One of the adopted measures during the Coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in education is the online modality, which can impact students' quality of Life (QoL) and their academic performance.

MethodsThis cross-sectional study aims to assess the impact of online education on health-related QoL in a sample of 401 medical students.

ResultsMost students attended all the online sessions, and around 32% participated in some of them. Only 16.2% reported high satisfaction from the online sessions, and almost 39% reported low satisfaction. Overall, medical students had moderate QoL. Online education affected medical students psychologically more than physically, translated by higher scores for the physical components than the mental ones. Students who preferred online over in-person education had significantly lower scores for the mental domains, namely lower social functioning and emotional role scores. Academic satisfaction did not influence any SF-36 scores, and students’ preferences (online or in-person education) did not affect any of the physical component scores.

ConclusionThe pandemic directly impacted the QoL of medical students, namely their mental health. Medical students in Lebanon had a higher preference for in-person education, possibly due to its novelty and to other technological, technical, or personal challenges. Future research exploring the reasons and viable solutions should be performed to maintain a steady level of education during unanticipated situations.

Una de las medidas adoptadas durante la pandemia de la enfermedad por Coronavirus de 2019 (COVID-19) en la educación es la modalidad en línea, la cual puede impactar la calidad de Vida (CdV) de los estudiantes y su rendimiento académico.

MétodosEste estudio transversal tiene como objetivo evaluar el impacto de la educación en línea en la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud en una muestra de 401 estudiantes de medicina.

ResultadosLa mayoría de los estudiantes asistieron a todas las sesiones en línea y alrededor del 32% participó en algunas de ellas. Solo el 16,2 % reportó una alta satisfacción con las sesiones en línea y casi el 39 % reportó una baja satisfacción. En general, los estudiantes de medicina tenían una CdV moderada. La educación en línea afectó a los estudiantes de medicina psicológicamente más que físicamente, lo que se traduce en puntajes más altos para los componentes físicos que para los mentales. Los estudiantes que preferían la educación en línea a la presencial tenían puntajes significativamente más bajos en los dominios mentales, es decir, puntajes más bajos en el funcionamiento social y el rol emocional. La satisfacción académica no influyó en ningún puntaje del SF-36, y las preferencias de los estudiantes (educación en línea o en persona) no afectaron ninguno de los puntajes del componente físico.

Conclusiónla pandemia impactó directamente en la CdV de los estudiantes de medicina, es decir, en su salud mental. Los estudiantes de medicina en el Líbano tenían una mayor preferencia por la educación presencial, posiblemente debido a su novedad y a otros desafíos tecnológicos, técnicos o personales. Se deben realizar investigaciones futuras que exploren las razones y las soluciones viables para mantener un nivel constante de educación durante situaciones imprevistas.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, university students' Quality of Life (QoL) was negatively affected with increased reported mental health problems, including depression and anxiety.1 Previous research assessing the mental health of university students reported a high prevalence of psychological symptoms that were exacerbated by the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic.2 Social isolation, anxiety, ambiguity, chronic stress, and economic hitches could have worsened the stress-related conditions, particularly among those with pre-existing psychological disorders, low resilience, and those more affected by the pandemic.3

In response to the virus’s rapid spread, universities were closed, resulting in a rapid shift from in-person to online education. Several benefits of distance learning were previously reported, such as ensuring the continuity of education,4,5 ensuring lifelong learning,6,7 and reducing the high costs associated with traditional education.8 Nevertheless, this new mode of education imposed new challenges due to social inequalities among students, namely accessing the internet and other technical supports.9 Limitations were also noted regarding teaching methods and schedule adaptation.10 However, the impact of online education was not limited to the education system since it affected the student’s learning experience and academic performance.11 Research published in 2019 showed that online education might affect the chances of students being employed after graduation, given that many job markets do not accept online degrees.12 Furthermore, the online mode of education affected students' physical health since physical inactivity increased due to decreased outdoor activity and increased screen time spent on computers or electronic devices.13 As a result, there is a special concern regarding the increased risks of metabolic and cardiovascular diseases associated with physical inactivity.14,15

The possible depreciation of students’ mental and physical health due to the pandemic and online education may adversely affect their QoL.16 Many reports highlighted the need to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the corresponding changes on the health-related QoL of healthy populations.13,17 In particular, university students may be more sensitive to these changes due to several reasons, such as the suspension of schools, social distance measures, and social communication limitations.18 Thus, this study aims to assess the impact of online education on the health-related QoL of medical students in Lebanon.

Material and methodsStudy designAn observational cross-sectional study was conducted over a period of three months (August-October 2021), targeting university students from different medical schools in Lebanon. The study protocol, survey, and consent form were reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of the faculty of pharmacy at the Lebanese University (reference 22/D/7).

Study sample and sample sizeStudents were recruited from four faculties: public health, medical sciences, dentistry, and pharmacy. These faculties were in both public (Lebanese university) and private universities (Lebanese American University, American University of Beirut, Saint Joseph University, Beirut Arabic University, and the University of Balamand). No criteria were based on sex, nationality, age, and ethnicity. Nevertheless, students refusing to participate were excluded from the study. The sample size was determined using the Epi Info 7 software. As there were no similar studies related to coronavirus disease, the calculation assumed that the probability of having good mental and physical health was 50%. Considering a 95% confidence interval and a 5% acceptable margin of error, at least 386 participants were required, with a 5% loss to follow-up.

Data collectionTwo pharmacists approached students from different faculties. They explained the study’s aims orally and invited them to participate by filling out an online survey. The first page of the survey included the study’s aims (written), the estimated time to answer the questionnaire (12–15 minutes), statements on the anonymity and confidentiality of their responses, and consent to use their data for research purposes only. Participation in the survey was strictly voluntary.

Study toolAfter an extensive literature review, a validated questionnaire was used for data collection (Supplementary material).19 It was available in English and Arabic, depending on the student’s preferences. The first part included questions about the general characteristics of the participants (sex, age (≤30 or >30), the governorate of residence (including the eight governorates in Lebanon), marital status, type of the university (public or private), faculty (public health, medical sciences, dentistry or pharmacy) and the academic year. In the second part, students were asked five questions about the characteristics of online education (frequency of attendance, if the online sessions included practical and theoretical work if they felt that online education provided them with sufficient information, satisfaction with the sessions, and preferences between online and in-person education). In the last part, The 36-item Short Form (SF-36) survey (validated on Lebanese university students) was used,19 and the corresponding answers were afterward graded over 100. These questions will generate eight subscales: physical functioning (PF), physical role (RP), bodily pain (BP), general health (GH), vitality (VT), social functioning (SF), emotional role (ER), and mental health (MH). The first four scores lead to the physical composite score (PC), while the last four can be summed to create the mental composite score (MC). A minimum score of 0 represents the lowest QoL, and a maximum of 100 represents the highest.

Statistical analysisStatistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois) Version 27. Categorical variables are presented through frequencies and percentages. These variables included the general characteristics of the students and the questions related to the characteristics of online education. The different scores are presented through means and standard deviations. Individual SF-36 items were recorded, summed, and transformed as recommended.20 One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to assess the relationship between the SF-36 scale scores and questions related to online education. A multivariate analysis was performed using linear regression models to evaluate the combined effect of predictors (online education variables) on SF-36 dimensions. The confusion variables (or covariates) were those related to the characteristics of online education. They were considered if they had a statistically significant p-value (<0.05) in the ANOVA analysis.

ResultsGeneral characteristics of the studentsOverall, 424 students were approached, and 401 agreed to participate in the study (94.6%). The general characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 1. The sample consisted of 45.9% of men and 54.1% of women. Most of the students were less than 30 years of age (93.3%). Participants were distributed in the different governorates, with Mount Lebanon (19.7%), Beirut (16.7%), Nabatiyeh (13.2%), and Akkar (12.7%) accounting for the highest percentages. Among the students, 83% were single, and the rest were either married or engaged. Almost a third of the participants were from public universities, and 68.6% studied in private universities. Regarding distribution among faculties, 32.9% were from the faculty of public health, 26.4% from the faculty of medical sciences, 20.9% from the faculty of pharmacy, and 19.7% from the faculty of dentistry. A third of the participants were in their first couple of years of studies, 41.4% were in their third or fourth year, and the rest (25.2%) were in their fifth year or more.

Distribution of the general characteristics of the students.

| Total (N=401) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Frequency (%) | ||

| Sex | Man | 184 (45.9%) |

| Woman | 217 (54.1%) | |

| Age (years) | ≤30 | 374 (93.3%) |

| >30 | 27 (6.7%) | |

| Governorate of residence | Mount Lebanon | 79 (19.7%) |

| Beirut | 67 (16.7%) | |

| Nabatiyeh | 53 (13.2%) | |

| Akkar | 51 (12.7%) | |

| South | 44 (11.0%) | |

| Bekaa | 43 (10.7%) | |

| North | 38 (9.5%) | |

| Baalbeck/Hermel | 26 (6.5%) | |

| Marital status | Single | 333 (83.0%) |

| Married/engaged | 68 (17.0%) | |

| University | Public university | 126 (31.4%) |

| Private university | 275 (68.6%) | |

| Faculty | Public Health | 132 (32.9%) |

| Medical sciences | 106 (26.4%) | |

| Pharmacy | 84 (20.9%) | |

| Dentistry | 79 (19.7%) | |

| Academic year | 1–2 | 134 (33.4%) |

| 3–4 | 166 (41.4%) | |

| 5 or more | 101 (25.2%) | |

Results are given in terms of frequency (percentage).

Table 2 presents the characteristics and students’ preferences for online education. Almost 62% of the students reported attending all the online sessions, 32.2% attended sometimes, and only 6.2% did not attend any. Around half of the sessions included both theoretical and practical work. Overall, 37.2% of the participants reported that online education provided them with sufficient information, and most (84.3%) preferred in-person over online education. As regards satisfaction with the online sessions, 16.2% of the students reported high satisfaction, 45.1% reported moderate satisfaction, and 38.7% reported low satisfaction.

Questions related to online education perception among medical students.

| Total (N=401) | |

|---|---|

| Questions | Frequency (%) |

| How much time did you attend the online sessions? | |

| All of the time | 247 (61.6%) |

| Sometimes | 129 (32.2%) |

| Never | 25 (6.2%) |

| Did online education include theoretical and practical work? | |

| Yes | 206 (51.4%) |

| Compared with in-person education, do you feel that online education provides you with sufficient information? | |

| Yes | 149 (37.2%) |

| How do you rate your satisfaction with the online sessions? | |

| High satisfaction | 65 (16.2%) |

| Moderate satisfaction | 181 (45.1%) |

| Low satisfaction | 155 (38.7%) |

| Do you prefer online education or in-person education? | |

| Online Education | 63 (15.7%) |

| In-person Education | 338 (84.3%) |

Results are given in terms of frequency (percentage).

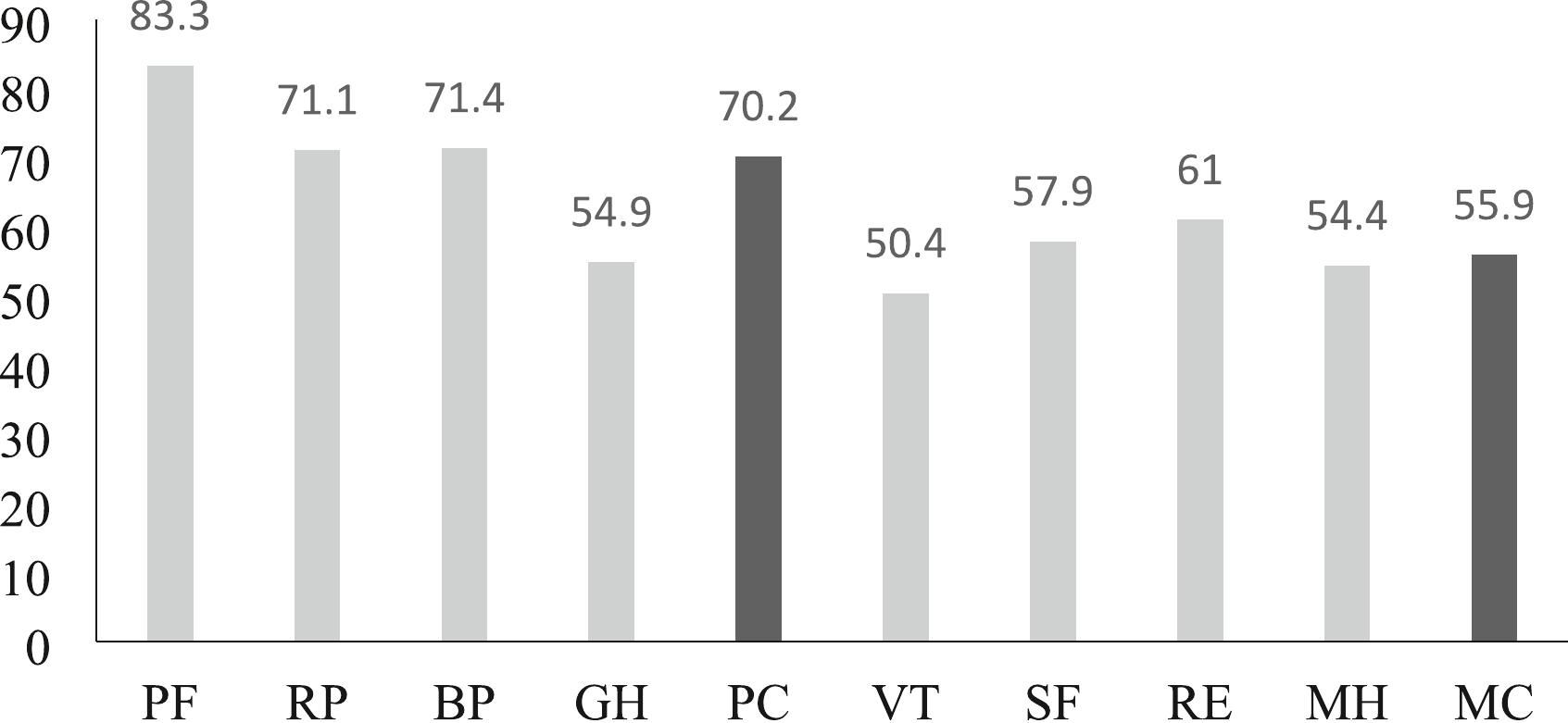

All scales had a high level of internal consistency reliability coefficient. The median values were 73.7 and 56.7 for PC and MC, respectively. Fig. 1 represents the mean value of the eight scales and the mean values of the physical and mental components. The physical functioning scale had the highest mean (83.3), while the vitality and mental health scales had the lowest mean (50.4 and 54.4, respectively). Compared to the mental components, physical components had a higher mean (70.2 versus 55.9).

Mean values of the different health-related quality of life scores of medical students in Lebanon

PF: Physical Functioning, RP: Role Physical role, BP: Bodily Pain, GH: General Health, PC: total Physical component, VT: Vitality, SF: Social Functioning, ER: Emotional Role, MH: Mental Health and MC: total Mental Component.

Table 3 shows online education's impact on students' health-related QoL. Significant differences were noted in the frequency of attendance of the online sessions and the PF, BP, PC, VT, DF, MH, and MC scores, with those attending all the sessions having a higher score than those attending sometimes or never. Students attending online sessions that included theoretical and practical work had higher BP, GH, and MH scores and lower ER scores. Those reporting that online education provided them with sufficient information had significantly higher BP and RP scores and lower VT scores. Furthermore, significantly lower SF and ER scores were noted for those preferring online over in-person education.

Relation between the SF-36 scale scores and the online education variables (One Way ANOVA).

| Physical components | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PF | RP | BP | GH | PC | |

| How much time did you attend the online sessions? | |||||

| All of the time | 84.1 (23.6) | 72.7 (37.6) | 76.1 (26.9) | 56.0 (16.3) | 72.2 (20.5) |

| Sometimes | 83.9 (22.3) | 69.4 (33.7) | 65.1 (27.3) | 53.8 (11.8) | 68.0 (18.3) |

| Never | 71.4 (26.1) | 64.0 (33.1) | 57.8 (32.7) | 51.0 (15.0) | 61.1 (22.8) |

| F | 3.440* | 0.862 | 10.092*** | 1.916 | 4.676** |

| Did online education include theoretical and practical work? | |||||

| Yes | 83.7 (14.0) | 72.3 (28.1) | 75.4 (16.7) | 56.5 (15.8) | 71.9 (20.7) |

| No | 82.8 (13.0) | 69.7 (23.9) | 67.2 (18.9) | 53.4 (13.9) | 68.3 (19.4) |

| F | 0.170 | 0.513 | 8.659** | 4.339* | 3.415 |

| Do you feel that online education provides you with sufficient information? | |||||

| Yes | 87.8 (10.6) | 75.3 (22.2) | 70.7 (16.8) | 56.1 (14.8) | 72.5 (18.2) |

| No | 80.5 (14.2) | 68.5 (28.1) | 71.8 (18.8) | 54.3 (14.9) | 68.8 (21.1) |

| F | 8.922** | 3.322* | 0.133 | 1.446 | 3.169 |

| How do you rate your satisfaction with the online sessions? | |||||

| High Satisfaction | 82.2 (16.2) | 67.7 (23.9) | 68.3 (29.4) | 53.8 (17.2) | 68.0 (22.8) |

| Moderate Satisfaction | 83.5 (12.2) | 73.9 (19.2) | 73.2 (23.3) | 56.7 (13.2) | 71.8 (18.1) |

| Low Satisfaction | 83.4 (13.9) | 69.2 (22.0) | 70.5 (28.3) | 53.4 (15.7) | 69.2 (20.9) |

| F | 0.075 | 1.047 | 0.857 | 2.257 | 1.192 |

| Do you prefer online education or in-person education? | |||||

| Online Education | 85.1 (12.9) | 68.2 (29.4) | 68.3 (17.7) | 55.3 (18.0) | 69.2 (21.9) |

| In-person Education | 82.9 (13.6) | 71.6 (25.5) | 72.0 (18.1) | 54.9 (14.3) | 70.3 (19.7) |

| F | 0.443 | 0.454 | 0.871 | 0.039 | 0.157 |

| Mental components | |||||

| VT | SF | ER | MH | MC | |

| How much time did you attend the online sessions? | |||||

| All of the time | 53.1 (23.4) | 62.3 (29.4) | 61.3 (34.1) | 56.4 (22.3) | 58.3 (25.3) |

| Sometimes | 46.2 (18.7) | 50.2 (25.0) | 63.3 (33.8) | 52.4 (17.3) | 53.0 (21.2) |

| Never | 45.8 (22.5) | 53.5 (23.3) | 46.7 (30.8) | 44.2 (16.6) | 47.5 (20.2) |

| F | 4.754** | 8.572*** | 1.518 | 4.938** | 3.753* |

| Did online education include theoretical and practical work? | |||||

| Yes | 51.0 (23.3) | 58.5 (30.3) | 56.8 (34.8) | 56.8 (21.5) | 55.7 (25.5) |

| No | 49.9 (21.0) | 57.3 (25.9) | 65.5 (32.6) | 51.8 (19.5) | 56.1 (22.1) |

| F | 0.257 | 0.185 | 3.936* | 5.950* | 0.019 |

| Do you feel that online education provides you with sufficient information? | |||||

| Yes | 47.8 (19.1) | 54.7 (25.6) | 63.3 (34.0) | 53.4 (18.2) | 54.8 (21.5) |

| No | 52.0 (23.7) | 59.8 (29.5) | 59.7 (33.9) | 54.9 (22.1) | 56.6 (25.2) |

| F | 3.359* | 2.981 | 0.648 | 0.557 | 0.523 |

| How do you rate your satisfaction with the online sessions? | |||||

| High Satisfaction | 48.9 (21.1) | 51.4 (30.5) | 54.9 (34.3) | 52.1 (21.3) | 51.8 (24.6) |

| Moderate Satisfaction | 50.8 (20.7) | 60.5 (25.2) | 61.1 (33.2) | 55.5 (19.0) | 57.0 (21.8) |

| Low Satisfaction | 50.7 (24.3) | 57.5 (30.2) | 63.4 (34.6) | 53.9 (22.4) | 56.4 (25.9) |

| F | 0.184 | 2.534 | 0.872 | 0.715 | 1.174 |

| Do you prefer online education or in-person education? | |||||

| Online Education | 47.3 (20.2) | 51.9 (28.9) | 48.1 (36.3) | 50.7 (20.4) | 49.5 (23.1) |

| In-person Education | 51.0 (22.5) | 59.0 (27.9) | 63.4 (33.1) | 55.1 (20.7) | 57.1 (23.9) |

| F | 1.509 | 3.308* | 6.502* | 2.400 | 5.426* |

*p < 0.050; **p < 0.010; ***p < 0.001. F = F statistics.

PF: Physical Functioning, RP: Role Physical role, BP: Bodily Pain, GH: General Health, PC: total Physical component, VT: Vitality, SF: Social Functioning, ER: Emotional Role MH: Mental Health and MC: total Mental Component.

After adjusting for covariates, it was found that the students reported satisfaction had no influence on the SF-36 scores, and the preferences of students (online or in-person education) did not influence any of the physical components scores. Students attending some of the sessions had significantly lower BP (b = –5.0), PC (b = –2.1), VT (b = –3.4), SF (b = –6.3), and MC (b = –2.8) scores compared to those attending all the sessions, while those never attending the sessions had lower PF (b = –3.7), BP (b = –5.6), PC (b = –3.7), MH (b = –3.7) and MC (b = –3.6) scores. The BP (b = –6.1), GH (b = –3.1), and MH (b = –4.1) scores decreased if the online sessions did not include both practical and theoretical work. Students reporting that online education cannot provide sufficient information had significantly lower PF (b = –6.5) and RP (b = –6.8) scores but a greater VT score (b = 4.4). Finally, those preferring in-person over online education had significantly higher SF (b = 8.0), ER (b = 14.3), and MC (b = 8.0) scores (Table 4).

Predictors of the SF-36 scale scores: Multivariate analysis results (Linear regression model).

| Physical components | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFB [95% CI] | RPB [95% CI] | BPB [95% CI] | GHB [95% CI] | PCB [95% CI] | |

| Intercept | 94.6[86.4 – 102.9] | 82.1[69.7 – 94.5] | 84.8[76.3 – 93.2] | 59.6[54.9 – 64.1] | 72.2[69.7 – 74.7] |

| How much time did you attend the online sessions? | |||||

| (Sometimes Vs All of the time) | –0.3[–2.7 – 2.2] | –5.0***[–7.9 – –2.0] | –2.1*[–4.2 – –0.1] | ||

| (Never Vs All of the time) | –3.7*[–6.9 – –0.5] | –5.6**[–9.3 – –1.8] | –3.7**[–6.5 – –1.0] | ||

| Did online education include theoretical and practical work? | |||||

| (No Vs Yes) | –6.1*[–11.6 – –0.7] | –*3.1[–6.0 – –0.2] | |||

| Do you feel that online education provides you with sufficient information? | |||||

| (No Vs Yes) | –6.5**[–11.2 – –1.7] | –6.8*[–14.1 – –0.1] | |||

| R square (%) | 34% | 8% | 60% | 11% | 23% |

| Mental components | |||||

| VTB [95% CI] | SFB [95% CI] | ERB [95% CI] | MHB [95% CI] | MCB [95% CI] | |

| Intercept | 39.3[38.2 – 53.8] | 47.7[33.7 – 61.8] | 23.2[–1.4 – 47.7] | 62.2[55.9 – 68.5] | 43.6[31.6 – 55.6] |

| How much time did you attend the online sessions? | |||||

| (Sometimes Vs All of the time) | –3.4**[–5.7 – –1.0] | –6.3***[–9.3 – –3.4] | –1.7[–3.9 – 0.5] | –2.8*[–5.3 – –0.3] | |

| (Never Vs All of the time) | –2.8[–5.8 – 0.2] | –3.0[–6.8 – 0.8] | –3.7**[–6.5 – –0.9] | –3.6*[–6.8 – –0.4] | |

| Did online education include theoretical and practical work? | |||||

| (No Vs Yes) | 7.7[–0.8 – 16.3] | –4.1*[–8.1 – –0.1] | |||

| Do you feel that online education provides you with sufficient information? | |||||

| (No Vs Yes) | 4.4*[0.1 – 8.9] | ||||

| Do you prefer online education or in-person education? | |||||

| (In-person Vs Online) | 8.0*[0.6 – 15.5] | 14.3*[2.5 – 26.1] | 8.0*[1.7 – 14.4] | ||

| R square (%) | 32% | 52% | 24% | 34% | 33% |

Results are presented as B [95% confidence interval (CI)]. *p < 0.050; **p < 0.010; ***p < 0.001.

PF: Physical Functioning, RP: Role Physical role, BP: Bodily Pain, GH: General Health, PC: total Physical component, VT: Vitality, SF: Social Functioning, ER: Emotional Role MH: Mental Health and MC: total Mental Component.

The present study aimed to investigate the impact of online education on the health-related QoL of medical students in Lebanon. Similarly to our findings, a recent study found low QoL among university students during the COVID-19 pandemic, mainly the mental components of the SF-36.19 In contrast, compared to a previous study conducted in Lebanon, the QoL of students was adversely affected,21 which could be possibly associated with online education and other stressors during the data collection period, such as political unrest, economic crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic. Most students attended all the online sessions, and around 32% attended some of them. Students showed low and moderate satisfaction with the online education sessions, and about 37% reported that these programs needed to provide them with sufficient information compared to in-person education. Similarly to other studies, students’ satisfaction was moderate, possibly due to their unfamiliarity with the different online platforms.22 A literature review published in 2021 revealed that accessibility problems, technical issues, mental health, and lecturer commitment could affect students’ satisfaction and adaptation to online education.23 Most students in this study preferred in-person over online education, likely associated with the fact that the perceived learning outcomes are influenced by the impact of the interactions in classrooms, course structure, and students’ motivation.24 Based on the SF-36 health survey, students had high physical and relatively low mental component scores. Although the online modality was reported to be time-saving, limitations such as content perception and technical and behavioral challenges during the sessions and the exams were also reported among students.25 Research showed that medical students experienced poor sleep quality and depression during the pandemic independently of their education level.26 Students attending some or none of the sessions had significantly lower BP scores than those attending all of them, possibly associated with physical and neck pain due to prolonged positioning when using the devices.27 Lower BP and GH scores were reported among students attending sessions that included only theoretical work. This finding can be explained by higher academic achievement among students translating their theoretical knowledge into practice.28 Medical students reporting that online education did not provide sufficient information had significantly lower PF and RP scores which can be related to the low student-to-instructor and student-to-student interactions through the online mode.29 Lower VT and SF scores were reported among those attending some sessions compared to those attending all the sessions. This can be associated with detachment from colleagues, affecting students' motivation, QoL, and vitality.30 It can also explain the higher SF and ER scores among those preferring in-person education.

This study has limitations. Selection bias may have been induced since the data collectors randomly selected students, and possibly only motivated ones were willing to participate. However, pharmacists were uniformly trained and used the same data collection form, and a different researcher performed data coding and analysis. Recall bias may have also arisen since data collection was performed at the end of the academic year. The study sample was relatively small, which might not allow the extrapolation of the findings to all medical students. Nonetheless, the present study is the first one performed in both public and private universities to tackle the impact of online education on the health-related QoL of medical students using a validated questionnaire. It is suggested that other variables, such as employment status and availability of technical support and resources, will be addressed in future studies.

The COVID-19 pandemic directly impacted the QoL of medical students, namely their mental health. Online teaching imposed new challenges, with most students reporting moderate or low satisfaction. Those attending the sessions more frequently and those reporting that online education provided sufficient information had significantly higher scores. Medical students in Lebanon had a higher preference for in-person education, possibly due to its novelty and to other technological, technical, or personal challenges. Future research exploring the reasons and viable solutions should be performed to maintain a steady level of education during unanticipated situations.