Innovation in medical teaching in recent years has undergone major changes. Traditionally, the teacher used to rely exclusively on words, the blackboard, and anatomical dissection. Nowadays, classes are supported by numerous tools with the help of the computer.

MethodsIn the Department of Human Anatomy of the Faculty of Medicine of our University, during the first 4-month period of the course, we introduced in the classes the projection of 13 short videos with an average duration of 2.33 min, from laparoscopic and open surgical interventions, endoscopic and radiological studies. We surveyed at the end of the first 4 months period to evaluate the student´s opinions of the videos shown.

ResultsRegarding the usefulness of the video projection, 82.8% considered the projection very useful and 17.2% considered them somewhat useful. None of the students considered the projection of the videos to be useless for their learning. As for the duration of the videos, 97.3% considered the duration to be adequate. In the survey, the students freely expressed diverse opinions. Among others, they stated that they help to understand the real anatomy of the structures studied in 3 dimensions and that they help to review and consolidate theoretical knowledge of what has already been explained. They also said that they help with motivation in preclinical subjects. Others felt that the videos help to raise awareness of the practical usefulness of the subject in the context of the practice of medicine.

ConclusionWe can assure that the projection of short prepared videos, taking sequences of open or laparoscopic surgical interventions and endoscopic or radiological studies, is very useful for improving the understanding of the subject of human anatomy, helping to clarify concepts and consolidating knowledge and increasing the student's motivation, as well as the performance in the study.

La innovación en la docencia médica en los últimos años ha sufrido grandes cambios. Tradicionalmente, el docente disponía exclusivamente de su palabra, de la pizarra y de la disección anatómica. Hoy en día las clases se apoyan numerosas herramientas con el apoyo del ordenador.

MetodosEn el departamento de Anatomía humana de la Facultad de Medicina de nuestra Universidad, durante el primer cuatrimestre del curso introdujimos en las clases la proyección de 13 videos cortos con una duración media de 2,33 minutos, procedentes de intervenciones quirúrgicas laparoscópicas y abiertas, estudios endoscópicos y radiológicos. Realizamos una encuesta al final del cuatrimestre evaluando la opinión de los alumnos sobre los videos proyectados.

ResultadosRespecto a la utilidad de la proyección de los videos, el 82,8% consideró muy útil la proyección y el 17,2% las consideró algo útiles. Ninguno de los alumnos consideró que la proyección de los videos fuera inútil para su aprendizaje. En cuanto a la duración de los videos al 97,3% les pareció que la duración era adecuada. En la encuesta los alumnos manifestaron libremente diversas opiniones. Entre otras, manifestaron que ayudan a comprender la anatomía real de las estructuras estudiadas en tres dimensiones y que ayudan a repasar y a asentar conocimientos teóricos de lo ya explicado. También que ayudan a la motivación con las asignaturas preclínicas. Otros opinaron que los videos ayudan a tomar conciencia de la utilidad práctica de la asignatura en el contexto del ejercicio de la medicina.

ConclusionPodemos asegurar que la proyección de videos cortos preparados, tomando secuencias de intervenciones quirúrgicas abiertas o laparoscópicas y de estudios endoscópicos o radiológicos, tiene una gran utilidad para la mejora de la comprensión de la asignatura de la anatomía humana, ayudando a aclarar conceptos y afianzar conocimientos e incrementando la motivación del alumno, así como el rendimiento en el estudio.

Innovation in medical teaching in recent years has undergone great changes. Traditionally, in the classroom, the teacher had only their word and the blackboard at their disposal, where they were supported by images painted directly with chalk, which required additional pictorial skill and time. On the other hand, human anatomy must necessarily be supported by dissection classes and the use of anatomical models, and this is done in most medical schools and faculties around the world. Nowadays, human anatomy theory classes are supported by projections and presentations with computer support. In recent years, numerous tools have emerged that complement the teaching of the subject by using 3D images created by computers and virtual reality.1,2

In the Department of Human Anatomy of the Faculty of Medicine of our university, we introduced the projection of short videos from surgical interventions, and endoscopic and radiological studies, to show anatomical areas of organs or specific structures as a complement to the theoretical class. The objective of these videos is that the student gets a general idea of the real human anatomy after the exposition and explanations of the theoretical foundations of human anatomy. Subsequently, we evaluate the impact on the students of this incorporation in the theoretical class.

The study aims to assess the opinion of the students of the Human Anatomy course of the second year of Medicine, on the projection at the end of the theoretical class, of prepared short videos, obtained from surgical interventions, clinical examinations, and radiological tests, to show the real human anatomy in the living human being.

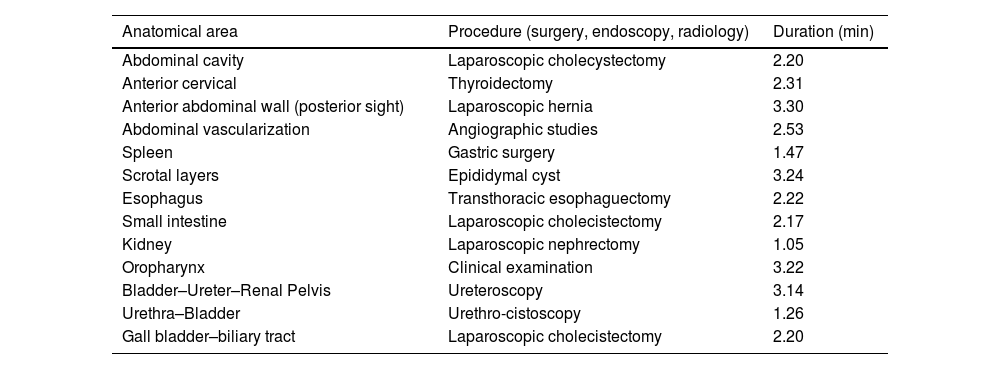

MethodsThe study was carried out by surveying 77 students (39.32%) out of a total of 196 that made up the total number of second-year medical students at our university during the first 4-month period of the academic year 2022–2023. During this period, we have developed a model to support the theoretical classes thanks to short videos of real anatomy obtained from real surgeries, mainly laparoscopic, but also open surgeries and endoscopic and radiological studies. In some of the classes, taught in the second-year human anatomy subject between September 2022 and December 2022, we projected at the end of the class a short video (in total 13) previously prepared, between 1.05 and 3.30 min (with an average duration of 2.33 min) as a support to the classes, coming from open surgeries, laparoscopic surgeries, urological endoscopic explorations, and samples of some radiological explorations such as MRI, angio-CT, arteriography, or lymphography (Table 1). Only students who were shown the videos were surveyed.

Videos used to support the teaching of human anatomy.

| Anatomical area | Procedure (surgery, endoscopy, radiology) | Duration (min) |

|---|---|---|

| Abdominal cavity | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy | 2.20 |

| Anterior cervical | Thyroidectomy | 2.31 |

| Anterior abdominal wall (posterior sight) | Laparoscopic hernia | 3.30 |

| Abdominal vascularization | Angiographic studies | 2.53 |

| Spleen | Gastric surgery | 1.47 |

| Scrotal layers | Epididymal cyst | 3.24 |

| Esophagus | Transthoracic esophaguectomy | 2.22 |

| Small intestine | Laparoscopic cholecistectomy | 2.17 |

| Kidney | Laparoscopic nephrectomy | 1.05 |

| Oropharynx | Clinical examination | 3.22 |

| Bladder–Ureter–Renal Pelvis | Ureteroscopy | 3.14 |

| Urethra–Bladder | Urethro-cistoscopy | 1.26 |

| Gall bladder–biliary tract | Laparoscopic cholecistectomy | 2.20 |

Before the recording of the video and the performance of the surgical or endoscopic procedure, the patient signs an informed consent form authorizing the recording of videos for teaching purposes. We elaborate on videos from abdominal surgical interventions, both open and laparoscopic. We also used videos from urethral-cystoscopies, ureteroscopies, and radiological studies. The videos were prepared by editing the original recording using a video editor (iMovie-Apple ©) including a presentation with a title, eliminating the parts related to the surgical technique and focusing mainly on the images of the anatomical structures. Other video segments of no interest to the subject matter were also eliminated. Reviews of the structures to be highlighted were included and some video segments of special interest were slowed down, as also described by Kumar in the description of his projection.3 At the abdominal and pelvic level, only those parts focused on the visualization of the peritoneal anatomy and abdominal organs were shown, as well as those anatomical details present in the lumen of the urinary tract and gastrointestinal tract. At the oropharyngeal and cervical level, areas of interest related to the previously explained subject were shown. The video was stopped due to the need for a concrete explanation.

The videos projected were to show the actual anatomy of the following areas, organs or apparatus: Anatomy of the renal pelvis, intraluminal ureter and bladder from a uretero-cystoscopy, intraluminal urethral anatomy and its portions from a urethroscopy, anatomy of the scrotal layers from epididymal cyst surgery, anatomy of the renal surface and vascularization of the kidney from a laparoscopic nephrectomy, anatomy of the oropharynx from clinical oropharyngeal explorations, anatomy of the anterior cervical region from a thyroidectomy, esophageal anatomy from an esophagectomy in its thoracoscopic time, general anatomy of the abdominal cavity from laparoscopic abdominal surgery, anatomy of the anterior abdominal wall (posterior sight) from laparoscopic inguinal hernia surgery, surface anatomy of the spleen from laparoscopic gastric surgery, anatomy of the small bowel from laparoscopic abdominal surgery, anatomy of the extrahepatic bile duct and gallbladder from laparoscopic cholecystectomy, and the vascularization of abdominal organs from radiological samples of angio-CTs, MRI, and dynamic angiography of the abdominal vasculature (Table 1).

The group to which the videos were shown was surveyed at the end of the term to evaluate, among other issues, the student´s opinions about the videos shown. A total of 77 students responded. Numerous questions were asked regarding the student´s opinion on the structure of the class, the student's attitude in the classroom, or how the students thought the class could be improved. Among other questions, students were asked about their opinion regarding the projection of anatomical videos at the end of the classes during the previous term. They were also asked if the duration of the videos seemed adequate and if they thought that other audio-visual aids could be useful as support for the classes. Regarding the usefulness of the videos projected in the anatomy class, the students were offered 4 response options: very useful, somewhat useful, useless, or an option where the student could express that the video produced confusion regarding the learning of anatomy. Regarding the length of the videos, students were asked if they considered them adequate or inadequate.

ResultsRegarding the usefulness of video projection, 82.8% of the 77 respondents considered very useful the projection of video fragments corresponding to the anatomical exposition from open or laparoscopic surgical procedures or endoscopic and radiological studies. The 17.2% considered them somewhat useful. None of the students considered the projection of the videos to be useless for their learning or expressed that it confused or hindered them in their learning. As for the duration of the videos, 97.3% felt that the duration was adequate, while only 2.7% expressed that they did not feel it was adequate. 57.3% considered that incorporating other audio-visual media in anatomy classes could be beneficial for the learning of the subject while 42.7% did not think that it provided an additional benefit to the theoretical classes.

In the survey, the students freely expressed diverse opinions regarding the support of the human anatomy classes with videos of open or laparoscopic surgical procedures, endoscopies, or radiological studies. The opinions regarding the videos were varied, but in general, most of them considered that the videos were very useful for understanding the subject matter. Among others, the most frequently expressed opinions were that they help to understand the real anatomy of the structures studied in 3 dimensions and that they help to review and consolidate theoretical knowledge of what has already been explained. Several of them stated that they help motivation mainly in the first years with preclinical subjects. Others felt that the videos help to raise awareness of the practical usefulness of the subject in the context of the practice of medicine. And finally, many students felt that the videos were the best and most useful part of the anatomy classes.

DiscussionAnatomy should be the cornerstone of medical education. As human anatomy is one of the first subjects that bring the student into contact with medicine, it is often the first impression of medical activity.

The application of different methods of teaching human anatomy continues to be debated today. Since the Middle Ages, the teaching of anatomy was built on master classes based on the knowledge of classical anatomists, many of them based on comparative anatomy with animals.4 Later on, anatomical dissection was introduced in its different modalities of prosection and guided dissection, already allowed by the civil and ecclesiastical authorities.4,5 Already in the Renaissance, Andreas Vesalius, after publishing "De humani corporis fabrica", established a guide for the learning of human anatomy that would be used for more than 300 years.6

Human anatomy has traditionally represented a subject with an important teaching load in the first years of the medical career. In recent years, the number of teaching hours has been significantly reduced (from 500 to 50 h depending on some cases).1 This, according to some authors, undoubtedly leads to an increase in morbidity and mortality in medical procedures due to the lack of knowledge of the different anatomical structures.7 Residents learn anatomy from patients, which is not the ideal situation. Many postgraduates consider their knowledge of human anatomy to be insufficient, and some feel that they need a refresher course.8 In some curricula, as a tool to improve the teaching of some preclinical subjects, including anatomy, the integration of basic sciences, including human anatomy, with clinical medicine has been proposed.5 The implementation of applied clinical anatomy in the classroom has increased critical thinking, interest in learning anatomy, and surgical learning and training. Usually, the supervision of this learning environment in the teaching of human anatomy has been performed by surgeons. Applied clinical anatomy involves a greater emphasis on anatomical details of clinical importance, thus the interest it represents lies in how knowledge of human anatomy affects clinical practice.9 Supplementing traditional anatomy teaching with elements of applied clinical anatomy has a very positive impact on anatomical knowledge. In a survey of students studying at centers with applied clinical anatomy implementation, 96% of respondents felt that these modifications had a very positive impact on the teaching of human anatomy. The principles of applied clinical anatomy can be implemented without great resources or effort.9

Until recently, human anatomy classes have relied on the use of images, with the use of 2-dimensional plates and projections, plastic models, dissection, and prosection classes in cadavers and later 3D projections. In recent years, it has also been supported by multimedia, computer, and virtual reality.1,2,10,11 The coronavirus pandemic led to the need to improve classroom support with various teaching tools such as video conferences and new digital technologies. In addition, a great effort was made to replace the part of practical education based on anatomical dissection with educational dissection videos. Numerous formats have been used to make edited anatomical videos available to students, such as through the university platform,12 or public platforms such as YouTube.13,14 We decided to show the video at the end of the theoretical class.

Real anatomical structures show significant differences concerning slides, computer simulations in both 2D and 3D, or even cadavers for volume and coloration. Although the dissection room provides a real view of the anatomy of the cadaver, the cadaver does not represent the anatomical reality of the living human being. All the means traditionally used in the teaching of anatomy have been and are useful for the localization and identification of anatomical structures,1,2 however, there are physicians, especially those who have performed non-surgical specialties, who, after their training period, have never seen much of the real anatomy of the human body unless they have done it in surgical practices. For this reason, some specialists, mainly in medical specialties, find it particularly difficult to understand certain particular aspects of human anatomy. The teaching of human anatomy has very rarely relied on media that show the real anatomy of living people. The purpose of the projection of videos from real interventions and explorations is to show a very close approximation to the anatomical reality of the human being, which represents a novelty in recent years in the teaching of human anatomy. The use of live subjects has been described previously, especially for the teaching of surface anatomy where the students themselves can participate as the object of this learning.15 Laparoscopy has been used for cadaveric teaching of human anatomy to avoid the anatomical distortion of opening the abdomen completely.16 Kumar et al used videotaping of laparoscopic cholecystectomy as an adjunct to teaching abdominal anatomy. Cadaver laparoscopy has been used for teaching purposes and nowadays, it is a widely used tool for surgical technique courses.3,16 Videos of arthroscopy recordings have also been used as an aid to the understanding of joint anatomy.17 In our department, we propose the projection of very short videos showing the real anatomy of the human body during open and laparoscopic surgery, as well as endoscopic studies of the urinary and digestive tract and radiological studies, avoiding the pathological aspects of the operated patient and showing only anatomical elements of interest for the class to be explained that day. We believe that the anatomy visualized in some surgical interventions can have an important role in supporting the teaching of human anatomy. There is little history of the use of video projection to support the teaching of human anatomy. We have edited the videos to show exclusively the anatomical details of interest as well as to adjust the duration of the projection. In this sense, there are other antecedents in the bibliography that support the previous preparation of the video. Several studies support the incorporation of dissection videos into the educational material permanently and their incorporation into the classes. The originality of our proposal lies in the fact that they are live patient videos and in their brevity. The positive opinion of our students on the projected video format as well as its duration far exceeded that of other similar studies. Moreover, the effectiveness of these videos is much higher when they have been edited and produced by experts.12,13,18

As for the duration of the videos, the average duration of our series was 2.33 min. We proposed a very short duration to maintain maximum attention to the videos. When we designed the videos, we thought first of all that their duration should be very short because their projection is done at the end of the class, a moment in which the student's concentration is already quite diminished and at the same time serves as a change with concerning the attention that the theoretical class requires. The videos are complementary to the class and their rationale is to improve comprehension, clarify, and consolidate knowledge and review what has been explained, as attested to by numerous students in the statements freely expressed at the end of the survey.

Other authors have proposed videos of longer duration. Toping, uses cadaver dissection videos ranging from 11 to 50 min. The videos were used as an adjunct to lecture teaching because of the shortened anatomy hours.19 This format does not allow their incorporation as a complementary tool to the classes. Given the reduction of teaching hours in the subject of anatomy in recent years, it is necessary to adjust very carefully the time devoted to each explanation.1 In other similar initiatives with video projection, longer durations have been considered excessive by some students as they required too much time for viewing.18,19 The video used by Kumar, at the University of Oman, was 30 min long,3 which would imply taking up a large part of the class for the projection of the video. Our interest was the use of videos as a complement to the previous explanation, which is why their use if they were to occupy a large part of the lecture class, would have further reduced the knowledge to be explained during class time. On the internet and specifically on platforms such as YouTube, there are numerous support pages for teaching disciplines outside of human anatomy such as embryology and histology with very good results.13 On the other hand, there are numerous pages of human anatomy where the student can find classes and videos of anatomical dissection.14 Most of these videos are of anatomical dissection and of long duration where the objective is to teach an anatomy or anatomical prosection class. Our videos are intended to clarify, reinforce, and show in a reliable way what was explained in the same class and not to teach a new class. The current academic context makes it necessary to update the tools available to the teacher and one of them is the prepared videos. Given the characteristics of the new generations formed in an environment where audio-visual media, social networks, or simply cell phones abound, distractions during class or study often make the success of the learning process more difficult.20,21 Given this evidence, we think that the projection of longer videos at the end of a class could make it difficult to maintain attention to the video shown. The fact that 97.3% of the students thought that the duration of the videos was adequate indicates that short videos with brief and direct information have a greater impact and more acceptance in the current generations. On the other hand, regardless of the duration, the videos have been modified, highlighting moments of interest in the projection or slowing down specific areas as also described by Kumar in his description of his projection.3

Another aspect to consider in this initiative is motivation. Those factors that increase motivation for study play an important role during the academic formative years and we must give them a significant role. Stimulating motivation is an incentive to study, improves academic results, and opens the way for research in all areas of knowledge.22 We propose the projection of these videos also as a motivational element for students. In the initial years of medical school, many students are demotivated due to the delay in immersion in clinical practice. Even a not insignificant percentage of students drop-out of their studies due to this fact.23 The incorporation of clinical information or information on diagnostic and therapeutic means in the first years of the degree represents a motivating impulse to continue their studies.5,9 The majority of students in the survey endorsed the important motivational role of these videos, as they have done in other similar initiatives.3 There was also unanimity among the students regarding the usefulness of the projection of videos of surgical interventions as a support for the theoretical class, which should make us think about looking for more tools to support the theoretical classes given the change of paradigm in recent years.

ConclusionIn conclusion, we can assure that the projection of short prepared videos, taking sequences of open or laparoscopic surgical interventions and endoscopic or radiological studies, has a great utility for the improvement of the understanding of the subject of human anatomy, helping to clarify concepts and consolidate knowledge and increasing the motivation of the student, as well as the performance in the study.