The term, “learning styles” refers to the concept that individuals have as regards the method of instruction or study that is most efficient for them. It has been proposed that optimal learning occurs when the preferences of the primary learning style of the student correspond to the course content and the method of instruction. The Visual, Aural, Written/Read and Kinesthetic (VARK) model is a preferred instruction model. The objective of the study was to investigate the relationship between the VARK preferences and the Gross Anatomy test results of a group of students from the Universidad del Norte. The study included 111 (61 female and 50 male) students enrolled in their third semester of medical school in the skeletomuscular system during the summer of 2015. The VARK Aural and Kinesthetic modes were the most common (34.2% and 26.1%, respectively), while Visual was the learning style with the lowest number of representatives (9%). The multimodal style was preferred by 12.6% of the students involved. There was no significant statistical relationship (X2=2.61; p=.62 and X2=5.4; p=.24) between the VARK modes and the mid-term test results. The Aural and Kinesthetic modes showed significant negative correlations with the mid-term electronic multiple-choice assessment (rs=−0.19; p=.03; and (rs=−0.24; p=.01). Although different teaching strategies were offered to the students, no significant differences were observed. However, the students with Aural and Kinesthetic modes did show a negative correlation with the mid-term electronic multiple-choice assessment.

El término «Estilos de aprendizaje» se refiere al concepto que los individuos difieren en cuanto a qué modo de instrucción o estudio es más eficaz para ellos. Se ha propuesto que el aprendizaje óptimo ocurre cuando las preferencias del estilo de aprendizaje primario del alumno se corresponden con el contenido del curso y el modo de instrucción. El modelo «visual, aural, lectura/escritura y kinestésico» (VARK) es un modelo de preferencia instruccional. El objetivo de este estudio fue investigar la relación entre las preferencias VARK y los resultados de la evaluación en anatomía macroscópica de un grupo de estudiantes de la Universidad del Norte. El estudio incluyó a 111 (61 mujeres y 50 varones) estudiantes de tercer semestre de medicina inscritos en el módulo del sistema osteomuscular durante el verano de 2015. Las modalidades VARK aural y kinestésica fueron las más frecuentes (34,2 y 26,1%, respectivamente) mientras que «visual» fue el estilo de aprendizaje con el menor número de representantes (9%). El estilo «multimodal» comprende el 12,6% de los estudiantes involucrados. No hubo relación estadísticamente significativa (X2=2,61; p=0,62, y X2=5,4; p=0,24) entre las modalidades VARK y los resultados del examen de mitad de período. Las modalidades «auditivas» y «kinestésicas» mostraron correlaciones negativas significativas con la evaluación parciales electrónicas de selección múltiple (rs=−0,19; p=0,03, y rs=−0,24; p=0,01). Aunque se ofrecieron diferentes estrategias de enseñanza a los estudiantes, no se observaron diferencias significativas; más sin embargo, los estudiantes con modalidades «aural» y «kinestésica» mostraron una correlación negativa con las evaluaciones parciales electrónicas de selección múltiple.

The term “learning styles” refers to the concept that individuals differ in regard to what mode of instruction or study is most effective for them.1 Psychologically, learning style is the way the student concentrates, and their method in processing and obtaining information, knowledge, or experience.2 As an educational tool, learning styles follows three steps: (1) individuals will express a preference regarding their “style” of learning, (2) individuals show differences in their ability to learn about certain types of information, and (3) the “matching” of instructional design to an individual's learning style will result in better educational outcomes.3 It has been proposed that optimal learning occurs where the primary learning style preferences of the learner are matched with course content and mode of instruction.1,4 The most common-but not the only-hypothesis about the instructional relevance of learning styles is the meshing hypothesis.1,5 According to the meshing hypothesis, instruction is best provided in a format that matches the preferences of the learner. Despite the evidence that has been published against the “learning styles”,6 94% of educators believed that students perform better when they received information in their preferred learning style.7

The Visual, Aural, Read/Write, and Kinesthetic (VARK) model is an instructional preference model, which is designed to identify four sensory modalities.8 Each of them has its own characteristics: (a) the Visual learners prefer the use of graphics, videos and images to learn; (b) Aural learners give particular attention to words; (c) Read/Write learners like lecture notes and text books; (d) Kinesthetic meanwhile use hands on experience, practical application and use of models.2,9 A number of researchers have utilized the VARK questionnaire to explore relationships between VARK learning preferences and academic performance among health care students10 with diverse results. Some have found no relationship between learning styles and academic performance10–12; others have demonstrated in medical education that students with multiple learning preferences show improved academic performance.13,14 Gender, cultural and demographic differences have also been reported.13,15–17

Assuming that there is a relationship between learning styles and the results of assessments, it could be hypothesized that students with visual learning preferences would have a better performance in theoretical and laboratory assessments of gross anatomy. The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between VARK preferences and gross anatomy assessment outcomes in a group of 3rd semester students at the Universidad del Norte in Barranquilla, Colombia, to whom different modes of instruction were provided.

MethodsCurricular designAt the Universidad del Norte's School of Medicine, all students admitted already had 12 years of secondary education, which was the entry level for the university. The university receives students from the entire Caribbean coast of Colombia, so some academic differences may exist, but culturally they are very similar. The twelve-semester curriculum is divided into two components: a basic science portion, during the first five semesters, which is conducted mainly at university facilities; and a clinical portion in which students attend another seven semesters participating in clinical learning experiences at various teaching hospitals. In the basic sciences component, we have a system approach or modules (musculoskeletal, nervous system, etc.), and in each module all subjects (anatomy, histology, pathology, etc.) are integrated.18

Study designThe study involved 111 (61 women and 50 men) third semester medical school students (aged 17–19 years old) enrolled in the musculoskeletal system module during the summer of 2015 at the Universidad del Norte. Forty-four hours were devoted to human gross anatomy in the musculoskeletal module (22 lecture hours, 20h of gross anatomy laboratory and 4h of clinically oriented case discussion). Lectures were conducted in lectures halls with a 60-student capacity and usually were teacher centered based on PowerPoint and video presentations. In the gross anatomy laboratory sessions, an average of 30 students participated and were usually based on projections and supported by the use of anatomical software like A.D.A.M. Interactive Anatomy (1991–1997 ADAM 3.0, A.D.A.M. Software, Inc., Atlanta, GA), VH Dissector (Touch of Life Technologies Inc. 2012) and Complete Anatomy (3d4medical.com). Clinically oriented cases were designed by the two instructors in Anatomy and delivered to students using the Blackboard platform (Blackboard CE8, Blackboard Inc., Washington, DC).18 In the first academic session, all the students were instructed by the lead author (EGM) about learning styles, how they are classified regarding to VARK learning preferences and tips to better learn according to each one. Students were invited to participate and identified his/her own learning style through an online VARK questionnaire in Spanish (http://vark-learn.com/el-cuestionario-vark/) and submitted the result to the authors. During six lectures and nine laboratory sessions (100min each), materials that appeal to different learning environments (power-point presentations, apps located on the university website, videos, audios, text book chapter readings, atlases, laboratory guides, cadaver projections and models) were provided and available for students during the remainder of the semester. Every four weeks on average, all students performed an electronic closed book examination with 20 multiple-choice questions taken from a set of faculty peer-reviewed questions (E) as well as a practical laboratory test (L). The electronic assessment questions were the same for all, but for practical reasons, the students in practical laboratory test were divided in two groups. The assessment was tag test mode and the questions had the same level of difficulty and were about the same topics for both groups. Students should identify the anatomical landmarks and write them on a sheet of paper provided by EGM. The maximum score on the mid-term examinations was 5.0, and this was obtained by the summation of 4.0 from the electronic examination and 1.0 from the practical laboratory test. Each mid-term examination was equal to 25% of the total grade, and the final grade was calculated based on the summation of the 4 mid-term examination grades. The pass/fail cutoff value was 60% of the maximum grade on each examination.

Statistical analysisTo evaluate the possible effect of learning styles on gross anatomy assessment outcomes, cross-tabulations and chi-square tests were used to compare the VARK distributions for gender as well as the electronic and practical examination scores. Correlations between VARK distributions and assessment scores were analyzed.

For the assignment of the type of learning style, the 16 questions of the questionnaire were taking into account and the prevalent modality was chosen, that is to say, the one that showed the highest frequency or the highest modal score.

Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS statistical package, version 21 (IBM Software Group, Chicago, IL).

ResultsFrom 117 third semester medical school students enrolled in the musculoskeletal system module during the summer of 2015, only 111 (50 men and 61 women) completed the VARK questionnaire. All of the students who completed the VARK questionnaire performed the mid-term electronic multiple-choice assessment, but only 109 did the practical laboratory assessment.

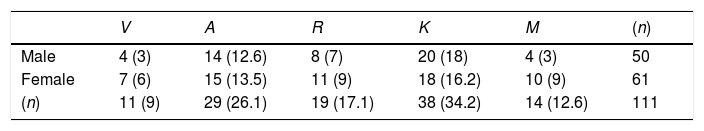

Gender distribution and learning stylesTable 1 summarizes the number and percentage of total respondents according to age and VARK modes. Eleven percent (11%) of the students were estimated to show an imbalance because a single modal category did not predominate, while 71% showed equilibrium due to a modal preference. Kinesthetic and aural were the VARK modalities with the greatest number of students (34.2% and 26.1% respectively) and visual was the learning style with the fewest representatives (9%). Multimodal comprised 12.6% of the students involved. In all modes but kinesthetic, women outnumbered men.

Gender distribution by learning style (VARK modes).

| V | A | R | K | M | (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 4 (3) | 14 (12.6) | 8 (7) | 20 (18) | 4 (3) | 50 |

| Female | 7 (6) | 15 (13.5) | 11 (9) | 18 (16.2) | 10 (9) | 61 |

| (n) | 11 (9) | 29 (26.1) | 19 (17.1) | 38 (34.2) | 14 (12.6) | 111 |

VARK modes. V=visual; A=aural; R=read/write; K=kinesthetic; M=multimodal. (n)=number of students who completed the test; figures=%.

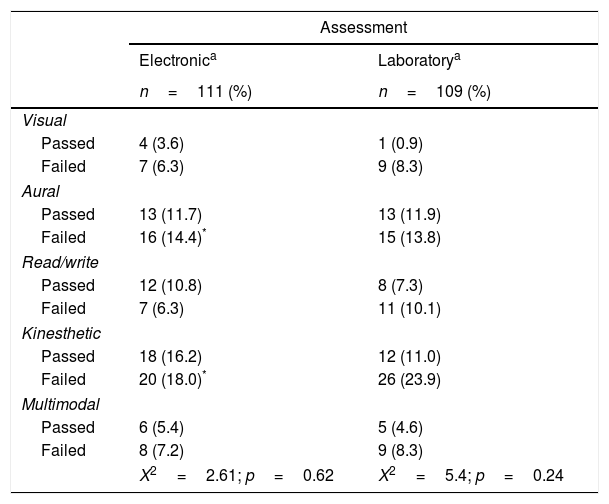

Table 2 describes the association observed between the learning style modalities and the mid-term examinations. Although there was no statistically significant relationship (X2=2.61, p=0.62, and X2=5.4, p=0.24) between the VARK modalities and the mid-term examination scores, it can be seen that the students with aural and kinesthetic mode passed and failed the mid-term electronic multiple-choice assessment and the practical assessment almost in equal number, and they had the highest scores. By contrast, visuals had the lowest. Aural and kinesthetic modalities showed significant negative correlations with the mid-term electronic multiple-choice assessment (rs=−0.19, p=0.03 and rs=−0.24, p=0.01).

Assessment outcomes and learning styles.

| Assessment | ||

|---|---|---|

| Electronica | Laboratorya | |

| n=111 (%) | n=109 (%) | |

| Visual | ||

| Passed | 4 (3.6) | 1 (0.9) |

| Failed | 7 (6.3) | 9 (8.3) |

| Aural | ||

| Passed | 13 (11.7) | 13 (11.9) |

| Failed | 16 (14.4)* | 15 (13.8) |

| Read/write | ||

| Passed | 12 (10.8) | 8 (7.3) |

| Failed | 7 (6.3) | 11 (10.1) |

| Kinesthetic | ||

| Passed | 18 (16.2) | 12 (11.0) |

| Failed | 20 (18.0)* | 26 (23.9) |

| Multimodal | ||

| Passed | 6 (5.4) | 5 (4.6) |

| Failed | 8 (7.2) | 9 (8.3) |

| X2=2.61; p=0.62 | X2=5.4; p=0.24 | |

This study explored the association between learning styles using VARK model and academic performance in a cohort of third semester medical students at Universidad del Norte in Barranquilla, Colombia.

Learning styles are styles or individual learning techniques that act with the environment, to process, interpret and obtain information, experiences, or desirable skills while taking into consideration individual factors such as gender, age, and personality as well as heritage, race, and environment influence; namely, influence from their parent's education, culture, community, and school.2 The VARK inventory has been determined to be a reliable tool in terms of correlation of sensory preferences between scenarios, although further concerns have been raised regarding the variability of responses between differing student cohorts.19 In Colombia little research has been conducted in this field, therefore, publications are limited20 and there have been no published reports on medical students.

Inconsistency of VARK learning preferences between different cohorts of students should be expected.19 This study, in common with results reported by others,9,12 failed to provide a strong association between learning style and summative anatomy assessment performance.

Academic performance has been shown to be significantly better for students whose learning style matches the dominant course component.21,22 Students traditionally have used anatomy textbooks, which usually contain a myriad of colored drawings, images, photographs and radiographs, as well as atlases and dissection manuals to study anatomy.23 Although diverse teaching strategies were delivered to the students, no significant differences were observed; nevertheless, students with aural and kinesthetic VARK modalities showed a negative correlation with the mid-term electronic multiple-choice assessment. In this study as well as in previous reports,10,24 the predominant sensory modality of learning was kinesthetic (34.2%) and aural (26.1%). The kinesthetic and aural learning preference have been negatively associated with performance when kinesthetic activities are de-emphasized19 because kinesthetic individuals prefer to learn through direct practice, which may also involve the other perceptual modes.25 Due to the peculiarities of anatomy teaching at the Universidad del Norte, the authors expected a better performance in students with a visual style, although, as has been reported by others,26 the kinesthetic modality includes the preference to work with models, simulations or photographs, which is present in the practice of our students. The authors have no clear explanation about these results, because many factors can influence them. Although somewhat speculative, one explanation could be that a greater number of medical students in Colombia are using smartphones to record lectures, transcribe and print them at home later, which stimulates the aural style. This could potentiate aural and read/write modalities and this is why students with the read/write mode had the second best score in this sample. Another explanation could be that at the Universidad del Norte, the possibilities to work with cadavers at the laboratory are reduced due to the limited supply of specimens.

Study limitationsThe results reported are limited to this sample and to the Universidad del Norte academic context. This study had several limitations, including the low sample size, the lack of control in regard to previous academic performance, and an active effort to determine whether the combination of different teaching methods used were adequately addressed to the different types of learning. Although VARK has involved implicit engagement and motivation, these aspects were not explored either.

ConclusionThe results reported here are the first in a Colombian medical student sample. These data failed to provide a strong association between learning style and summative anatomy assessment performance. Although students with aural and kinesthetic VARK modalities showed a negative correlation with the mid-term electronic multiple-choice assessment, there is no clear evidence that a particular learning style conferred a material advantage in summative assessment of anatomy learning.

Conflict of interestThe authors of this article declare no conflict of interest.