Medicine is inserted in a context in which the quality of healthcare is linked directly with the number of exams and procedures, giving attention to erroneous thoughts of values from the overuse of exams and procedures, consequently; creating an overload on the health system. One of the greatest challenges regarding the cost of medical care is to understand to solve low-quality care rates and impending health management deficits, there needs to be an awareness of professionals about excessive medical care that does not contribute to the health of the population. This study seeks to know if students, residents, and physicians know about the costs of the main medical clinic exams.

Material and methodsEmpirical cross-sectional study, involving students attending the medical internship, professors of the medical internship, and residents.

ResultsOf the 263 participants, 66.9% were students, 19.4% were teachers, and 13.7% were residents. It is observed, in this study, most of the participants did not know the values of tests frequently used in medical practice, such as blood count and blood glucose, as well as imaging tests such as chest radiography, ultrasound of the total abdomen, and cranial tomography. There was greater knowledge of exam values among teachers.

ConclusionStudents, residents, and physicians demonstrated they were unaware of the cost of the main exams in medical practice. A study like this can improve reflective behavior regarding to the cost-conscious attitude among medical students and doctors.

La medicina se inserta en un contexto en el que la calidad de la atención en salud se vincula directamente con la cantidad de exámenes y procedimientos, prestándose atención a pensamientos erróneos de valores a partir del uso excesivo de exámenes y procedimientos, en consecuencia; creando una sobrecarga en el sistema de salud. Uno de los mayores desafíos en relación con el costo de la atención médica es comprender que para solucionar los índices de baja calidad de la atención y los déficits inminentes en la gestión de la salud, es necesario que haya una conciencia de los profesionales sobre la atención médica excesiva que no contribuye a la salud de la población. Este estudio busca conocer si estudiantes, residentes y médicos conocen los costos de los principales exámenes clínicos médicos.

Materiais y Métodosestudio empírico transversal, involucrando estudiantes asistentes al internado médico, profesores del internado médico y residentes.

ResultadosDe los 263 participantes, el 66,9% eran estudiantes, el 19,4% eran docentes y el 13,7% eran residentes. Se observa, en este estudio, que la mayoría de los participantes desconocían los valores de pruebas frecuentemente utilizadas en la práctica médica, como hemograma y glucemia, así como pruebas de imagen como radiografía de tórax, ecografía de abdomen total. y tomografía craneal. Hubo un mayor conocimiento de los valores de los exámenes entre los docentes.

ConclusiónEstudiantes, residentes y médicos demostraron desconocer el costo de los principales exámenes en la práctica médica. Un estudio como este puede mejorar el comportamiento reflexivo sobre la actitud consciente de los costos entre los estudiantes de medicina y los médicos.

The 20th century was marked, in the health sciences, by the advent of the Technical–Scientific–Informational Revolution. Thus, its progress took great strides and, since then, a reconfiguration of disease prevention and cure has begun due to the rise of new technologies. However, the “medicine of the future” is inserted within a context in which the quality of healthcare is associated with the exuberance of exams and procedures performed, giving rise to erroneous thinking that values the overuse of exams and procedures, which can result in psychological, physical, and financial damage to the health of the individual.1

This overuse may be accompanied by the absence of clear scientific evidence on the effectiveness of its use, generating a surplus demand on health resources.2 In this scenario, the excessive indication of tests is still particularized in overdiagnosis, when diagnoses are made of conditions that will not cause symptoms, but can generate damage throughout the patient's life, inappropriately labeling people as having chronic diseases and may also result in overtreatment, that is, exposing these patients to treatments without any benefit to the individual's health. Therefore, the excess of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures exposes the patient to behaviors that are little effective or ineffective, in addition to allowing substantial damage and expenses to health services.3

One of the great challenges regarding the cost of healthcare is to understand that to solve the high rates of poor quality care and imminent deficits in health management, there needs to be an awareness of professionals about excessive healthcare that does not contribute to the health of the population.4 Added to this, the constant evolution of science, especially technological advances, leads health professionals to seek constant updating, which may result in inadequate application of these diagnostic and treatment resources. However, physicians do not always have these most current efficacy data and, despite acting with the best intentions, they can recommend interventions that are no longer considered necessary, especially due to the pressure of the patient who has a mistaken “more is better” culture. Because of this, patients need reliable information to help them understand that more care is not always better and, in some cases, may, in addition to not generating benefit, result in harm to their health, as well as overloading the public or private management system.4

It is in this scenario that the Choosing Wisely (CW) campaign arises, whose strategy is based on the creation of specific lists for each specialty, based on the identification of frequent tests or procedures of questioned efficacy due to the low value for patients. This campaign began in 2012 in the United States and, since then, has been expanding worldwide, and is currently present in about 20 countries. The main objective of this initiative is not to save resources but to improve the quality of individual care through the reflective awareness of health professionals and patients about the correct use and the appropriate time to request diagnostic tests and interventions, avoiding unnecessary and potentially iatrogenic procedures.5

It is foreseen in the original CW campaign the implementation in the graduation of the medical course, but it is still little applied in medical schools. Thus, many physicians are trained without the knowledge, or even interest, of where and how to inform themselves about the costs of exams in medical practice, as well as the impacts of their overuse on the health system and on the patient's life.6 In this context, this study seeks to know if students, residents, and physicians know about the costs of the main medical clinic exams.

MethodThis is an empirical study of a quantitative nature and cross-sectional between August 2020 and November 2020. Students attending the medical internship, which corresponds to the 9th, 10th, 11th, and 12th semesters of the course; professors of the medical internship and residents were invited to participate in the study. This is a non-probabilistic sample by accessibility. Acting students, students duly enrolled in the medical internship in 2020 and residents who agreed to participate in the research by signing the Informed Consent Form were included. Participants who did not answer 80% or more of the questions contained in the research questionnaire were excluded.

The participants online through the SurveyMonkey® platform, answered a questionnaire containing identification data and questions that address the knowledge about exam costs in the medical clinic area (answered using a 4-point Likert scale: 4 – strongly agree, 3 – moderately agree, 2 – moderately disagree, and 1 – strongly disagree.

Initially, descriptive analyses (mean, standard deviation, and frequency distribution) were performed to characterize the participants in occupational and personal terms, as well as in relation to the central variables of the study. Then, inferential statistical analyses were performed to assess the knowledge of medical students, residents, and professors about the costs of exams in a medical clinic. For the comparative analyses between the groups, the chi-square test was used, depending on the distribution of the data in terms of normality. Values of p<.05 were considered significant.

ResultsThe number of participants was 263, with 176 (66.9%) students; 51 (19.4%) teachers and 36 (13.7%) residents, predominantly female (63.9%) (Table 1).

Characterization of participants on the knowledge of medical students, residents, and professors about the costs of exams in a medical clinic. 2020 (N=263).

| Mean [SD] or N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age | 29 (±10.3) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 168 (63.9) |

| Male | 95 (36.1) |

| Student | 176 (66.9) |

| Resident | 36 (13.7) |

| Professor | 51 (19.4) |

| Semester (if student) | |

| 9th | 38 (21.5) |

| 10th | 38 (21.5) |

| 11th | 39 (22.0) |

| 12th | 62 (35.0) |

| Degree (if professor) | |

| Residence | 13 (25.5) |

| Master's degree | 21 (41.2) |

| PhD | 17 (33.3) |

Source: Author data.

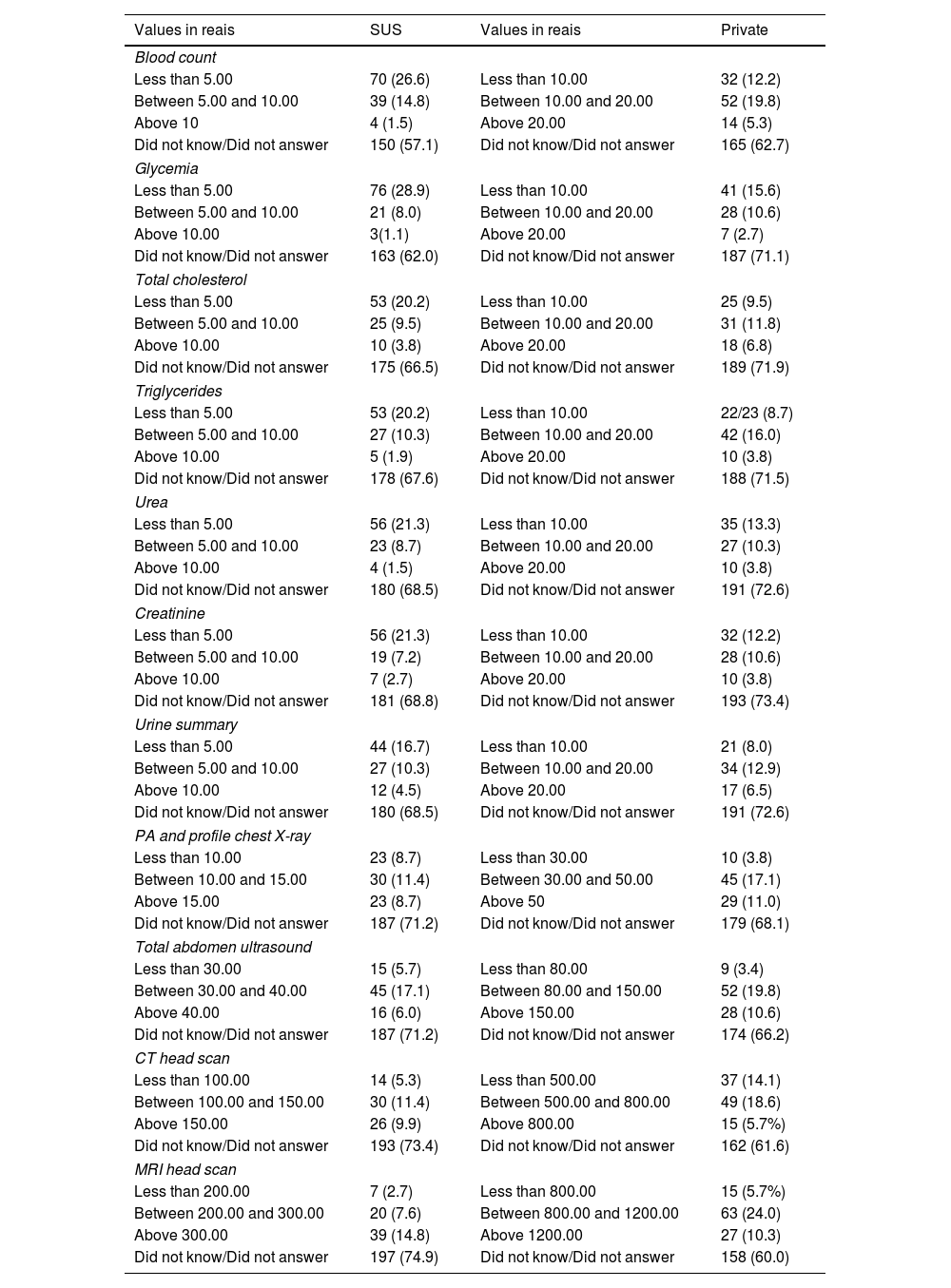

When analyzing the knowledge of students, residents, and medical professors about the value of the exams, it is observed that most participants did not know the values of exams frequently used in medical practice in SUS (Unified Health System), such as: blood count (57.1%) and blood glucose (62%), as well as imaging exams: chest radiography (71.1%), total abdomen ultrasound (71.1%), and skull tomography (73.4%) (Table 2).

Knowledge of medical students, residents, and professors about the costs of exams in a medical clinic. 2020 (N=263).

| Values in reais | SUS | Values in reais | Private |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood count | |||

| Less than 5.00 | 70 (26.6) | Less than 10.00 | 32 (12.2) |

| Between 5.00 and 10.00 | 39 (14.8) | Between 10.00 and 20.00 | 52 (19.8) |

| Above 10 | 4 (1.5) | Above 20.00 | 14 (5.3) |

| Did not know/Did not answer | 150 (57.1) | Did not know/Did not answer | 165 (62.7) |

| Glycemia | |||

| Less than 5.00 | 76 (28.9) | Less than 10.00 | 41 (15.6) |

| Between 5.00 and 10.00 | 21 (8.0) | Between 10.00 and 20.00 | 28 (10.6) |

| Above 10.00 | 3(1.1) | Above 20.00 | 7 (2.7) |

| Did not know/Did not answer | 163 (62.0) | Did not know/Did not answer | 187 (71.1) |

| Total cholesterol | |||

| Less than 5.00 | 53 (20.2) | Less than 10.00 | 25 (9.5) |

| Between 5.00 and 10.00 | 25 (9.5) | Between 10.00 and 20.00 | 31 (11.8) |

| Above 10.00 | 10 (3.8) | Above 20.00 | 18 (6.8) |

| Did not know/Did not answer | 175 (66.5) | Did not know/Did not answer | 189 (71.9) |

| Triglycerides | |||

| Less than 5.00 | 53 (20.2) | Less than 10.00 | 22/23 (8.7) |

| Between 5.00 and 10.00 | 27 (10.3) | Between 10.00 and 20.00 | 42 (16.0) |

| Above 10.00 | 5 (1.9) | Above 20.00 | 10 (3.8) |

| Did not know/Did not answer | 178 (67.6) | Did not know/Did not answer | 188 (71.5) |

| Urea | |||

| Less than 5.00 | 56 (21.3) | Less than 10.00 | 35 (13.3) |

| Between 5.00 and 10.00 | 23 (8.7) | Between 10.00 and 20.00 | 27 (10.3) |

| Above 10.00 | 4 (1.5) | Above 20.00 | 10 (3.8) |

| Did not know/Did not answer | 180 (68.5) | Did not know/Did not answer | 191 (72.6) |

| Creatinine | |||

| Less than 5.00 | 56 (21.3) | Less than 10.00 | 32 (12.2) |

| Between 5.00 and 10.00 | 19 (7.2) | Between 10.00 and 20.00 | 28 (10.6) |

| Above 10.00 | 7 (2.7) | Above 20.00 | 10 (3.8) |

| Did not know/Did not answer | 181 (68.8) | Did not know/Did not answer | 193 (73.4) |

| Urine summary | |||

| Less than 5.00 | 44 (16.7) | Less than 10.00 | 21 (8.0) |

| Between 5.00 and 10.00 | 27 (10.3) | Between 10.00 and 20.00 | 34 (12.9) |

| Above 10.00 | 12 (4.5) | Above 20.00 | 17 (6.5) |

| Did not know/Did not answer | 180 (68.5) | Did not know/Did not answer | 191 (72.6) |

| PA and profile chest X-ray | |||

| Less than 10.00 | 23 (8.7) | Less than 30.00 | 10 (3.8) |

| Between 10.00 and 15.00 | 30 (11.4) | Between 30.00 and 50.00 | 45 (17.1) |

| Above 15.00 | 23 (8.7) | Above 50 | 29 (11.0) |

| Did not know/Did not answer | 187 (71.2) | Did not know/Did not answer | 179 (68.1) |

| Total abdomen ultrasound | |||

| Less than 30.00 | 15 (5.7) | Less than 80.00 | 9 (3.4) |

| Between 30.00 and 40.00 | 45 (17.1) | Between 80.00 and 150.00 | 52 (19.8) |

| Above 40.00 | 16 (6.0) | Above 150.00 | 28 (10.6) |

| Did not know/Did not answer | 187 (71.2) | Did not know/Did not answer | 174 (66.2) |

| CT head scan | |||

| Less than 100.00 | 14 (5.3) | Less than 500.00 | 37 (14.1) |

| Between 100.00 and 150.00 | 30 (11.4) | Between 500.00 and 800.00 | 49 (18.6) |

| Above 150.00 | 26 (9.9) | Above 800.00 | 15 (5.7%) |

| Did not know/Did not answer | 193 (73.4) | Did not know/Did not answer | 162 (61.6) |

| MRI head scan | |||

| Less than 200.00 | 7 (2.7) | Less than 800.00 | 15 (5.7%) |

| Between 200.00 and 300.00 | 20 (7.6) | Between 800.00 and 1200.00 | 63 (24.0) |

| Above 300.00 | 39 (14.8) | Above 1200.00 | 27 (10.3) |

| Did not know/Did not answer | 197 (74.9) | Did not know/Did not answer | 158 (60.0) |

Source: Author data.

Correct expected values are highlighted in bold; SUS: Unified Health System (Brazilian public health system); Private=when amount is paid by the patient himself; 1 dollar corresponds to 5.48 reais.

When comparing the knowledge of students, residents, and medical professors about the costs of the exams, it is observed that the professors had a greater knowledge compared to students and residents, with a statistically significant p in most exams, although all 3 groups had a percentage of correct answers below 50% (Table 3).

Comparison of the knowledge of medical students, residents, and professors about the costs of exams in a medical clinic. 2020 (N=263).

| Students | Residents | Professors | pa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=177) | (N=36) | (N=50) | ||

| % Hit | % Hit | % Hit | ||

| SUS blood count | 20.9 | 30.6 | 44.0 | .004 |

| Private blood count | 12.4 | 36.1 | 34.0 | .001 |

| SUS blood glucose | 23.7 | 33.3 | 44.0 | .017 |

| Private blood glucose | 5.1 | 8.3 | 32.0 | .001 |

| SUS total cholesterol | 16.9 | 22.2 | 30.0 | .120 |

| Private total cholesterol | 7.9 | 13.9 | 24.0 | .007 |

| SUS triglycerides | 16.4 | 22.2 | 32.0 | .049 |

| Private triglycerides | 11.3 | 13.9 | 34.0 | .001 |

| SUS urea | 17.5 | 22.2 | 34.0 | .042 |

| Private urea | 6.2 | 13.9 | 22.0 | .004 |

| SUS creatinine | 16.4 | 25.0 | 36.0 | .010 |

| Private creatinine | 7.3 | 13.9 | 20.0 | .030 |

| SUS urine summary | 10.2 | 16.7 | 40.0 | .001 |

| Private urine summary | 7.3 | 16.7 | 30.0 | .001 |

| SUS chest X-ray | 5.1 | 11.1 | 20.0 | .004 |

| Private chest X-ray | 9.0 | 11.1 | 18.0 | .203 |

| SUS USG total abdomen | 12.4 | 16.7 | 34.0 | .002 |

| Private USG total abdomen | 14.1 | 25.0 | 36.0 | .002 |

| SUS head CT scan | 3.4 | 8.3 | 10.0 | .127 |

| Private head CT scan | 7.3 | 11.1 | 22.0 | .012 |

| SUS head MRI scan | 5.1 | 2.8 | 20.0 | .001 |

| Private head MRI scan | 9.0 | 11.1 | 14.0 | .585 |

SUS: Unified Health System; USG: Ultrasonography; CT: Tomography; MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging.

Source: Author data.

The adoption of cost-conscious conducts in medical practice is able to reduce the exaggerated request for procedures and exams, promoting, in addition to a good patient experience, an improvement in the quality of services.6,7 In the present study, a questionnaire was created to assess the knowledge of students, residents, and medical professors about the cost of exams in the medical clinic, which was applied to a sample of 263 participants, of whom 176 were students, 57% of them from the last year of the course; 36 were residents and 51 were professors. The profile of this sample allowed an analysis of the knowledge of the cost of exams in a longitudinal way: at an important moment of graduation, the internship, and at 2 other relevant moments, the residence and the activity of physicians as teachers.

The results showed, in general, the lack of knowledge of both students, residents, and teachers about the costs of the exams, revealing that although 98.8% of the interviewees think it is important for the physician to know the cost of exams and 53.1% state that they address this topic when talking to the patient, only 19.7% know some source of price search. This shows that although physicians consider price an important factor in decisions at the time of request, they have difficulty estimating costs accurately or finding pricing information.8

Two previous studies have demonstrated this lack of knowledge by physicians about the costs of medications prescribed to patients, so that although they know where to find this information, they verify these values very little, concluding that cost awareness has not improved in the last 25 years.9,10 However, although the present study also addresses cost-consciousness in medical practice, it brings an approach focused on the cost of exams requested by physicians, which is a reflection still little addressed, despite directly interfering with health management.

When asked about the values of the exams, more than half of the interviewees answered that they did not know how to refer the real cost even of those who frequently request it in medical practice, and a greater ignorance of the costs of the imaging exams was observed when compared to the laboratory ones. It was also observed that among the laboratory tests, there was a greater lack of knowledge of the values in the private network than in the SUS. Among the imaging exams, the reverse occurred: there was a greater lack of knowledge of costs in the SUS, when compared to the private network.

It was also observed that only about 32.7% of the interviewees answered the values of the tests requested in the SUS with a mean of only 18% of correct answers. When asked about the values in the private service, about 31.6% of the total interviewees said they knew such costs; however, there was a mean of correct answers of only 11.9%. In both scenarios, there was a higher mean accuracy in laboratory test values than in imaging. This becomes a major problem since it is these same physicians who play a central role in health spending, as they are responsible for the “purchases” of tests and therapies on behalf of patients.8

One strategy to make the medical request cost-conscious is to increase the transparency of cost data for requesting health professionals, since with this knowledge there may be a change of requests to lower cost alternatives, but of the same value, or even a waiver of requests. The display of prices together with the initial request by the physician to the supplier is a way to raise awareness to achieve this goal.8,11

Students, residents, and physicians did not correctly estimate exam costs. However, it is important to consider that its general cost estimates improved with the increase in medical experience and consolidation of the knowledge acquired with the practice. That is, the teaching physicians had a lower error rate than the other 2 groups. This difference was statistically significant for the estimation of the cost of all exams, except for the values of total cholesterol exams by SUS, chest radiography in the private service, CT of the head by SUS and MRI of the head in the private service.

From this, it is possible to assume that the rational use of health resources has been attracting more and more attention from physicians throughout their clinical practice. Since, although medicine is traditionally taught with a patient care approach that uses resources as if they were unlimited, after graduation, at some level of their medical practice, the conflict between traditional medical education and that which teaches the use of resources wisely leads the physicians to question the real need to request exams.12

Despite this, studies have shown that in the teaching of medicine, instructions about the cost-consciousness of care are traditionally not given, even if in the position of professionals – with a sophisticated understanding of the implications of excessive consumption of resources on health – it is an obligation to consider the costs.12,13 This is also demonstrated in this study where more than 50% of teaching physicians still lack knowledge about the costs of medical care. This fact is reflected in the knowledge of medical students and resident physicians, of whom more than 70% were unaware of the values of these exams. This shows that students and residents have had little opportunity to practice and discuss diagnostic strategies based on cost–benefit.14

Knowing health costs is important when thinking about cost-conscious care. Since, understanding the behavior of physicians at the time of requesting the exams, it may be able to stimulate new management proposals to improve the quality of care and the rationalization of the use of resources in the health area.15,16 To this end, it is necessary to educate students since graduation about these costs, which is a responsibility of medical schools, since they have a moral commitment and the obligation to promote the opportunity of these students to develop conscious strategies in healthcare.14 In short, these data reinforce the need for health costs to be addressed in medical schools, since the false sense of knowledge has important consequences for clinical and educational practice.9,17

Students, residents, and physicians were unaware of the cost of the main medical practice exams, although most found it important for physicians to be aware of these costs. When comparing students, residents, and medical professors, it is observed that the professors had a greater knowledge about the costs of the exams. A greater lack of knowledge of the costs of imaging tests was observed when compared to the costs of laboratory tests. It was also observed that among the laboratory tests, there was a greater lack of knowledge of the values of the tests in the private network than in the SUS.

FundingThe authors declare that no funding was received for this article.

Ethics Committee ApprovalCAAE: 35011520.6.0000.5544.

Protocol number: 4.301.512.