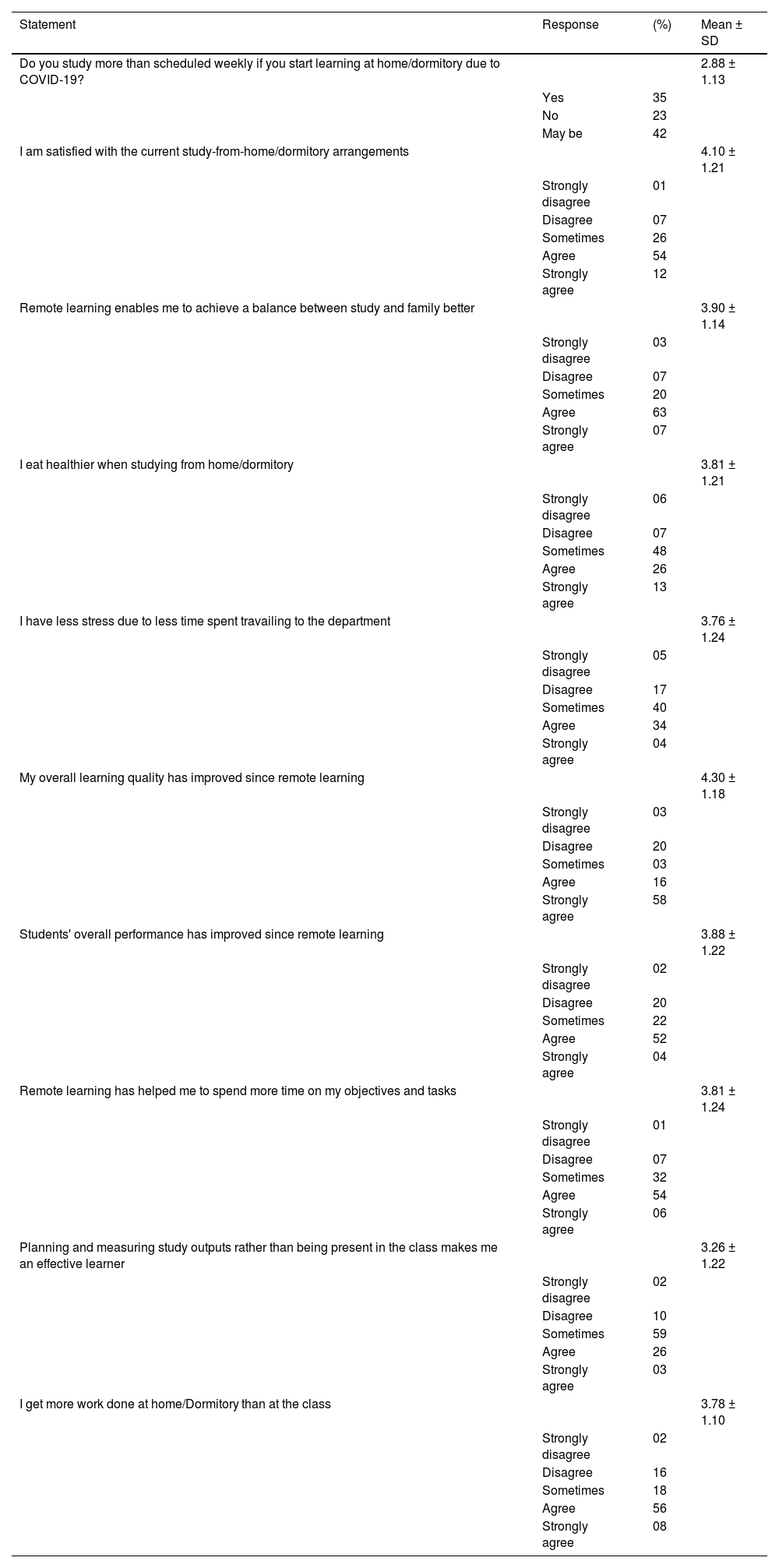

Students' experiences regarding remote learning (RL) effectiveness were investigated utilizing descriptive statistical tests, i.e., mean and standard deviation, shown in Table 2. Overall, learning quality has improved since RL was rated above M= 4 by students. While studying more than F2F classes at home due to the COVID-19 situation obtained the least mean value. The effectiveness of RL was also examined using an independent sample t-test. The variances for males and females did not differ according to gender. The effectiveness of RL was rated differently by males and females (Table 2), with females scoring higher M = 4.03 than males M=3.90. In COVID-19, the students found that RL helped them both in their educational and personal lives. Female Students, in particular, were more willing to accept RL.

A table displaying students' choices on their experience of remote learning.⁎

| Statement | Response | (%) | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Do you study more than scheduled weekly if you start learning at home/dormitory due to COVID-19? | 2.88 ± 1.13 | ||

| Yes | 35 | ||

| No | 23 | ||

| May be | 42 | ||

| I am satisfied with the current study-from-home/dormitory arrangements | 4.10 ± 1.21 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 01 | ||

| Disagree | 07 | ||

| Sometimes | 26 | ||

| Agree | 54 | ||

| Strongly agree | 12 | ||

| Remote learning enables me to achieve a balance between study and family better | 3.90 ± 1.14 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 03 | ||

| Disagree | 07 | ||

| Sometimes | 20 | ||

| Agree | 63 | ||

| Strongly agree | 07 | ||

| I eat healthier when studying from home/dormitory | 3.81 ± 1.21 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 06 | ||

| Disagree | 07 | ||

| Sometimes | 48 | ||

| Agree | 26 | ||

| Strongly agree | 13 | ||

| I have less stress due to less time spent travailing to the department | 3.76 ± 1.24 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 05 | ||

| Disagree | 17 | ||

| Sometimes | 40 | ||

| Agree | 34 | ||

| Strongly agree | 04 | ||

| My overall learning quality has improved since remote learning | 4.30 ± 1.18 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 03 | ||

| Disagree | 20 | ||

| Sometimes | 03 | ||

| Agree | 16 | ||

| Strongly agree | 58 | ||

| Students' overall performance has improved since remote learning | 3.88 ± 1.22 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 02 | ||

| Disagree | 20 | ||

| Sometimes | 22 | ||

| Agree | 52 | ||

| Strongly agree | 04 | ||

| Remote learning has helped me to spend more time on my objectives and tasks | 3.81 ± 1.24 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 01 | ||

| Disagree | 07 | ||

| Sometimes | 32 | ||

| Agree | 54 | ||

| Strongly agree | 06 | ||

| Planning and measuring study outputs rather than being present in the class makes me an effective learner | 3.26 ± 1.22 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 02 | ||

| Disagree | 10 | ||

| Sometimes | 59 | ||

| Agree | 26 | ||

| Strongly agree | 03 | ||

| I get more work done at home/Dormitory than at the class | 3.78 ± 1.10 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 02 | ||

| Disagree | 16 | ||

| Sometimes | 18 | ||

| Agree | 56 | ||

| Strongly agree | 08 |

| t-test for Gender Differences | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | N | Mean | SD | t-value | df | Sig.⁎ |

| Male | 175 | 3.90 | ± .62 | 1101 | .474 | |

| Female | 305 | 4.03 | ± .67 | .776 | ||

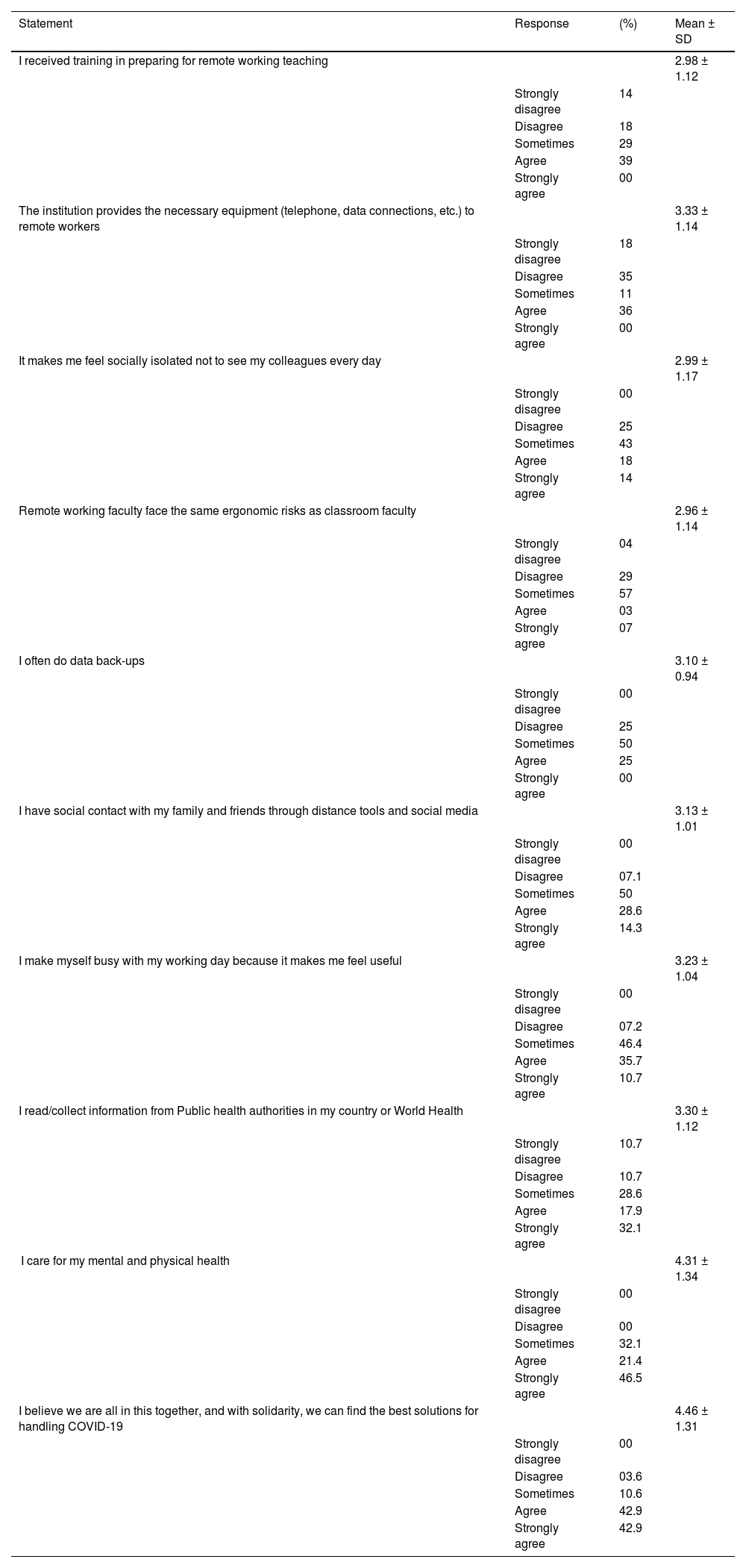

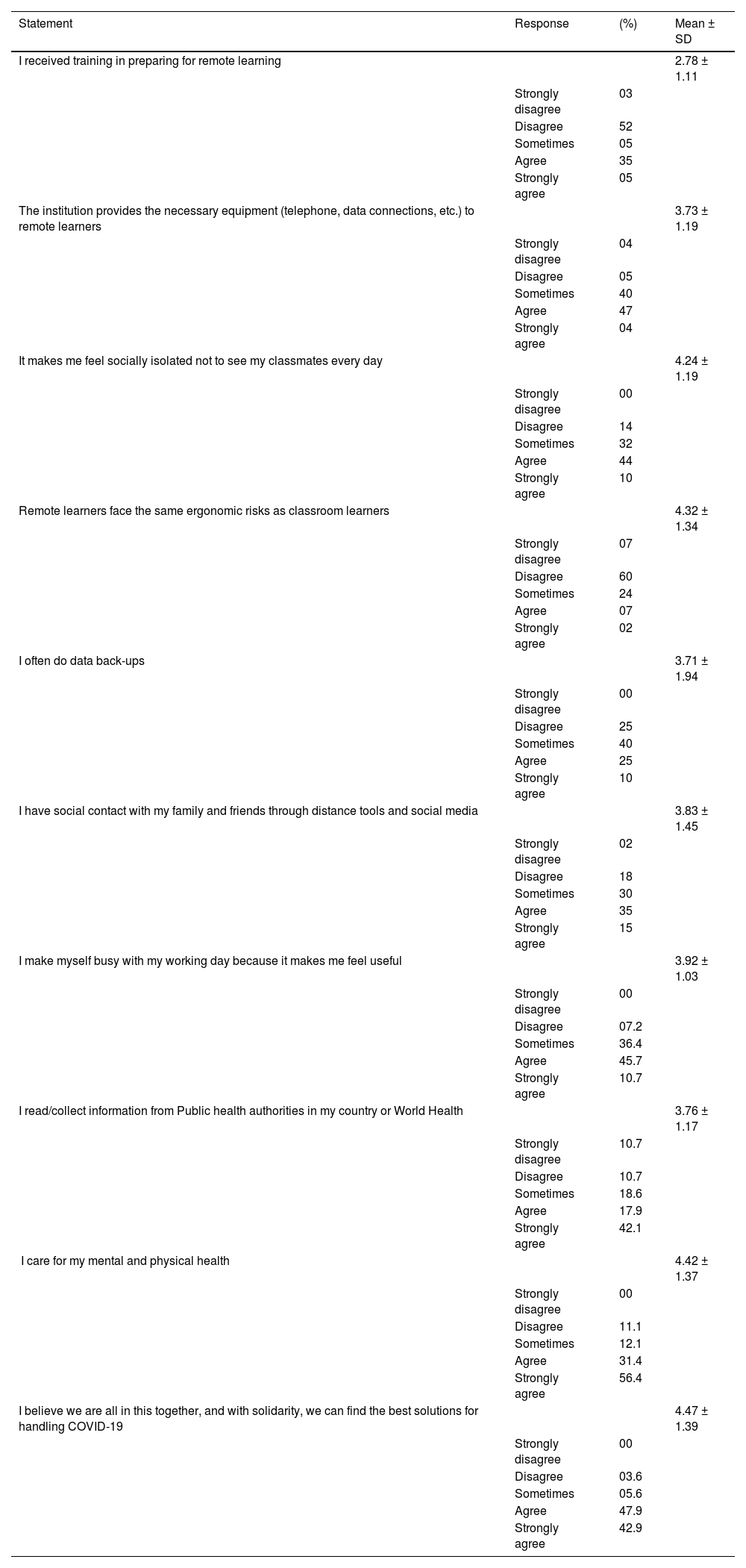

In order to examine the challenges faced by HEA and students in adjusting to this new mode of working, descriptive statistics were applied, i.e., mean and standard deviation, as shown in Tables 3 and 4. HEA and students rate the highest "I believe we are all in this together, and with solidarity, we can find the best solutions for handling COVID-19," Demonstrating that HEA and students are hopeful and following government policies. Furthermore, both rated "I received training in preparing for RWL" the least, which indicates that institutions should provide training to staff and students for better RWL.

A table displaying HEA choices on the challenges of remote working.

| Statement | Response | (%) | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| I received training in preparing for remote working teaching | 2.98 ± 1.12 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 14 | ||

| Disagree | 18 | ||

| Sometimes | 29 | ||

| Agree | 39 | ||

| Strongly agree | 00 | ||

| The institution provides the necessary equipment (telephone, data connections, etc.) to remote workers | 3.33 ± 1.14 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 18 | ||

| Disagree | 35 | ||

| Sometimes | 11 | ||

| Agree | 36 | ||

| Strongly agree | 00 | ||

| It makes me feel socially isolated not to see my colleagues every day | 2.99 ± 1.17 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 00 | ||

| Disagree | 25 | ||

| Sometimes | 43 | ||

| Agree | 18 | ||

| Strongly agree | 14 | ||

| Remote working faculty face the same ergonomic risks as classroom faculty | 2.96 ± 1.14 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 04 | ||

| Disagree | 29 | ||

| Sometimes | 57 | ||

| Agree | 03 | ||

| Strongly agree | 07 | ||

| I often do data back-ups | 3.10 ± 0.94 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 00 | ||

| Disagree | 25 | ||

| Sometimes | 50 | ||

| Agree | 25 | ||

| Strongly agree | 00 | ||

| I have social contact with my family and friends through distance tools and social media | 3.13 ± 1.01 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 00 | ||

| Disagree | 07.1 | ||

| Sometimes | 50 | ||

| Agree | 28.6 | ||

| Strongly agree | 14.3 | ||

| I make myself busy with my working day because it makes me feel useful | 3.23 ± 1.04 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 00 | ||

| Disagree | 07.2 | ||

| Sometimes | 46.4 | ||

| Agree | 35.7 | ||

| Strongly agree | 10.7 | ||

| I read/collect information from Public health authorities in my country or World Health | 3.30 ± 1.12 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 10.7 | ||

| Disagree | 10.7 | ||

| Sometimes | 28.6 | ||

| Agree | 17.9 | ||

| Strongly agree | 32.1 | ||

| I care for my mental and physical health | 4.31 ± 1.34 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 00 | ||

| Disagree | 00 | ||

| Sometimes | 32.1 | ||

| Agree | 21.4 | ||

| Strongly agree | 46.5 | ||

| I believe we are all in this together, and with solidarity, we can find the best solutions for handling COVID-19 | 4.46 ± 1.31 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 00 | ||

| Disagree | 03.6 | ||

| Sometimes | 10.6 | ||

| Agree | 42.9 | ||

| Strongly agree | 42.9 |

A table displaying students' choices on the challenges of remote learning.

| Statement | Response | (%) | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| I received training in preparing for remote learning | 2.78 ± 1.11 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 03 | ||

| Disagree | 52 | ||

| Sometimes | 05 | ||

| Agree | 35 | ||

| Strongly agree | 05 | ||

| The institution provides the necessary equipment (telephone, data connections, etc.) to remote learners | 3.73 ± 1.19 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 04 | ||

| Disagree | 05 | ||

| Sometimes | 40 | ||

| Agree | 47 | ||

| Strongly agree | 04 | ||

| It makes me feel socially isolated not to see my classmates every day | 4.24 ± 1.19 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 00 | ||

| Disagree | 14 | ||

| Sometimes | 32 | ||

| Agree | 44 | ||

| Strongly agree | 10 | ||

| Remote learners face the same ergonomic risks as classroom learners | 4.32 ± 1.34 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 07 | ||

| Disagree | 60 | ||

| Sometimes | 24 | ||

| Agree | 07 | ||

| Strongly agree | 02 | ||

| I often do data back-ups | 3.71 ± 1.94 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 00 | ||

| Disagree | 25 | ||

| Sometimes | 40 | ||

| Agree | 25 | ||

| Strongly agree | 10 | ||

| I have social contact with my family and friends through distance tools and social media | 3.83 ± 1.45 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 02 | ||

| Disagree | 18 | ||

| Sometimes | 30 | ||

| Agree | 35 | ||

| Strongly agree | 15 | ||

| I make myself busy with my working day because it makes me feel useful | 3.92 ± 1.03 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 00 | ||

| Disagree | 07.2 | ||

| Sometimes | 36.4 | ||

| Agree | 45.7 | ||

| Strongly agree | 10.7 | ||

| I read/collect information from Public health authorities in my country or World Health | 3.76 ± 1.17 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 10.7 | ||

| Disagree | 10.7 | ||

| Sometimes | 18.6 | ||

| Agree | 17.9 | ||

| Strongly agree | 42.1 | ||

| I care for my mental and physical health | 4.42 ± 1.37 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 00 | ||

| Disagree | 11.1 | ||

| Sometimes | 12.1 | ||

| Agree | 31.4 | ||

| Strongly agree | 56.4 | ||

| I believe we are all in this together, and with solidarity, we can find the best solutions for handling COVID-19 | 4.47 ± 1.39 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 00 | ||

| Disagree | 03.6 | ||

| Sometimes | 05.6 | ||

| Agree | 47.9 | ||

| Strongly agree | 42.9 |

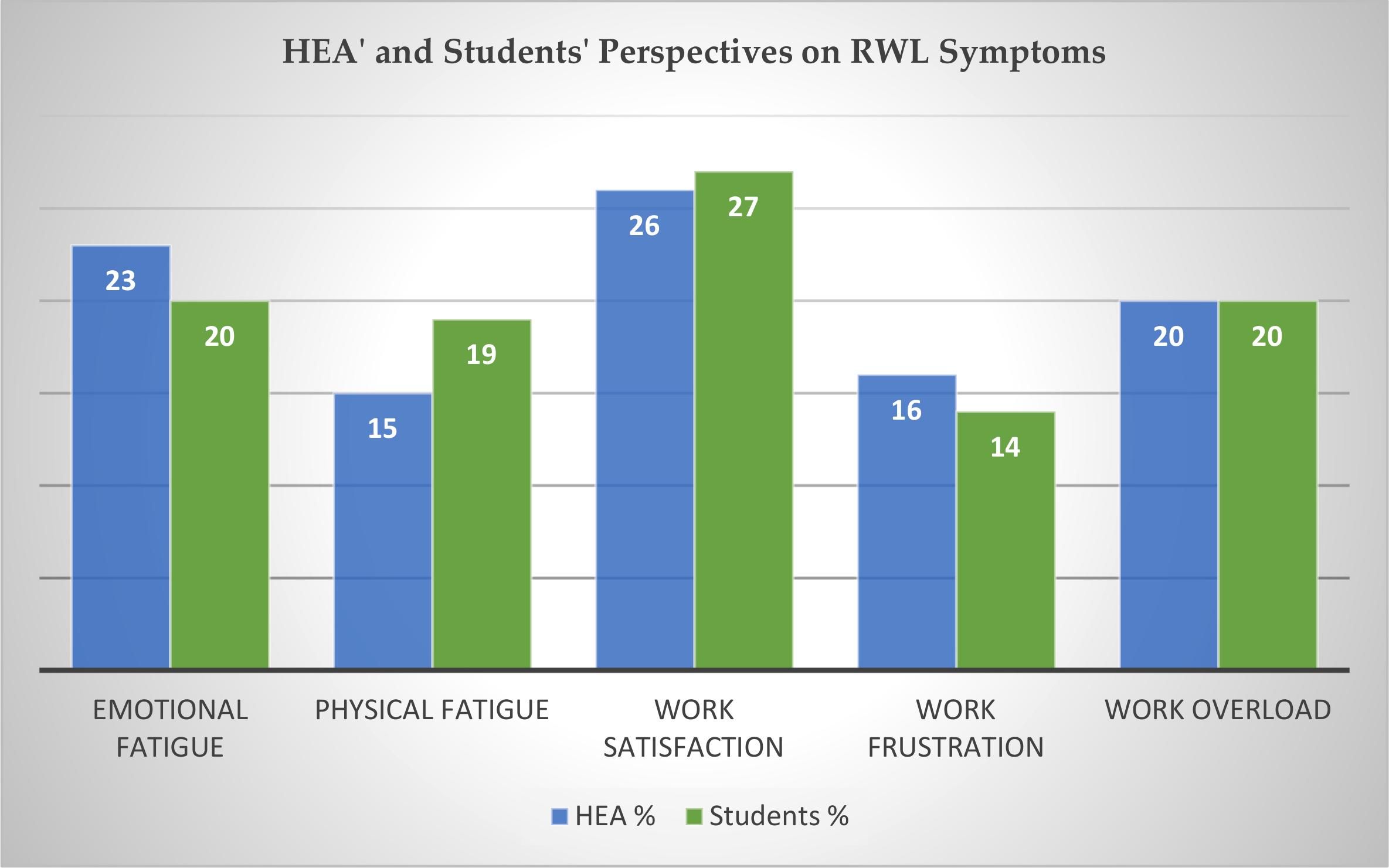

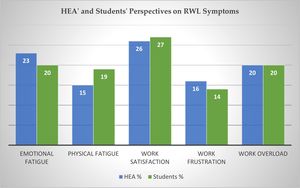

Based on the findings presented in Figure 1, HEA and students with RWL arrangements report less work frustration. When reflecting on satisfaction, respondents confirmed that remote workers and learners are more satisfied with RWL.

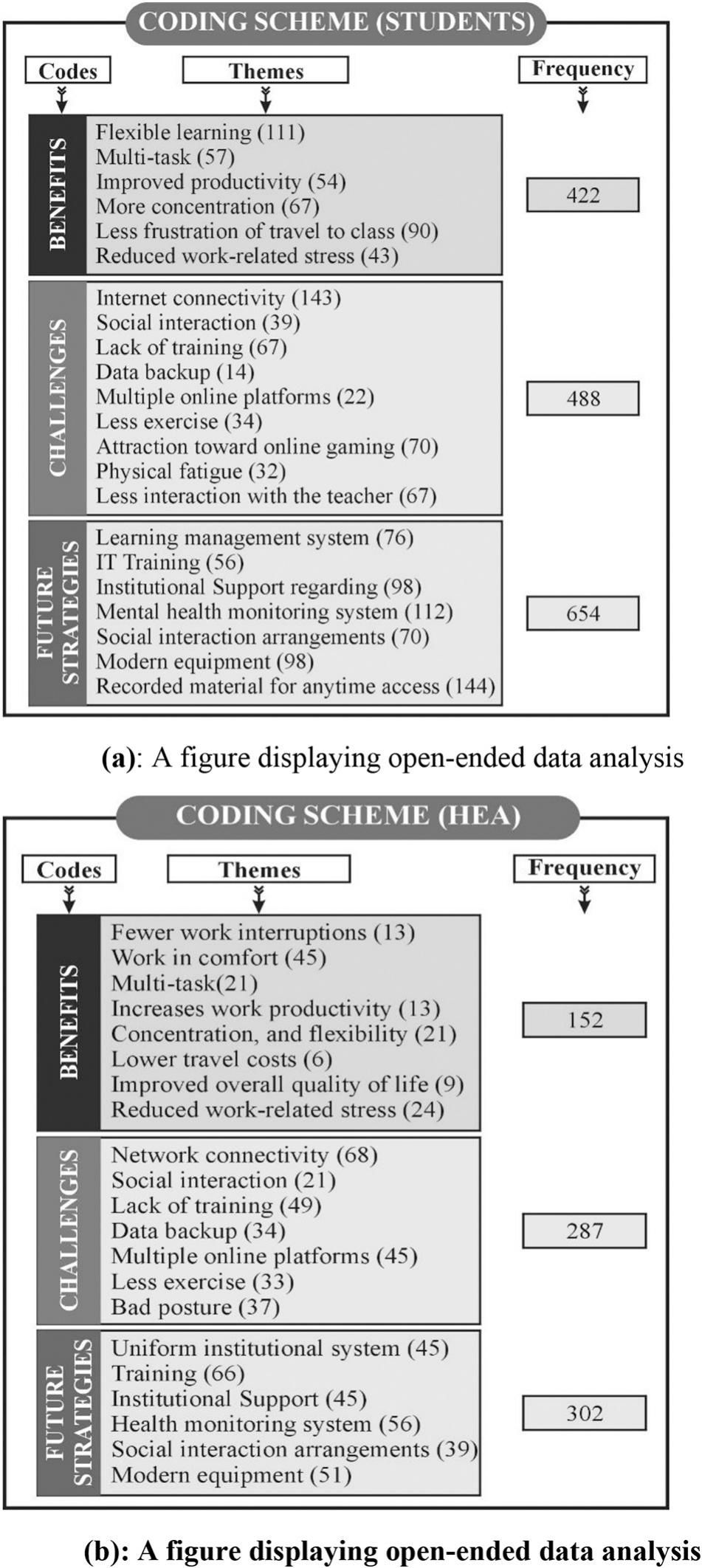

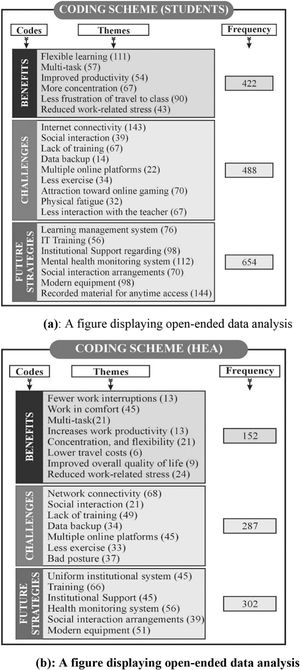

Aim 3: Identify practical strategies for addressing the identified factorsOptional open-ended questions collected HEA's and students' perspectives on improving RWL and future strategies. It was addressed by 214 (44.58%) students and 111 (28.17%) HEA. Data were coded according to a systematic procedure. Fig. 2a & 2b show three main codes, themes, and frequency. It shows that students and HEA revealed the benefits, challenges, and future RWL strategies.

DiscussionIn the wake of the COVID-19 Pandemic, many educational institutions have adopted and implemented online learning platforms.21,22

The experiences of HEAs and students regarding the effectiveness of RWLCOVID-19 has changed traditional educational practices worldwide, and teaching and learning are now conducted digitally.23 In light of this transformation, integrating educational technology into practices is necessary for the students and faculty to ensure sustainability. Considering the survey results, it is evident that RWL practices are strongly supported in the era of COVID-19. In the opinion of HEA and students alike, RWL practices can create an enduring, productive, flexible, and happy workforce. Furthermore, they seem very optimistic about RWL alleviating work stress and maximizing time spent with family. This indicates that RWL provides benefits to both HEA and students. The results of this study agree with those of previous studies.9,14–16,24

The challenges faced by HEAs and students in adjusting to this new mode of workingInstitutions seeking to expand RWL face several critical challenges related to infrastructure support aspects.25 HEA and students were concerned about solutions for handling COVID-19 and arrangements for RWL. Several studies have noted that virtual learning requires a robust hardware and software system to ensure reliable access to content and resources.26 Furthermore, training in preparing for RWL is missing. This indicates that institutions should train HEAs and students in better RWL practices. Previous studies also support these findings.9,24,27–30

Practical strategies for addressing the identified factorsIn order to create successful online pedagogy practice policies in the face of the current pandemic climate, HEA and students emphasize a shared, harmonized, and international effort. Implement a system that addresses the ergonomics of remote offices by setting up the necessary computer equipment and setups for telecommuters.1,4,9,31,32 A suitable RWL environment, family cooperation with the RWL, a reduced workload, appropriate technology for RWL, and training and preparing people for RWL can eliminate RWL problems and help them do so their job better.33 However, since RWL is still a relatively new concept in academic health settings, efforts should be put into identifying effective and efficient teaching methods that will enable HEA and students to benefit from RWL.

ConclusionUsing RWL during the recurrence phase of the COVID-19 pandemic is imperative. HEA and students benefit from non-stop working and learning. RWL is highly accepted and preferred by HEAs and students during the COVID-19 reoccurrence period. Transitioning from face-to-face instruction to a fully functional virtual (RWL) environment will require time and experience. To prepare for future turmoil, the government should draw lessons from this unexpected crisis and provide training programs for RWL candidates.

Funding statementN.A

EthicsThe present study has been conducted according to the principles of the declaration of Helsinki. The study was not subject to ethical approval. The research presents minimal risk of harm to participants. This is because it is a non-interventional study (survey). However, informed consent was obtained from the participants. Respondents' anonymity was assured during the research, and no personal information was gathered.

The authors thank UNITAR International University for the support of the publication of this research.