Medical schools are responsible for breaking bad news training, which should be focused on the students; therefore, the purpose of this study is to identify undergraduate medical students’ perceptions regarding the best way to train them.

MethodsCross-sectional anonymous survey applied between 438 >18-years-old Colombian medicine students.

ResultsThe students feel unprepared to breaking bad news; even without formal training, they believe they are better at breaking bad news as they advance in their training due to their observation of other clinicians and their personal experiences. A higher proportion of male students consider themselves empathetic than female students, but advanced male students report more frequently that their empathic capacity has decreased throughout their career more frequently than female students of the same academic level.

DiscussionThis information will allow the medical school to modify the curriculum to offer proper training to its students.

ConclusionVery few students have received formal training regarding this topic, and most of them are interested in training.

Las escuelas de Medicina son las responsables del entrenamiento en dar malas noticias, el cual ha de estar enfocado en los estudiantes, por lo que el propósito de este estudio es identificar sus percepciones acerca de la mejor forma para entrenarles.

MétodosEstudio trasversal anónimo entre 438 estudiantes >18 años de un programa colombiano de Medicina.

ResultadosLos estudiantes no se sienten preparados para dar malas noticias. Aun sin entrenamiento formal, ellos creen que su capacidad para dar malas noticias mejora a medida que avanza su entrenamiento médico. Hay una mayor proporción de estudiantes varones que mujeres que se consideran empáticos, pero también ellos reconocen con más frecuencia que ellas que su capacidad empática disminuye con el avance de sus estudios.

DiscusiónLa información recolectada puede permitir a las escuelas de Medicina modificar su currículo para ofrecer entrenamiento más adecuado a sus estudiantes en dar malas noticias.

ConclusiónMuy pocos estudiantes han recibido capacitación formal sobre este tema y la mayoría de ellos están interesados ??en capacitarse.

Communication is one of the key skills of physicians.1 These capabilities are specific, integrative, enduring, and performance-focused: they can be learned, correlate with other abilities, and be measured.2 A critical aspect of communication is to give appropriate, clear, and pertinent information to the patient and their family members about their condition.3 Medical students frequently have difficulty communicating bad news and require special training to do it properly. This difficult experience burdens them with insecurities and fears and makes them feel dissatisfied.4 The quality of the experience will also shape how they will deliver bad news as future physicians: most doctors who have trouble communicating bad news and have not gotten formal training become elusive and uninterested in learning how to do it right.5 Many doctors do not even question whether they are doing it right or wrong.6 Patients become distrustful and unsatisfied with the quality of the information and how it was delivered.7,8 This contrasts with the responsibility that medical schools have regarding training in breaking bad news (BBN), which has to be an explicit and qualifiable element of the curriculum that allows the student to pass from the periphery to the center of the interactions between patients, relatives, and doctors.9

Various protocols for delivering bad news had been designed, and several proposals about teaching this skill in different clinical contexts had been proposed.10 Additionally, teaching theories propose that no matter the didactic strategies available, the process is focused on the student, and the main element is the empathy that the student feels and expresses according to the situation.11 The main objective of this study is to identify the perception of undergraduate students regarding their ability for BBN and their perceptions about the ways to train them. It is the first step in a process that seeks to guarantee the training on this subject for medical students in a formal curriculum way.12

MethodsA cross-sectional study was done via an anonymous survey among all medical students over 18 years old registered in the Medicine program in a public university in Colombia. The Review Board of the university approved this project. The survey included three demographical items and 32 questions about future moments in which bad news has to be delivered, what strategies they would use to do so, and how they can improve this skill. A Likert-type survey was created for these 32 items13; all but one item were tools used in similar research projects made in other environments with related objectives.14–18 Items 1–3 were demographical; items 4–28 explore three topics (the perceived capacity for BBN, the most challenging parts of the process, and strategies used during the process) with five answers from “Agree” to “Disagree”; and, items 29–35 explored the student's opinion about the importance of seven pedagogical strategies for training them to BBN, with five answers ranged from “Essential” to “Unimportant”. The surveys were transcribed with a double entry in RedCap® to control possible transcription errors.

Socio-demographic data was analyzed in proportions or central tendency measures (mean and standard deviation); the not-normal data were reported with median and interquartile range (IQR). According to the situation, differences were evaluated via the χ2, χ2 of lineal tendency (χ2LT), or Wilcoxon tests. Answers were described through proportions for each one of the items presented. Answers from items 4 to 35 were grouped into two categories: “Agree” and “Somewhat agree” as a new category called “Expected answers”, and the other answers were considered “Non-expected answers”. According to the situation, differences between these dichotomic categories were evaluated with χ2 or Fisher's exact tests, considered statistically significant when α<0.05. Finally, the best possible logistics model was to estimate the associative strength between each item's Expected answers categories with the demographic and academic level variables. The data from the first-year students is the referent category, with which the data of the other academic levels are compared. Data analysis was made with Stata/SE® 16.1 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA, 2020).

ResultsOf 645 students registered in the medicine program during the second semester of 2019, from June to November 2019, 438 (67.9%) students completed the questionnaire. Of these, 108 were first-year students out of 123 enrolled (response rate: 87.8%), 101 out of 125 enrolled of the second-year (80.6%), 71 out of 100 enrolled of third-year (71.0%), 87 out of 95 enrolled of fourth-year (91.6%), 43 out of 96 enrolled of fifth-year (44.8%), and 28 out of 106 enrolled of sixth-year (26.4%). Half of all the fifth- and sixth-year students were out from the medical school's campus, and they were not available at the time of the survey.

Two hundred and thirty (52.5%) of the participants were females, 207 (47.3%) were males, and one (0.2%) do not answer about gender. The age range of participants was between 18 and 34 years old. The median age of participants was 21 years old (IQR 19–22 years). The woman's median age was lower than the men's median age; there was no difference in the proportion of sex per academic level, though there was a difference regarding age (data not shown), which was expected.

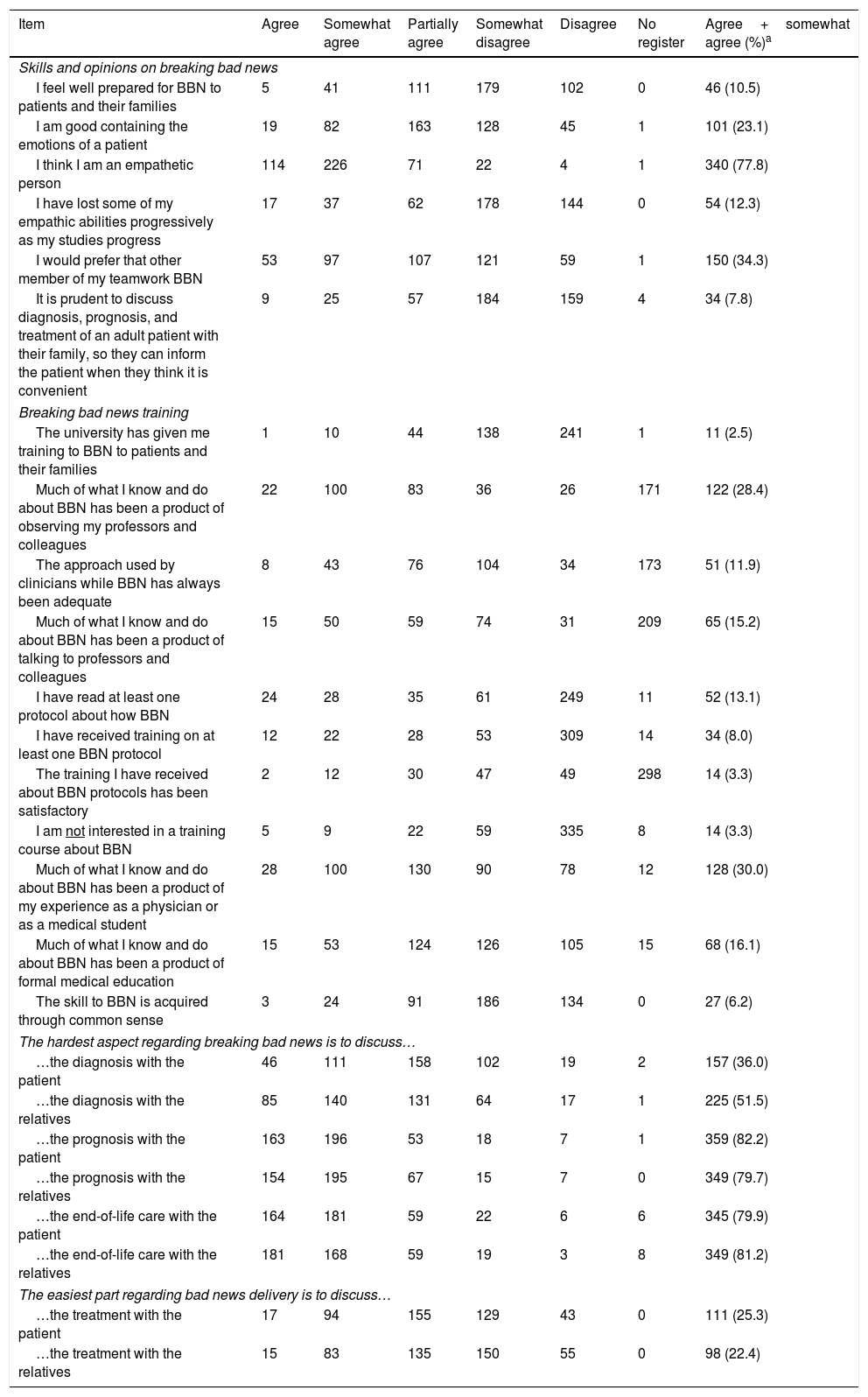

Table 1 shows the students’ answers to all questions in the first three survey domains related to BBN. As findings highlight, more than three-quarters of the student group claim to be empathetic (340/437, 77.8%), but a third of the group would prefer other health practitioners to communicate bad news (150/437, 34.3%). Simultaneously, less than a quarter of the students consider themselves capable of supporting the patient's emotions (101/437, 23.1%), and only one in ten considers being ready to deliver bad news (46/438, 10.5%). Very few students have received formal training regarding this topic (46/438, 10.5%), which is related to the number of younger students who have not yet experienced clinical practice. Only one in 30 students were not interested in any training regarding the topic (14/424, 3.3%). More than half of the students manifest difficulties in talking with patients and their relatives about the prognosis or passing away, but it is not as hard as talking about the diagnosis. Additionally, it seems as if it is easier to talk about those issues with the family than with the patient.

Answers on breaking bad news reported by 438 surveyed students.

| Item | Agree | Somewhat agree | Partially agree | Somewhat disagree | Disagree | No register | Agree+somewhat agree (%)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skills and opinions on breaking bad news | |||||||

| I feel well prepared for BBN to patients and their families | 5 | 41 | 111 | 179 | 102 | 0 | 46 (10.5) |

| I am good containing the emotions of a patient | 19 | 82 | 163 | 128 | 45 | 1 | 101 (23.1) |

| I think I am an empathetic person | 114 | 226 | 71 | 22 | 4 | 1 | 340 (77.8) |

| I have lost some of my empathic abilities progressively as my studies progress | 17 | 37 | 62 | 178 | 144 | 0 | 54 (12.3) |

| I would prefer that other member of my teamwork BBN | 53 | 97 | 107 | 121 | 59 | 1 | 150 (34.3) |

| It is prudent to discuss diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of an adult patient with their family, so they can inform the patient when they think it is convenient | 9 | 25 | 57 | 184 | 159 | 4 | 34 (7.8) |

| Breaking bad news training | |||||||

| The university has given me training to BBN to patients and their families | 1 | 10 | 44 | 138 | 241 | 1 | 11 (2.5) |

| Much of what I know and do about BBN has been a product of observing my professors and colleagues | 22 | 100 | 83 | 36 | 26 | 171 | 122 (28.4) |

| The approach used by clinicians while BBN has always been adequate | 8 | 43 | 76 | 104 | 34 | 173 | 51 (11.9) |

| Much of what I know and do about BBN has been a product of talking to professors and colleagues | 15 | 50 | 59 | 74 | 31 | 209 | 65 (15.2) |

| I have read at least one protocol about how BBN | 24 | 28 | 35 | 61 | 249 | 11 | 52 (13.1) |

| I have received training on at least one BBN protocol | 12 | 22 | 28 | 53 | 309 | 14 | 34 (8.0) |

| The training I have received about BBN protocols has been satisfactory | 2 | 12 | 30 | 47 | 49 | 298 | 14 (3.3) |

| I am not interested in a training course about BBN | 5 | 9 | 22 | 59 | 335 | 8 | 14 (3.3) |

| Much of what I know and do about BBN has been a product of my experience as a physician or as a medical student | 28 | 100 | 130 | 90 | 78 | 12 | 128 (30.0) |

| Much of what I know and do about BBN has been a product of formal medical education | 15 | 53 | 124 | 126 | 105 | 15 | 68 (16.1) |

| The skill to BBN is acquired through common sense | 3 | 24 | 91 | 186 | 134 | 0 | 27 (6.2) |

| The hardest aspect regarding breaking bad news is to discuss… | |||||||

| …the diagnosis with the patient | 46 | 111 | 158 | 102 | 19 | 2 | 157 (36.0) |

| …the diagnosis with the relatives | 85 | 140 | 131 | 64 | 17 | 1 | 225 (51.5) |

| …the prognosis with the patient | 163 | 196 | 53 | 18 | 7 | 1 | 359 (82.2) |

| …the prognosis with the relatives | 154 | 195 | 67 | 15 | 7 | 0 | 349 (79.7) |

| …the end-of-life care with the patient | 164 | 181 | 59 | 22 | 6 | 6 | 345 (79.9) |

| …the end-of-life care with the relatives | 181 | 168 | 59 | 19 | 3 | 8 | 349 (81.2) |

| The easiest part regarding bad news delivery is to discuss… | |||||||

| …the treatment with the patient | 17 | 94 | 155 | 129 | 43 | 0 | 111 (25.3) |

| …the treatment with the relatives | 15 | 83 | 135 | 150 | 55 | 0 | 98 (22.4) |

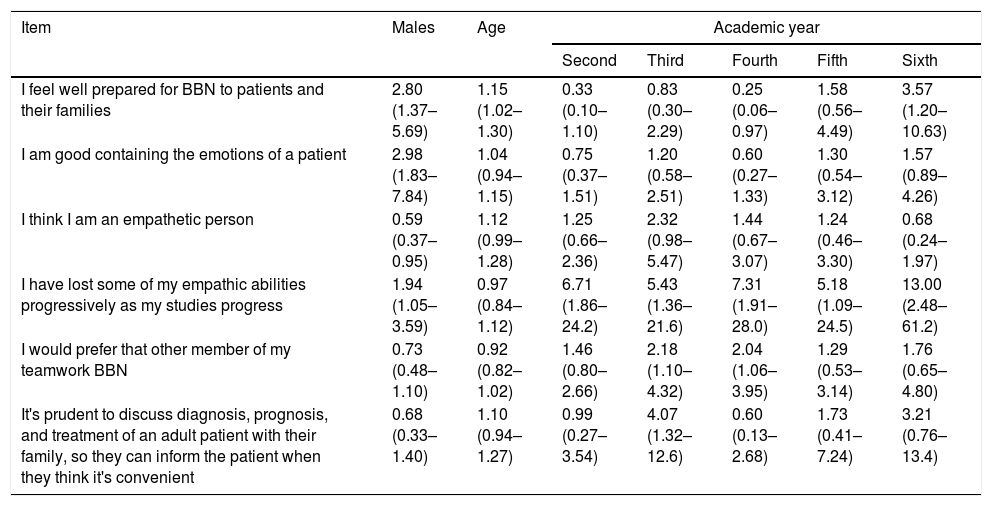

Table 2 presents the best logistical model related to each item's Expected answers and the independent variables (age, sex, and academic level): Men refer to less empathy than women, and their capacity for empathy decreases as training advances; however, they consider themselves better at BBN, just as older students. The third- and fourth-level students also consider themselves as such, though they prefer that others deliver the bad news because they see themselves as unprepared. Third-year students, who have just finished their first clinical practice with adult patients, prefer relatives delivering the bad news to the patient.

Logistic regression models (OR and 95% CI) for the ‘agree’ and ‘somewhat agree’ answers regarding the affirmations about skills and opinions on breaking bad news.

| Item | Males | Age | Academic year | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second | Third | Fourth | Fifth | Sixth | |||

| I feel well prepared for BBN to patients and their families | 2.80 (1.37–5.69) | 1.15 (1.02–1.30) | 0.33 (0.10–1.10) | 0.83 (0.30–2.29) | 0.25 (0.06–0.97) | 1.58 (0.56–4.49) | 3.57 (1.20–10.63) |

| I am good containing the emotions of a patient | 2.98 (1.83–7.84) | 1.04 (0.94–1.15) | 0.75 (0.37–1.51) | 1.20 (0.58–2.51) | 0.60 (0.27–1.33) | 1.30 (0.54–3.12) | 1.57 (0.89–4.26) |

| I think I am an empathetic person | 0.59 (0.37–0.95) | 1.12 (0.99–1.28) | 1.25 (0.66–2.36) | 2.32 (0.98–5.47) | 1.44 (0.67–3.07) | 1.24 (0.46–3.30) | 0.68 (0.24–1.97) |

| I have lost some of my empathic abilities progressively as my studies progress | 1.94 (1.05–3.59) | 0.97 (0.84–1.12) | 6.71 (1.86–24.2) | 5.43 (1.36–21.6) | 7.31 (1.91–28.0) | 5.18 (1.09–24.5) | 13.00 (2.48–61.2) |

| I would prefer that other member of my teamwork BBN | 0.73 (0.48–1.10) | 0.92 (0.82–1.02) | 1.46 (0.80–2.66) | 2.18 (1.10–4.32) | 2.04 (1.06–3.95) | 1.29 (0.53–3.14) | 1.76 (0.65–4.80) |

| It's prudent to discuss diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of an adult patient with their family, so they can inform the patient when they think it's convenient | 0.68 (0.33–1.40) | 1.10 (0.94–1.27) | 0.99 (0.27–3.54) | 4.07 (1.32–12.6) | 0.60 (0.13–2.68) | 1.73 (0.41–7.24) | 3.21 (0.76–13.4) |

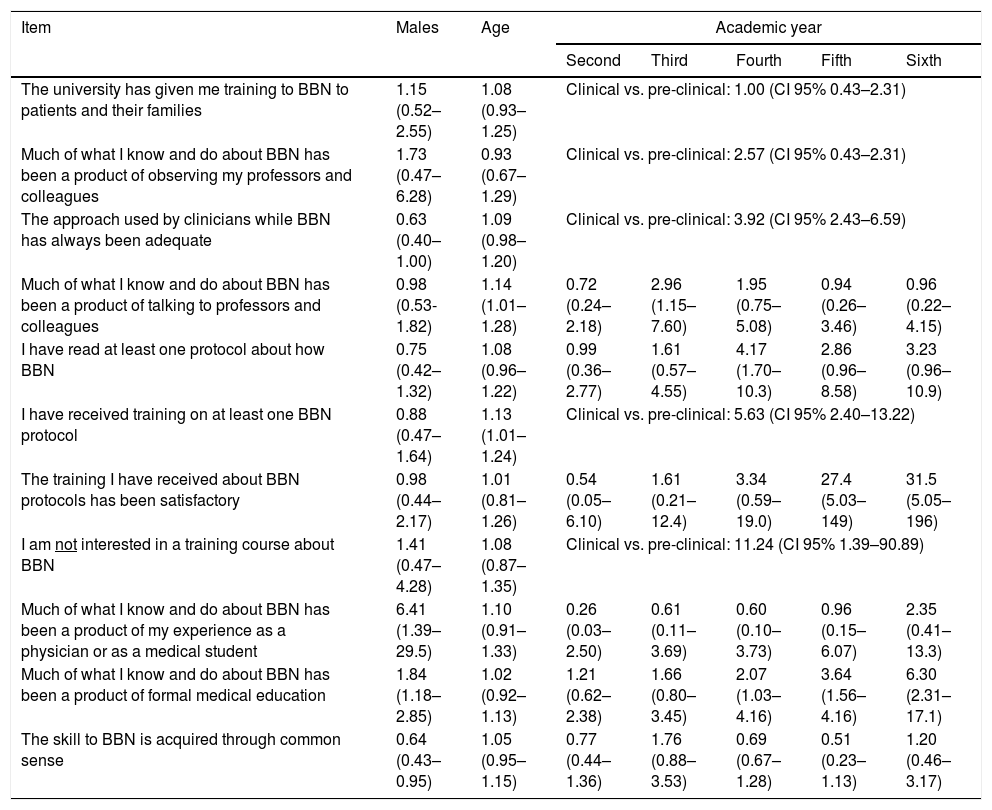

Table 3 presents the logistic model about the students’ BBN training; shows that men highlight experience as the origin of their methods and expertise in the topic, instead of common sense. Students in clinical practice and older students say they have received training in some protocol regarding bad news communication; the students who do not wish to know about any training are in this group. The last observation in this part of the study shows that students frequently recognize that what they have seen regarding bad news is adequate at higher academic levels.

Logistic regression models (OR and 95% CI) for the ‘agree’ and ‘somewhat agree’ answers regarding breaking bad news training.

| Item | Males | Age | Academic year | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second | Third | Fourth | Fifth | Sixth | |||

| The university has given me training to BBN to patients and their families | 1.15 (0.52–2.55) | 1.08 (0.93–1.25) | Clinical vs. pre-clinical: 1.00 (CI 95% 0.43–2.31) | ||||

| Much of what I know and do about BBN has been a product of observing my professors and colleagues | 1.73 (0.47–6.28) | 0.93 (0.67–1.29) | Clinical vs. pre-clinical: 2.57 (CI 95% 0.43–2.31) | ||||

| The approach used by clinicians while BBN has always been adequate | 0.63 (0.40–1.00) | 1.09 (0.98–1.20) | Clinical vs. pre-clinical: 3.92 (CI 95% 2.43–6.59) | ||||

| Much of what I know and do about BBN has been a product of talking to professors and colleagues | 0.98 (0.53-1.82) | 1.14 (1.01–1.28) | 0.72 (0.24–2.18) | 2.96 (1.15–7.60) | 1.95 (0.75–5.08) | 0.94 (0.26–3.46) | 0.96 (0.22–4.15) |

| I have read at least one protocol about how BBN | 0.75 (0.42–1.32) | 1.08 (0.96–1.22) | 0.99 (0.36–2.77) | 1.61 (0.57–4.55) | 4.17 (1.70–10.3) | 2.86 (0.96–8.58) | 3.23 (0.96–10.9) |

| I have received training on at least one BBN protocol | 0.88 (0.47–1.64) | 1.13 (1.01–1.24) | Clinical vs. pre-clinical: 5.63 (CI 95% 2.40–13.22) | ||||

| The training I have received about BBN protocols has been satisfactory | 0.98 (0.44–2.17) | 1.01 (0.81–1.26) | 0.54 (0.05–6.10) | 1.61 (0.21–12.4) | 3.34 (0.59–19.0) | 27.4 (5.03–149) | 31.5 (5.05–196) |

| I am not interested in a training course about BBN | 1.41 (0.47–4.28) | 1.08 (0.87–1.35) | Clinical vs. pre-clinical: 11.24 (CI 95% 1.39–90.89) | ||||

| Much of what I know and do about BBN has been a product of my experience as a physician or as a medical student | 6.41 (1.39–29.5) | 1.10 (0.91–1.33) | 0.26 (0.03–2.50) | 0.61 (0.11–3.69) | 0.60 (0.10–3.73) | 0.96 (0.15–6.07) | 2.35 (0.41–13.3) |

| Much of what I know and do about BBN has been a product of formal medical education | 1.84 (1.18–2.85) | 1.02 (0.92–1.13) | 1.21 (0.62–2.38) | 1.66 (0.80–3.45) | 2.07 (1.03–4.16) | 3.64 (1.56–4.16) | 6.30 (2.31–17.1) |

| The skill to BBN is acquired through common sense | 0.64 (0.43–0.95) | 1.05 (0.95–1.15) | 0.77 (0.44–1.36) | 1.76 (0.88–3.53) | 0.69 (0.67–1.28) | 0.51 (0.23–1.13) | 1.20 (0.46–3.17) |

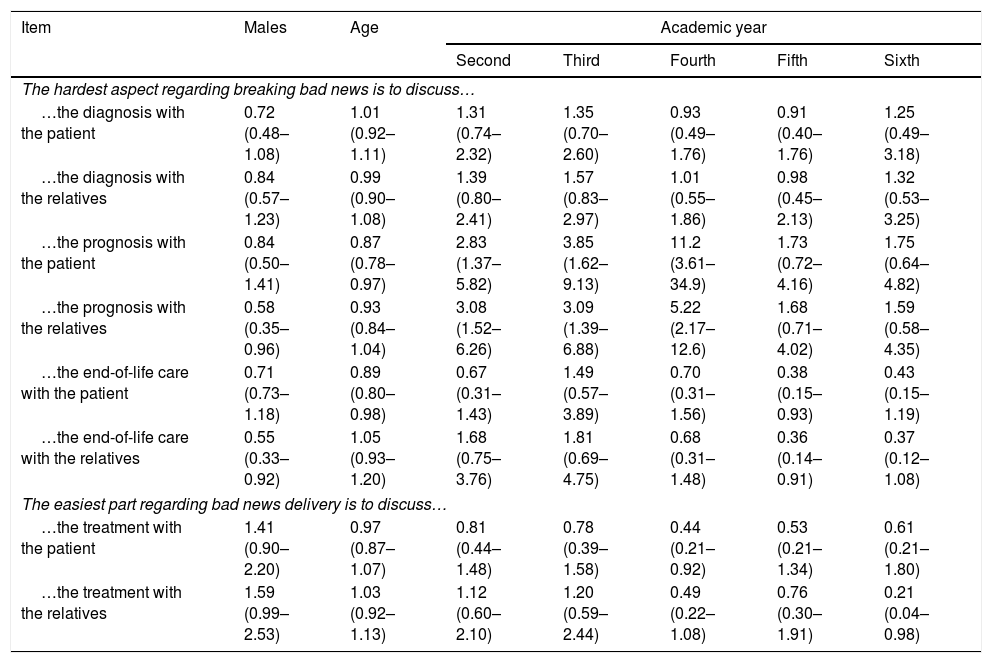

As seen in the logistical model of Table 4, men consider it harder to talk with the family about the patient's diagnosis and prognosis; however, it is even harder for them to talk about passing away with the patients than female students. Older male students affirm that talking with patients about prognosis or passing away is an easy task with less frequency than female students. On the other hand, students from the first to fourth years find it harder to talk about prognosis with the family as much as with the patient. All models have adequate goodness-of-fit.

Logistic regression models (OR and 95% CI) for the ‘agree’ and ‘somewhat agree’ answers regarding the hardest and easiest aspects of breaking bad news.

| Item | Males | Age | Academic year | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second | Third | Fourth | Fifth | Sixth | |||

| The hardest aspect regarding breaking bad news is to discuss… | |||||||

| …the diagnosis with the patient | 0.72 (0.48–1.08) | 1.01 (0.92–1.11) | 1.31 (0.74–2.32) | 1.35 (0.70–2.60) | 0.93 (0.49–1.76) | 0.91 (0.40–1.76) | 1.25 (0.49–3.18) |

| …the diagnosis with the relatives | 0.84 (0.57–1.23) | 0.99 (0.90–1.08) | 1.39 (0.80–2.41) | 1.57 (0.83–2.97) | 1.01 (0.55–1.86) | 0.98 (0.45–2.13) | 1.32 (0.53–3.25) |

| …the prognosis with the patient | 0.84 (0.50–1.41) | 0.87 (0.78–0.97) | 2.83 (1.37–5.82) | 3.85 (1.62–9.13) | 11.2 (3.61–34.9) | 1.73 (0.72–4.16) | 1.75 (0.64–4.82) |

| …the prognosis with the relatives | 0.58 (0.35–0.96) | 0.93 (0.84–1.04) | 3.08 (1.52–6.26) | 3.09 (1.39–6.88) | 5.22 (2.17–12.6) | 1.68 (0.71–4.02) | 1.59 (0.58–4.35) |

| …the end-of-life care with the patient | 0.71 (0.73–1.18) | 0.89 (0.80–0.98) | 0.67 (0.31–1.43) | 1.49 (0.57–3.89) | 0.70 (0.31–1.56) | 0.38 (0.15–0.93) | 0.43 (0.15–1.19) |

| …the end-of-life care with the relatives | 0.55 (0.33–0.92) | 1.05 (0.93–1.20) | 1.68 (0.75–3.76) | 1.81 (0.69–4.75) | 0.68 (0.31–1.48) | 0.36 (0.14–0.91) | 0.37 (0.12–1.08) |

| The easiest part regarding bad news delivery is to discuss… | |||||||

| …the treatment with the patient | 1.41 (0.90–2.20) | 0.97 (0.87–1.07) | 0.81 (0.44–1.48) | 0.78 (0.39–1.58) | 0.44 (0.21–0.92) | 0.53 (0.21–1.34) | 0.61 (0.21–1.80) |

| …the treatment with the relatives | 1.59 (0.99–2.53) | 1.03 (0.92–1.13) | 1.12 (0.60–2.10) | 1.20 (0.59–2.44) | 0.49 (0.22–1.08) | 0.76 (0.30–1.91) | 0.21 (0.04–0.98) |

About BBN training activities, 385 of 427 (90.2%) students give great value to training with real patients, 317 of 428 (74.1%) with simulated patients, and 291/425 (68.5%) with simulations enacted by themselves. On another side, as classroom activities, 273 of 438 (63.8%) students consider useful case study presented in a written or recorded format, 248 of 428 (57.9%) value equally to attend lectures on the matter, and only 53 of 438 (28.5%) consider virtual sessions as equally valuable. Finally, 376 of 437 (88.1%) students consider feedback at the end of any session as essential. Multivariate models did not signal differences regarding sex, age, or academic level, beyond men being less supportive of feedback sessions and virtual strategies.

DiscussionThe main finding in this study is that medical students, in general, feel unprepared to deliver bad news, something similar to what is found in other parts of the world.10 Even without formal training, medical students believe they are better at BBN as they advance in their training due to their observation of other clinicians and their personal experiences. However, many students would rather have other clinicians deliver the bad news, and we believe it might be due to trust issues and lack of guided practice, which makes it difficult for them to deal with the patients and their family's pain. The results show that as studies progress, especially after beginning clinical activities, students of healthcare areas have less empathic capacities, something previously known,19,20 even starting to develop cynicism as a defense mechanism.21

To develop this skill correctly, the students need to cultivate empathy, as the capacity to comprehend individuals’ emotions and reflect that comprehension.22 It stated that to nurture empathy, it is necessary to develop four different abilities: to discriminate the impact of the news for the patient, to damper the damage perceived, to make the message comprehensible and agreeable, and to have the communicative abilities to do so.23 Although many students report that communication is inherently good for everyone, they agree that the main issue is not about the message's content but its form.24 They also report that women are better at BBN, a cultural element that needs validation and evaluation in later studies. First-year students are frequently more receptive to these courses than their peers at higher levels.25

It is considered that personality structure and coping strategies are crucial aspects of BBN.13 Only a tiny group that considers it unnecessary to get formal training is BBN. Some of the main arguments against training focus on it being an ability that is easily acquired through ‘common sense’, because empathy cannot be taught or because training is not needed to be a good communicator.26 However, experiences worldwide show the opposite: it is possible to improve medical students’ capacity for this matter.10 Additionally, training strategies include different methods, including theoretical and practical courses, virtual or presential, simulations among participants or simulated patients, live practice with students of other healthcare areas, among others.27

Therefore, we propose to create a methodological basis for training as a reflection that begins with experience, is followed by an interpretation process, consolidates when the student brings meaning to it, explores, and compares experiences.28 This method would allow the students to create their perspectives and decide about their behaviors, teaching tools to develop a personal way to deliver the bad news that is positive, efficient, and emotionally aware.29 All of this is proposed in the context of healthcare services that restrict time dedicated to communication, simplify encounters, and do not have ideal privacy conditions, which can impact empathic abilities in the long run.30

This study has some limitations: since participants are volunteers, some students are so unconscious about the topic that they did not even want to get involved, so that the high reception may be overestimated. There should also be noticed lower participation of students in the last courses, which could be due to the higher perception of acquired abilities.

ConclusionVery few students have received formal training regarding this topic, and most of them are interested in training since they see themselves as unprepared. The most challenging topic to discuss is to talk about treatment, prognosis, and passing away, and it is easier to talk with the family than with the patient. Regarding how to be trained, they would like training with real patients, simulated patients, and developing simulations enacted by themselves; they also consider feedback sessions essential.

Considering the existing limitations in role play, it is essential to include the students’ personal experiences in the teaching models that are used, guiding them mainly in the development of their style when delivering bad news.

Multivariate models did not signal differences regarding sex, age, or academic level, beyond men being less supportive of feedback sessions and virtual strategies.

FundingNone declared.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.