The objective is to evaluate the performance of medical and nursing residents on pediatric cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) after training in simulations.

MethodsQuantitative, quasi-experimental study, with an exploratory, descriptive approach that evaluates educational intervention. 16 groups of 5–7 professionals: Moment 0 (M0), simulation at the beginning; Moment 1 (M1), after M0 debriefing; Moment 2 (M2), approximately 3 months after M0. The research instrument was a pediatric cardiorespiratory arrest checklist.

ResultsInvitation to 96 participants, resulting in 85 residents in M0 and M1; 58 residents in M2. In M0, one team got the immediate start of CPR correctly in M1, 50% of the teams got it right, and in M2, 75%. There was a significant difference in M0 and M1. In M0, 68.8% of the classes were icorrect about the compression depth; in M1, 18.8% made mistakes, and in M2, 75%. There was a significant difference in M0 and M1, M1 and M2. In M0, 75% were wrong regarding chest recoil; in M1, 25%, and in M2, still 25%. Statistically, there was a difference. Regarding the 15:2 ratio in compressions and ventilations, 37.5% made mistakes in M0; all scored in M1 (statistically significant difference); and, in M2, 1 group made mistakes. As for compression frequency, in M0 15 did not score, M1 50% errors (significant difference), and 66.7% erros in M2. Alarming data in rhythm check, defibrillation, antiarrhythmic drug, and intravenous access.

ConclusionSimulations at shorter intervals than the average of 129 days seen in the study are recommended.

El objetivo es evaluar el desempeño de médicos y residentes de enfermería en reanimación cardiopulmonar pediátrica tras entrenamiento en simulaciones.

MethodsEstudio cuantitativo, cuasiexperimental, de enfoque exploratorio y descriptivo que evalúa la intervención educativa. 16 grupos de 5 a 7 profesionales: Momento 0 (M0), simulación al inicio; Momento 1 (M1), después del informe M0; Momento 2 (M2), aproximadamente tres meses después de M0. El instrumento de investigación fue una lista de verificación de parada cardiorrespiratoria (PCR) pediátrica.

ResultadosInvitación a 96 participantes resultando 85 residentes en M0 y M1; 58 residentes en M2. En M0, un equipo realizó correctamente el inicio inmediato de la RCP; en M1, el 50% de los equipos acertaron, y en M2, el 75%. Hubo una diferencia significativa en M0 y M1. En M0, el 68,8% de las clases se equivocaron en la profundidad de compresión; en M1, el 18,8% cometió errores, y en M2, el 75%. Hubo una diferencia significativa en M0 y M1, M1 y M2. En M0, el 75% se equivocó en cuanto al retroceso del tórax; en M1, el 25%, y en M2, todavía el 25%. Estadísticamente hubo una diferencia. En cuanto a la relación 15:2 en compresiones y ventilaciones, el 37,5% cometió errores en M0, todos puntuaron en M1 (diferencia estadísticamente significativa) y, en M2, 1 grupo cometió errores. En cuanto a la frecuencia de compresión, en M0 15 no puntuaron, M1 50% de errores (diferencia significativa) y M2 66,7%. Datos alarmantes en cuanto a control del ritmo, desfibrilación, antiarrítmicos y acceso intravenoso.

ConclusiónSe recomiendan simulaciones a intervalos más cortos que el promedio de 129 días observado en el estudio.

The teaching–learning strategy with simulation is expanding in professional training at gaining skills, allowing patient and individual safety within a controlled learning environment.1

Clinical simulation in healthcare is one of the strategies for developing technical and non-technical abilities.2

Simulation provides an ideal environment to promote interprofessional education, allowing professionals from different healthcare areas to interact and collaborate in simulated scenarios, integrating their specific actions and knowledge.3

Specific pediatric emergencies are ideal for teaching with high-precision simulation because they are rare but potentially lethal situations—a concept of high severity and low opportunity.4

There was a growing adoption of the strategy in several pediatric residency programs, mainly focusing on emergencies, skills training, and even teamwork.5

It is suggested that, even when cardiopulmonary resuscitation is performed at low frequency, it is essential that the health professional has ideal skills, although studies indicate that they are lost over time, in approximately 6 months. Training that recycles this knowledge must emphasize the performance of psychomotor skills and improve self-confidence, and must be carried out every 3–6 months.6

We seek to answer: What is the performance evaluation of pediatric cardiopulmonary resuscitation by interprofessional team composed of medical and nursing residents through the teaching–learning strategy with clinical simulation?

Material and methodsThis is a quantitative, quasi-experimental study with an exploratory, descriptive approach that evaluates educational intervention. The project was carried out in an exclusively pediatric hospital in Curitiba-Brazil, with a Simulation Center.

Participants were medical and nursing residents in pediatrics at the institution, with an estimation of 96 participants, who were divided into 16 groups of 5–7 professionals. The signed informed consent form and, each team carried out interprofessional simulation training, being divided into:

- •

Moment 0 (M0): Simulation at the beginning of the meeting to allow assessment of the state of the art.

- •

Moment 1 (M1): Simulation after debriefing from moment 0.

- •

Moment 2 (M2): Simulation after 3 months after moment 0.

All first-, second-, and third-year pediatric medical residents and first- and second-year pediatric nursing residents were included in the study.

Professionals who were not part of the pediatric medical residents and child and adolescent health nursing residency were excluded from the study.

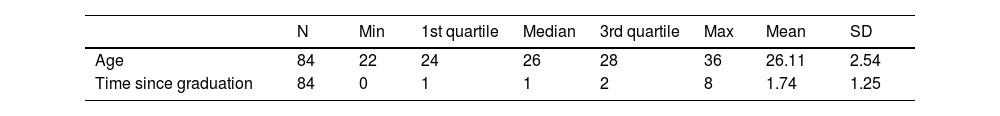

Regarding the participants' epidemiological profile, 84.7% were women, with the following data are available in Table 1:

Regarding the experience with emergency simulation, nursing residents had not previously participated in the PALS – Pediatric Advanced Life Support course. Within medical residents, in turn, 28.23% had taken the PALS, and the average time since then was 12.45 months before participating in the study. It is important to highlight that only resident doctors participated in a theoretical class on CPA 1 month before the study.

Regarding the Briefing, participants were not informed of what would happen in the scenario. Only the objective of providing quality interprofessional care in the face of a pediatric emergency was defined.

The instrument used was a Pediatric Cardiorespiratory Arrest Care Checklist. To validate internal consistency, a Panel of Experts was held for the approval of the instrument. Suggestions for breaking down some questions, mainly related to quality cardiopulmonary resuscitation items in basic life-support, were received. The panel consisted of 5 pediatric intensive care doctors, 1 neonatology pediatrician, and 1 pediatric cardiologist.

The 3 instructors who conducted the simulation and debriefing are qualified in pediatrics and received prior training in simulation.

The scenario was the same, being the case of a 5-year-old male patient who progressed to cardiorespiratory arrest (CRA) in ventricular fibrillation.

Data were analyzed using statistics, with proportions calculated in percentages, and Student's t-tests were applied. Chi-square tests or Fisher's exact tests were applied.

Results96 people were invited, and absences resulted in:

- •

Moment 0 and 1: 85 residents, 16 classes, and 10.89% of absences.

- •

Moment 2: 58 residents, 12 classes, and 42.57% of absences.

In Fig. 1, at moment 0, there was a disparity between questions 1—Identification of CRA and 2—Immediate start of high-quality cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), in which 15 groups got the first one right, and 15 classes did not get the second one right, and the same number got question 6 wrong—performance of high-quality CPR regarding the frequency of 100–120 compressions per minute.

The overall percentage of correct answers in moment 0 was 48.4%, while in moment 1, it was 74.2%, showing a notable acquisition of knowledge immediately after the intervention. The percentages according to the items evaluated can be seen in Table 2.

Percentages of correct answers.

| Moment 0 (%) | Moment 1 (%) | Moment 2 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | 94 | 100 | 100 |

| Q2 | 6 | 50 | 75 |

| Q3 | 31 | 81 | 25 |

| Q4 | 25 | 75 | 75 |

| Q5 | 62 | 100 | 92 |

| Q6 | 6 | 50 | 33 |

| Q7 | 44 | 81 | 100 |

| Q8 | 94 | 100 | 100 |

| Q9 | 81 | 75 | 67 |

| Q10 | 69 | 94 | 58 |

| Q11 | 81 | 94 | 83 |

| Q12 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| Q13 | 56 | 81 | 92 |

| Q14 | 31 | 44 | 33 |

| Q15 | 50 | 81 | 83 |

| Q16 | 44 | 81 | 83 |

Q1 - PCR identification.

Q2 - Immediate start of high-quality CPR.

Q3 - High-quality CPR performance in terms of compression depth.

Q4 - Performance of high-quality CPR regarding chest recoil.

Q5 - High-quality CPR performance in relation to 15 compressions/2 ventilations.

Q6 - High-quality CPR performance at a frequency of 100 to 120 compressions per minute.

Q7 - High-quality CPR performance with rhythm checks every 2 min.

Q8 - Installation of pads/electrodes and activation of the monitor/defibrillator.

Q9 - PCR identification: VF or pulseless VT.

Q10 - Safely perform a defibrillation attempt at 2 J/kg.

Q11 - After each shock, immediately restart CPR, starting with chest compressions.

Q12 - Establishing IO or IV access.

Q13 - Preparation and administration of the epinephrine dose at appropriate intervals.

Q14 - Safe delivery of the 2nd shock at 4 J/kg (subsequent doses of 4–10 J/kg, should not exceed 10 J/kg or standard adult dose for that defibrillator).

Q15 - Preparation and administration of the appropriate dose of antiarrhythmic drug (amiodarone or lidocaine) at the appropriate time.

Q16 - Verbalization of the possible need for additional doses of epinephrine and antiarrhythmic medication (amiodarone or lidocaine), and consideration of reversible causes of arrest (Hs and Ts).

When comparing the general percentage of correct answers, from moment 1 (74.2%) to moment 2 (69.3%), there was a decrease in the gain of technical knowledge. However, when comparing the moment 0 with the moment 1—48.4%, an evolution in learning can still be observed.

At moment 0, questions 1—Identification of the CRA—and 8—Installation of pads/electrodes and activation of the monitor/defibrillator presented the highest percentages of correct answers (94%).

Regarding the worst performances at moment 0, Question 12—Verbalization of second intravenous access obtained 100% of errors. Questions 2—Immediate start of high-quality CPR and 6—Performance of high-quality CPR regarding frequency of 100–120 compressions per minute had 94% of errors.

In Fig. 2, at moment 1, questions 1 and 8 remained 100% compliant, and addition of question 5—Performance of high-quality CPR regarding the 15 compressions/2 ventilations ratio. Questions 11—After each shock, immediate restart of CPR, starting with chest compressions and 10—Safe performance of a defibrillation attempt at 2 J/kg had 94% correct answers.

As for the lower performances in moment 1, Question 12—Verbalization of second intravenous access remained with 100% errors. On the other hand, a reduction in errors was observed as the next worst performance: in Question 14—Safe delivery of the 2nd shock at 4 J/kg, there was 56% non-compliance.

In Fig. 3, at moment 2, we observed the maintenance of 100% of correct answers in questions 1 and 8 of moment 1 and also an increase from 81% to 100% of correct answers in question 7—Performance of high-quality CPR regarding rhythm checking at every 2 min. Question 12, which remained at moments 0 and 1 with 100% of errors, only improved to 8% of correct answers.

When comparing means by variables, we ask whether there was a difference within the number of correct answers. When comparing means variables, we asked whether there was a difference within the number of correct answers. Using the variable moment (Moment 0×Moment 1), there was a significant difference (p value <.05) in questions 2—Immediate start of high-quality CPR, 3—Performance of high-quality CPR regarding compression depth, 4—Performance of high-quality CPR regarding chest recoil, 5—Performance of high-quality CPR regarding the ratio of 15 compressions/2 ventilations, and 6—Performance of high-quality CPR regarding the frequency of 100–120 compressions per minute.

Still using the variable moment (Moment 1×Moment 2), there was a significant difference (p value <.05) only in question 3—High-quality CPR performance regarding compression depth.

Finally, in the comparison of the variable moment (Moment 0×Moment 2), there was a significant difference (p value <.05) in questions 4—Performance of high-quality CPR regarding chest recoil and 7—Performance of high-quality CPR regarding rhythm checking every 2 min.

DiscussionCRA identificationIn the study, at moment 0, only one team did not score the CRA identification item. At moments 1 and 2, everyone scored.

In a 2020 study, professionals reported relevant points in identifying CRA, but none addressed the 3 signs required for this identification.7

In a study with intensive care nurses, 40% were unable to identify the signs of CRA, but 93% reported being able to provide care.8

Finally, in the comparison of the variable moment (Moment 0×Moment 2), there was a significant difference (p value <.05) in questions 4—Performance of high-quality CPR regarding chest recoil and 7—Performance of high-quality CPR regarding rhythm checking every 2 min.9

In a 2021 study, 71% of nurses correctly chose the assessment sequence that should be followed when identifying CRA with the recommendation that it be agile.10

In Santos et al., after a simulation intervention on CRA in adults, the average number of correct answers related to recognition went from 53.8% in the pre-test to 60.4% in the post-test.11

Immediate start of high-quality CPRIn this study, at moment 0, only one team reached the item immediate start of CPR. 50% of the teams managed to get this factor correctly in moment 1, while 75% did in moment 2. It is known that the time to start CPR maneuvers is one of the main components for success, as professionals have 10 s to identify CRA.12

According to statistical tests, there was a significant difference between the values of this item when comparing moments 0 and 1, reinforcing that there is a real impact of the methodology on immediate learning.

In a study by Bertolo et al., 29 (64.4%) medical and nursing professionals responded that CPR in pediatrics should begin with compressions. Moreover, in this study, when asked about the first attitude to be taken in the face of CRA in pediatrics, 42% were unable to answer.13

In a study by Kuzma et al., among professionals who provided CPR in the context of an in situ mock code, 46.7% of cases started the maneuvers promptly.14

High-quality CPR performance in terms of compression depthIn this research, at moment 0, 68.8% of the classes got the item about compression depth wrong. At moment 1, only 18.8% of the classes failed, whih represents an improvement in performance. At moment 2, there was an increase in errors, with 75% of the classes not scoring.

Still according to the statistical tests, there was a significant difference between the numbers when comparing moment 0 and 1, and moment 1 and 2.

In the study by Bertolo et al., the multidisciplinary research subjects responded in 35.55% that it should be compressed about 1½ inches (4 cm) in babies and 2 inches (5 cm) in children.13 When based on evidence, it is suggested that it may not be possible to compress up to half the anteroposterior diameter, with a recommended depth of 1½ inches (4 cm) in babies and 2 inches (5 cm) in children.15

In the research by Fernandes et al., 2 groups of nursing students were formed, out of which the first responded to a post-test with only theoretical classes, and the second responded after a simulated scenario. As for the minimum depth, 78.3% of the first group answered that it would be 3 cm, and only 21.7% adequately answered 5 cm, while in the second group, 58.3% had the correct answer.16

High-quality CPR performance regarding chest recoilThe research showed that 75% of the groups did not perform well in terms of chest recoil during compressions performed in moment 0. Then, at moment 1, there was an improvement for 25% of the wrong groups and, at moment 2, 25%.

When comparing the results from moment 0 to 1 statistically, there is a significant difference that demonstrates that the simulations provided a gain in practical knowledge immediately after the intervention. There is also statistical significance between moment 0 and moment 2, thus being indicative of learning retention.

In the research by Fernandes et al., in the group of nursing students who responded to the assessment without simulation, 87% of responses stated that there was no need for full recoil of the chest wall between compressions. In the group that received the simulation intervention, 79.2% had the same response.16

High-quality CPR performance in relation to 15 compressions/2 ventilationsRegarding CPR quality given the compressions and ventilations ratio of 15:2, 37.5% of the groups did not get it right at moment 0, all the groups managed to score at moment 1, and only 1 group (8.3%) made mistakes again in moment 2. The statistical comparison between moments 0 and 1 brings a significant difference which, again, shows the positive impact of the simulation.

In the study by Bertolo et al., 51.11% of healthcare professionals responded that the ratio of compression and ventilation in pediatrics is 15:2, while 48.89% said 30:2.13

The American Heart Association emphasizes that the effectiveness of CPR focuses on compressions and ventilations as essential parts, being applied according to a logical association.17

In a 2020 study, among professionals who started CPR when faced with an in situ mock code, 50% performed the correct compressions when the compressions/ventilations ratio 15:2.14

High-quality CPR performance at a frequency of 100–120 compressions per minuteIn this item, at moment 0, 15 groups did not score assertively, while at moment 1, there was a reduction in the number of classes that made mistakes to 50%, and again an increase to 66.7% at moment 2. Through statistical tests, a significant difference was proven between the numbers at moment 0 and 1, highlighting the immediate impact of the simulation.

In a 2017 study, 80.6% of professionals highlighted the need for chest compressions during CPR, which should be rhythmic, strong, and with a minimum of 100 and a maximum of 120 compressions per minute.18

In a 2020 study, among professionals who started CPR when faced with an in situ mock code, 1 case (8.3%) performed the correct compressions when frequency and depth were evaluated.14

In Semark et al., chest compressions in CRA regarding frequency and depth in the hospital were evaluated, resulting in low quality in 96% of the cases.19

High-quality CPR performance with rhythm checks every 2 minA total of 56.2% of teams got this item wrong at moment 0, which was reduced to 18.8% mistake at moment 1, and none at moment 2. This difference between moments 0 and 2 was significantly proven by statistical testing, suggesting retention of learning.

In a study by Oliveira, using an evaluative checklist, out of the 20 items listed, 5 were not applied by the participants in the simulated activity, one of which was checking the heart rate every 2 min.20

In a study by Silva et al., only 12.5% of participants answered the question regarding the use of the defibrillator correctly.10

In a 2020 study, through the in situ mock code, it was observed that only 33.3% of professionals checked heart rhythm at the appropriate time.14

Installation of pads/electrodes and activation of the monitor/defibrillatorA total of 6.2% of the teams did not get this stage right at moment 0, bringing the number of errors to zero in the next 2 moments.

CRA identification: ventricular fibrillation (VF) or pulseless ventricular tachycardia (VT)At moment 0, 18.8% of the teams did not identify CRA rhythm, 25% at moment 1, and 33.3% at moment 2.

In Santos et al., after a simulation intervention on CRA in adults, the average percentage of correct answers in the identification of shock based on the identification of rhythms was of 32.6% in the pre-test, and 67.4% in the post-test.11

In a study by Silva et al., 12.5% of nursing professionals who responded to the survey were unable to identify existing CRA rhythms.10 In Prestes and Menetrier (2017), 44.4% of professionals responded that asystole would be the only rhythm of CRA.21

Safe performance of an attempt of defibrillation at 2 J/kgAt moment 0, 31.2% of groups missed safe defibrillation, 6.2% at moment 1, and 41.7% at moment 2.

In the study by Silva et al., 58.1% of professionals reported knowledge of the use of a defibrillator.18 In the research by Alves et al. (2013), 50% of professionals answered the question about the voltage to be administered correctly.22

In Moura et al., regarding the professionals consulted about the initial defibrillation load, 13% of nurses and 50% of technicians were unable to answer, and 30.43% of nurses and 17.95% of technicians had an incorrect answer.23

After each shock, immediately restart CPR, starting with chest compressionsThis item was not effective in 18.8% of the groups at moment 0, 6.2% still made mistakes immediately after, and 16.7% made mistakes after the stipulated period.

In a 2017 study, when comparing a group of nursing students who responded to the assessment without simulation and another with simulation, 87% of the first team and 70.8% of the second considered that the rescuer should minimize interruptions in chest compressions before and after the shock.16

Verbalization of second IV accessBoth at moments 0 and 1, 100% of the classes did not verbalize the second intravenous access. At moment 2, 91.7% stopped verbalizing.

To allow medication administration, a venous access is required, which is complicated in cases of pediatric CRA. The best access is that when the puncture does not hinder CPR maneuvers and allows an adequate caliber.24

Preparation and administration of the epinephrine dose at appropriate intervalsThere was no adequate administration in 43.8% of the classes at moment 0, 18.8% at moment 1, and 8.3% at moment 2.

The use of adrenaline in the first minutes of actions is associated with a significant number of cases that had spontaneous circulation return more quickly.17

In a 2017 study, 80.6% of nurses chose epinephrine as their first choice drug.18

In Bertolo et al., 88.88% of health professionals cited adrenaline as their first drug of use, and 11.11% did not respond.13

In a study by Silva et al., 84.4% of participants responded that epinephrine should only be used in CRA without shockable heart rhythm, contradicting the recommendation that it always be administered regardless of the rhythm.10

In research by Kuzma et al., among professionals faced with an in situ mock code, 100% of the leaders used epinephrine, and in 75% of cases, the frequency of its administration was correct.14

Safe delivery of the 2nd shock at 4 J/kg (subsequent doses of 4–10 J/kg, not to exceed 10 J/kg or standard adult dose for that defibrillator)This item was unsuccessful in 68.8% of the teams at moment 0, 56.2% at moment 1, and 66.7% at moment 2.

In Santos et al., after a simulation intervention on CRA in adults, the average number of correct answers related to handling of defibrillator went from 44.4% in the pre-test to 51.6% in the post-test.11

In Fernandes et al., when comparing a group of nursing students who responded to the assessment without simulation and another with simulation, 82.6% of the first team and half of the second one indicated the consideration of an initial load of 2 J/kg and the subsequent shocks of at least 4 K/kg as incorrect.16

Preparation and administration of the appropriate dose of antiarrhythmic drug (amiodarone or lidocaine) at the appropriate momentHalf of the groups did not get this question correct at moment 0, 18.8% at moment 1, and 16.7% at moment 2.

Amiodarone can be used for the treatment of refractory or recurrent VF/pulseless VT shock in pediatrics. If not available, lidocaine can be considered.15

Verbalization of the possible need for additional doses of epinephrine and antiarrhythmic medication (amiodarone or lidocaine), and consideration of reversible causes of arrest (Hs and Ts)More than half of the classes (56.2%) did not perform this step properly in moment 0. There was a significant improvement in moment 1, with 18.8% of errors, and 16.7% in moment 2.

In 2015, guidelines suggest that in both ventricular fibrillation and pulseless ventricular tachycardia refractory to shocks, lidocaine or amiodarone can be administered.17

In a 2020 study, they emphasize that the cause of such a CRA must be actively sought to be treated as soon as possible.25

Thus, simulations are recommended to gain skills and clinical practice at shorter intervals than the average of 129 days seen in the study. Therefore, a continuing education program with clinical simulations that frequently brings professionals together is suggested.

It is also noted that there are few studies using the simulation methodology to train professionals in their work environment, with most studies involving training or questionnaire research.

Such data legitimize the need for qualification of health professionals providing direct patient care, in addition to highlighting the importance of ongoing in-service education with the aim of increasing success rates in the face of CRAs.

Ethical statementThe work was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Faculdades Pequeno Principe under Consubstantiated Opinion no. 5.131.695. The participants were informed and signed the Free and Informed Consent Form (FICF).

All authors read and approved the content of the manuscript. All authors contributed fundamentally to the completion of this study.

FundingThere was no funding.