To identify the number of Chinese graduates from medical schools in China with an English Parallel course through a Freedom of Information search of the current UK medical register.

MethodA Freedom of Information request was submitted to the General Medical Council to investigate the number of graduates from Chinese medical schools with MB BS courses using English as the medium of instruction.

ResultsDetails of 73 graduates were obtained. Twenty one of the registrants were Chinese and 52 South Asian. During the last decade there has been a significant increase in the number of Pakistani and Indian graduates who have registered with the GMC compared to Chinese graduates.

ConclusionIf the experience with Central and Eastern European “English Parallel” courses is repeated we should expect a significant growth in the numbers of British and EU citizens training and graduating in China and subsequently practicing in the UK.

Identificar, a través de una búsqueda autorizada (Libertad de Información: Freedom of Information) en el Registro Médico del Reino Unido, el número de graduados chinos procedentes de las Facultades de Medicina chinas con un curso paralelo en inglés.

MétodoUna solicitud de Libertad de Información se presentó al Consejo General de Médicos (GMC), para investigar el número de egresados de las Facultades de Medicina chinas con cursos BS MB que utilizan el inglés como lenguaje de instrucción.

ResultadosSe obtuvieron datos de 73 egresados. Veintiuno de los registrados fueron chinos y 52 del sur de Asia. Durante la última década ha habido un aumento significativo en el número de graduados paquistaníes e hindúes que se han registrado en el GMC en comparación a los graduados chinos.

ConclusiónSi se repite la experiencia con cursos de «Inglés Paralelo» de la Europa Central o del Este, debemos esperar un crecimiento significativo en el número de británicos y ciudadanos de la UE formados y graduados en China, que posteriormente practiquen en el Reino Unido.

Nothing was previously known of the numbers or origins of graduates from Chinese medical schools with “English Parallel” courses. There are currently 73 such graduates in the UK of whom 53 are South Asian.

Effect on policyIt is likely that there will be a significant growth in the number of South Asian and British graduates from these Chinese schools. An underlying reason will be the fact that the courses and associated accommodation are “cheap” compared with those in Europe.

IntroductionIt has recently been suggested that every year more than 10,000 international students go to China to study medicine, many selecting an English-medium MBBS degree. From 2007 the Ministry of Education has issued regulations for the “Provisions for Quality Control Standards on Undergraduate Medical Education in English for International Student in China” which have guided up to 50 schools recognised for such teaching. For British and other EU citizens provided that these schools are listed in the Avicenna Directory for Medicine, the World Directory of Medical Schools or the International Medical Education Directory and certain other criteria are met then graduation from one of these institutions entitles full registration in the UK with the General Medical Council (GMC) without the requirement of formal further assessment.1 The emergence of a significant number of additional centres which provide medical education through the medium of English will ultimately have an impact on the number of junior doctors entering the British job market.

One of the attractions of training in China has been the low cost of the programmes. This has proven particularly so for students from India with more than 7000 currently at a Chinese medical school. Although Indian and Pakistani graduates from these medical schools will be required to follow the standard pathway of all non-EU citizens it is likely some will ultimately choose to work in the UK. The cost of training at the UK's first private medical school at the University of Buckingham will be about £35,000 per year.2 This compares with £4500 per year including accommodation. In other words a six year complete training programme including accommodation at a leading Chinese medical school will cost less than one year at the University of Buckingham and will convey the same rights of practice in the UK for British and EU citizens.

During the last twenty years there has been a singular failure to recognise the role of “English Parallel” courses in medical schools in Central and Eastern Europe with growing numbers of British citizens qualifying in medicine, dentistry and veterinary medicine.3,4 Most of these graduates have returned to work in the UK. This contrasts with the approach of countries, such as Norway, which endeavours to maintain formal links with its citizens training in other countries.5 As a result it can better plan the utilisation of such graduates. Indeed there is good reason to encourage bodies such as the GMC and the Centre for Workforce Intelligence to develop strategies to monitor the numbers of British citizens training outside of the UK. The introduction of some potential benefits to such students might encourage them to come forward and register centrally.

In both India and Australia the term “Made in China” is now commonly used in some parts of the press when discussing medical manpower. The purpose of this study was to assess the likelihood that the emergence of significant numbers of Chinese medical schools with English based training might, in the next decade, significantly add to the number of junior doctors seeking posts in the UK.

MethodsUnder a Freedom of Information (F14/6537) request the General Medical Council was asked to provide details of registered practitioners from the following universities in China:

Nankai University

Xinjiang Medical University

Tianjin Medical University

Wenzhou Medical College

West China School of Medicine

Sichuan University

Xian Jiaotong University

Zhejiang University

Fudan University

Sun Yat-Sen University

Wuhan University

Capital Medical University

Quingdao University

Huazhong University of Science and Technology

Tongi Medical University

China Medical University

Guangzhou Medical University

Jinan University

Ningbo University

Southern Medical University

Details of names, date and place of qualification as well as time of registration with the GMC up until 2nd September 2014 were provided.

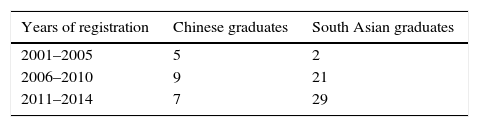

ResultsDetails of 73 graduates were provided under the FOI request. Twenty one of the registrants were Chinese and 52 South Asian. Of the doctors registered with the GMC 14 Chinese and 5 South Asian doctors had graduated in China between 1986 and 2000 from one of these universities (Table 1). The composition of this group differs significantly to those who qualified after 2000 and subsequently registered with the GMC. Amongst this group there were many more South Asian graduates (χ2=54.8, p<0.0001).

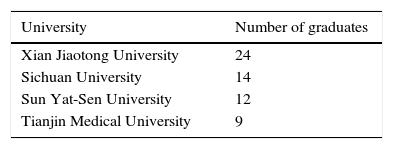

The majority of graduates came from one of 4 schools, with Xian Jiaotong University the most popular (Table 2). It is under the direct jurisdiction of the Ministry of Education and has been singled out to become a world class university. Sichuan claims that most of its English Medium Faculty trained in the USA or Canada.

DiscussionDuring the last decade there has been a significant growth in the number of medical students from India and Pakistan who have trained at Chinese medical schools through the medium of English. This growth has been paralleled by a significant increase in the number of such doctors who have registered with the GMC. In contrast registration by Chinese doctors from these medical schools has remained at a constant level. It seems likely that we will continue to see an increase in the number of registrants who have qualified from Chinese medical schools with courses conducted in the medium of English. With the low cost of such courses it seems likely that we will see more and more EU nationals who have studied at such universities.

In order to ensure a high quality standard the Chinese Ministry of Education requires that:

- 1.

The course duration for MBBS in English medium for foreign students is 6 years. The sixth year is an internship which can be completed either in Chinese hospitals or in a hospital in the home country recognised by the Ministry of Health of the concerned country.

- 2.

Chinese language is compulsory during the whole course of study along with the MBBS course in the English medium in order to ensure good communication with Chinese patients. In order to do an internship in China, it is mandatory that a student passes the Chinese language proficiency exam known as HSK.

- 3.

The Medical Education Expert Group assesses the teaching quality of the undergraduate medical education programme in English for international students and publishes the list of accepted institutions and scale of their admissions annually. Exclusion from the list means that the Institutions will not be allowed to enrol international students for the undergraduate medical programme in English.6

At present there is little information available on the experiences of medical students on English parallel courses in China. This contrasts with the situation in Central and Eastern Europe where student blogs give a depth and richness to our understanding of their experiences.7 Only one student blog is easily accessible, that of Henry Davies.8 He describes “tough exams every six months” and attributes the reason to: “Chinese students are very hard working, which has a good effect on the international students. It means our course is tough and there is a lot to learn.” “get other students to study in China.” “Language is the main problem. Some teachers are really good; they can explain everything… They know everything, but they don’t know how to explain it in English.”

Confirmation comes from a report by Aiyar after her visit to Tianjin in 2006. At the time there were about 250 Indian students at the medical school. Despite the Dean's reassurance of high standards for admission and the fluency in English of the lecturers this was not her experience. At the solitary class she attended she wrote the “English was incomprehensible”.10

The limited data on the standards of teaching in English Parallel courses at Chinese medical schools needs further study. For non-EU citizens the requirements for registration will mean that only graduates who are fluent in English will successfully negotiate the International English Language Testing System (IELTS) and Professional and Linguistic Assessments Board (PLAB). However, for EU graduates fluency in English and clinical skills will only be challenged through “Fitness to Practice” issues.

FundingThis research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interestThe author has no conflicts of interest to declare.