Point of care ultrasound study (POCUS) is a relatively new technique in Spanish Emergency Departments (EDs). Nonetheless, its use is increasing, and the number of emergency doctors and the number of papers published in our country has skyrocketed in last decade. Despite this fact, there is still no evidence of how POCUS is taught in our medical schools.

ObjectiveTo ascertain the level of knowledge about POCUS in first year resident doctors of three hospitals in Madrid, and one year after having worked in ED with POCUS practice.

Methods and study designThe study looked at demographic aspects, POCUS knowledge, and opinions about its usefulness in the ED, prior to and after working in ED with routine use of POCUS.

ResultsOf the 265 questionnaires, 197 were first-year residents (Group 1) and 68 second-year residents (Group 2). Another 55 senior medical students completed the questionnaire (Group 3). The majority of Groups 1 and 3 stated to have a very low POCUS level. Almost three-quarters (73%) of Group 2 stated having an intermediate or high level, and 26% even declared having full knowledge. More than half of the students agreed that POCUS was a useful tool in ED.

ConclusionsThere is a low level of knowledge about POCUS among first-year residents. After working in POCUS qualified EDs, these resident doctors state both the importance and their higher level of knowledge of POCUS.

La ecografía a pie de cama (EPC) es una técnica diagnóstica cada día más utilizada por los médicos urgenciólogos en los servicios de urgencias hospitalarios españoles. No obstante, desconocemos el nivel de la EPC de nuestros médicos residentes de primer año (R1).

ObjetivoDeterminar el nivel de conocimientos sobre la EPC de los R1, en 3 hospitales universitarios de Madrid, y el conocimiento un año después de haber trabajado en servicios de urgencias con utilización habitual de la EPC.

MétodosNuestra encuesta investigaba datos demográficos, nivel previo de conocimiento de la EPC y opinión acerca de su utilidad en el servicio de urgencias. También se aplicó la encuesta a 55 estudiantes de medicina del último curso (EM6).

ResultadosDe 265 encuestas: 197 fueron de R1 y 68 de R2. También se pasó la encuesta a otros 55 estudiantes de medicina del último curso (EM6). La mayoría de los R1 y EM6, revelaron un nivel previo muy bajo de conocimientos de la EPC. En cambio, el 73% de los R2, manifestaron un nivel intermedio o alto, e incluso un 26% declararon un conocimiento amplio. Más de la mitad de los encuestados manifestó estar de acuerdo en que la EPC era una herramienta muy útil en el servicio de urgencias.

ConclusionesExiste un bajo nivel de conocimientos sobre la EPC entre los R1. Después de haber trabajado en servicios de urgencias con práctica habitual de EPC, estos mismos médicos residentes, reconocieron tanto la importancia de la EPC como su alto nivel de conocimientos de la EPC.

Point of care ultrasound (POCUS) is a relatively new technique, its use started in some emergency departments (EDs) about thirty years ago.1 Ultrasonography (US) practiced by emergency doctors is an increasingly used technique, and currently of common practice throughout many EDs all over the world. In Spain, since 2008 there is a National Plan of Ultrasound Training for emergency doctors,2 however abdominal US performed by emergency doctors in Spain has been described since 1987.3 In last ten years, many EDs in Spain have reported their experiences with US assessments of patients with abdominal pain,4 suspected deep venous thrombosis5 and most recently, with musculoskeletal complains.6 Also, the first prospective, multicenter study comparing the diagnostic concordance between emergency doctor-performed POCUS vs specialist-performed echo-doppler, in standard clinical practice in the diagnosis of deep venous thrombosis of lower limbs, was published in Spain.7,8

The need to include POCUS into the international medical curricula has been recognized in many studies in industrialized countries.9,10 It had been tested as a pilot experience in second and third-year medical students, demonstrating easy integration into the existing medical school curriculum.11,12

Study justificationDespite the increasing use of POCUS in EDs, we do not have any evidence of how POCUS is taught in our medical schools, regardless if taught along with other subjects, or as a single subject. Given the increasing importance of POCUS in the standard clinical practice in the ED, it will be useful to know the POCUS background of our new resident doctors. After these data collection, we will try to investigate the influence of this POCUS-ED environment in these same doctors.

ObjectiveTo ascertain the level of knowledge about POCUS: (1) in first-year resident doctors of three hospitals in Madrid; (2) in second-year resident doctors, after having worked in an ED with common use of POCUS.

Methods and study designSurveyWe included three topics in our survey, besides demographic aspects of the participants: (1) self-assessment of POCUS knowledge and teaching in undergraduate courses, (2) personal opinion about usefulness of POCUS, prior and after working in an ED with common use of POCUS, (3) interest about POCUS in future ED courses. The investigators previously agreed the topics and statements of the survey. All the investigators had a broad teaching experience with resident doctors.

All the questions could be answered either as affirmative or negative (dichotomous variable), or as an ordinal Likert's scale. In total, twenty-one questions were included. Three validation tests were performed to all the questions: comprehension, tendentiousness and reproducibility of the results. The whole survey is shown in Annex 1 (in English), and Annex 2 (original in Spanish). For the validation, this survey was given to senior medical students of a Spanish speaking university (Peruvian University “Cayetano Heredia”). Both, the comprehension and tendentiousness tests were considered as positive, if the agreement among observers reached 90% concordance. The reproducibility test was reached when the results of two surveys, fulfilled by the same individual but in different times, reached 100% concordance in a dichotomous variable questions, and an 80% concordance in the questions with ordinal answers (Table 1).

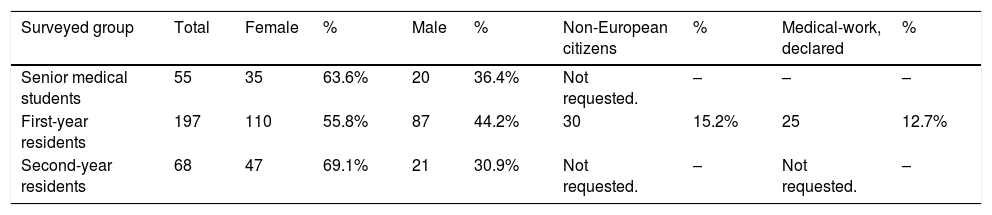

Demographic features of our population.

| Surveyed group | Total | Female | % | Male | % | Non-European citizens | % | Medical-work, declared | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Senior medical students | 55 | 35 | 63.6% | 20 | 36.4% | Not requested. | – | – | – |

| First-year residents | 197 | 110 | 55.8% | 87 | 44.2% | 30 | 15.2% | 25 | 12.7% |

| Second-year residents | 68 | 47 | 69.1% | 21 | 30.9% | Not requested. | – | Not requested. | – |

The surveys were sent to 345 individuals: first-year resident doctors, who started their medical training in 2017, in the following hospitals: University Hospital “Fundación Jiménez Díaz” (FJD), University Hospital “La Paz” (HULP) and University Hospital “Ramón y Cajal” (HRYC). The surveys were also sent to second year resident doctors of the same hospitals (all of them working in ED with access to POCUS).

The surveys were sent by e-mail or by Quick Response® (QR code) via e-mail, during the hospital's induction/teaching meetings for new resident doctors. In every case, the investigators started explaining the purpose of the study, requested permission, and distributed the survey.

The participation in this survey was voluntary and anonymous. The control of double response was performed through double-checking of repeated demographic data and Internet Protocol (TCP/IP).

MethodBesides first-year resident doctors, the survey was also sent to 55 senior medical student volunteers and to 68 second-year medical residents using the same methodology. All the second-year residents had worked previously in an ED with POCUS during their first-year training. The last group was included to assess their opinion about POCUS after having worked with this technique in the ED for one year.

Statistical analysisA descriptive statistics was used to characterize the residents who participated in this study and to identify the distribution of the variables. Frequency measures, Fisher's exact test and Chi-squared test were employed accordingly.

All data were processed with the statistic software Stata V.12 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA).

Ethical aspectsConfidentialityThis survey was completely anonymous and the participants could not be identified. However to reduce the possibility of answering the survey twice we included a field to complete the five last characters of the identification card and TCIP/IP code of the device where the survey was completed.

Informed consentAs no patients were involved, there was no need for informed consent from any patient. Furthermore, every participant did so voluntarily witch was confirmed by completion of the electronic form.

ResultsTwo hundred and sixty five surveys were collected from the resident doctors: 197 from first-year residents and 68 from second-year residents. In addition, 55 senior medical students answered the survey. The response rate was 76%.

Demographic dataSixty five percent of the sample was female. The median of age was 26 (range 24–33). Considering only first year resident doctors, 14.2% came from non-European Union (nEU) countries, and all of them except two, were from Latin-America. Previous medical work was declared by 12%, all of these were from Latin-American countries.

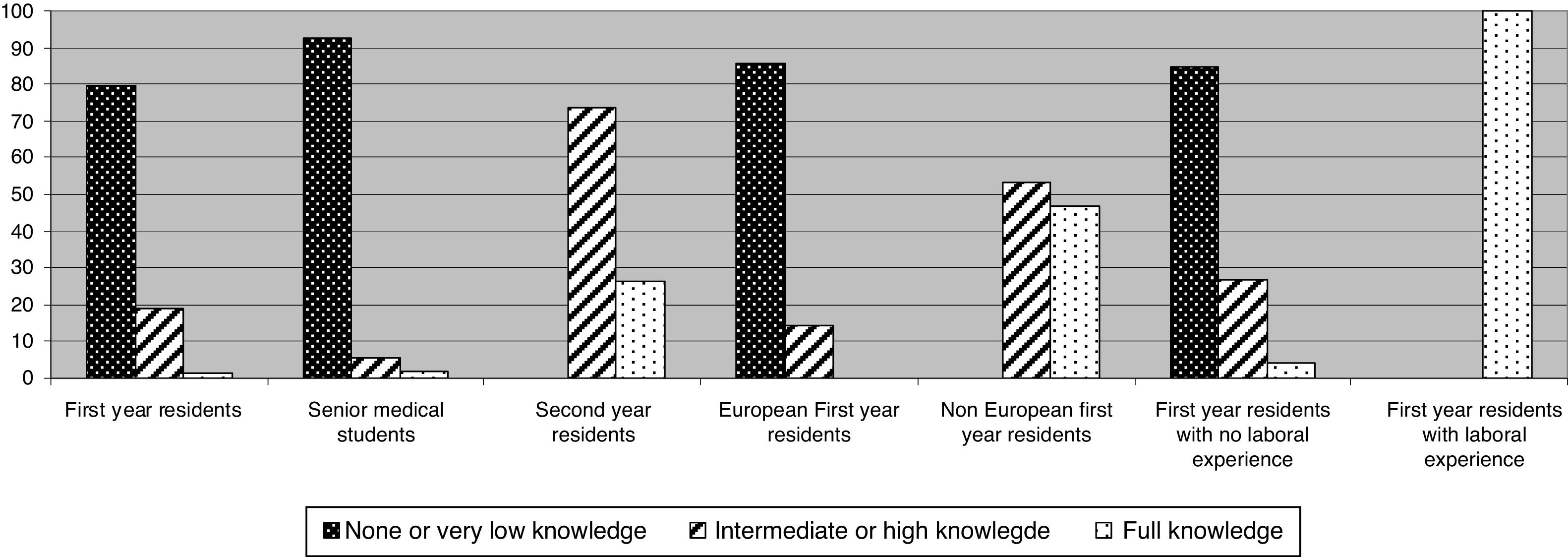

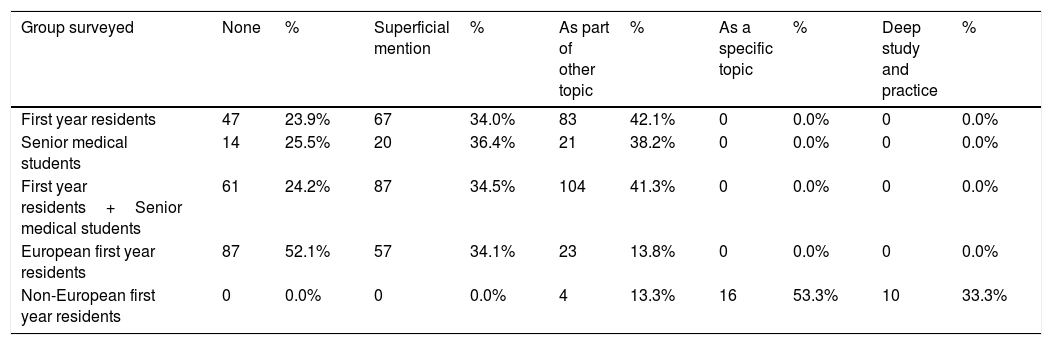

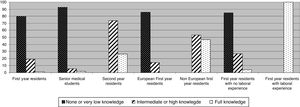

Previous knowledge about POCUS and its usefulnessAlmost 80% of first year residents and 92.7% of senior medical students stated no knowledge or a very low knowledge about POCUS. None of the second-year residents declared no or very low knowledge; on the contrary, 73.6% of them stated an intermediate or high level of knowledge about POCUS and 26.5% declared full knowledge. Considering only residents from nEU countries, intermediate and high knowledge was stated in 53.4% of surveys, and full knowledge in 46.7%. All residents who had previous medical experience answered full knowledge of POCUS and its usefulness (Fig. 1).

Level of knowledge about POCUS and its usefulness.

Proportion differences between first-year and second-year residents and between senior medical students and second-year residents were statistically significant (P<0.001).

Proportion differences between European and non-European residents were statistically significant (P<0.001).

No statistical comparison could be made between residents with or without previous work experience due to the distribution of proportions.

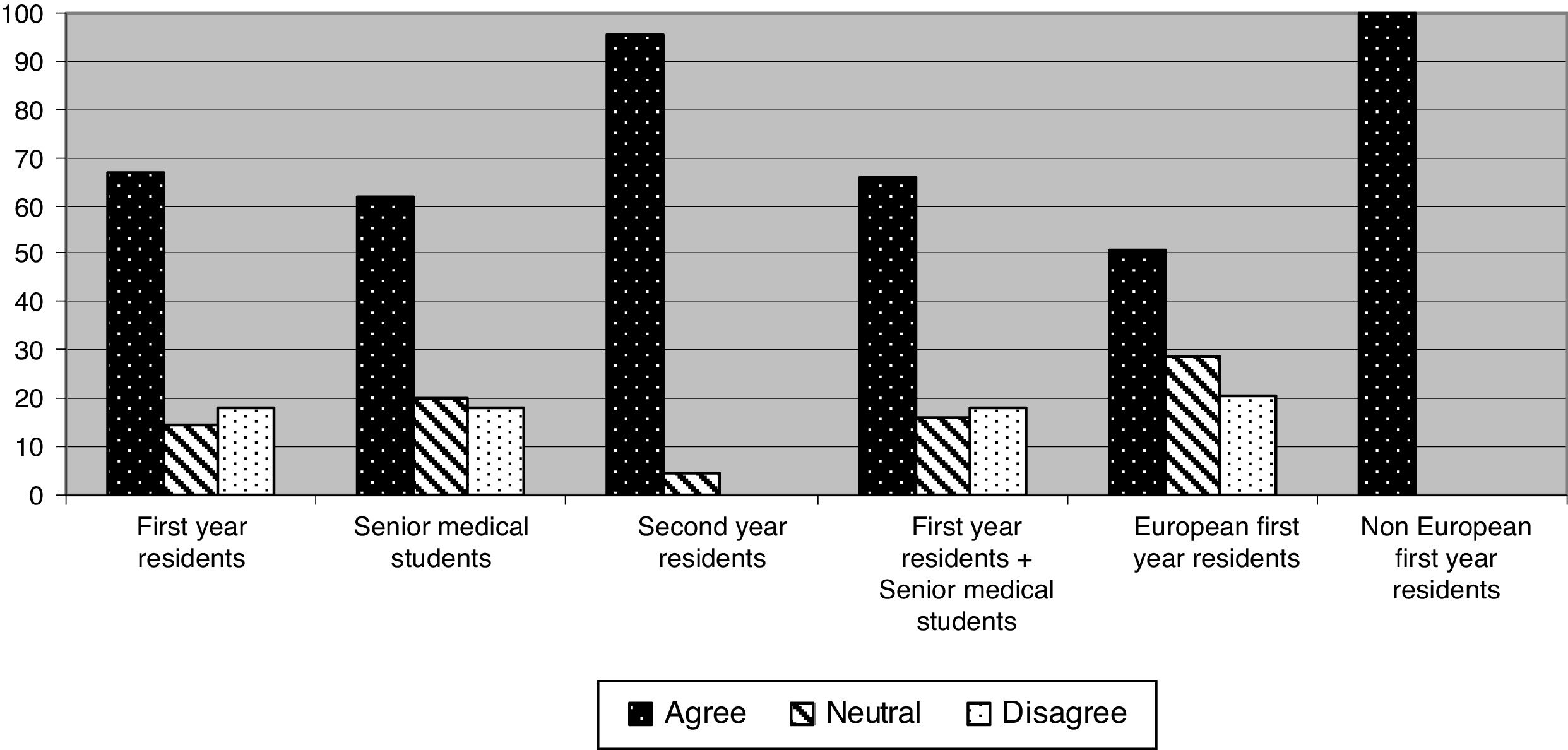

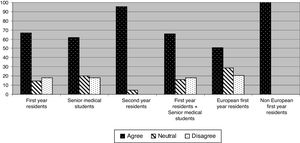

More than 50% of the participants agreed that POCUS was a useful tool in the ED. The highest agreement was among nEU medical residents (100%) and second-year residents (95.6%). On the contrary, the poorest agreement was found in first-year residents (67%) and senior medical students (61.8%). The difference of agreement between first and second-year residents, as well as between EU and nEU residents, were statistically significant (P<0.001) (Fig. 2).

Extent of agreement with the statement: POCUS is a useful tool for patient assessment in the emergency department.

Proportion of agreement between second-year residents vs. senior medical students; and first-year residents vs. the sum of both were statistically significant (P<0.001). Proportion of agreement of European and non-European first-year residents was also statistically significant (P<0.001).

Among first-year residents, 23.9% answered that POCUS was never taught directly or as part of another subject during their medical training. In this same group, 34% answered they were given only superficial teaching about POCUS and 42.1% answered that POCUS was included as part of another subject. Nobody from the first-year resident nor from the senior medical student group answered that POCUS was taught in depth as a specific subject. However, 53.3% of nEU resident doctors answered that POCUS was a specific subject in their curricula, and 33.3% answered that it was a subject studied in depth (Table 2).

Level of contribution of medical school in the knowledge and skills on POCUS. Due to distribution of proportions in European and non-European first year residents, most comparisons could not be assessed by statistics tests. The teaching of POCUS as a subject included as part of other main subject, was not statistically different between European and non-European residents.

| Group surveyed | None | % | Superficial mention | % | As part of other topic | % | As a specific topic | % | Deep study and practice | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First year residents | 47 | 23.9% | 67 | 34.0% | 83 | 42.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Senior medical students | 14 | 25.5% | 20 | 36.4% | 21 | 38.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| First year residents+Senior medical students | 61 | 24.2% | 87 | 34.5% | 104 | 41.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| European first year residents | 87 | 52.1% | 57 | 34.1% | 23 | 13.8% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Non-European first year residents | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 4 | 13.3% | 16 | 53.3% | 10 | 33.3% |

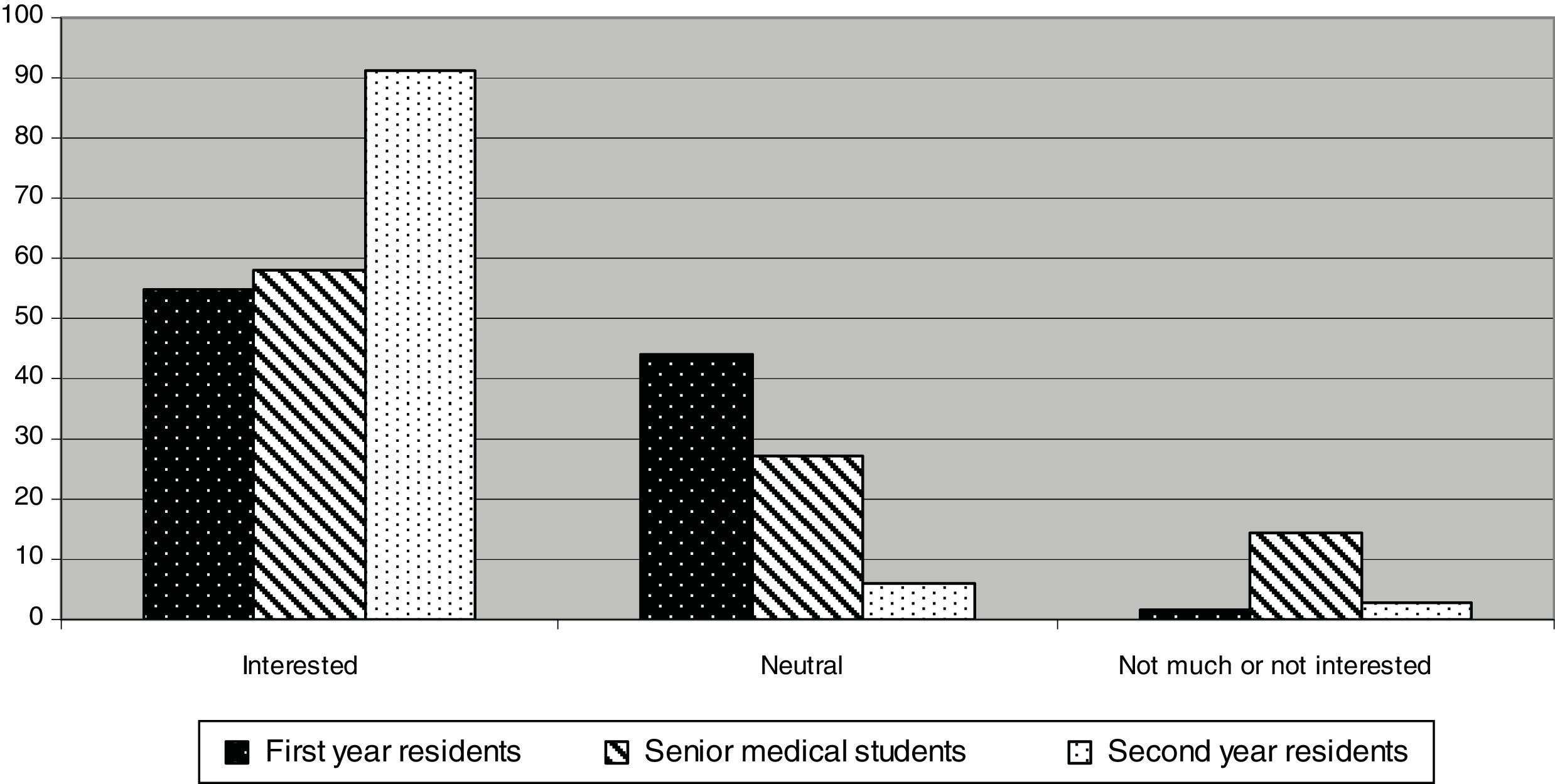

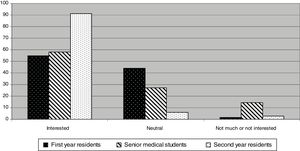

The proportion of subjects who answered to be interested in POCUS training was 54.8% among first-year residents, 58.2% among senior medical students and 91.2% among second-year residents (P<0.001 when comparing both first proportion with the last one). From the senior medical students group, 14.6% of them stated not to be very interested or not interested at all in POCUS training. This proportion was significantly higher than the 1.5% of first-year residents and the 3% of second-year residents (P<0.001 in both cases) (Fig. 3).

DiscussionAs stated above, we cannot compare our results with previous ones, because this study is pioneering, nonetheless, we can make a reasonable interpretation about those data, taking into account our teaching and working environment.

As we could suspect, at least in Spain, undergraduate POCUS teaching is negligible (80% of first year residents and 92% of senior medical students rated as nil or poor). However, after having worked in a POCUS environment, none of the second-year residents declared none or a very low POCUS knowledge.

Regarding the usefulness of POCUS in the ED, the poorest level of agreement was found in first-year residents (67%) and senior medical students (61.8%); in contrast, the highest agreement was among nEU medical residents (100%) and second-year residents (95.6%). The impression is that nEU doctors start with some advantage over EU doctors (including Spain).

A good answer to the above results is found when almost 24% of these first-year residents, answered that POCUS was never taught during their medical training, 34% were given only a quick teaching about POCUS and 42% had POCUS included as part of other subject.

Regarding to the interest in POCUS training, 54% among first-year residents, 58% among senior medical students and 91% second-year residents showed this interest. Again, it seems like after working in POCUS qualified EDs, these resident doctors realize both the importance of POCUS and their willingness to learn the technique.

We honestly believe that with proper induction, POCUS will sow the seed and many more emergency doctors will be mastering POCUS in the next few years in that environment. In addition, the hospital directors should be aware of this information, bearing in mind the usefulness of POCUS in EDs and the willingness of resident doctors to learn this technique, for faster and eventually better care of the ED patient.

ConclusionsThere is a general lack of knowledge about POCUS among first-year residents and senior medical students, probably because they did not get any teaching in their undergraduate training.

After working in POCUS qualified EDs, these first-year resident doctors realize both the importance of POCUS and their willingness of learning this technique.

Conflict of interestNone of the authors nor contributing authors, researchers and collaborators, nor their families have received any benefits nor economic compensation from the completion of this study.

The authors are indebted to Dr. César Carballo Cardona, chief of the Emergency Department at Hospital Universitario La Paz. Dr. Joaquín García Cañete and Dr. Antonio Blanco, chiefs of the Emergency Department at Hospital Universitario Fundación Jiménez Diaz. Dr. Joseph Hogg, partner at Abbey House Medical Centre, for his careful English revision.