The main objective of this study was to verify the association of perceived stress with anxiety, sleep quality, and academic performance among Moroccan medical students.

MethodsThis cross-sectional study included 222 students enrolled at the Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy of Fez in Morocco. An online self-administrated questionnaire, for the sociodemographic characteristics, Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10), Test Anxiety Scale, and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index questionnaire were used for the assessment. A descriptive and correlational design was used in this investigation.

ResultsOne hundred and thirty-two students completed the survey. A high level of stress was found. A significant positive correlation was observed between the stress level among our population and their levels of anxiety. Stress was also positively correlated with the decrease of students’ sleep quality and academic performance.

ConclusionThe results of this investigation present worthy data that highlight the need for this subset of students to anti-stress programs that must be integrated into their curriculum to help them to better manage this psychological issue.

El principal objetivo de este estudio fue verificar la asociación del estrés percibido con la ansiedad, la calidad del sueño y el rendimiento académico entre estudiantes de medicina marroquíes.

MétodosEste estudio transversal incluyó a 222 estudiantes matriculados en la Facultad de Medicina y Farmacia de Fez en Marruecos. Para la evaluación se utilizó un cuestionario autoadministrado en línea para las características sociodemográficas, la Escala de estrés percibido (PSS-10), la Escala de ansiedad ante los exámenes y el cuestionario del Índice de calidad del sueño de Pittsburgh. En esta investigación se utilizó un diseño descriptivo y correlacional.

ResultadosCiento treinta y dos estudiantes completaron la encuesta. Se encontró un alto nivel de estrés. Hubo una correlación positiva significativa entre los niveles de estrés y ansiedad. El estrés también se correlacionó positivamente con la disminución de la calidad del sueño y el rendimiento académico de los estudiantes.

ConclusiónLos resultados de esta investigación presentan datos valiosos que resaltan la necesidad de que este subconjunto de estudiantes reciba programas antiestrés que deben integrarse en su plan de estudios para ayudarlos a gestionar mejor este problema psicológico.

The medical profession is inherently stressful. In parallel, physicians report a high level of stress and burnout.1 This high prevalence is mirrored in the literature among medical students, underling the need for the integration of a multiple anti-stress process into the medical curriculum. Such integration requires a deep understanding of potential stressors and impact of stress within this population. Actually, it was widely reported that medical students are facing with supplemental stressors such as being in perpetual contact with patients and performing clinical work. These stressors could generate psychological issues for students if they are coped with maladaptive strategies. In light of this, it will be not surprising that, when asked, medical students rate their time in medical school as stressful,2 with dissatisfaction with academic performance, examinations, and fear of failing as commonly cited reasons for their stress.3

The impacts of chronic stress on medical students are preponderant; the decrease of academic achievement,4 and poor sleep quality.5 In addition, damaging consequences on students’ physical and psychological health6 have been reported.

Several studies have investigated the relationship between psychological stress and academic achievements.7 Kötter et al. (2017) reported that academic performance7 is predicted by students’ age and gender, making older female students with high stress scores a potential risk group for the vicious circle of stress and poor academic performance. Adams et al.8 investigated the correlations between several students’ characteristics and academic integration, the findings illustrating that perceived stress mediates students’ integration. Moreover, Sohail et al.9 examined the association between stress and academic performance, and the results showed a significant correlation between stress level and poor academic performance.

It has been widely reported that medical students typically suffer from sleep deprivation or poor sleep quality more than their non-medical students' peers.10 The decrease in sleep quality was specially related to students’ psychological problems including stress.5 Almojali et al. (2017) reported the high prevalence of stress and poor sleep quality among Saudi medical students, with a statistically significant association between these 2 variables.11 Furthermore, this investigation indicated that students who are not suffering from stress are more likely to have poor sleep quality. In the same way, Rebello et al. (2018) reported the positive correlation between high levels of perceived stress and poor sleep quality among Indian medical students.2 Moreover, a study investigating a multilevel analysis exploring the link between stress and sleep problems showed that perceived stress is an element determining element variable of stress quality.

Previous studies have shown that medical students often experience significant anxiety, as indicated by notable rates such as 54.5%, reported by Yusoff et al.,12 and 64.3%, reported by Wahed et al.13 This psychological challenge is commonly linked to perceived stress. Shamsuddin highlights a positive correlation between stress and anxiety symptoms among Indian university students. Additionally, the outcomes of this research support the link between stress and anxiety among Malaysian university students.14

Even though the association of stress with some psychological and academic impacts among medical students has been widely discussed at the international level, these types of measures have not to be investigated in the Moroccan context. The picture of the need to investigate the correlation between stress and its impacts among Moroccan medical students during their academic curriculum is considered of vital importance to support this subset of students. Therefore, the main objective of this study was to assess the correlation between psychological stress and sleep quality, anxiety, and academic performance.

MethodsSampleIn the period between November–December 2017, first-year to fifth-year medical students enrolled at the Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy of Fez-Morocco were invited to take part in an online study looking at stress and its impacts. The average time required for participants to answer the questionnaire was around 15 min. To prevent an overestimation of stress levels among students, we scheduled our study a month before the final exams. All students were invited through the faculty’ website and printed posters were placed in several areas around the faculty’ campus. The advertisements included brief information about the study, the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the questionnaire’s link published on the faculty’s website, and potential contact information about the project as well as the mailing address of the project, and contact persons. Prospective participants who expressed their interest in the survey got access to the questionnaire’s link.

Sample size and sample techniqueThe sample size was estimated by assuming the following factors: confidence interval, 95%; margin error, 5%; and the prevalence of perceived stress among Moroccan students was 17.17%.15 The following equation was used, where z is the Z-score=1.96, ε is the margin of error=0.05 and p is the prevalence=0.171: n=z2×p1−pε2.

Using this formula, the estimated sample size was 217. Basing on these results, a sample size of 222 of Moroccan medical students was used for this study.

Inclusion and exclusion criteriaFirst-year to fifth-year Medical students enrolled at Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy of Fez were included in the study. Exclusion criteria: Students reporting having psychiatric disorder were excluded from the study.

MaterialsThe survey was comprised of the following:

- •

Sociodemographic questions (age, gender, study’ cycle…). The study cycle was subdivided into 2 sections including the pre-clinical cycle (first or the second year of study) and the clinical cycle (third, fourth, or fifth year of study).

- •

Several validated questionnaires assessed aspects of perceived stress, anxiety sleep quality, and academic performance as detailed below.

A French validated version of the Perceived Stress Scale with 10 items (PSS-10)16 was used to examine students’ stress levels. The questionnaire requires participants to assess their stress by indicating how often over the last month they have felt a particular situation using 5-Likert (0—never to 5—all the time). Higher scores reflected an increased perceived psychological stress.

Anxiety symptomsStudents’ anxiety symptoms were assessed using the Test Anxiety questionnaire. Test Anxiety is an adapted version of the Test-Anxiety Inventory questionnaire.17 The Test Anxiety Scale is a 10-item instrument with a 5-point scale items ask about worry and dread, which interfere with concentration, and self-assessed performance impairment related to anxiety.17

Sleep qualityPittsburgh Sleep Quality Index scale (PSQI)18 was used to measure students’ sleep quality during the previous month. The scale consists of 7 domains (19 items) self-rated questions evaluating usual sleep habits during the last month. The possible scores range from 0 to 21, with greater than 5 indicative of impaired sleep quality.

Academic performanceThe academic performance of students was assessed using Study Management and Academic Results Test scale (SMART). SMART scale comprised 19 questions measuring study-related cognitions, time management, and study habits among students.19 Each question is based on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”.

Participants were required to answer mandatory questions covering essential sociodemographic information, stress levels, anxiety, and sleep quality scales. Additionally, there were optional questions, such as those inquiring about the presence of family in the living city or potential conflicts with their family.

Data analysisStatistical analysis were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21.0. Student’s unpaired t-test and Pearson’s chi-square test were applied to compare subgroups. The Spearman’s rank correlation test was used to examine the correlation between the PSS-10 score and the scores for Anxiety-test, SMART, and PSQI. The normality of the quantitative variables was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. A p-value ≤.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

Ethical considerationsFollowing the local legislation, ethical as well as scientific approval for the protocol of the study was obtained from the University Hospital Centre Hassan II of Fez, Morocco.

Analytic strategySPSS software for Windows version 21.0 was used for the statistical analyses. The prevalence of psychological stress was calculated with a 95% confidence interval (CI). The association between psychological stress and its potential impact factors was determined with Univariate analysis using Pearson’s chi-square test for categorical variables and the Pearson test was used to analyze correlations. p-value <.05 was considered statistically significant.

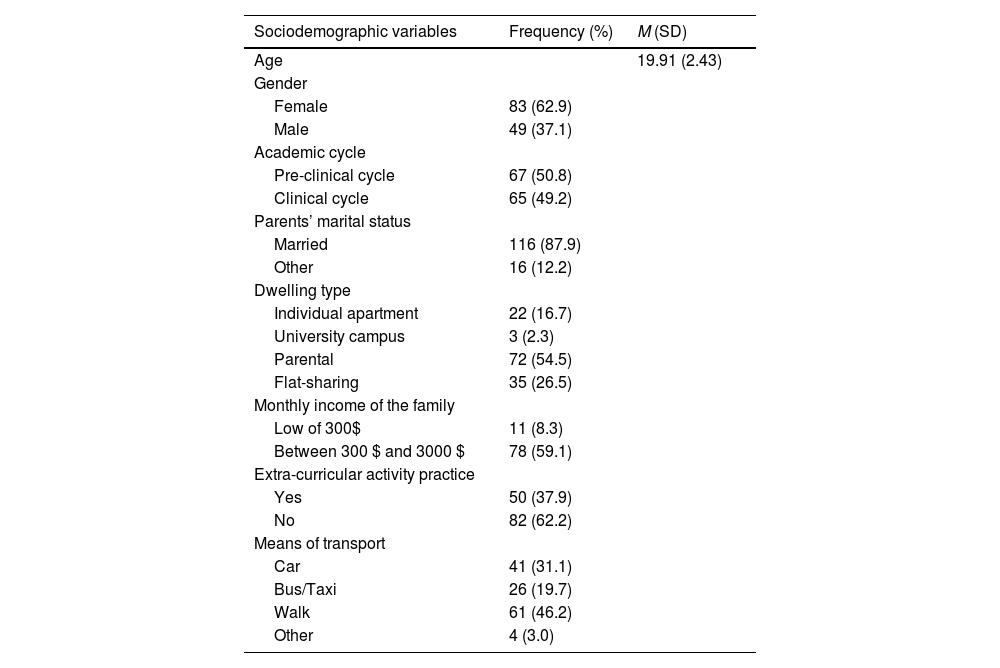

ResultsSociodemographic characteristics of the study sampleAmong the invited students, 222 (n=222) co-operated in this study. After the elimination of the uncompleted responses, 132 students were included in the study of which 37.1% (n=49) were male and 62.9% (n=83) were female. The mean age was 19.92 (SD=2.43) years. According to the results of the survey, 62.2% (n=82) did not exercise any type of extra-curricular activity, and 54.5% of them declared living in a family apartment. The majority of our population falls within the middle social class (59.1%) and have reported walking to get to the university (46.2%). Table 1 shows the detailed sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study sample (n=132).

| Sociodemographic variables | Frequency (%) | M (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 19.91 (2.43) | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 83 (62.9) | |

| Male | 49 (37.1) | |

| Academic cycle | ||

| Pre-clinical cycle | 67 (50.8) | |

| Clinical cycle | 65 (49.2) | |

| Parents’ marital status | ||

| Married | 116 (87.9) | |

| Other | 16 (12.2) | |

| Dwelling type | ||

| Individual apartment | 22 (16.7) | |

| University campus | 3 (2.3) | |

| Parental | 72 (54.5) | |

| Flat-sharing | 35 (26.5) | |

| Monthly income of the family | ||

| Low of 300$ | 11 (8.3) | |

| Between 300 $ and 3000 $ | 78 (59.1) | |

| Extra-curricular activity practice | ||

| Yes | 50 (37.9) | |

| No | 82 (62.2) | |

| Means of transport | ||

| Car | 41 (31.1) | |

| Bus/Taxi | 26 (19.7) | |

| Walk | 61 (46.2) | |

| Other | 4 (3.0) | |

All data were expressed as mean±SD, or percentage, as appropriate.

In univariate analysis, no gender differences in sociodemographic characteristics were found in our study sample except for monthly family incomes (p=.014), in which females constitute the majority within the middle economic range (Table 2).

Gender differences in sociodemographic characteristics.

| Sociodemographic variables | Students’ gender | p-value | OD (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | |||

| Age; M (SD) | 20.74 (3.11) | 19.63 (2.09) | .062 | [−2.261, 0.056] |

| Academic cycle | ||||

| Pre-clinical cycle | 14 (20.9) | 53 (79.1) | .195 | [0.764, 3.708] |

| Clinical cycle | 20 (30.8) | 45 (69.2) | ||

| Parents’ marital status | ||||

| Married | 27 (23.3) | 89 (76.7) | .079 | [0.133, 1.146] |

| Other | 7 (43.8) | 9 (56.3) | ||

| Dwelling type | ||||

| Individual apartment | 6 (27.3) | 16 (72.7) | .711 | – |

| University campus | 0 (0.0) | 3 (100) | ||

| Parental | 20 (27.8) | 20 (27.8) | ||

| Flat-sharing | 8 (22.9) | 8 (27.8) | ||

| Monthly income of the family | ||||

| Less than 300$ | 6 (54.5) | 5 (45.5) | .014* | [1.257, 17.197] |

| Between 300 $ and 3000 $ | 16 (20.5) | 62 (79.5) | ||

| Extra-curricular activity practice | ||||

| Yes | 17 (34.0) | 33 (66.0) | .091 | [0.892, 4.349] |

| No | 17 (20.7) | 65 (79.3) | ||

| Means of transport | ||||

| Car | 6 (14.6) | 35 (85.4) | .054 | – |

| Bus/Taxi | 11 (42.3) | 15 (57.7) | ||

| Walk | 15 (24.6) | 46 (75.4) | ||

| Other | 2 (50.0) | 2 (50.0) | ||

p-values were calculated using Pearson’s chi-square test for categorical variables and Student’s t-test for quantitative varibales.* Significant p-value (<.05).

Perceived stress was assessed using the PSS-10 scale. Some scores were reverse coded before the sum scores being calculated. Respondents who scored 20 or above were deemed as experiencing “high stress” levels. Using this criterion, 11.4% (n=15) of respondents reporting a “high stress” level and 51.5% (n=68) of them had moderate stress levels. Adopting a multicategorical approach, it was established that 37.1% of students (n=49) experienced “normal” or “low” stress level (non-stressed), whereas 62.9% (n=83) of our study participants exhibited stress level ranging from “moderate” to “high” (stressed). More details are given in Table 3.

Perceived stress prevalence.

| PSS-10 score | 0–10 | 11–20 | 21–30 | 31–40 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interpretation of stress score | Low | Normal | Moderate | High |

| Pre-clinical cycle, n (%) | 3 (2.3) | 21 (15.9) | 34 (25.8) | 9 (6.8) |

| Clinical cycle, n (%) | 0 (0) | 25 (18.9) | 34 (25.8) | 6 (4.5) |

| Total, n (%) | 3 (2.3) | 46(34.8) | 68 (51.5) | 15 (11.4) |

| Stress status, n (%) | Non-stressed, 49 (37.1) | Stressed, 83 (62.9) | ||

The mean (SD) PSQI score was 7.03 (3.31) proving that the average of medical students have a poor sleep quality (PSQI score≥“5”). Of the 7 components of the PSQI scale, the mean scores of subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep disturbance, and daytime dysfunction were above ‘1,’ making them the highest contributing subscales to the global PSQI score. However, habitual sleep efficiency and use of sleep medication had mean scores below “1”. The correlations between the PSS-10 score and the scores of the 7 components of the PSQI scale are outlined in Table 4. The analysis reveals a significant and notably positive correlation between perceived stress and the total sleep quality score (r=0.41; p=.01), indicating that stressed students are more likely to have lower sleep quality. In addition, an examination of the correlation between perceived stress and various components of the PSQI scale highlights positive associations with 6 specific components. These components include subjective sleep quality (r=0.44; p=.01), sleep latency (r=0.26; p=.05), sleep duration (r=0.26; p=.05), usage of sleep medication (r=0.233; p=.05), and daytime dysfunction (r=0.434; p=.01).

Correlation between Perceived Stress Scale-10 score and scores of components of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index among the participants, n=132.

| PSQI components | Total (mean±SD) | Stress subgroups | Pearson’s rank correlation coefficient (r) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n=83), (mean± SD) | No (n=49), (mean±SD) | |||

| Global PSQI score | 7.03±3.31 | 5.38±2.39 | 7.94±3.40 | 0.41⁎⁎ |

| Subjective sleep quality | 1.41±0.79 | 1.67±0.75 | 0.92±0.62 | 0.44⁎⁎ |

| Sleep latency | 1.23±0.94 | 1.47±0.94 | 0.82±0.79 | 0.26⁎ |

| Sleep duration | 1.33±0.92 | 1.45±0.91 | 1.06±0.89 | 0.21⁎ |

| Habitual sleep efficiency | 0.61±1.05 | 0.50±0.91 | 0.80±1.24 | −0.62 |

| Sleep disturbance | 1.00±0.72 | 1.06±0.74 | 0.90±0.66 | 0.92 |

| Usage of sleep medication | 0.24±0.72 | 0.32±0.81 | 0.10±0.49 | 0.233⁎ |

| Daytime dysfunction | 1.59±0.96 | 1.85±0.97 | 1.13±0.75 | 0.434⁎⁎ |

The average score of Anxiety Test was 2.82 (SD=1.09). High to extremely high anxiety level was found among 31.8% of our population. Table 5 shows the correlations between PSS-10 scores and Test Anxiety score. The results of these measures highlighted the high positive correlation between perceived stress and the global anxiety score (r=0.404; p=.01). Furthermore, stressed students seem to have anxiety symptoms since 45.8% of them (n=38) had a high to extremely high-stress level. However, only 8.2% of non-stressed students (n=4) had this psychosomatic problem.

Correlation between Perceived Stress Scale-10 score and Test Anxiety scale.

| Test anxiety scores | Test anxiety interpretation | Study group, n=132 | Stress subgroups | Pearson’s rank correlation coefficient (r) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stressed (n=83), (mean±SD) | Non-stressed (n=49), (mean±SD) | ||||

| 1–1.9, n (%) | Comfortably low anxiety level | 21 (15.9) | 5 (6.0) | 16 (32.7) | |

| 2–2.5, n (%) | Normal to moderate anxiety level | 18 (13.6) | 6 (7.2) | 12 (24.5) | |

| 2.6–2.9, n (%) | Normal to high anxiety level | 26 (19.7) | 16 (19.3) | 10 (20.4) | |

| 3–3.4, n (%) | Moderately high anxiety level | 19 (14.4) | 13 (15.7) | 6 (12.2) | |

| 3.5–3.9, n (%) | High anxiety level | 25 (18.9) | 21 (25.3) | 4 (8.2) | |

| 4–4.9, n (%) | Extremely high anxiety level | 17 (12.9) | 17 (20.5) | 0 (0) | |

| Global test anxiety score (mean±SD) | 2.82±1.09 | 3.13±1.12 | 2.3±0.82 | 0.404⁎⁎ | |

Table 6 shows a significant negative correlation between perceived stress scores and the 4 components of SMART scale including academic skills (r=−0.278; p=.01), skills test (r=−0.501; p=.01), stress management (r=−0.364; p=364), and strategic studying (r=−0.315; p=.01).

Correlation between perceived stress and different components of SMART scale.

| SMART components | Total (mean±SD) | Stress subgroups | Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (r) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n=83), (mean±SD) | No (n=49), (mean±SD) | |||

| Academic skills | 3.33±0.73 | 3.23±0.78 | 3.50±0.63 | −0.278⁎⁎ |

| Skills test | 2.373±0.72 | 2.103±0.64 | 2.803±0.65 | −0.501⁎⁎ |

| Stress management | 2.06±0.5 | 1.88±0.5 | 2.35±0.56 | −0.364⁎⁎ |

| Strategic studying | 3.21±0.68 | 3.03±0.70 | 3.46±0.59 | −0.315⁎⁎ |

Various independent t-tests were conducted to compare differences in total PSS, test anxiety, SMART test, and PSQI scores, as well as established categories of perceived stress, anxiety, academic performance, and sleep quality levels between males and females. Overall, no gender differences were observed in our study population for the 3 psychological determinants, including perceived stress (p=.469), anxiety (p=.335), and sleep quality (p=.858). The same results were observed for the 4 scores of the SMART sub-scales, including academic skills (p=.606), skills test (p=.064), stress management (p=.996), and strategic studying (p=.898), proving the absence of gender differences for the academic performance determinants.

DiscussionA notable prevalence of stress among medical students is a cause of concern, considering its potential impacts on mental health, academic prowess, and, consequently, the delivery of patient care after graduation. The current study seeks to assess potential correlations between perceived stress, anxiety, sleep quality, and academic performance among Moroccan medical students. No gender differences were found in our study population concerning the main sociodemographic characteristics excluding for the students’ economic status, which is similar to the findings of previous researches.20 The uniformity of our study sample and the parity in opportunities for both male and female students could offer potential explanations for these outcomes.

The overall prevalence of stress in our investigation, standing at 62.9% mirrors to the Saudi Arabia study (63.7%),21 but higher than study in Syria (50.6%).22 Potential contributors to these variations include the utilization of different stress assessment tools, the presence of institutional support, levels of mental health awareness, or the influence of sample size.

The current study provided evidence of the significant correlation between perceived stress and sleep quality among Moroccan medical students. It shows that a high level of stress is a major contributor to poor sleep quality. In addition, the average score of sleep quality among non-stressed students was 7.94, whereas this value decrease to 5.38 among stressed students. This is similar to the findings of many investigations conducted in Saudi Arabia and India among medical students.2,11 These results may support the hypothesis that stressed medical students are reducing their sleeping hours to meet various academic and clinical requirements, considering that sleep is not a priority compared to these demands,11 which may heighten their sleep disturbance, especially during exam periods. Physiological investigations have consistently demonstrated a close relationship between sleep, stress, and the hypothalamo–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, providing a possible explanation for the interconnection of these 2 factors.23

Besides, as per our research, students might have a problem falling asleep soon after getting into bed, as measured by sleep latency. This problem could be explained by their high stress’ level since the measure of association between these 2 variables indicated their significant correlation. The other components of sleep quality were also affected by stress including subjective sleep quality, sleep duration, usage of sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction, which may harm students’ learning process.24 In light of these results, the establishment of appropriate interventions targeting university students is required to promote good sleep hygiene to this population and to provide them alternative skills such as time management skills to help them to cope effectively with their stressful environment.

Another significant finding in this study is that there was a significant association between students’ stress scores and anxiety levels. Furthermore, stressed students seem to have anxiety symptoms since 45.8% of them had a high to extremely high-stress level. However, only 8.2% of non-stressed students had this psychosomatic problem. This is in agreement with the findings reported by Saxena et al.25 confirming that stress participates in developing different psychological morbidities among the medical population including anxiety. These results could be explained by the fact that the permanent contact of stressed students with stressors such as exams or contact with patients could lead them to develop more psychological morbidities including anxiety. The decrease in medical students’ well-being could negatively affect patients’ care. This hypothesis is supported by the results of previous studies affirming that increased stress and anxiety levels can affect medical students’ effective functioning and increase the risks for errors.26

Our results revealed also a significant correlation of perceived stress with the decrease in students’ academic performance. This academic accomplishment was assessed by measuring students’ academic, stress management, and studying skills. These confirm some previous findings27 affirming the negative impact of psychological stress on academic performance, but contrasting others.28 The decrease of all these academic skills could negatively affect students’ success by reducing their anticipating, planning, and understanding abilities.27

This study identified that there were no notable variations between genders concerning perceived stress levels, anxiety, sleep quality, and academic performance. This contrasts with earlier research among medical students in Ethiopia, revealing gender differences in self-reported stress and anxiety levels, notably higher among female students.29 The rationale behind our findings may be attributed to the likelihood that both males and females in our study population may employ similar coping mechanisms in response to stressors, contributing to comparable levels of perceived stress and anxiety, which may equally influence their sleep quality and their academic performance.

As this investigation is a cross-sectional study, our research generates only a snapshot of the deep facts. Furthermore, this investigation utilized a survey method; as a result, several types of bias inherent in this type of methodology must be considered, including non-response bias, selection bias, and reporting bias. The study was also conducted in one university and might not be generalized to whole university students. Despite these limitations, the study expanded our knowledge on the association between the main characteristics of psychological morbidity and the decrease of academic performance among medical students. It also provides an insight for the Moroccan university administrators and stakeholder valuable insights for addressing the problem. Additionally, the present results could serve as initial data for subsequent studies with advanced methods and involving multiple centers.

ConclusionsWhile the medical curriculum is a source of stress, if it surmounts an individual psychiatric capacity, it could have detrimental consequences for his mental health. In this study, a good proportion of medical students were stressed. This stress was significantly associated with the decrease in students’ academic performance and sleep quality, in addition to its correlation with anxiety symptoms within our population. These findings highlight the need for adequate interventions targeting medical students to help them develop adaptive strategies for better stress management.

Source of fundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not for- profit sectors.

Ethical approvalFollowing the local legislation, ethical as well as scientific approval for the protocol of the study was obtained from the University Hospital Centre Hassan II of Fez, Morocco (N°17/17; Date: June 2017).

Consent to participateOnly students who fully understood the nature of the survey given in the background and agreed to participate were included.

Consent for publicationNot applicable.

Authors contributionEMH wrote a draft of the manuscript and performed the statistical analyses of the work. AC was involved in the conception and the validation of the questionnaire used in the study. EFS and TN contributed to the conception and design of the study supported the acquisition of data and the statistical analyses. AR contributed to the conception and the design of the study. BM gave final approval of the version to be submitted and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The authors are grateful to the medical students who participated in the study. This study is not funded by any institutions.