The rational use of health resources has awakened us to the importance of including this theme in the curriculum of medical schools. This research aims to compare the perception of cost-conscious attitudes of medical students before and after the implementation of the CW campaign and after 1 year of medical practice.

Material and methodsLongitudinal study conducted with students and physicians, who answered a questionnaire on cost-conscious perception at 3 moments: before the implementation of the CW campaign during the undergraduate phase; immediately after the campaign; and after 1 year of medical practice. In order to make the comparison among the different moments, the T-test for paired samples was used.

ResultsIn the first 2 moments, 98 students participated, of which 80 also participated in the third moment, already as physicians. Most students disagreed that physicians should not think about cost when making therapeutic decisions, with a change after the educational actions (P = .001). There was agreement by the students on the items that refer to the physicians’ posture regarding science and responsibility to contain costs and discuss treatment options with patients. Comparing the answers after the campaign and at 1 year of practice, it was observed that the perception of cost-conscious attitudes was maintained.

ConclusionsStudents showed high perception of cost-consciousness, even before the implementation of the campaign. Nevertheless, after the educational actions, an increase in this perception was observed; and, after 1 year of medical practice, this perception was maintained.

el uso racional de los recursos de salud nos ha despertado la importancia de incluir este tema en el currículo de las facultades de Medicina. Esta pesquisa pretende comparar la percepción de las actitudes conscientes de los costos de los estudiantes de Medicina antes y después de la implementación de la campaña CW y después de un año de práctica médica.

Materiales y métodosestudio longitudinal realizado con estudiantes y médicos, quienes respondieron un cuestionario de percepción de conciencia de los costos en 3 momentos: antes de la implementación de la campaña CW durante la etapa de pregrado, inmediatamente después de la campaña y después de un año de práctica médica. Para realizar la comparación entre los diferentes momentos se utilizó la prueba T para muestras apareadas.

Resultadosen los 2 primeros momentos participaron 98 estudiantes, de los cuales 80 también participaron en el tercer momento, ya como médicos. La mayoría de los estudiantes no estuvo de acuerdo en que los médicos no deben pensar en el costo al tomar decisiones terapéuticas, con un cambio después de las acciones educativas (p = 0,001). Hubo acuerdo de los estudiantes en los ítems que se refieren a la postura de los médicos frente a la ciencia y la responsabilidad de contener costos y discutir opciones de tratamiento con los pacientes. Comparando las respuestas después de la campaña y al año de práctica, se observó que se mantuvo la percepción de actitudes conscientes de los costos.

Conclusioneslos estudiantes mostraron alta percepción de conciencia de los costos, incluso antes de la implementación de la campaña. Sin embargo, luego de las acciones educativas, se observó un aumento en esta percepción, y después de un año de práctica médica, esta percepción se mantuvo.

The management of resources and the growth of spending on health have acquired an important role for public policies in the world. In the United States (USA), these expenditures corresponded to 18% of the gross domestic product (GDP) in 2011, with a projection for 20% in 2020,1,2 while, in Brazil, in recent years, they have represented around 8%.3 It is estimated that 30% of this waste could be avoided, without harm to the patient, which is attributed, especially, to failures in service delivery, fraud, and overuse of procedures and treatments.2

In 2012, the Ministry of Health in Brazil, analyzing the number of diagnostic procedures in the Unified Health System (SUS, as per its Portuguese acronym) reported that the number of laboratory tests ranged from 0.7 to 2.1 tests per outpatient medical consultation;4 and, in 2015, a study conducted by the National Insurance School Foundation (FUNENSEG, as per its Portuguese acronym), showed that 40% of laboratory tests were unnecessary, corresponding to a waste of 10 billion reais.5

The discussion on medical professionalism was started in 2002, highlighting the following principles: priority of the patient’s well-being, autonomy of the individual, and social justice, in order to promote an adequate distribution of health care resources.6 Currently, with the advent of new procedures and new treatment techniques, it is observed a medical practice of overdiagnosis and, consequently, overtreatment, many times in an unnecessary way, not contributing to the health of the individual, which can generate harm and high costs to the health system.2,7

This practice of defensive medicine results in a culture in which the quality of care is directly related to the number of procedures carried out.7,8 However, physicians are aware of their defensive practice, as demonstrated by Panella et al.,9 in 2017, in a study in Italy, in which 59.8% reported practicing defensive medicine, with a predominance of the specialty of surgery (23.6%). One of the alternatives to improve this conscious management of health costs lies in medical education, in which students and physicians should be trained to acquire this behavior during their training.8,10

Based on this reflective thinking, the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) started the Choosing Wisely campaign in the USA, involving specialist societies to point out frequent medical practices that should not be adopted. The main goal of the campaign is to involve physicians and patients in order to improve the quality of care, which should be individualized, evidence-based, thus increasing the possibility of benefit and safety to the individual's health. Students are expected to participate in the campaign, encouraging them to reflect and question about the excess of tests and procedures.7,10

In Brazil, the Bahia School of Medicine and Public Health (EBMSP, as per its Portuguese acronym) was the pioneer in terms of implementing the CW campaign during the undergraduate phase, with the proposal to raise awareness among students and professors about unnecessary medical practices and cost-conscious attitudes.11 Although the implementation of this initiative represents, in itself, an important step to stimulate cost-consciousness, it is necessary to demonstrate evidence of its effectiveness. In light of the foregoing, this study is relevant and aims to compare the perception of cost-conscious attitudes of medical students before and after the implementation of the CW campaign and after 1 year of medical practice.

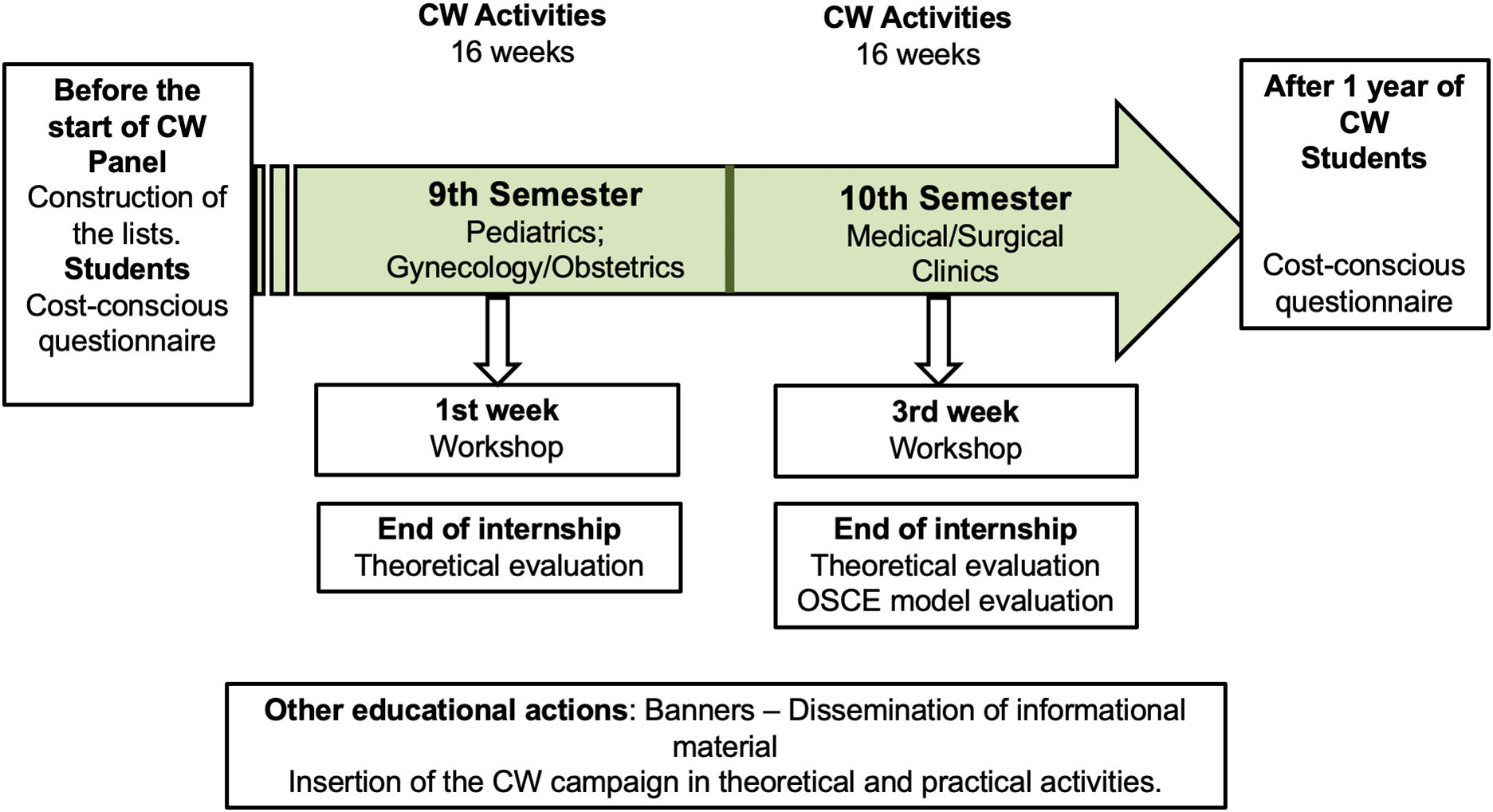

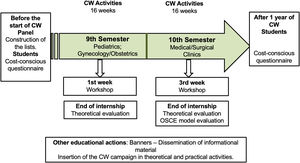

MethodsThe implementation of the CW campaign at EBMSP lasted 1 year and was composed of the following actions: (1) Construction of the list of recommendations of unnecessary conducts in the areas of pediatrics, gynecology/obstetrics, clinical medicine and surgery, which were used as a guide for the educational interventions. (2) Development of educational actions involving workshop lasting 1 h, using audiovisual resources and active learning methodology, in which the content, the aims of the CW campaign and the discussion of the recommendations of the lists were addressed; installation of banners in the internship fields containing the recommendations; dissemination of the campaign through the institution's communication channels and approach of the CW theme in theoretical and practical activities.

In order to evaluate the perception of cost-conscious attitudes, a reduced version of the scale originally proposed by Leep Hunderfund et al.13 and validated in Brazil by Gusmão et al.14 was used. The reduced version was composed of 8 items that included questions from important domains of medical practice, such as: costs of tests, treatments and interventions for society and the health system; cost-effectiveness of treatments; patient involvement in decisions and reflections on clinical practice. In order to answer it, a Likert scale12 of 4 points was adopted: “strongly agree”, “moderately agree”, “moderately disagree”, and “strongly disagree”. The reduced version did not impair the psychometric quality of the instrument, obtaining an internal consistency index of 0.75. In a complementary way, the following characterization questions were inserted in the questionnaire: age, gender, and previous knowledge of the CW campaign.

The participants were asked to answer the questionnaire at 3 different moments: before the start of the campaign implementation; immediately after the end of the campaign; and after 1 year of medical practice. The questionnaire was applied electronically (sent by e-mail), using the SurveyMonkey platform. The stages of this study are described in Fig. 1.

SPSS 23.0 software was used for data analysis. The results were described in frequency and percentage distribution tables, as well as by means and standard deviation. In order to compare the questionnaire answers before and after the campaign, the T-test for paired samples was used, and values of P<.05 were considered significant.

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of EBMSP, under number 1 627 477, and is in accordance with Resolution 466/2012 of the National Health Council and the Declaration of Helsinki. All volunteers signed an informed consent form.

ResultsThe expert panel for the construction of the CW campaign recommendation lists was composed of 42 professors: 8 from pediatrics; 11 from gynecology/obstetrics; 13 from clinical medicine; and 10 from surgery. Of the 102 enrolled students, 4 were excluded from the survey: 3 of them because they did not fill out the questionnaires completely, and 1 because he was a participant in the survey group. Therefore, 98 students answered the questionnaire before the CW campaign and immediately after its implementation. In the third application, the sample was composed of 80 physicians in direct patient care practice, now 1 year after training and sensitized for 2 years by the campaign. The mean age of the students was 23±1.9 years, with a predominance of females (64%). Of these, 36.6% reported prior knowledge of the CW campaign. The mean age of the participants regarding physicians was 26±2.1 years, with a predominance of females (70%).

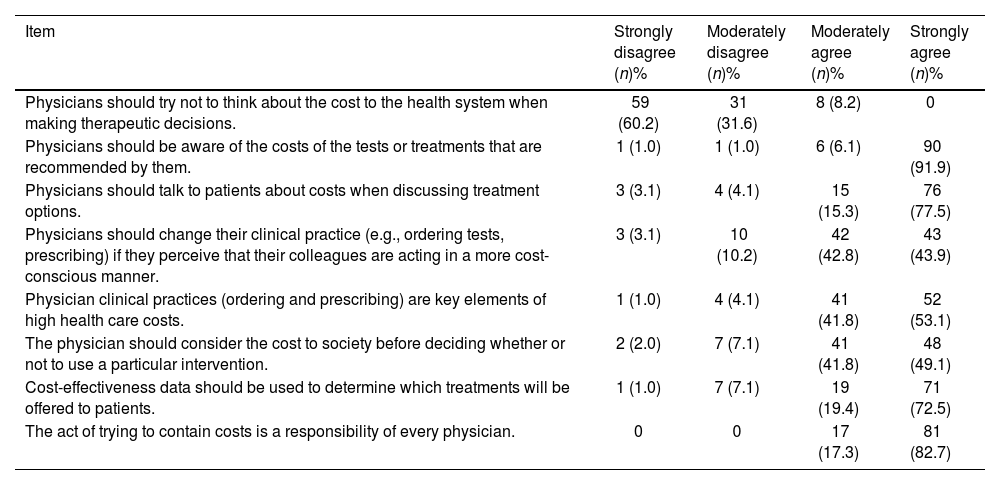

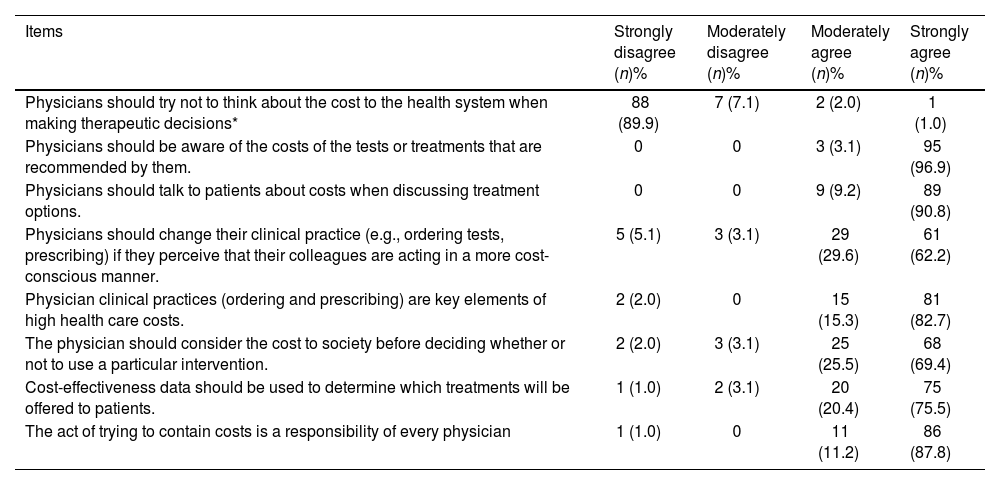

The questionnaire on the perception of cost-conscious attitudes was answered by all students participating in the survey, before and after the implementation of the CW campaign, and the results are described in Tables 1, 2, and 3.

Frequency of answers on perception of cost-conscious attitudes of medical internship students before the implementation of the Choosing Wisely campaign. Salvador, Bahia, 2018 (N = 98).

| Item | Strongly disagree (n)% | Moderately disagree (n)% | Moderately agree (n)% | Strongly agree (n)% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physicians should try not to think about the cost to the health system when making therapeutic decisions. | 59 (60.2) | 31 (31.6) | 8 (8.2) | 0 |

| Physicians should be aware of the costs of the tests or treatments that are recommended by them. | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) | 6 (6.1) | 90 (91.9) |

| Physicians should talk to patients about costs when discussing treatment options. | 3 (3.1) | 4 (4.1) | 15 (15.3) | 76 (77.5) |

| Physicians should change their clinical practice (e.g., ordering tests, prescribing) if they perceive that their colleagues are acting in a more cost-conscious manner. | 3 (3.1) | 10 (10.2) | 42 (42.8) | 43 (43.9) |

| Physician clinical practices (ordering and prescribing) are key elements of high health care costs. | 1 (1.0) | 4 (4.1) | 41 (41.8) | 52 (53.1) |

| The physician should consider the cost to society before deciding whether or not to use a particular intervention. | 2 (2.0) | 7 (7.1) | 41 (41.8) | 48 (49.1) |

| Cost-effectiveness data should be used to determine which treatments will be offered to patients. | 1 (1.0) | 7 (7.1) | 19 (19.4) | 71 (72.5) |

| The act of trying to contain costs is a responsibility of every physician. | 0 | 0 | 17 (17.3) | 81 (82.7) |

n: Number of medical students.

Source: Author’s database.

Frequency of answers on perception of cost-conscious attitudes of medical internship students after the implementation of the Choosing Wisely campaign. Salvador, Bahia, 2018 (N = 98).

| Items | Strongly disagree (n)% | Moderately disagree (n)% | Moderately agree (n)% | Strongly agree (n)% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physicians should try not to think about the cost to the health system when making therapeutic decisions* | 88 (89.9) | 7 (7.1) | 2 (2.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| Physicians should be aware of the costs of the tests or treatments that are recommended by them. | 0 | 0 | 3 (3.1) | 95 (96.9) |

| Physicians should talk to patients about costs when discussing treatment options. | 0 | 0 | 9 (9.2) | 89 (90.8) |

| Physicians should change their clinical practice (e.g., ordering tests, prescribing) if they perceive that their colleagues are acting in a more cost-conscious manner. | 5 (5.1) | 3 (3.1) | 29 (29.6) | 61 (62.2) |

| Physician clinical practices (ordering and prescribing) are key elements of high health care costs. | 2 (2.0) | 0 | 15 (15.3) | 81 (82.7) |

| The physician should consider the cost to society before deciding whether or not to use a particular intervention. | 2 (2.0) | 3 (3.1) | 25 (25.5) | 68 (69.4) |

| Cost-effectiveness data should be used to determine which treatments will be offered to patients. | 1 (1.0) | 2 (3.1) | 20 (20.4) | 75 (75.5) |

| The act of trying to contain costs is a responsibility of every physician | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 11 (11.2) | 86 (87.8) |

n: Number of medical students.

Source: Author’s database.

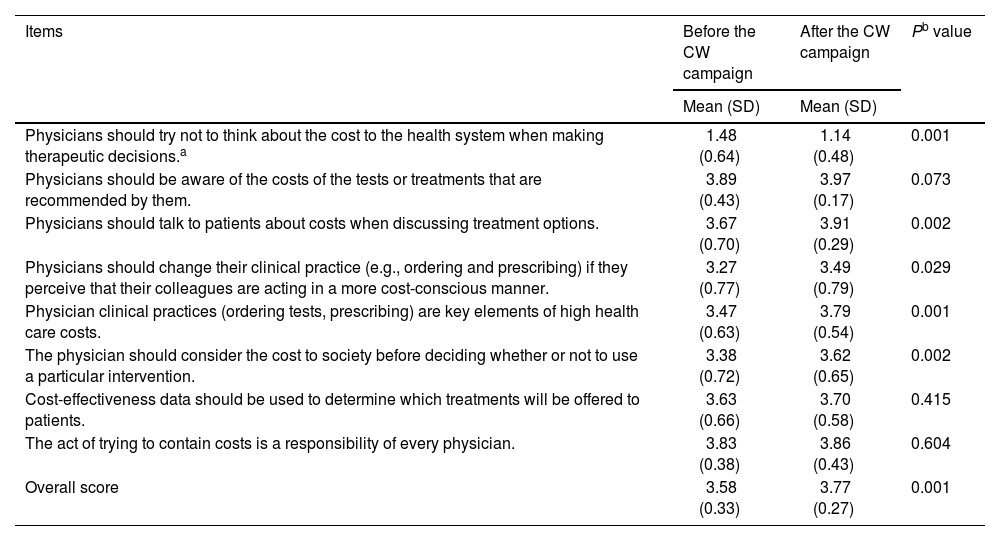

Comparison between the means of the answers on the perception of cost-conscious attitudes among medical internship students before and after the implementation of the Choosing Wisely campaign. Salvador, Bahia, 2018 (N = 98).

| Items | Before the CW campaign | After the CW campaign | Pb value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Physicians should try not to think about the cost to the health system when making therapeutic decisions.a | 1.48 (0.64) | 1.14 (0.48) | 0.001 |

| Physicians should be aware of the costs of the tests or treatments that are recommended by them. | 3.89 (0.43) | 3.97 (0.17) | 0.073 |

| Physicians should talk to patients about costs when discussing treatment options. | 3.67 (0.70) | 3.91 (0.29) | 0.002 |

| Physicians should change their clinical practice (e.g., ordering and prescribing) if they perceive that their colleagues are acting in a more cost-conscious manner. | 3.27 (0.77) | 3.49 (0.79) | 0.029 |

| Physician clinical practices (ordering tests, prescribing) are key elements of high health care costs. | 3.47 (0.63) | 3.79 (0.54) | 0.001 |

| The physician should consider the cost to society before deciding whether or not to use a particular intervention. | 3.38 (0.72) | 3.62 (0.65) | 0.002 |

| Cost-effectiveness data should be used to determine which treatments will be offered to patients. | 3.63 (0.66) | 3.70 (0.58) | 0.415 |

| The act of trying to contain costs is a responsibility of every physician. | 3.83 (0.38) | 3.86 (0.43) | 0.604 |

| Overall score | 3.58 (0.33) | 3.77 (0.27) | 0.001 |

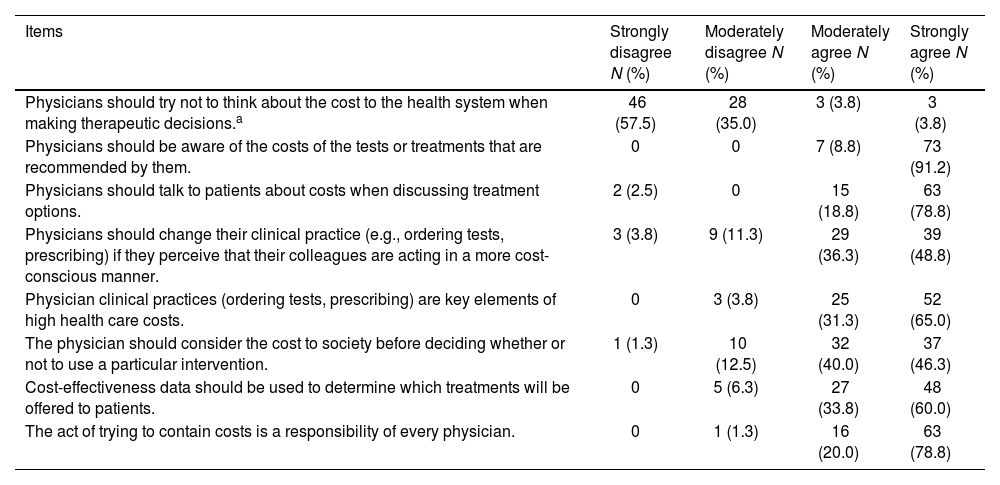

After 1 year of medical practice and 2 years of the campaign, most participants remain with their cost-conscious attitudes, highlighting that 100% agree that “Physicians should be aware of the costs of the tests or treatments that are recommended by them” (Table 4).

Frequency of answers on perception of cost-conscious attitudes of former medical internship students after 1 year of medical practice. Salvador, Bahia, 2020 (N = 80).

| Items | Strongly disagree N (%) | Moderately disagree N (%) | Moderately agree N (%) | Strongly agree N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physicians should try not to think about the cost to the health system when making therapeutic decisions.a | 46 (57.5) | 28 (35.0) | 3 (3.8) | 3 (3.8) |

| Physicians should be aware of the costs of the tests or treatments that are recommended by them. | 0 | 0 | 7 (8.8) | 73 (91.2) |

| Physicians should talk to patients about costs when discussing treatment options. | 2 (2.5) | 0 | 15 (18.8) | 63 (78.8) |

| Physicians should change their clinical practice (e.g., ordering tests, prescribing) if they perceive that their colleagues are acting in a more cost-conscious manner. | 3 (3.8) | 9 (11.3) | 29 (36.3) | 39 (48.8) |

| Physician clinical practices (ordering tests, prescribing) are key elements of high health care costs. | 0 | 3 (3.8) | 25 (31.3) | 52 (65.0) |

| The physician should consider the cost to society before deciding whether or not to use a particular intervention. | 1 (1.3) | 10 (12.5) | 32 (40.0) | 37 (46.3) |

| Cost-effectiveness data should be used to determine which treatments will be offered to patients. | 0 | 5 (6.3) | 27 (33.8) | 48 (60.0) |

| The act of trying to contain costs is a responsibility of every physician. | 0 | 1 (1.3) | 16 (20.0) | 63 (78.8) |

Source: author’s database.

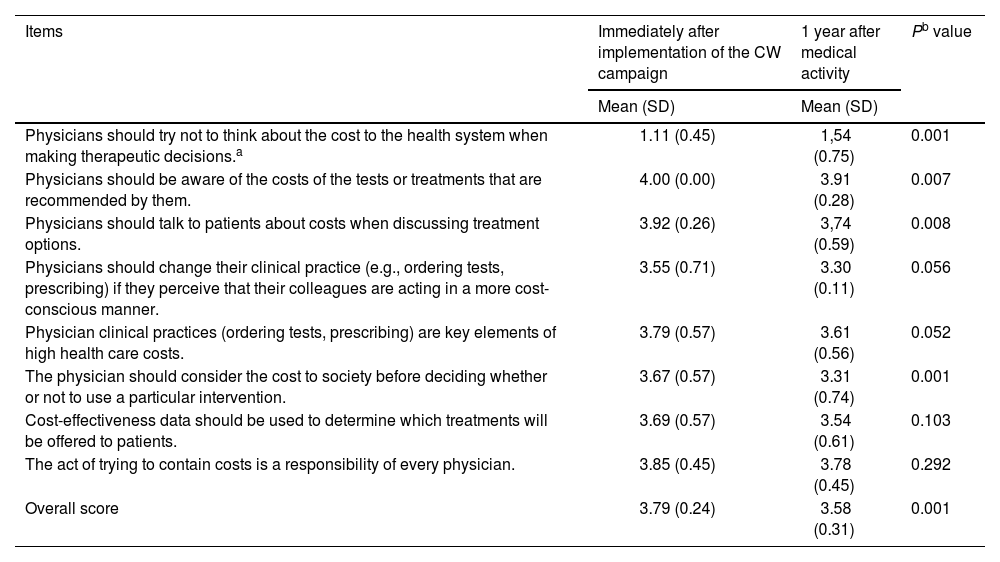

Nonetheless, when comparing the means of the answers on the perception of cost-conscious attitudes immediately after the implementation of the campaign and 1 year after the medical activity, it is observed that the overall score and most of the items point to a slight reduction in the reflective attitude about cost-consciousness (Table 5).

Comparison between the means of the answers on the perception of cost-conscious attitudes among medical internship students, immediately after implementation of the Choosing Wisely campaign and 1 year after medical activity. Salvador, Bahia, 2018 (N = 80).

| Items | Immediately after implementation of the CW campaign | 1 year after medical activity | Pb value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Physicians should try not to think about the cost to the health system when making therapeutic decisions.a | 1.11 (0.45) | 1,54 (0.75) | 0.001 |

| Physicians should be aware of the costs of the tests or treatments that are recommended by them. | 4.00 (0.00) | 3.91 (0.28) | 0.007 |

| Physicians should talk to patients about costs when discussing treatment options. | 3.92 (0.26) | 3,74 (0.59) | 0.008 |

| Physicians should change their clinical practice (e.g., ordering tests, prescribing) if they perceive that their colleagues are acting in a more cost-conscious manner. | 3.55 (0.71) | 3.30 (0.11) | 0.056 |

| Physician clinical practices (ordering tests, prescribing) are key elements of high health care costs. | 3.79 (0.57) | 3.61 (0.56) | 0.052 |

| The physician should consider the cost to society before deciding whether or not to use a particular intervention. | 3.67 (0.57) | 3.31 (0.74) | 0.001 |

| Cost-effectiveness data should be used to determine which treatments will be offered to patients. | 3.69 (0.57) | 3.54 (0.61) | 0.103 |

| The act of trying to contain costs is a responsibility of every physician. | 3.85 (0.45) | 3.78 (0.45) | 0.292 |

| Overall score | 3.79 (0.24) | 3.58 (0.31) | 0.001 |

Source: Author’s database.

The cost-conscious use of health resources is a challenge for managers and educators around the world, since an important portion of these costs are due to medical decisions, generating a cascade of decisions that are responsible for about 80% of health costs.15 Most physicians recognize the importance of acting in the most cost-conscious way, although their commitment to reducing costs is not observed in clinical practice.16

The implementation of educational actions in undergraduate medical education can change student behavior, since physicians form their habits during training and can still be influenced by a more reflective clinical practice. If there is no planned undergraduate education on cost-consciousness and patient-centered care, students may adopt any practices perceived in their professors.17 In 2015,18 a systematic review demonstrated that educating physicians about high-value cost-consciousness involves transmission of specific knowledge, reflective practice, and a supportive faculty and medical school environment.

In general, it was possible to demonstrate that students already had a good level of agreement with cost-conscious attitudes, even before the implementation of the campaign. This may be a reflection of the place they are still “sheltered” from the real demands and pressures they will face when they become professionals. Nevertheless, from the comparison of the overall scores of the scale, before and after the campaign, it was clear that there was an increase in the cost-conscious perception (P = .001), at the second moment. In addition, the comparison of answers points to significant changes in 5 of the 8 items of the scale. These results demonstrate the importance of the campaign for medical education.

This study demonstrates that most students disagree with the premise that physicians should try not to think about the cost to the health system when making therapeutic decisions, and agree that the practice of ordering tests and treatments are important elements of the high costs in health care. It is also observed that this perception of students was more significant after the educational actions of the CW campaign (P = .001).

The perception of this cost-conscious attitude may not perpetuate into medical practice.18,19 The authors who designed the cost-conscious attitudes questionnaire used in this article, Leep Hunderfund et al.,19 in the United States, published a study involving 2556 physicians and 3395 students, in which they demonstrate that only 22% of students disagreed that physicians should try not to think about the cost to the health system when making therapeutic decisions, compared to 41% of physicians disagreeing, regardless of their age group and length of practice. The students’ answers suggest that they are more accepting of cost-conscious care, compared to physicians, and this can be attributed to the combined effects of the insertion of this theme in the medical school curricula; to inexperience for being in training and not yet inserted in practice, but also for not facing the patient’s needs and the obstacles of the health system.

In this study, it is observed that students also strongly agreed that the act of trying to contain costs is a responsibility of every physician, reported by 82.7% and by 87.8% before and after the implementation of the CW campaign, respectively. Leon-Carlyle et al.,20 in 2019, in a study involving Harvard Medical School and University of Toronto, also demonstrated high agreement (96.4%), regarding the need for physicians to be familiar with cost-conscious decision-making at all phases of training; however, these were third and fourth year undergraduate students.

This perception on the part of students regarding the responsibility of physicians in terms of containing costs should be addressed since the undergraduate phase.19,20 Currently, students are encouraged to present long lists of differential diagnoses, emphasizing the breadth of knowledge and possibilities of tests and treatments, without considering, many times, conscious decision making based on the patient’s clinical picture. Other authors recommend that cost-consciousness should be taught as a positive professional value in order to support more reflective practices for future generations of physicians.20,21 In this context, in the cited study at Harvard and Toronto universities,20 it was shown that 84.8% of the students reported that they had seen very little inclusion of the cost approach in health care, 82.5% wanted it included in the formal curriculum, and 91% thought it was important for the future of their medical practice.

In order for physicians to contain health costs, it is also necessary that they are aware of the costs of tests and treatments.7,21 In this study, the level of agreement that physicians should be aware of the costs of the tests or treatments they recommend was high, corresponding to 98% and 100% before and after the implementation of the CW campaign, respectively. Due to the high agreement even before the campaign, no significant change was observed after the educational actions. Another study showed that this perception was different in the observed answers of students (97%) and physicians (76%), thus indicating that this reflection may not perpetuate during medical practice.19

The ABIM reported that 73% of physicians recognize that excessive testing and procedures are a problem for the health system; 72% reported ordering an unnecessary test or procedure at least once a week and 30% several times a week; 87% reported that they always or almost always talk to patients to avoid this excess of tests, but 53% would indicate the test if the patient insisted on requesting it. Physicians who saw less than 100 patients per week were more likely to refuse a test ordering, compared to those who saw more than 100 patients per week. Among the justifications cited for this practice were: fear of lawsuits, just to be on the safe side, and lack of time to talk to the patient.22

One of the causes of high costs for the health system is the inappropriate indication of medications, without analyzing the efficacy, safety, and cost of treatment options. Schutte et al.,23 in 2017, aiming to evaluate knowledge of medication costs, showed that students were less aware of the cost than physicians. Most physicians (84%) were able to identify at least 1 source of information, while students cited it at 40%. However, few students and physicians correctly estimated drug costs, especially for generic drugs (5.4%) compared to brand-name drugs (13.7%).

The need to include issues such as cost-effectiveness and more conscious and high value care in medical training has led the American Association of Medical Colleges and Internal Medicine High Value Care to implement these principles in the curriculum of medical schools and make these competencies essential for training. Nonetheless, most physicians still evaluate these initiatives as ineffective.24,25

Currently, there are increasing initiatives to involve patients and society about health care costs and the need for shared decision-making. This active participation of physicians and patients, as well as the involvement of health institutions, plays a fundamental role in actions to reduce the use of unnecessary procedures.7,10 In this study, it was observed that most students agreed that the physician should talk to patients about costs when discussing treatment options, as well as consider the cost to society before deciding whether or not to use a given intervention, with significant changes in answers after the educational actions (P = .02).

The CW campaign, used in this study as an educational intervention, has involved the patient and society to reflect on the excessive use of tests and procedures, aiming at a joint decision, improving the physician–patient relationship and also promoting care centered on the individual. Accordingly, with this shared decision, it is evident the proposal of a medicine that enables physicians and individuals to choose wisely, to analyze the risks and benefits of each procedure, and consequently, a more cost-conscious medicine.7,26

The implementation of the CW campaign in medical schools is being successfully developed in some countries around the world, thus motivating students to reflect and question about the harm that excessive testing and treatment can cause to patients.10 There is evidence that this initiative can improve students’ perceptions of patient care, as demonstrated by Colla et al.,27 in 2016, in a study with the participation of 584 physicians, in which 92% of primary and specialty care professionals agreed that the campaign is a legitimate source of guidance, and 75.1% of primary care physicians admitted that the recommendations enable them to reduce the use of unnecessary tests and procedures.

In today’s world, an exponential growth of technological resources in health care is observed, generating overuse of diagnostic procedures (overdiagnosis) and overuse of therapeutic procedures (overtreatment), resulting in increased costs. Therefore, medical education has a fundamental role in the formation of students with cost-conscious attitudes, which must be based on well-founded practices that have the quality of health care provided to the individual as a major aim. Physicians must be judicious when making daily choices in their practice, reflecting not to apply all resources, to an unlimited degree, to all patients, often inappropriately or to obtain minimal potential benefit.28,29

The present study, mainly because it is longitudinal, shows that, not only because they are students and not in a position of vulnerability, the answers were positive. Comparing the immediate answers after the CW campaign and after 1 year of medical practice, it is possible to observe that there are changes in the participants’ evaluations. However, despite the reduction in the mean, it was observed that the perception of cost-conscious attitudes remained high. Finally, it is noteworthy that when a focus occurs during graduation, trained physicians will act in a more cost-conscious manner. When there is a previous and systematized knowledge, the practice becomes more natural.30

The current study has some limitations. One of them was the short time between the intervention and the final analysis, which could potentially overestimate the perception of cost-conscious attitudes among graduated physicians. Additionally, it's important to consider that the data were collected from participants from a single educational institution, which limits the possibilities of generalizing the results.

ConclusionsAs students, the participants in this study demonstrated a high perception of cost-consciousness, even before the implementation of the CW campaign. Nevertheless, after the educational actions, a significant difference was observed in some items, thus indicating an increase in this perception at the second moment.

After 1 year of medical practice, it was possible to observe a reduction in the perception of the cost-conscious attitudes of physicians who had been sensitized, as students, by the CW campaign. However, they were shown to remain with a high perception of cost-consciousness.

Studies like this one support the idea that there is a perpetuation of cost-conscious knowledge when this theme is addressed during the undergraduate phase. New studies on this subject can be conducted to deepen the understanding of the effectiveness of this type of intervention, especially in the long-term.

Ethical statementWe declare that this research has been evaluated and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Bahiana School of Medicine and Public Health (CAAE: 34934020.0.0000.5544).