There is an increasing interest in the usefulness of humanities to improve the training of medical students. In this article, an analysis is made of the presence of humanities subjects in medical curricula of Italy and Spain.

Material and methodsA review of the curricula of the Bachelor in Medicine in Italian and Spanish universities that offered this degree was carried out by using the information available on the institutional websites. Information was collected as regards the type of subjects and the academic characteristics of the more frequently included subjects.

ResultsA total of 42 Italian and 39 Spanish universities were examined. All of them included at least one subject with humanities contents. The most frequently included were, History (91%), Philosophy (81%), Anthropology (28%), and Literature (12%). Significant differences were seen between the countries regarding the presence of some subjects and their academic characteristics. The reduced number of ECTS credits and the lack of academic independence of humanities content were common features.

DiscussionHumanities contents, mainly History of Medicine and Bioethics were present in most medical curricula of Italian and Spanish universities. However, their relative importance was considered to be low, given the ECTS credits and presence as independent subjects. Some actions are recommended to improve the presence of humanities in medical studies in Italy and Spain.

Existe un interés creciente sobre la utilidad de las humanidades para mejorar la formación de los estudiantes de medicina. En el presente artículo, se analizó la presencia de asignaturas de humanidades en los estudios de medicina en España e Italia.

Material y métodosSe revisaron los planes de estudio del grado de Medicina de las universidades españolas e italianas que lo ofrecían por medio del análisis de sus portales. Se recogió información sobre el tipo de asignaturas y las características académicas de las que aparecían con más frecuencia.

ResultadosSe examinaron 42 universidades italianas y 39 españolas. Todas incluían al menos una asignatura con contenidos de humanidades. Las más frecuentes eran Historia (91%), Filosofía (81%), Antropología (28%) y Literatura (12%) Se encontraron diferencias entre ambos países en referencia a la presencia de algunas asignaturas y a sus características académicas. Se observó, en general, la falta de asignaturas de humanidades independientes y un bajo número de créditos ECTS.

DiscusiónLos contenidos de humanidades, especialmente Historia de la Medicina y Bioética, se encontraban en la mayoría de los planes de estudio de las universidades españolas e italianas. Sin embargo, su importancia relativa era baja dados los créditos asignados y su ausencia frecuente como asignaturas independientes. Se recomiendan acciones que permitan aumentar la presencia de las humanidades en los estudios de medicina de ambos países.

Humanities have been a cornerstone in the higher education of Western societies for centuries.1 In Medieval universities, the knowledge of some humanistic disciplines was compulsory for all students, but since the eighteenth century, the development of scientific and technological disciplines focused university training around technical subjects rather than providing a broad sense of education.2 In the present century, there is a general loss of awareness of the value of humanities in the education of young people.3,4 Science, and also medicine, needs a cultural context to be better understood; humanities are the backbone of modern societies and therefore to ignore them may greatly impoverish the education of citizens.5

In recent years, it has been stated that humanities also play an important role in the training of physicians.6–8 This is not a new idea and, for example, William Osler was a strong defendant of the use of literary texts in medical education.9 It is probable that the success of medicine in allowing for better diagnoses and treatments during the last one hundred and fifty years has created the opinion that the educative needs of medical students should be exclusively directed at biomedical or clinical sciences. More recently, the inclusion of humanities in the training of physicians has been suggested.10 In fact, some subjects, such as bioethics, seem out of discussion as they may help physicians to make adequate clinical choices. However, the importance of other subjects is still disputed,7 and the evidences on their positive long-term impact on undergraduate medical students are still sparse.11

Since the introduction of humanities in medical studies in Pennsylvania State University in 1967,12 some universities have implemented such programs in Europe.13 The implementation of the European Higher European Space (EEES) provided an opportunity to review and change medical curricula. There are few evidences of how EEES affected the inclusion or exclusion of humanities subjects; with some exceptions such as Switzerland, where the reform is being used to consider medical ethics teaching and also the importance of social sciences and medical humanities.14,15 A review of how universities are considering this challenge is lacking in most countries. Therefore, the aim of this study was to analyze the current situation of humanities in the medical curricula in Italy and Spain from the qualitative and quantitative point of view.

Material and methodsSettingThe study was carried out in universities in Italy and Spain. The information on the medical curricula of each center was obtained from their institutional websites on the Internet. For the purpose of this study, we considered humanities in a broad sense, defining them as the non-medical subjects that may enhance the training of medical students, which included literature, visual arts, performing arts, philosophy, anthropology, history, and sociology.7

VariablesThe following information was obtained for each university that offered an undergraduate degree in medicine (Laurea di Medicina in Italy, Grado de Medicina in Spain) during the academic years 2014–2015 (Spain) and 2015–2016 (Italy):

- •

Type of university (public or private)

- •

Presence of subjects in humanities in the curriculum

- •

Type of subject (anthropology, history, language studies, literature, music, philosophy, religion and theology, sociology, and visual arts)

Later, the academic characteristics of the most frequently taught subjects were further analyzed, and the following information was collected for each:

- •

Number of ECTS credits

- •

Academic consideration (compulsory or elective)

- •

Academic year of the curriculum where the subject is offered (1st to 6th)

- •

Syllabus (presence or absence)

The study analyzed eighty-one universities, forty-two from Italy and thirty-nine from Spain. In Italy, only three of these were private universities and among them only the Università di Milano San Raffaele was not linked to the Italian Catholic Church. In Spain, thirty universities were public and nine were private. Only two private universities were unrelated to the Catholic Church (Universidad Alfonso X El Sabio and Universidad Europea de Madrid).

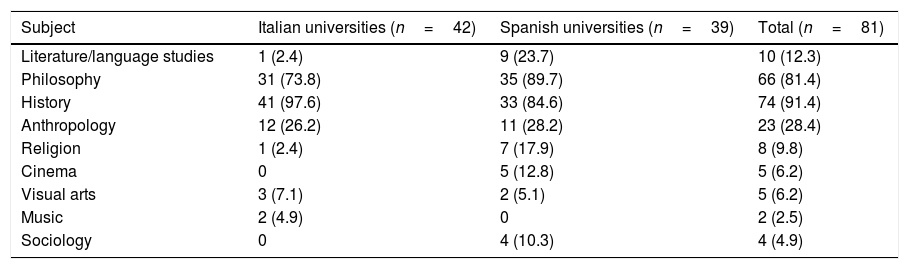

Subjects in humanitiesAll Italian and Spanish universities had at least one subject in the humanities field (Table 1). When considering all the data together, it was shown that History (mainly History of Medicine) and Philosophy (mainly Bioethics) were present in most curricula of both countries with small differences: history was more prevalent in Italy whereas philosophy was more so in Spain. Anthropology came third with a global value of 28.4%. Some differences were observed between countries. In Spanish universities, the presence of subjects related to literature (23.7%), religion (17.9%), cinema (12.8%) and sociology (10.3%) was clearly higher than in Italian universities.

Humanities in the medical curricula of Italian and Spanish universities.

| Subject | Italian universities (n=42) | Spanish universities (n=39) | Total (n=81) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Literature/language studies | 1 (2.4) | 9 (23.7) | 10 (12.3) |

| Philosophy | 31 (73.8) | 35 (89.7) | 66 (81.4) |

| History | 41 (97.6) | 33 (84.6) | 74 (91.4) |

| Anthropology | 12 (26.2) | 11 (28.2) | 23 (28.4) |

| Religion | 1 (2.4) | 7 (17.9) | 8 (9.8) |

| Cinema | 0 | 5 (12.8) | 5 (6.2) |

| Visual arts | 3 (7.1) | 2 (5.1) | 5 (6.2) |

| Music | 2 (4.9) | 0 | 2 (2.5) |

| Sociology | 0 | 4 (10.3) | 4 (4.9) |

We analyzed the content of the most frequently offered subjects, i.e. those that were present in at least five Italian or Spanish universities (Table 1). These were: history (n=74, 91.4%), philosophy (n=66, 81.4%), anthropology (n=23, 28.4%) and literature/philology (n=10, 12.3%).

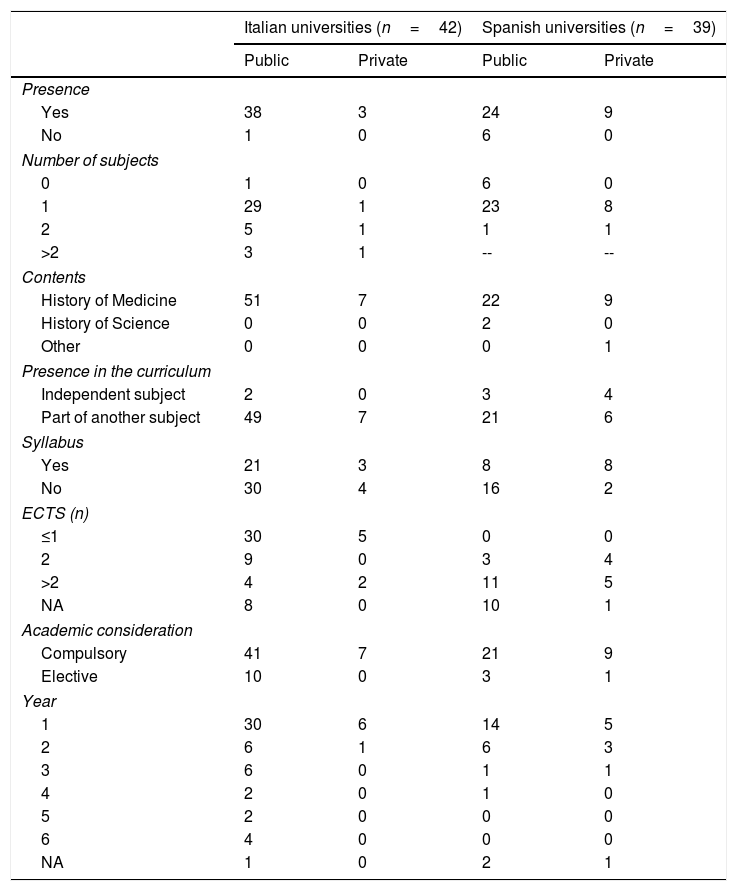

HistoryMost Spanish (84.6%) and Italian (97.6%) universities offered some training in history, mainly in History of Medicine (Table 2). Most universities offered only one subject in this area. The results differed if History was taught as a separate subject or was a part of another subject. Seven Spanish universities provided a History subject, whereas in Italy only two Universities did. The countries also differed in the number of ECTS credits. In Italy, most universities offered one or less, whereas in Spain they all offered at least two.

Characteristics of the subject History in Spanish and Italian Universities.

| Italian universities (n=42) | Spanish universities (n=39) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public | Private | Public | Private | |

| Presence | ||||

| Yes | 38 | 3 | 24 | 9 |

| No | 1 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| Number of subjects | ||||

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| 1 | 29 | 1 | 23 | 8 |

| 2 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| >2 | 3 | 1 | -- | -- |

| Contents | ||||

| History of Medicine | 51 | 7 | 22 | 9 |

| History of Science | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Presence in the curriculum | ||||

| Independent subject | 2 | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| Part of another subject | 49 | 7 | 21 | 6 |

| Syllabus | ||||

| Yes | 21 | 3 | 8 | 8 |

| No | 30 | 4 | 16 | 2 |

| ECTS (n) | ||||

| ≤1 | 30 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 9 | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| >2 | 4 | 2 | 11 | 5 |

| NA | 8 | 0 | 10 | 1 |

| Academic consideration | ||||

| Compulsory | 41 | 7 | 21 | 9 |

| Elective | 10 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| Year | ||||

| 1 | 30 | 6 | 14 | 5 |

| 2 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 3 |

| 3 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 4 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| NA | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

NA: not available.

More coincidences were seen when analysing the academic year in which the subject was offered. In both countries most of the subjects were offered in the first or second year, but some Italian universities offered history subjects in all the academic years. Regarding the academic character, the subjects were compulsory in almost all universities in both countries, even so, Italy offered ten courses as electives.

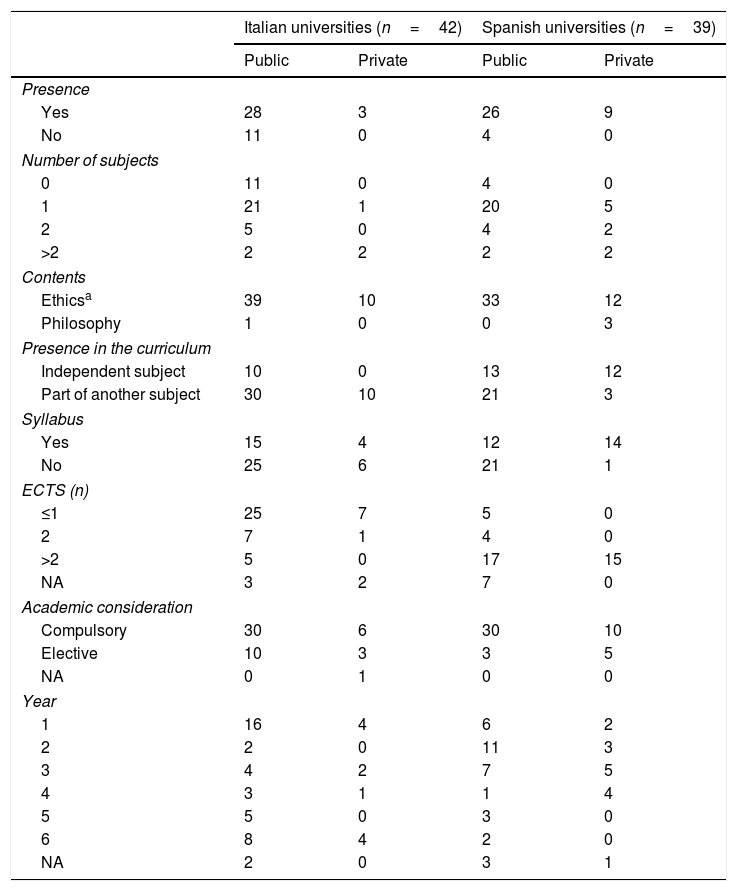

PhilosophySubjects on philosophy were offered mainly in the domain of ethics, with different names (Bioethics, Medical Ethics, Clinical Ethics, Clinical Bioethics, Medical Deontology and Professional Deontology). Most Italian (73.8%) and Spanish (83.3%) universities offered these courses, but differences were seen between private and public universities in both countries. All the private universities offered these courses whereas this was not the case for public universities (Table 3).

Characteristics of the subject Philosophy in Spanish and Italian Universities.

| Italian universities (n=42) | Spanish universities (n=39) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public | Private | Public | Private | |

| Presence | ||||

| Yes | 28 | 3 | 26 | 9 |

| No | 11 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Number of subjects | ||||

| 0 | 11 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| 1 | 21 | 1 | 20 | 5 |

| 2 | 5 | 0 | 4 | 2 |

| >2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Contents | ||||

| Ethicsa | 39 | 10 | 33 | 12 |

| Philosophy | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Presence in the curriculum | ||||

| Independent subject | 10 | 0 | 13 | 12 |

| Part of another subject | 30 | 10 | 21 | 3 |

| Syllabus | ||||

| Yes | 15 | 4 | 12 | 14 |

| No | 25 | 6 | 21 | 1 |

| ECTS (n) | ||||

| ≤1 | 25 | 7 | 5 | 0 |

| 2 | 7 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

| >2 | 5 | 0 | 17 | 15 |

| NA | 3 | 2 | 7 | 0 |

| Academic consideration | ||||

| Compulsory | 30 | 6 | 30 | 10 |

| Elective | 10 | 3 | 3 | 5 |

| NA | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Year | ||||

| 1 | 16 | 4 | 6 | 2 |

| 2 | 2 | 0 | 11 | 3 |

| 3 | 4 | 2 | 7 | 5 |

| 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| 5 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| 6 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 0 |

| NA | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

NA: not available.

Most universities offered only one subject in the curricula. In Spain, the subject was generally independent (94%), whereas in Italy, bioethics contents were commonly included in another subject (80%). Regarding ECTS credits, in Spain most subjects consisted of at least two credits and in Italy they consisted of one or less. In both countries, the subject that included bioethics was compulsory in most cases. Regarding the academic year, in Italy, some bioethics content can be found in every year with a maximum in the first (n=20) and sixth year (n=12). In Spain, the subjects were also offered in all academic years but the modes were in the second (n=14) and third year (n=12).

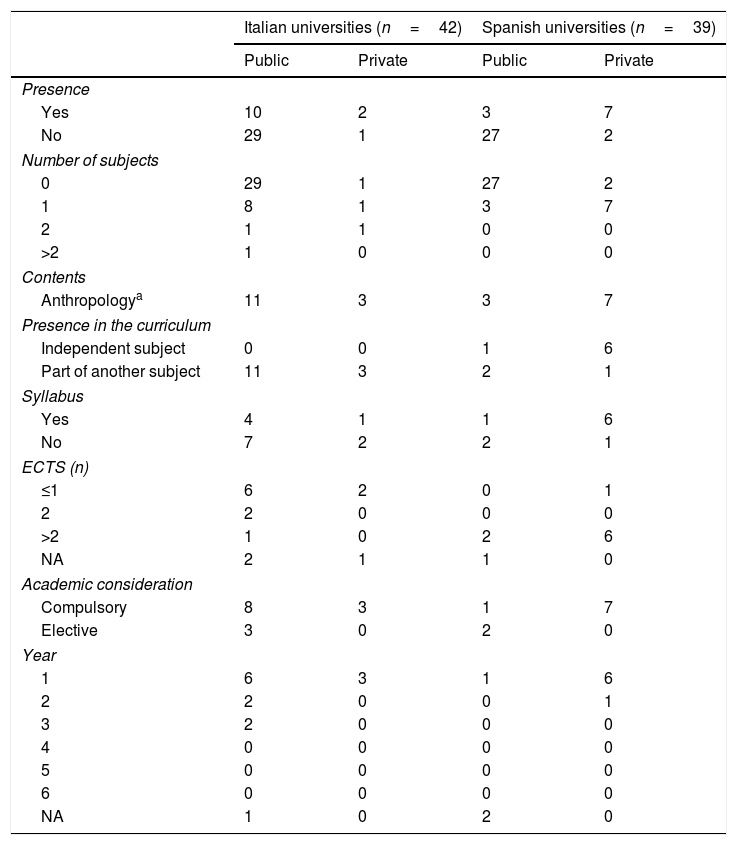

AnthropologyThe majority of Italian (n=30) and Spanish (n=29) universities did not offer this subject (Table 4). However, differences were seen between public and private universities, as most of the second group offered anthropology. In Italy, most universities only offered one course in the first year of the medical curriculum and, in all cases, as part of a general subject. The number of ECTS credits was of one or less for most subjects and the academic consideration was compulsory.

Characteristics of the subject Anthropology in Spanish and Italian Universities.

| Italian universities (n=42) | Spanish universities (n=39) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public | Private | Public | Private | |

| Presence | ||||

| Yes | 10 | 2 | 3 | 7 |

| No | 29 | 1 | 27 | 2 |

| Number of subjects | ||||

| 0 | 29 | 1 | 27 | 2 |

| 1 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 7 |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| >2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Contents | ||||

| Anthropologya | 11 | 3 | 3 | 7 |

| Presence in the curriculum | ||||

| Independent subject | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| Part of another subject | 11 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Syllabus | ||||

| Yes | 4 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| No | 7 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| ECTS (n) | ||||

| ≤1 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| >2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 6 |

| NA | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Academic consideration | ||||

| Compulsory | 8 | 3 | 1 | 7 |

| Elective | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Year | ||||

| 1 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 6 |

| 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| NA | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

NA: not available.

In Spain, anthropology courses were offered in only one subject in all cases. In most private universities, this subject was an independent course. In most universities, the number of ECTS credits was higher than 2 (n=8). The academic consideration was mostly compulsory (8 out 10) and offered in the first year of curriculum (7 out 10).

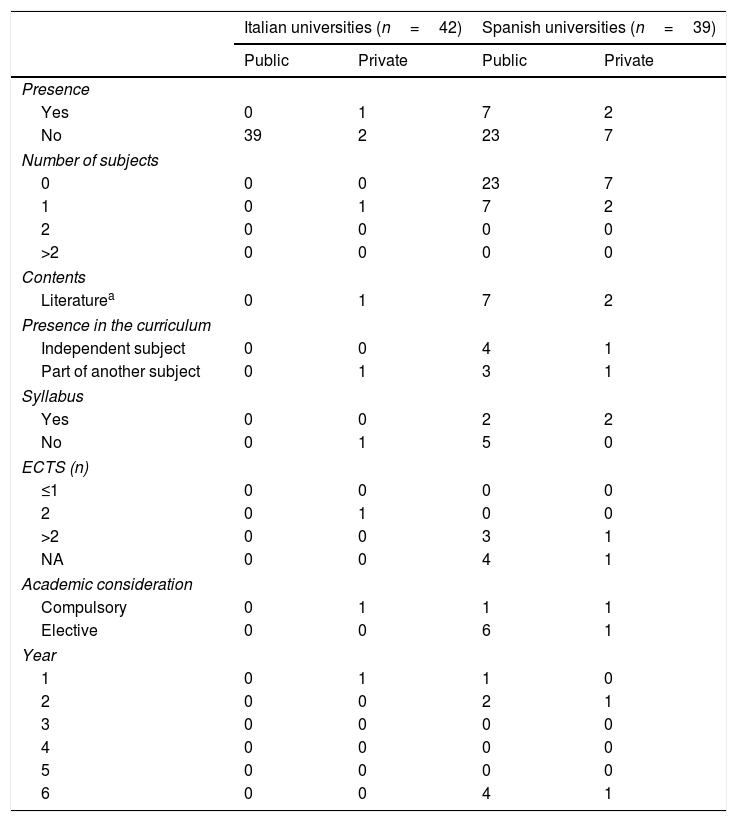

LiteratureThe Literature content was practically absent in Italian universities, where only one private university (Università Cattolica di Roma) offered a subject with content related to literature. In Spain, the subject was included in nine universities (Table 5). In five cases, the subjects were exclusively devoted to literature and the ECTS credits were at least two. In most cases (n=7), the subject was elective, and the year where it was offered unavailable.

Characteristics of the subject Literature in Spanish and Italian Universities.

| Italian universities (n=42) | Spanish universities (n=39) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public | Private | Public | Private | |

| Presence | ||||

| Yes | 0 | 1 | 7 | 2 |

| No | 39 | 2 | 23 | 7 |

| Number of subjects | ||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 23 | 7 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 2 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| >2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Contents | ||||

| Literaturea | 0 | 1 | 7 | 2 |

| Presence in the curriculum | ||||

| Independent subject | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 |

| Part of another subject | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Syllabus | ||||

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| No | 0 | 1 | 5 | 0 |

| ECTS (n) | ||||

| ≤1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| >2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| NA | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 |

| Academic consideration | ||||

| Compulsory | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Elective | 0 | 0 | 6 | 1 |

| Year | ||||

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 |

NA: not available.

The present study provides some important data that allows us to consider the academic situation of humanities in medical curricula of Italy and Spain in a quantitative manner. We will discuss the findings in two parts. First, we will consider the global data and after we will analyze the findings of the main subjects in detail.

One relevant finding refers to the fact that all the universities in both countries included at least one subject related to humanities in their curricula. Some important differences were observed among the type of subject and in a lesser degree, between the countries. In most universities, a subject on history of medicine and bioethics (under different names) was included. In the first case, almost all Italian universities had such a course, whereas in Spain the number was reduced to 85%. The opposite happened with bioethics, which was offered in almost all Spanish universities, but only in 73% of Italian ones. The third most frequent subject was anthropology with a reduced presence but similar in both countries. The fourth, literature, showed the most important difference in its presence in both countries.

These figures may be discussed in several ways. First, the existence of a history of medicine subject and a bioethics subject in most universities is positive. However, literature, cinema, visual arts or sociology were only present in a very small number of centers. This situation seems clearly insufficient to provide medical students with a broad understanding of the humanistic consideration of illness and sick people. This statement is reinforced by the academic characteristics of each subject.

Both subjects, history of medicine and bioethics, are clear paradigms of how these disciplines are treated in medical schools. In Italy, even though history of medicine is offered in almost all universities and is compulsory, its importance is very limited due to the fact that its contents are part of another subject and only one ECTS credit is allowed to be taught. This is clearly inadequate if the basis of the discipline is to be shown to students. The case of bioethics is very similar: it is offered in most universities but as part of another subject and without its own identity. This is a surprising fact because the importance of bioethics to developing professionalism in medical students is generally acknowledged as essential.16 History of medicine has been losing its importance in the training of medical students and this is an undesirable situation. The recovery of its old place as an important and separate subject for medical students seems to be a difficult issue in current times. Therefore, taking different actions has been suggested to promote the exposure of students to the critical contents of these subjects with strategies such as: the inclusion of history of medicine in faculty development programs, identifying members in medical schools interested in the subject or considering the introduction of contents related to the history of medicine in each major course.6 The strategy is, therefore, to blend the contents of history of medicine into a natural part of each course, not teach it as a separate course.

The most striking difference in the presence of humanities in both countries is the case of literature and language studies. This difference is again reinforced by the fact that a significant number of Spanish universities also offered subjects on religion, cinema or sociology, whereas the presence of such topics in the Italian counterparts is minimal or completely absent. In the case of religion, the explanation may be the existence of many Catholic private universities in Spain compared to Italy, but there is no reason to explain the absence of the other subjects. Perhaps Spanish universities are exploring the inclusion of these topics as part of a progressive change to follow the humanism movement. However, we can only speculate, as there is no data available to confirm this assumption.

Literature gives us a clear example of the educational opportunities of humanities in the training of medical students. As Hunter et al.17 pointed out, literature may strengthen and focus their training toward a better understanding of humane care of patients, but it is also a source of moral education. In recent years, the importance of literature has increased due to the recognition of the value of the narrative of patients,18 the use of literary texts as an adjuvant treatment of some diseases and the possibility to learn about specific experiences in medicine (aging, disability, death). The importance of literature in the training of medical students has been previously discussed and we refer interested readers to this paper.19 More recently, the importance of illness narratives as reported by patients has been outlined.20 But perhaps one of the strongest defences of the usefulness of literature in medicine comes from Shapiro et al.,21 who have recently written: “We suggest that literature is an essential element of medical education that, through the method of close reading, contributes intellectual inquiry, emotional awareness, socio-cultural context, and a countercultural perspective to questions regarding medical professionalism. Narrative and storytelling broaden and make more complex the ethical context of care provided by students and faculty […] Literature can deepen the understanding of medical professionalism as many educators desire.”

In conclusion, humanities are poorly included in the medical curricula of Italy and Spain. Even though history of medicine and bioethics are offered in almost all universities of both countries as a compulsory subject, the limited number of ECTS credits, especially in Italy, and their lack of consideration as independent subjects preclude its key role in the training of physicians. Additionally, the limited presence of other subjects, especially in Italy, is not good news for those who consider that humanities may clearly improve the understanding of what it really means to be a medical doctor. A review of the Italian literature published on medical humanities and healthcare education concluded that the situation was poor in Italy but comparable to other countries.2 They also asked for an increased effort in the planning of medical humanities courses and the need for further research to establish the situation of these subjects in undergraduate healthcare education in Italy. An interesting paper discussing the need for medical humanities and how to approach such a challenge in Spain has been recently published.10 Both may reflect a change of opinion on the subject and open new ways of considering their implementation in medical schools.

More than one century ago, Osler22 reminded us that physicians should “care more particularly for the individual patient than for the special features of the disease”. We would like to include a quote from Fitzgerald23 that summarizes how humanities will help medical students: “Scientific findings are information; knowledge is awareness of what can be done using this information; and wisdom is deciding whether or not to do it.”

Conflict of interestThe authors of this article declare no conflict of interest.