Postgraduates play an important role in reporting adverse events connected with medical devices. Many postgraduates are unaware of the present MATERIOVIGILANCE PROGRAMME OF INDIA, which was launched by the Indian Pharmacopeia Commission to monitor adverse events due to medical devices for patient safety. However, there is currently not much-published data on their knowledge, attitude, and practice of materiovigilance in India. This study's objective is to evaluate postgraduate knowledge, attitudes, and practices on materiovigilance in a tertiary care hospital.

Material and methodsThis cross-sectional, descriptive study was carried out with postgraduates. A validated, self-administered questionnaire was given to 73 postgraduates. Postgraduates were the volunteers, provided with a sheet containing 25 pre-validated questions with a time limit of 30 min. There were 10 questions based on knowledge, 8 based on attitude, and 7 based on practice to improve the reporting of medical device adverse events (MDAEs).

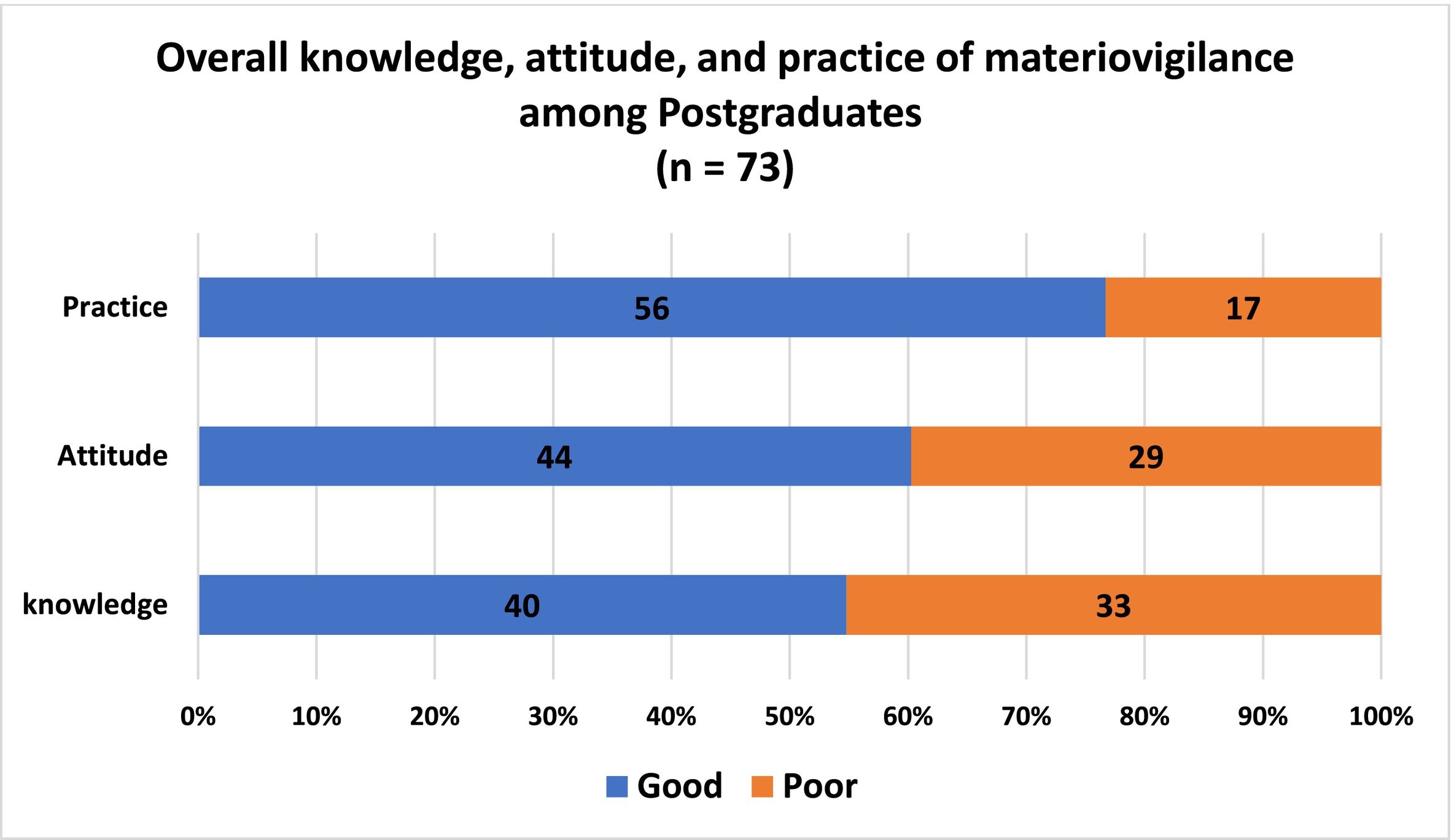

ResultsA total of 73 (100%) responses were received. About 55.41% (n = 40) of postgraduates had adequate knowledge about the various aspects of materiovigilance and 59.46% (n = 44) of postgraduates had a positive attitude towards MDAE reporting. However, 77.03% (56) of postgraduates have good practice towards MDAEs.

ConclusionAmong postgraduates, the attitude towards materiovigilance was optimal. Postgraduates who participated in this study had adequate knowledge and practice of materiovigilance. Adequate training and continuous medical education are needed to improve the current standards of knowledge and practice of materiovigilance.

Los posgrados desempeñan un papel importante en la notificación de eventos adversos relacionados con los dispositivos médicos. Muchos posgraduados desconocen el actual PROGRAMA DE MATERIOVIGILANCIA DE LA INDIA, que fue lanzado por el IPC para monitorear eventos adversos debidos a dispositivos médicos para la seguridad del paciente. Sin embargo, actualmente no hay muchos datos publicados sobre su conocimiento, actitud y práctica de materialvigilancia en la India. El objetivo de este estudio es evaluar conocimientos, actitudes y prácticas de posgrado sobre materialvigilancia en un hospital de tercer nivel de atención.

Material y métodosEste estudio descriptivo transversal se realizó con posgraduados. Se entregó un cuestionario validado y autoadministrado a setenta y tres posgraduados. Los posgraduados fueron los voluntarios, a quienes se les entregó una hoja que contenía 25 preguntas prevalidadas con un tiempo límite de 30 minutos. Hubo 10 preguntas basadas en conocimientos, 8 basadas en actitudes y 7 basadas en la práctica para mejorar la notificación de eventos adversos de dispositivos médicos [MDAE].

ResultadosSe recibieron un total de 73 (100%) respuestas. Alrededor del 55,41% (n = 40) de los posgraduados tenían conocimientos adecuados sobre los diversos aspectos de la materialvigilancia y el 59,46% (n = 44) de los posgrados tenían una actitud positiva hacia la notificación de eventos adversos de dispositivos médicos (MDAE). Sin embargo, el 77,03% (56) de los posgrados tienen buenas prácticas hacia los MDAE.

ConclusiónEntre los posgraduados, la actitud hacia la materialvigilancia fue óptima. Los posgraduados que participaron en este estudio tenían conocimientos y práctica adecuados de materialvigilancia. Se necesita una formación adecuada y una educación médica continua para mejorar los estándares actuales de conocimiento y práctica de la materialvigilancia.

Following the thalidomide catastrophic events in 1961, there have been concerns concerning patient safety when utilizing pharmaceuticals. As a result, the Program for International Drug Monitoring in 1968 and the United Kingdom's Committee on Drug Safety were established in 1963 by World Health Organization (WHO).1 Subsequently, the WHO extended the Pharmacovigilance program globally to more than 150 countries and also included biologicals in 1947,2 vaccines in 1999,3 and medical devices in 2003.4

Materiovigilance refers to a combined system that characterizes performance, monitors, identifies, collects, reports, and analyzes any untoward occurrence caused by medical devices.5

WHO defines the medical device as “an article, instrument, apparatus, or machine used in the prevention, diagnosis, or treatment of illness or disease, or for detecting, measuring, restoring, correcting, or modifying the body's structure or function for a health purpose.”6 Medical devices have become crucial when it comes to the detection, monitoring, and medical management of various illnesses.7

Medical devices involve simple bandages, syringes, heart pacemakers, coronary stents, magnetic resonance imaging, and software applications.8

Established in 2011 by a coalition of 10 countries, including the USA, Japan, EU member states, China, South Korea, and India, the International Medical Device Regulators Forum aims to standardize global regulations for medical devices. It focuses on implementing a comprehensive program to monitor medical device adverse events (MDAEs) to strengthen oversight, ensure patient safety, and advance healthcare technology worldwide.9 Globally, reporting MDAEs is critical for patient safety, with varying requirements across regions: USA to the FDA,10 Europe to NCAs,11 Canada within specific timelines,12 Australia up to 5 years,13 Japan within 2 weeks,14 China to CFDA,15 and in India, reporting remains voluntary for most stakeholders, with mandatory reporting of serious events to the CDSCO.16

The Drugs Controller General India formally launched the Materiovigilance Program of India (MvPI) at the Indian Pharmacopeia Commission (IPC) in Ghaziabad on July 6, 2015.17 The IPC is an autonomous entity of the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare. It additionally operates as the National Coordination Centre for India's Materiovigilance Programme.17 The National level Collaborating Centre for materiovigilance [MvPI] is Sree Chitra Tirunal Institute of Medical Sciences & Technology.17 WHO Collaborating Centre for Priority Medical Devices and Health Technology Policy, offers technical support for this program through the Healthcare Technology Division, National Health System Resource Centre, New Delhi.17 174 MEDICAL DEVICE ADVERSE EVENT MONITORING CENTRE (MDMCs) in the country have been selected to report any untoward occurrences related to the use of medical devices. IPC developed a standard reporting form ‘Medical Device Adverse Event Reporting Form’ to collect, monitor, and report these untoward events related to medical devices.17

Postgraduates play an important role in reporting MDAEs. The existing MATERIOVIGILANCE PROGRAMME OF INDIA, which was established by the IPC to monitor adverse events associated with medical devices for patient safety, is not widely known among postgraduates. There was not enough research done on postgraduate students in understanding, perspective, and behavior (KAP) about materiovigilance. On the other hand, there was not an abundance of publicly available data at present on their knowledge, attitude, and practice of materiovigilance in India.

Materials and methodsStudy design and settingThis study was performed using a questionnaire at a tertiary center. The Institutional Ethics Committee approved the study protocol, and the study was carried out between December 2023 and February 2024 (3 months).

Study tool: Questionnaire and validationA 25-item structured questionnaire was developed by the faculties of the Department of Pharmacology. The questionnaire consists of 2 parts. Section I comprised postgraduates' demographic data (age, gender, and institution), and section II comprised 25 questions about materiovigilance under 3 domains [knowledge domain (Question no: 1–10), attitude domain (Question no: 11–18), practice domain (Question no: 19–25)]. The “knowledge” domain had 10 closed-ended questions. A score of 1 was allocated for each correct response, whereas there was no negative score for the wrong response (Question no: 2–9). Question no: 1 and 10 which can be answered by simple “yes or no”. The mean knowledge score was calculated. Attitude and practice were assessed by closed-ended questions which can be answered by simple “yes or no”, where a score of 1 for “yes” and 0 for “no” were given.

An expert panel validated the questionnaire's validity in terms of content, highlighting the questions' relevance, clarity, and simplicity of usage. The relevance, feasibility, comprehension, and clarity of the questionnaire were evaluated by pilot-testing it on 30 postgraduates. The final analysis of the study results did not include the responses obtained from the pilot study participants. Using Cronbach's alpha, the questionnaire's reliability and internal consistency were assessed. Cronbach's alpha (α=0.67) suggests its adequate internal consistency.

Ethical approvalAfter obtaining approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee, the study was initiated. The postgraduate students were approached, and given information regarding the study, and those who volunteered were included as participants in this study.

Study participantsInclusion criteriaPostgraduates who were given informed consent to participate in this study were included.

Exclusion criteria- 1.

Postgraduates who were not available when the questionnaire was distributed.

- 2.

Those who were not willing to participate.

- 3.

Postgraduates who participated in the pilot study were also excluded from the study.

The prevalence of knowledge of materiovigilance among the postgraduates was 46%, from the pilot study. Using this knowledge prevalence from the pilot study and assuming a confidence interval of 95%, absolute precision of 5%, and non-response rate of 10%, the final sample size calculated for this study was 73. Open Epi software version 3 was used to calculate the sample size. (Open-Source Epidemiologic Statistics for Public Health, www.openepi.com).

Data collectionThe objective of the study was made clear to the postgraduates, and those who decided to participate in the questionnaire study obtained informed consent. The study participants received the finalized version of the questionnaire together with the necessary instructions to complete it anonymously. Postgraduates were given instructions to hand in completed questionnaires the same day, or the next morning if they were busy. Confidentiality of the collected data was ensured by submitting the completed questionnaire in a sealed container kept in their department.

Statistical analysesThe study participants' responses were coded using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 21.0) (IBM, New York, USA). The normality of the data was tested using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The results were given utilizing descriptive statistics (frequency, percentages, median+interquartile range). Chi-square was used to find an association between knowledge, attitude, practice, and year of education.

ResultsDemographic detailsAll 73 questionnaires provided were completed and returned, which gave a 100% response rate. Study participants were more or less equal females (n=36, 49%), and males (n = 37, 51%).

Postgraduate's knowledge towards materiovigilanceAbout 49.31% (n=36) of them were aware of the materiovigilance and 80.82% (n=59) were aware of the ongoing program for monitoring medical device-related adverse events. 90.41% (n=66) and 45% (n=61.64%) were aware of the year of materiovigilance launched and the national collaborating center for MvPI, respectively. However, only a few 17.89% (n=13) were aware that the regulatory authority oversees materiovigilance activities for medical devices in India. About 84.93% (n=62) are aware of the year in which the medical device rule was approved. Only 30.13% (n=22) were aware that on what basis medical device-related adverse reactions are classified. About 67.12% (n=49) were able to identify category C. Only a handful of them [32.87% (n=24)] were aware that the adverse events due to a medical device can be reported (Fig. 1). About 54.79% (n=40) of postgraduates had adequate knowledge, based on the overall knowledge level of the study participants (Table 1; Fig. 2). About 58.33% (21) females and 41.67% (15) males have adequate knowledge about materiovigilance.

The majority 91.78% (n=67) of the postgraduates agreed that medical devices can produce adverse events in patients and about 97.26% (n=71) agreed that reporting will enhance patient safety in the future. Almost most of the postgraduates 98.63% (n=72) agreed that it is necessary to report these adverse events and 97.26% (n=71) think that it is the responsibility of doctors to report MDAEs. About 95.89% (n=70) agreed to establish a materiovigilance monitoring center in every hospital. At the same time, around 73.97% (n=54) think that healthcare professionals generally do not have enough time for MDAE monitoring and reporting. About 95.89% (n=70) agreed that the need for periodical conduct of awareness will reduce MDAE. 93.15% (n=68) of postgraduates agreed upon the inclusion of materiovigilance in the UG/PG curriculum (Fig. 3). Overall, about 60.27% (n=44) have a positive attitude towards materiovigilance (Table 1;Fig. 2). About 58.33% (21) females and 59.46% (22) males have a positive attitude towards materiovigilance.

Postgraduate's practice towards materiovigilanceAround 24.65% (n=18) have seen the MDAE reporting form and 20.54% (n=15) have been trained regarding reporting of MDAEs. About 41.09% (n=30) have witnessed adverse events related to medical devices during their clinical posting. Only a few 23.28% (n=17) have reported. Only 21.91% (n=16) have attended CME/CONFERENCE regarding materiovigilance. 71.23% (n=52) have agreed to participate in activities like campaigns. About 78.08% (n=57) take feedback for any untoward events from patients after implanting the device (Fig. 4). Overall, about 76.71% (n=56) of postgraduates have good practice towards materiovigilance (Table 1; Fig. 2). About 86.11% (31) females and 67.57% (25) males have good practice towards materiovigilance.

DiscussionAcross the world, it is believed that maintaining an organized active surveillance system for medical devices is essential for enhancing both their quality and safety. Additionally, each of these methods serves to enhance patient safety and the healthcare system.18–20 Additionally, studies done on healthcare professionals (HCPs) in other nations show inadequate MDAE reporting practices and a lack of understanding.21–23 As a result, the current study aimed to analyze the KAP of materiovigilance among postgraduates working in a tertiary care hospital.

A response rate of 100% was obtained in this study, which appears to be exceptionally high compared with the response rates reported in earlier studies.21–23 Participants [55.41% (n=40)] had an adequate level of knowledge regarding the various aspects of materiovigilance in this present study. This is relatively higher than the values reported in similar studies carried out by Meher et al.18 The majority of the participants (77.7%, n=56) in our study had a positive attitude towards MDAE reporting, and a similar trend was observed in the studies done by Meher et al.18 Our study participants' high response rate, sufficient knowledge, along a positive attitude towards materiovigilance are encouraging signs of their interest and sense of accountability.

Although 23.28% (n=17) of postgraduates during their practice in the current study reported MDAE in patients, 47.94% (n=35) of them had experienced the incidence of MDAE. The results correspond with the findings reported in previous studies.18–20 When comparing total scores based on years, final-year postgraduates scored significantly higher than the other participants. This is possible because they encounter more MDAE involved in patient management than junior postgraduates.

Adverse events associated with medical devices undergo systematic monitoring through periodic reporting cycles—monthly, yearly, and upon incident occurrence—to detect emerging trends, promptly identify issues, and evaluate the effectiveness of safety protocols. Postgraduates specializing in clinical disciplines such as medicine, radiology, and surgery progress from mastering materiovigilance principles to effectively identifying and managing device-related issues that directly impact patient care. In contrast, individuals in non-clinical fields like pharmacology focus on ensuring regulatory compliance and conducting rigorous preclinical evaluations of medical devices.

Regarding the impact of time passed since graduation (Table 2), clinical postgraduates with more experience tend to exhibit better adherence to identifying and reporting materiovigilance issues. Their accumulated clinical experience enables them to recognize and report incidents more effectively, contributing to improved patient care and safety protocols. Non-clinical postgraduates, while focusing on regulatory aspects, also benefit from experience and ongoing professional development in understanding and addressing materiovigilance concerns before devices reach clinical settings. Thus, time since graduation influences both groups' ability to adhere to materiovigilance practices, impacting their roles in patient safety and regulatory compliance within their respective professional domains.

MDAE was severely underreported due to factors such as uncertainty on how to report such along with worries about their legal issues. These deficits indicate the need to organize workshops and training sessions to sensitize and encourage postgraduates on spontaneous and regular reporting of MDAE encountered. Furthermore, it is essential to periodically evaluate the impact of these training sessions on the quality of reports received at MDAE monitoring centers.

Posters/Banners at the ward featuring information on what to do when MDAE occurs is another approach that can be used to encourage MDAE reporting. On the contrary, postgraduate students need to be made aware of the MDAE reporting forms that are available on the IPC website. These forms may be downloaded, which will speed up and simplify the reporting procedure overall.24 Future healthcare workers can be made aware of the importance of medical device surveillance early on by incorporating materiovigilance into their undergraduate curriculum.

A small sample size, single-center study, and inclusion of only postgraduate students were some of the study's limitations. Future multicentric, large-scale prospective research which includes all sorts of HCPs might validate our preliminary results. The impact of awareness campaigns and training sessions on MDAE reporting by HCPs can also be explored further.

ConclusionIn this study, it has been observed that among postgraduates, the attitude towards materiovigilance was optimal. The postgraduates who participated in this study had adequate knowledge and practice of materiovigilance. Despite the current limitations and multiple contributors, it is necessary to implement targeted training workshops for postgraduate students to enhance their understanding and application of materiovigilance principles. Launch focused awareness campaigns emphasizing the importance of prompt reporting of MDAEs. Integrate materiovigilance into postgraduate healthcare curriculum for comprehensive education. Simplify reporting processes with user-friendly tools tailored for postgraduates. These steps collectively aim to strengthen materiovigilance initiatives and elevate patient safety standards at the hospital.

FundingThis study received no funding.